7.2

Hemoglobin Binds Oxygen Cooperatively

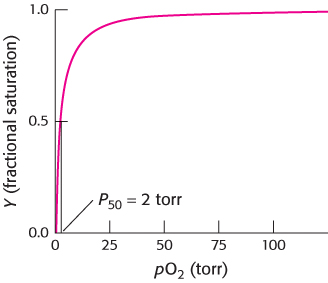

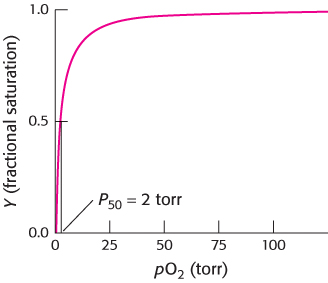

We can determine the oxygen-binding properties of each of these proteins by observing its oxygen-binding curve, a plot of the fractional saturation versus the concentration of oxygen. The fractional saturation, Y, is defined as the fraction of possible binding sites that contain bound oxygen. The value of Y can range from 0 (all sites empty) to 1 (all sites filled). The concentration of oxygen is most conveniently measured by its partial pressure, pO2. For myoglobin, a binding curve indicating a simple chemical equilibrium is observed (Figure 7.7). Notice that the curve rises sharply as pO2 increases and then levels off. Half-saturation of the binding sites, referred to as P50 (for 50% saturated), is at the relatively low value of 2 torr (mm Hg), indicating that oxygen binds with high affinity to myoglobin.

FIGURE 7.7Oxygen binding by myoglobin. Half the myoglobin molecules have bound oxygen when the oxygen partial pressure is 2 torr.

Torr

A unit of pressure equal to that exerted by a column of mercury 1 mm high at 0°C and standard gravity (1 mm Hg). Named after Evangelista Torricelli (1608–1647), inventor of the mercury barometer.

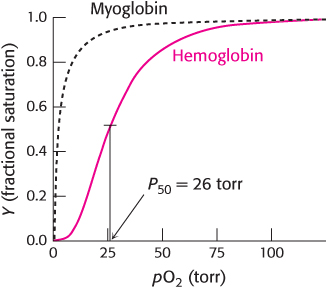

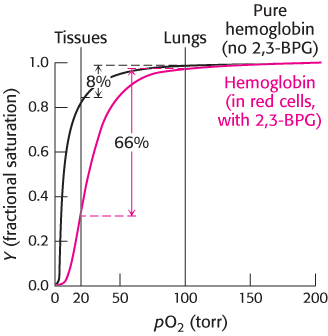

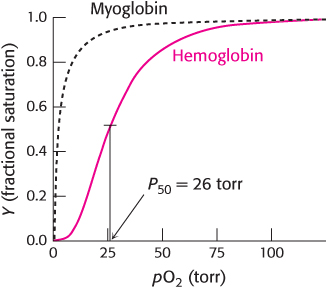

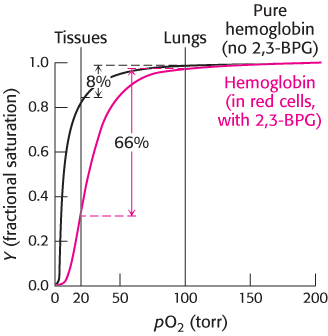

In contrast, the oxygen-binding curve for hemoglobin in red blood cells shows some remarkable features (Figure 7.8). It does not look like a simple binding curve such as that for myoglobin; instead, it resembles an “S.” Such curves are referred to as sigmoid because of their S-like shape. In addition, oxygen binding for hemoglobin (P50 = 26 torr) is significantly weaker than that for myoglobin. Note that this binding curve is derived from hemoglobin in red blood cells.

FIGURE 7.8Oxygen binding by hemoglobin. This curve, obtained for hemoglobin in red blood cells, is shaped somewhat like an “S,” indicating that distinct, but interacting, oxygen-binding sites are present in each hemoglobin molecule. Half-saturation for hemoglobin is 26 torr. For comparison, the binding curve for myoglobin is shown as a dashed black curve.

A sigmoid binding curve indicates that a protein exhibits a special binding behavior. For hemoglobin, this shape suggests that the binding of oxygen at one site within the hemoglobin tetramer increases the likelihood that oxygen binds at the remaining unoccupied sites. Conversely, the unloading of oxygen at one heme facilitates the unloading of oxygen at the others. This sort of binding behavior is referred to as cooperative, because the binding reactions at individual sites in each hemoglobin molecule are not independent of one another. We will return to the mechanism of this cooperativity shortly.

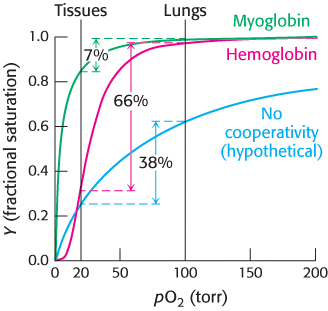

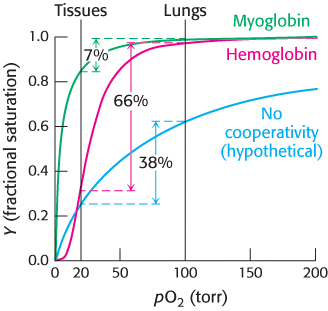

What is the physiological significance of the cooperative binding of oxygen by hemoglobin? Oxygen must be transported in the blood from the lungs, where the partial pressure of oxygen is relatively high (approximately 100 torr), to the actively metabolizing tissues, where the partial pressure of oxygen is much lower (typically, 20 torr). Let us consider how the cooperative behavior indicated by the sigmoid curve leads to efficient oxygen transport (Figure 7.9). In the lungs, hemoglobin becomes nearly saturated with oxygen such that 98% of the oxygen-binding sites are occupied. When hemoglobin moves to the tissues and releases O2, the saturation level drops to 32%. Thus, a total of 98 −32 = 66% of the potential oxygen-binding sites contribute to oxygen transport. The cooperative release of oxygen favors a more-complete unloading of oxygen in the tissues. If myoglobin were employed for oxygen transport, it would be 98% saturated in the lungs, but would remain 91% saturated in the tissues, and so only 98 −91 = 7% of the sites would contribute to oxygen transport; myoglobin binds oxygen too tightly to be useful in oxygen transport. Nature might have solved this problem by weakening the affinity of myoglobin for oxygen to maximize the difference in saturation between 20 and 100 torr. However, for such a protein, the most oxygen that could be transported from a region in which pO2 is 100 torr to one in which it is 20 torr is 63 −25 = 38%, as indicated by the blue curve in Figure 7.9. Thus, the cooperative binding and release of oxygen by hemoglobin enables it to deliver nearly 10 times as much oxygen as could be delivered by myoglobin and more than 1.7 times as much as could be delivered by any noncooperative protein.

FIGURE 7.9Cooperativity enhances oxygen delivery by hemoglobin. Because of cooperativity between O2 binding sites, hemoglobin delivers more O2 to actively metabolizing tissues than would myoglobin or any noncooperative protein, even one with optimal O2 affinity.

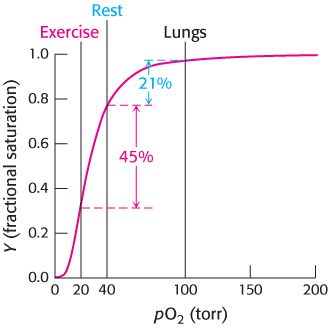

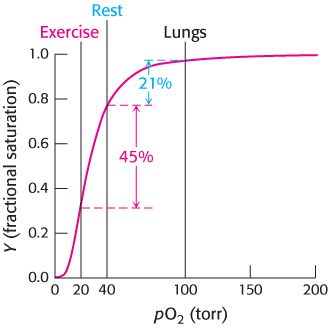

Closer examination of oxygen concentrations in tissues at rest and during exercise underscores the effectiveness of hemoglobin as an oxygen carrier (Figure 7.10). Under resting conditions, the oxygen concentration in muscle is approximately 40 torr, but during exercise the concentration is reduced to 20 torr. In the decrease from 100 torr in the lungs to 40 torr in resting muscle, the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin is reduced from 98% to 77%, and so 98 −77 = 21% of the oxygen is released over a drop of 60 torr. In a decrease from 40 torr to 20 torr, the oxygen saturation is reduced from 77% to 32%, corresponding to an oxygen release of 45% over a drop of 20 torr. Thus, because the change in oxygen concentration from rest to exercise corresponds to the steepest part of the oxygen-binding curve, oxygen is effectively delivered to tissues where it is most needed. In Section 7.3, we shall examine other properties of hemoglobin that enhance its physiological responsiveness.

FIGURE 7.10Responding to exercise. The drop in oxygen concentration from 40 torr in resting tissues to 20 torr in exercising tissues corresponds to the steepest part of the observed oxygen-binding curve. As shown here, hemoglobin is very effective in providing oxygen to exercising tissues.

Oxygen binding markedly changes the quaternary structure of hemoglobin

The cooperative binding of oxygen by hemoglobin requires that the binding of oxygen at one site in the hemoglobin tetramer influence the oxygen-binding properties at the other sites. Given the large separation between the iron sites, direct interactions are not possible. Thus, indirect mechanisms for coupling the sites must be at work. These mechanisms are intimately related to the quaternary structure of hemoglobin.

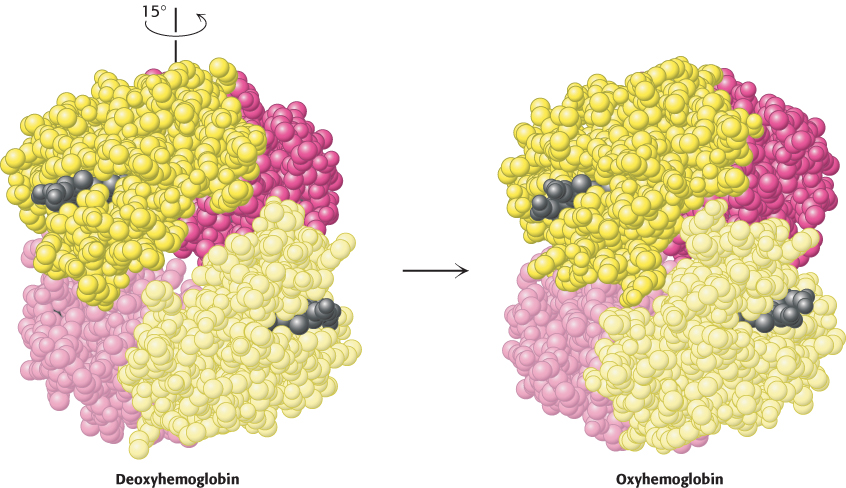

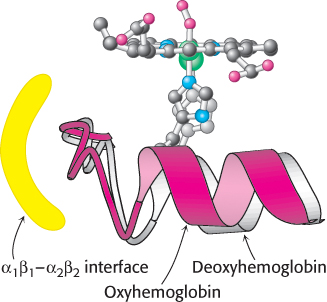

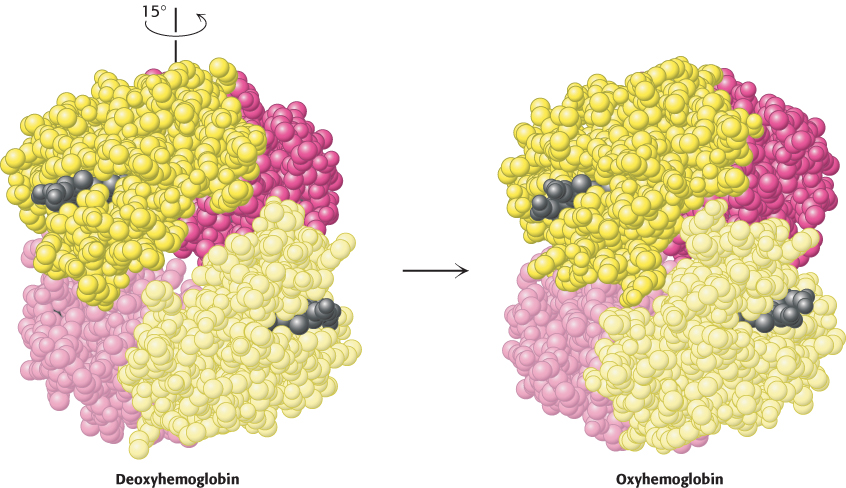

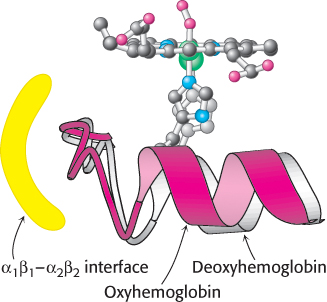

Hemoglobin undergoes substantial changes in quaternary structure on oxygen binding: the α1β1 and α2β2 dimers rotate approximately 15 degrees with respect to one another (Figure 7.11). The dimers themselves are relatively unchanged, although there are localized conformational shifts. Thus, the interface between the α1β1 and α2β2 dimers is most affected by this structural transition. In particular, the α1β1 and α2β2 dimers are freer to move with respect to one another in the oxygenated state than they are in the deoxygenated state.

FIGURE 7.11 Quaternary structural changes on oxygen binding by hemoglobin. Notice that, on oxygenation, one αβ dimer shifts with respect to the other by a rotation of 15 degrees.

FIGURE 7.11 Quaternary structural changes on oxygen binding by hemoglobin. Notice that, on oxygenation, one αβ dimer shifts with respect to the other by a rotation of 15 degrees.

[Drawn from 1A3N.pdb and 1LFQ.pdb.]

The quaternary structure observed in the deoxy form of hemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, is often referred to as the T (for tense) state because it is quite constrained by subunit–subunit interactions. The quaternary structure of the fully oxygenated form, oxyhemoglobin, is referred to as the R (for relaxed) state. In light of the observation that the R form of hemoglobin is less constrained, the tense and relaxed designations seem particularly apt. Importantly, in the R state, the oxygen-binding sites are free of strain and are capable of binding oxygen with higher affinity than are the sites in the T state. By triggering the shift of the hemoglobin tetramer from the T state to the R state, the binding of oxygen to one site increases the binding affinity of other sites.

Hemoglobin cooperativity can be potentially explained by several models

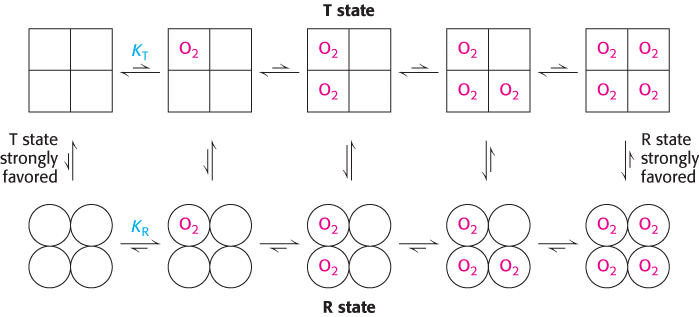

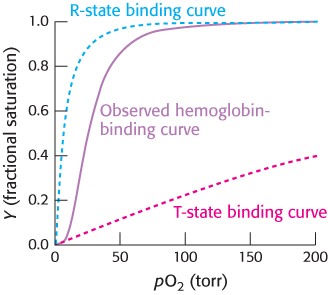

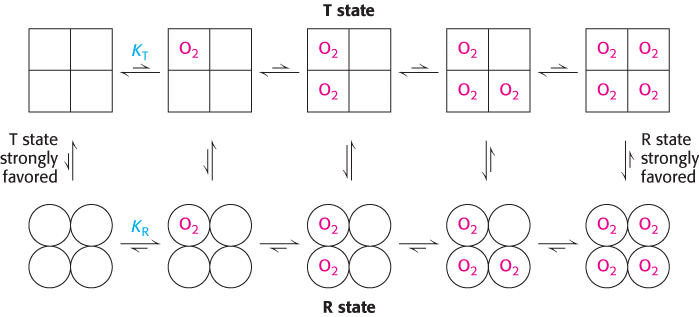

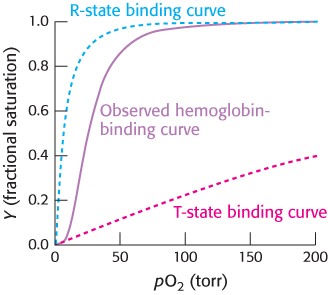

Two limiting models have been developed to explain the cooperative binding of ligands to a multisubunit assembly such as hemoglobin. In the concerted model, also known as the MWC model after Jacques Monod, Jeffries Wyman, and Jean-Pierre Changeux, who first proposed it, the overall assembly can exist only in two forms: the T state and the R state. The binding of ligands simply shifts the equilibrium between these two states (Figure 7.12). Thus, as a hemoglobin tetramer binds each oxygen molecule, the probability that the tetramer is in the R state increases. Deoxyhemoglobin tetramers are almost exclusively in the T state. However, the binding of oxygen to one site in the molecule shifts the equilibrium toward the R state. If a molecule assumes the R quaternary structure, the oxygen affinity of its sites increases. Additional oxygen molecules are now more likely to bind to the three unoccupied sites. Thus, the binding curve for hemoglobin can be seen as a combination of the binding curves that would be observed if all molecules remained in the T state or if all of the molecules were in the R state. As oxygen molecules bind, the hemoglobin tetramers convert from the T state into the R state, yielding the sigmoid binding curve so important for efficient oxygen transport (Figure 7.13).

FIGURE 7.12Concerted model. All molecules exist either in the T state or in the R state. At each level of oxygen loading, an equilibrium exists between the T and R states. The equilibrium shifts from strongly favoring the T state with no oxygen bound to strongly favoring the R state when the molecule is fully loaded with oxygen. The R state has a greater affinity for oxygen than does the T state.

FIGURE 7.13T-to-R transition. The binding curve for hemoglobin can be seen as a combination of the binding curves that would be observed if all molecules remained in the T state or if all of the molecules were in the R state. The sigmoidal curve is observed because molecules convert from the T state into the R state as oxygen molecules bind.

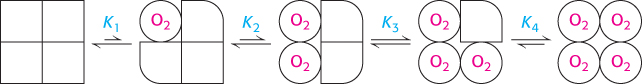

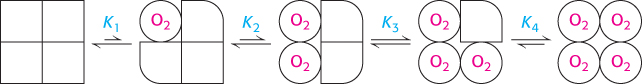

In the concerted model, each tetramer can exist in only two states, the T state and the R state. In an alternative model, the sequential model, the binding of a ligand to one site in an assembly increases the binding affinity of neighboring sites without inducing a full conversion from the T into the R state (Figure 7.14).

FIGURE 7.14Sequential model. The binding of a ligand changes the conformation of the subunit to which it binds. This conformational change induces changes in neighboring subunits that increase their affinity for the ligand.

Is the cooperative binding of oxygen by hemoglobin better described by the concerted or the sequential model? Neither model in its pure form fully accounts for the behavior of hemoglobin. Instead, a combined model is required. Hemoglobin behavior is concerted in that the tetramer with three sites occupied by oxygen is almost always in the quaternary structure associated with the R state. The remaining open binding site has an affinity for oxygen more than 20-fold greater than that of fully deoxygenated hemoglobin binding its first oxygen. However, the behavior is not fully concerted, because hemoglobin with oxygen bound to only one of four sites remains primarily in the T-state quaternary structure. Yet, this molecule binds oxygen three times as strongly as does fully deoxygenated hemoglobin, an observation consistent only with a sequential model. These results highlight the fact that the concerted and sequential models represent idealized limiting cases, which real systems may approach but rarely attain.

Structural changes at the heme groups are transmitted to the α1β1−α2β2 interface

We now examine how oxygen binding at one site is able to shift the equilibrium between the T and R states of the entire hemoglobin tetramer. As in myoglobin, oxygen binding causes each iron atom in hemoglobin to move from outside the plane of the porphyrin into the plane. When the iron atom moves, the proximal histidine residue moves with it. This histidine residue is part of an α helix, which also moves (Figure 7.15). The carboxyl terminal end of this α helix lies in the interface between the two αβ dimers. The change in position of the carboxyl terminal end of the helix favors the T-to-R transition. Consequently, the structural transition at the iron ion in one subunit is directly transmitted to the other subunits. The rearrangement of the dimer interface provides a pathway for communication between subunits, enabling the cooperative binding of oxygen.

FIGURE 7.15Conformational changes in hemoglobin. The movement of the iron ion on oxygenation brings the iron-associated histidine residue toward the porphyrin ring. The associated movement of the histidine-containing α helix alters the interface between the αβ dimers, instigating other structural changes. For comparison, the deoxyhemoglobin structure is shown in gray behind the oxyhemoglobin structure in red.

2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate in red cells is crucial in determining the oxygen affinity of hemoglobin

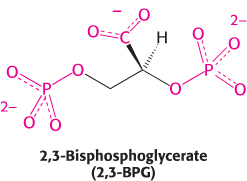

For hemoglobin to function efficiently, the T state must remain stable until the binding of sufficient oxygen has converted it into the R state. In fact, however, the T state of hemoglobin is highly unstable, pushing the equilibrium so far toward the R state that little oxygen would be released in physiological conditions. Thus, an additional mechanism is needed to properly stabilize the T state. This mechanism was discovered by comparing the oxygen-binding properties of hemoglobin in red blood cells with fully purified hemoglobin (Figure 7.16). Pure hemoglobin binds oxygen much more tightly than does hemoglobin in red blood cells. This dramatic difference is due to the presence within these cells of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG; also known as 2,3-diphosphoglycerate or 2,3-DPG).

FIGURE 7.16Oxygen binding by pure hemoglobin compared with hemoglobin in red blood cells. Pure hemoglobin binds oxygen more tightly than does hemoglobin in red blood cells. This difference is due to the presence of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) in red blood cells.

This highly anionic compound is present in red blood cells at approximately the same concentration as that of hemoglobin (∼ 2 mM). Without 2,3-BPG, hemoglobin would be an extremely inefficient oxygen transporter, releasing only 8% of its cargo in the tissues.

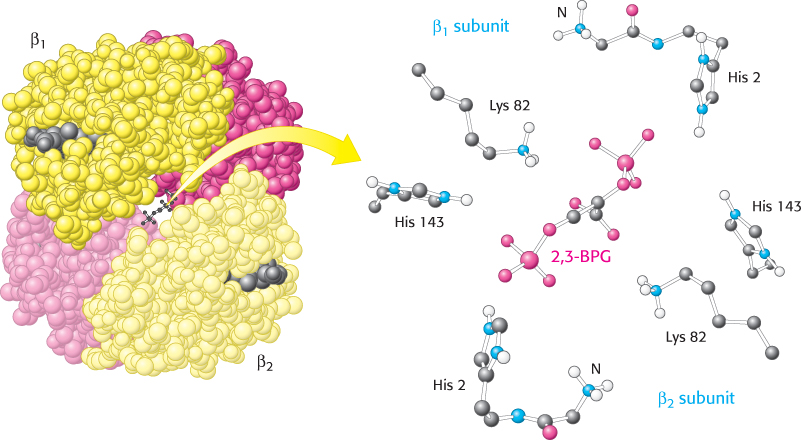

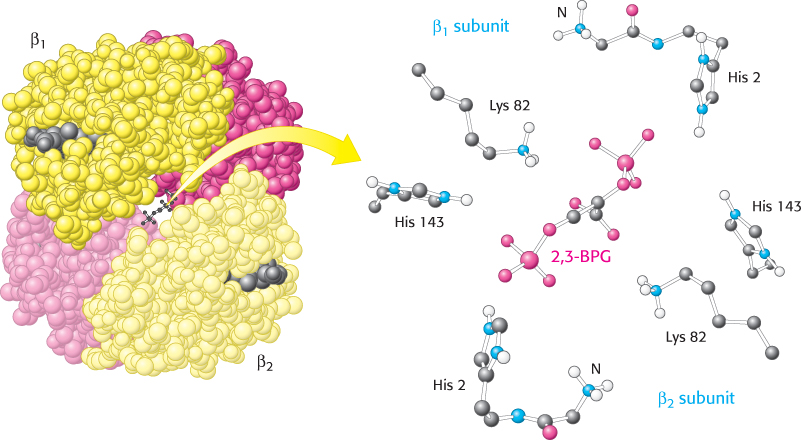

How does 2,3-BPG lower the oxygen affinity of hemoglobin so significantly? Examination of the crystal structure of deoxyhemoglobin in the presence of 2,3-BPG reveals that a single molecule of 2,3-BPG binds in the center of the tetramer, in a pocket present only in the T form (Figure 7.17). On T-to-R transition, this pocket collapses and 2,3-BPG is released. Thus, in order for the structural transition from T to R to take place, the bonds between hemoglobin and 2,3-BPG must be broken. In the presence of 2,3-BPG, more oxygen-binding sites within the hemoglobin tetramer must be occupied in order to induce the T-to-R transition, and so hemoglobin remains in the lower-affinity T state until higher oxygen concentrations are reached. This mechanism of regulation is remarkable because 2,3-BPG does not in any way resemble oxygen, the molecule on which hemoglobin carries out its primary function. 2,3-BPG is referred to as an allosteric effector (from the Greek allos, “other,” and stereos, “structure”). Regulation by a molecule structurally unrelated to oxygen is possible because the allosteric effector binds to a site that is completely distinct from that for oxygen. We will encounter allosteric effects again when we consider enzyme regulation in Chapter 10.

FIGURE 7.17 Mode of binding of 2,3-BPG to human deoxyhemoglobin. 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate binds to the central cavity of deoxyhemoglobin (left). There, it interacts with three positively charged groups on each β chain (right).

FIGURE 7.17 Mode of binding of 2,3-BPG to human deoxyhemoglobin. 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate binds to the central cavity of deoxyhemoglobin (left). There, it interacts with three positively charged groups on each β chain (right).

[Drawn from 1B86.pdb.]

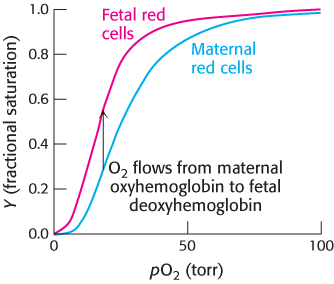

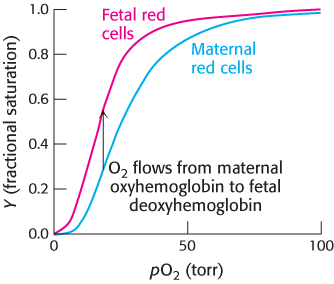

FIGURE 7.18Oxygen affinity of fetal red blood cells. Fetal red blood cells have a higher oxygen affinity than do maternal red blood cells because fetal hemoglobin does not bind 2,3-BPG as well as maternal hemoglobin does.

The binding of 2,3-BPG to hemoglobin has other crucial physiological consequences. The globin gene expressed by human fetuses differs from that expressed by adults; fetal hemoglobin tetramers include two α chains and two γ chains. The γ chain, a result of gene duplication, is 72% identical in amino acid sequence with the β chain. One noteworthy change is the substitution of a serine residue for His 143 in the β chain, part of the 2,3-BPG-binding site. This change removes two positive charges from the 2,3-BPG-binding site (one from each chain) and reduces the affinity of 2,3-BPG for fetal hemoglobin. Consequently, the oxygen-binding affinity of fetal hemoglobin is higher than that of maternal (adult) hemoglobin (Figure 7.18). This difference in oxygen affinity allows oxygen to be effectively transferred from maternal to fetal red blood cells. We have here an example in which gene duplication and specialization produced a ready solution to a biological challenge—in this case, the transport of oxygen from mother to fetus.

The binding of 2,3-BPG to hemoglobin has other crucial physiological consequences. The globin gene expressed by human fetuses differs from that expressed by adults; fetal hemoglobin tetramers include two α chains and two γ chains. The γ chain, a result of gene duplication, is 72% identical in amino acid sequence with the β chain. One noteworthy change is the substitution of a serine residue for His 143 in the β chain, part of the 2,3-BPG-binding site. This change removes two positive charges from the 2,3-BPG-binding site (one from each chain) and reduces the affinity of 2,3-BPG for fetal hemoglobin. Consequently, the oxygen-binding affinity of fetal hemoglobin is higher than that of maternal (adult) hemoglobin (Figure 7.18). This difference in oxygen affinity allows oxygen to be effectively transferred from maternal to fetal red blood cells. We have here an example in which gene duplication and specialization produced a ready solution to a biological challenge—in this case, the transport of oxygen from mother to fetus.

Carbon monoxide can disrupt oxygen transport by hemoglobin

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas that binds to hemoglobin at the same site as oxygen, forming a complex termed carboxyhemoglobin. Formation of carboxyhemoglobin exerts devastating effects on normal oxygen transport in two ways. First, carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin about 200-fold more tightly than does oxygen. Even at low partial pressures in the blood, carbon monoxide will displace oxygen from hemoglobin, preventing its delivery. Second, carbon monoxide bound to one site in hemoglobin will shift the oxygen saturation curve of the remaining sites to the left, forcing the tetramer into the R state. This results in an increased affinity for oxygen, preventing its dissociation at tissues.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas that binds to hemoglobin at the same site as oxygen, forming a complex termed carboxyhemoglobin. Formation of carboxyhemoglobin exerts devastating effects on normal oxygen transport in two ways. First, carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin about 200-fold more tightly than does oxygen. Even at low partial pressures in the blood, carbon monoxide will displace oxygen from hemoglobin, preventing its delivery. Second, carbon monoxide bound to one site in hemoglobin will shift the oxygen saturation curve of the remaining sites to the left, forcing the tetramer into the R state. This results in an increased affinity for oxygen, preventing its dissociation at tissues.

Exposure to carbon monoxide—from gas appliances and running automobiles, for example—can cause carbon monoxide poisoning, in which patients exhibit nausea, vomiting, lethargy, weakness, and disorientation. One treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning is administration of 100% oxygen, often at pressures greater than atmospheric pressure (this treatment is referred to as hyperbaric oxygen therapy). With this therapy, the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood becomes sufficiently high to increase substantially the displacement of carbon monoxide from hemoglobin. Exposure to high concentrations of carbon monoxide, however, can be rapidly fatal: in the United States, about 2,500 people die each year from carbon monoxide poisoning, about 500 of them from accidental exposures and nearly 2,000 by suicide.

FIGURE 7.11 Quaternary structural changes on oxygen binding by hemoglobin. Notice that, on oxygenation, one αβ dimer shifts with respect to the other by a rotation of 15 degrees.

FIGURE 7.11 Quaternary structural changes on oxygen binding by hemoglobin. Notice that, on oxygenation, one αβ dimer shifts with respect to the other by a rotation of 15 degrees.

FIGURE 7.17 Mode of binding of 2,3-

FIGURE 7.17 Mode of binding of 2,3-

The binding of 2,3-

The binding of 2,3- Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas that binds to hemoglobin at the same site as oxygen, forming a complex termed carboxyhemoglobin. Formation of carboxyhemoglobin exerts devastating effects on normal oxygen transport in two ways. First, carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin about 200-

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas that binds to hemoglobin at the same site as oxygen, forming a complex termed carboxyhemoglobin. Formation of carboxyhemoglobin exerts devastating effects on normal oxygen transport in two ways. First, carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin about 200-