1.2 The Life-Span Perspective

The life-span perspective (Fingerman et al., 2011; Lerner, 2010) takes into account all phases of life, not just the first two decades, which were once the sole focus of developmental study. By including the entire life (see TABLE 1.1), this perspective leads to a new understanding of human development as multidirectional, multicontextual, multicultural, multidisciplinary, and plastic (Baltes et al., 2006; Staudinger & Lindenberger, 2003). Ages are only a rough guide to “change over time.”

| Infancy | 0 to 2 years |

| Early childhood | 2 to 6 years |

| Middle childhood | 6 to 11 years |

| Adolescence | 11 to 18 years |

| Emerging Adulthood | 18 to 25 years |

| Adulthood | 25 to 65 years |

| Late adulthood | 65 years and older |

| As you will learn, developmentalists are reluctant to specify chronological ages for any period of development, since time is only one of many variables that affect each person. However, age is a crucial variable, and development can be segmented into periods of study. Approximate ages for each period are given here. | |

Development is Multidirectional

The traditional idea—

Sometimes discontinuity is evident: Change can occur rapidly and dramatically, as when caterpillars become butterflies. Sometimes continuity is found: Growth can be gradual, as when redwoods grow taller over hundreds of years. Some characteristics do not seem to change at all: A zygote is XY or XX, male or female, and that chromosomal sex remains throughout the life span. Of course, the significance of that biological fact changes over time.

8

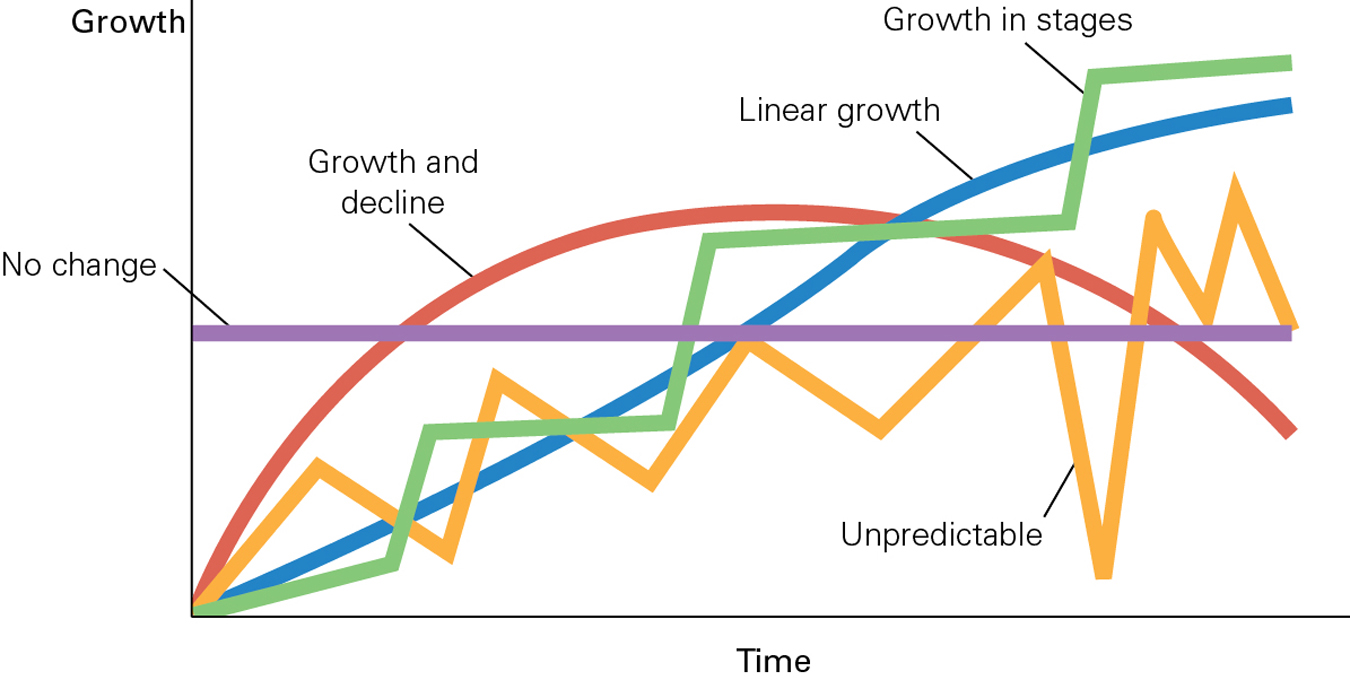

There is simple growth, radical transformation, improvement, and decline as well as stability, stages, and continuity—

The speed and timing of impairments or improvements vary as well. Some changes are sudden and profound because of a critical period, either a time when something must occur to ensure normal development or the only time when an abnormality might occur. For example, the human embryo grows arms and legs, hands and feet, fingers and toes, each over a critical period between 28 and 54 days after conception. After that it is too late: Unlike some insects, humans never grow replacement limbs.

Tragically, between 1957 and 1961, thousands of newly pregnant women in 30 nations took thalidomide, an anti-

Life has very few such critical periods. Often, however, a particular development occurs more easily—

As is often the case with development, sweeping generalizations (like those in the preceding sentence) do not apply in every case. Accent-

9

Development is Multicontextual

The second insight from the life-

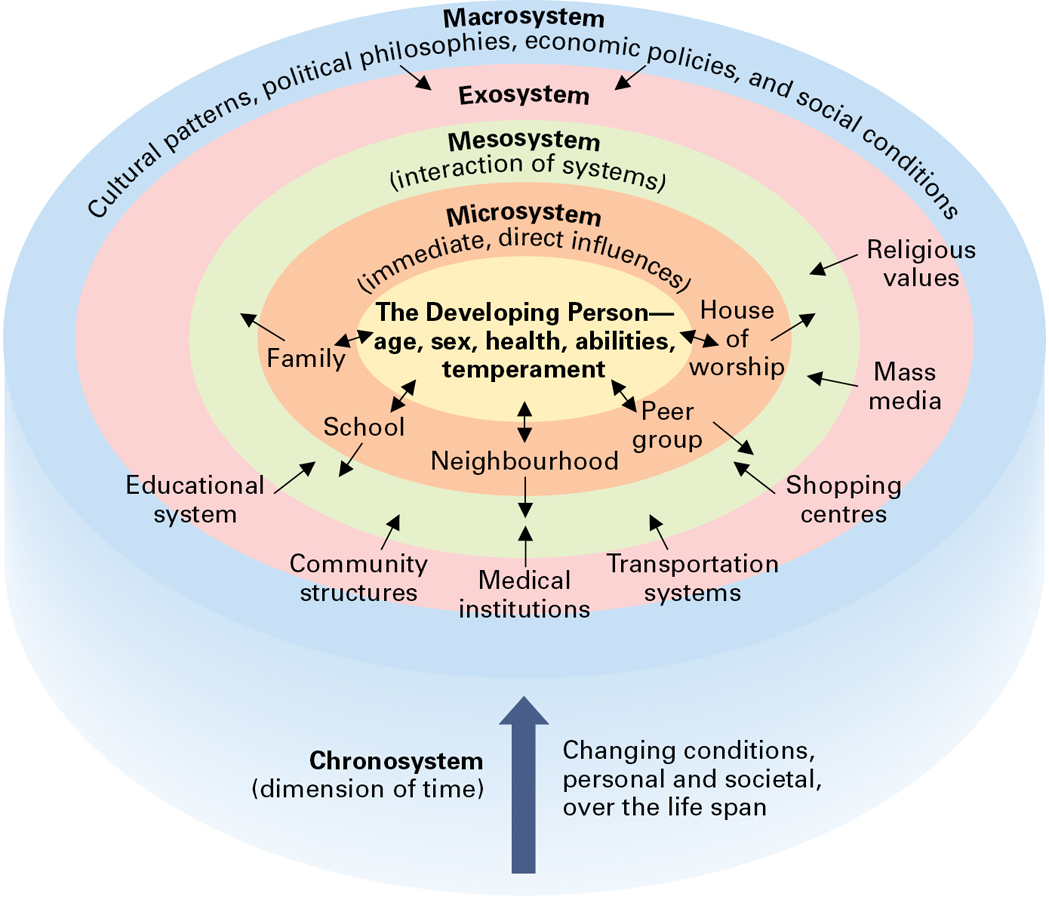

Ecological SystemsThe Russian-

Bronfenbrenner developed his theory of ecological systems by stressing that all relationships the individual person has with other people and with various social contexts are interconnected. He started with the most immediate, direct relationships the child has with his or her immediate family and then worked outward to other environments that might affect the child indirectly.

10

The ecological-

Because he appreciated the dynamic interaction among all the systems, Bronfenbrenner included a fourth system, the mesosystem, consisting of the connections among all the other systems. One example of a mesosystem is the interface between employment (exosystem) and family life (microsystem). These connections include not only the direct impact of family leave, retirement, and shift work, but also indirect macrosystem influences from the economy that affect unemployment rates, minimum wage standards, and hiring practices—

For instance, if one person in a dual-

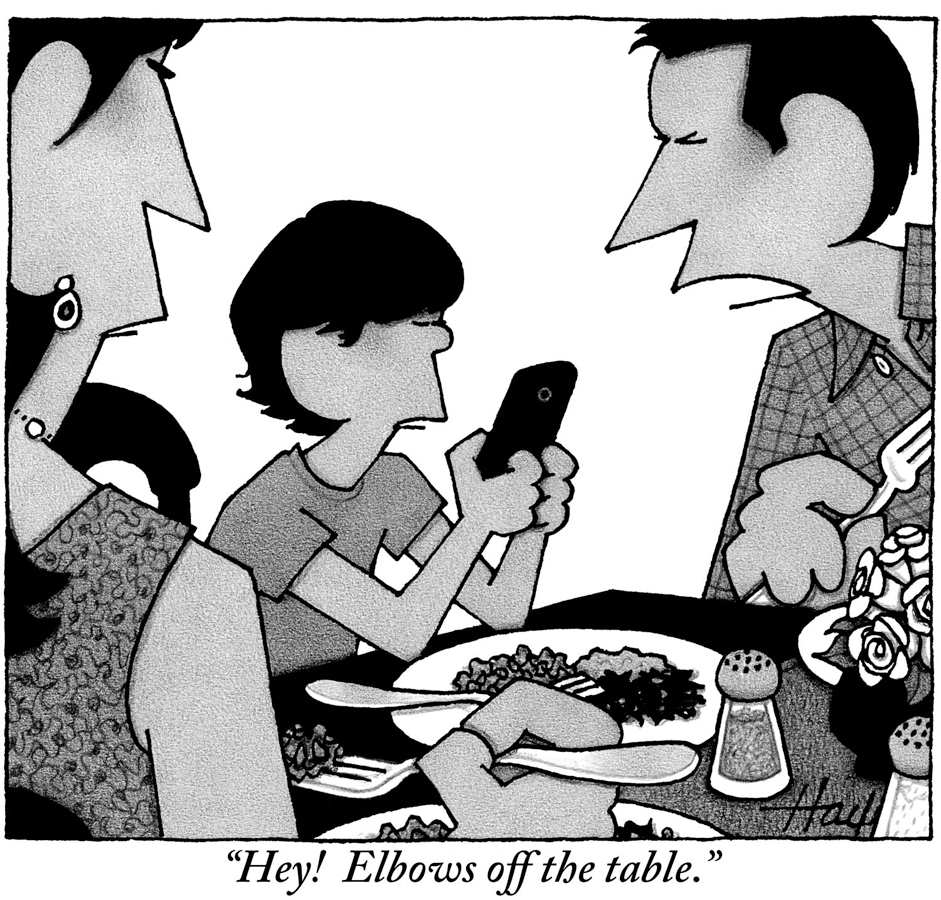

Throughout his life, Bronfenbrenner also stressed the role of historical conditions on human development, and therefore he included a fifth system, the chronosystem (literally “time system”). For example, children growing up with advanced communication technologies such as cellphones, the Internet, and social networking systems like Facebook and Twitter are experiencing and learning about their world differently than children did 50 years ago.

As you can see, a contextual approach to development is complex; many contexts need to be considered. Two of them, the historical and the economic contexts, merit explanation now, as they affect people throughout their lives. Then in the following section we’ll look at the way multicultural contexts can affect individual people and their families, especially as immigration becomes a global phenomenon.

The Historical ContextAll persons born within a few years of one another are said to be a cohort, a group defined by its members’ shared age. Cohorts travel through life together, affected by the interaction of their chronological age with the values, events, technologies, and culture of the era. Ages 18 to 25 are a sensitive period for social values, so experiences and circumstances during emerging adulthood have a lifetime impact. For that reason, attitudes about war and society differ for the Canadian cohorts who were young adults during World War II, during the conflicts in Korea, the Gulf, Afghanistan, or Iraq, or during the wars on poverty, drugs, or terrorism.

As Canadian thinker Marshall McLuhan (1911–

11

AP PHOTO/TONY AVELAR

Think of the many ways Facebook may have affected the development of the cohort popularly known as Generation Z, or the Internet Generation: people born roughly between 1990 and 2001. For example, to what extent will this cohort’s notions of privacy and friendship differ from those of their parents and grandparents? These are questions that developmentalists might pose as the basis for research studies. Researchers in Australia who surveyed Internet users there found that Facebook and other online social networks can allow people to develop relationships they would be reluctant to pursue in person. This in turn increases their psychological well-

The Socioeconomic ContextAnother influential context of development is a person’s socioeconomic status (SES). Sometimes SES is called social class (as in middle class or working class). SES reflects not just income but other aspects, including level of education and occupational status.

Consider two Canadian families. In both, the family composition includes an infant, an unemployed mother, and a father who earns $15 000 a year. The SES of family 1 would be low if the father were a high school dropout who washes dishes for a living and lives in an urban slum. The SES of family 2 would be higher than that of family 1 if the father were a graduate student who works as a teaching assistant, and his family lived in graduate housing on campus. So, the father’s level of education and social status (a graduate student obviously has a greater potential income than a dishwasher) are taken into consideration when determining the family’s SES.

As this example shows, annual income alone does not determine poverty. Rates of inflation also have to be considered, as when the cost of food or gas or other necessities goes up. In Canada, the federal government has no official definition of poverty, low income, or income adequacy. Statistics Canada uses household income to determine whether a family is “living in straitened circumstances.” If a family spends a greater proportion of its income (at least 20 percent more than the average Canadian family) on basic necessities such as food, clothing, and shelter, then it falls beneath what the agency calls a “low income cut-

Statistics Canada calculates both a before-

12

Who is at greatest risk of living in poverty in Canada? Female-

A question for developmentalists is: At what age does low SES do the most damage? In infancy, a family’s low SES may mean less nutritional foods that could stunt the developing brain. In adolescence, low SES could mean a neighbourhood where guns and drugs are readily available. In adulthood, job and marriage prospects are reduced for those with low SES. In late adulthood, accumulated stress over the decades, including the stress of poverty, overwhelms the body’s reserves, causing disease and death (Hoffmann, 2008).

According to Statistics Canada’s 2009 after-

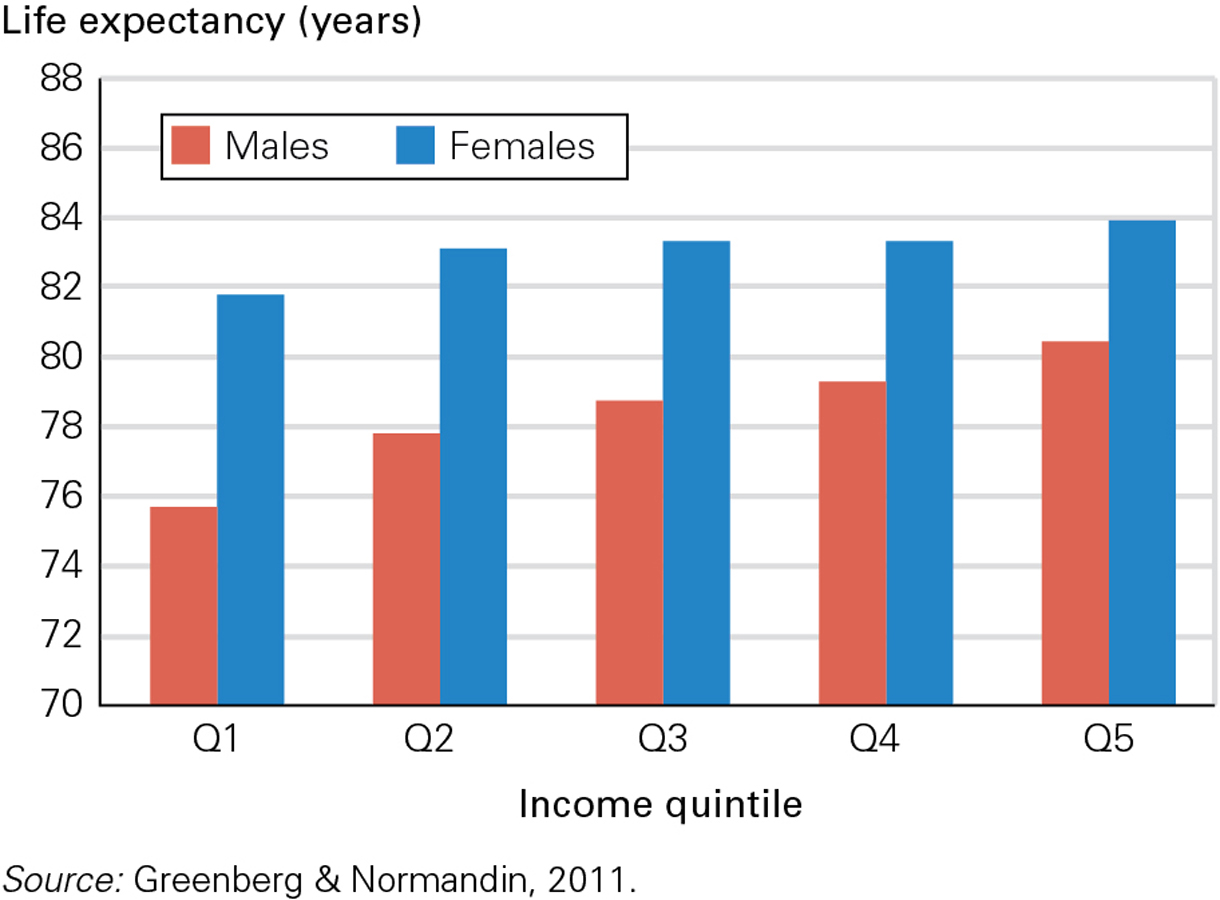

Also important is how nations differ in their response to SES and whether those responses change over time. For example, in Canada, as in the United States, there is a gap in life expectancy between the rich and poor, as evident from Figure 1.4.

What to do about age, economic, national, and historical differences is a political rather than a developmental question. Voters choose leaders who decide policies that affect people of various ages and incomes. At best, developmentalists provide data, not prescriptions.

Development is Multicultural

In order to study “all kinds of people, everywhere, at every age,” as developmental science must do, it is essential that people of many cultures be included. For social scientists, culture is “the system of shared beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviours, expectations and symbolic representations that persist over time and prescribe social rules of conduct” (Bornstein et al., 2011).

Thus, culture is far more than food, clothes, or rituals; it is a set of ideas that people share. This makes culture a powerful social construction, a concept constructed, or made, by a society. Social constructions affect how people think and behave, what they value, ignore, and punish. Because culture is so basic to thinking and emotions, people are usually unaware of their cultural values. Just as fish do not realize that they are surrounded by water, people often do not realize that their assumptions about life and death arise from their own culture.

13

Sometimes people use the word culture to refer to large groups of other people, as in “Asian culture” or “Latino culture.” That invites stereotyping and prejudice, since such large groups include people of many cultures. For instance, people from Korea and Japan are aware of notable cultural differences between themselves, as are people from Mexico and Guatemala. Furthermore, individuals within those cultures sometimes rebel against expected beliefs, conventions, norms, and behaviours.

Culture influences everything we say, do, or think, but the term “culture” needs to be carefully used. Ideally, pride in one’s national heritage adds to personal happiness, but sometimes cultural pride is destructive of both the individual and the community (Morrison et al., 2011; Reeskens & Wright, 2011).

Deficit, or Just Difference?Humans tend to believe that they, their nation, and their cultures are a little better than others. This way of thinking has benefits. Generally, people who like themselves are happier, prouder, and more willing to help others. However, that belief becomes destructive if it reduces respect and appreciation for others. Developmentalists recognize the difference-equals-deficit error, the assumption that people unlike us (different) are inferior (deficit). Think back to high school and the various cliques and groups of people there. Did some groups of students think that they were better than the rest?

The difference-

Sometimes a difference may be connected to an asset (Marschark & Spencer, 2003). For example, cultures that discourage dissent also foster harmony. The opposite is also true—

A multicultural perspective helps researchers realize that whether a difference is an asset or not depends partly on the cultural context. Is the toddler who has a large vocabulary better than the one who knows few words? Is the mother who reads to her child every day better than the mother who does not? Yes to both questions in middle-

14

Another important reason to have a multicultural perspective is to be more sensitive to our biases and how we socially construct our knowledge. For example, for a long time, many researchers concluded that Chinese societies promote interdependence whereas Western countries such as Canada and the United States promote independence. However, researchers such as Chao (1994, 1995) and Chuang (2006) have found that Chinese-

The Multicultural Context in CanadaThe Canadian identity is rooted in multiculturalism and the diversity it encourages. Historically, this diversity has had two major manifestations—

The three founding peoples consist of the Aboriginal peoples, the French, and the English. As the Constitution Act acknowledges, the Aboriginal peoples themselves are subdivided as First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Among the various First Nations peoples across the country, there is also much diversity of languages and cultures.

For various reasons, the English gradually came to be the “dominant” culture in Canada as a whole, and both the Aboriginal peoples and the French have struggled to maintain their distinct identities in the face of this dominance.

For the French, language has always been key to their sense of identity. The right to use French in the courts and Parliament was enshrined in the British North America Act, 1867 and the Constitution Act, 1982, and over the years various federal and provincial/territorial laws have further defined and strengthened these rights. Canada is officially a bilingual nation, and the Official Languages Act states that all federal services must be available in both English and French. It’s also important to remember that the French presence is not limited to Quebec; there are significant francophone communities in New Brunswick (the only officially bilingual province in Canada), Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

One question we’ll pursue throughout this text is: What are the developmental implications of living in a bilingual country? What effects might this have on patterns of language acquisition, on education in general, and on a person’s world view? Could it be that Canadians are a little more cosmopolitan, a little more open to other opinions than their American neighbours, because of the presence of the French and official bilingualism?

Another question we’ll consider is: To what extent have cultural conflicts between Aboriginal peoples and the rest of Canadian society had developmental impacts on Aboriginal persons of all ages? Perhaps the most dramatic example of these conflicts is the residential school system of the twentieth century, when Aboriginal children were taken from their parents and home communities and sent away to schools run by Christian churches. In these schools, young people were forbidden to speak their own language, to participate in their own cultural practices, and for the most part to communicate with their own family members.

15

The negative consequences of these schools were so obvious and grave that the entire system was eventually dismantled and the Canadian government issued a formal apology to all Aboriginal peoples in 2008, calling the residential school system “a sad chapter in our history.” Developmentally speaking, are there lessons to be learned, not just from the residential schools legacy, but from traditional Aboriginal teachings on child rearing and education?

To a large extent, residential schools were an attempt by the government to assimilate Aboriginal peoples into the dominant culture of the time to, in the chilling words of one government official, “kill the Indian in the child.” As the government began to abandon this policy in the 1960s, Aboriginal peoples also acquired, for the first time in Canadian history, the rights of full citizenship. At the same time, Canada began to liberalize its immigration laws, which had always favoured white Europeans and discouraged immigration from Asia, Africa, and South America.

Slowly and sometimes grudgingly, Canadian society began to welcome, even to celebrate, diversity. Part of what makes this cultural diversity possible is what John Berry, emeritus professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, calls acculturation. This is the process of cultural and psychological changes that individuals face as they come into contact with a new culture (Berry et al., 1989). Specifically, it involves all the adjustments immigrants have to make to adapt to their new surroundings while still maintaining their own cultural practices and beliefs.

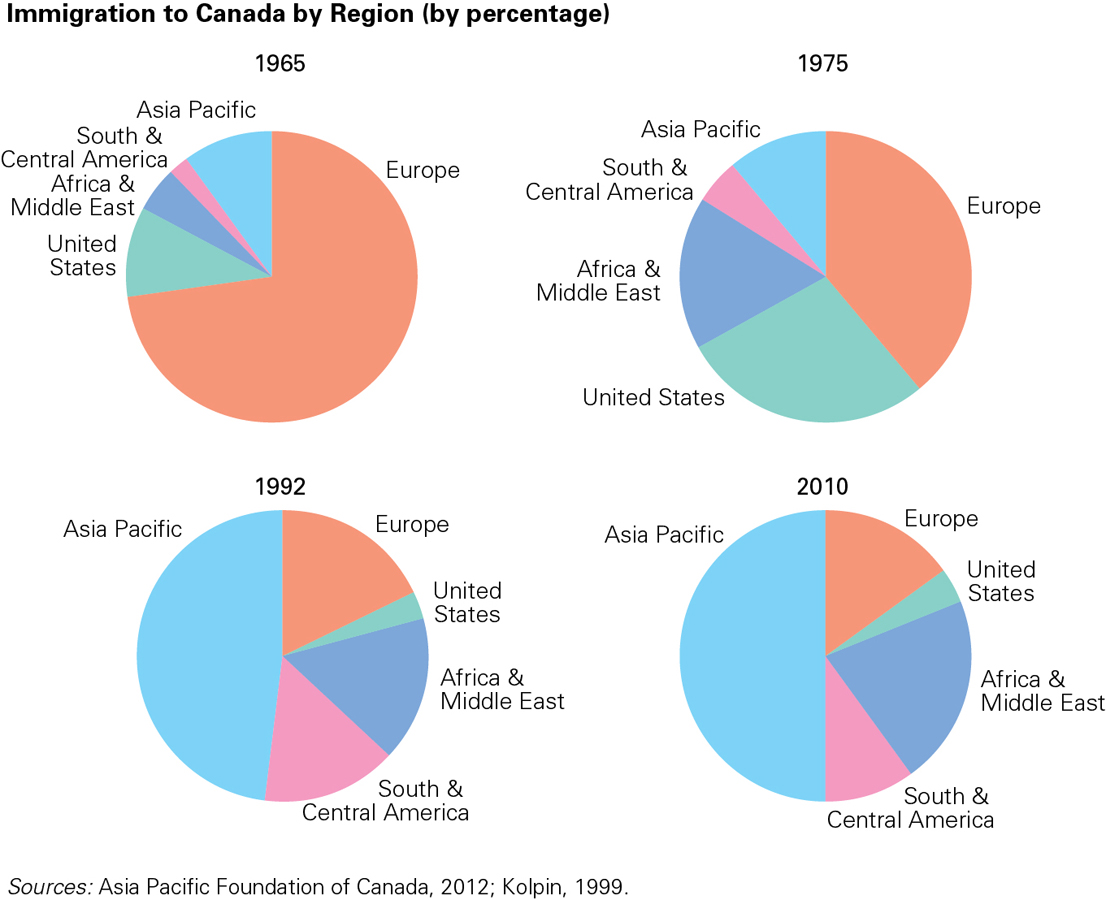

In Canada, the acculturation process has been made easier than in some other countries because of certain government policies and programs that are rooted in the country’s history. As noted above, before the 1960s, Canada’s ethnoprofile was largely European, white, and, except in Quebec, English speaking. Then in 1962 and 1967, largely for economic reasons, the federal government reformed the Immigration Act to remove all existing racial barriers. The result was a major transformation in the number of immigrants coming to Canada from countries in the developing world, a transformation that over the years has completely changed the ethnic profile of Canadian immigration (see Figure 1.5).

To accommodate this change in its immigrant population, the Canadian government under Pierre Trudeau adopted an official policy of multiculturalism in 1971. In 1988, this policy became law through the adoption of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, whose stated objective is to “recognize and promote the understanding that multiculturalism reflects the cultural and racial diversity of Canadian society and acknowledges the freedom of all members of Canadian society to preserve, enhance and share their cultural heritage” (Minister ofJustice, 1988).

16

To strengthen the country’s commitment to immigrant Canadians, the federal and provincial/territorial governments now provide funds to support numerous services and programs specifically targeted to newcomers. By 2011, there were close to 1000 immigrant serving agencies (ISAs)—largely community-

Learning Within a CultureRussian cognitive developmentalist Lev Vygotsky (1896–

Vygotsky (discussed in more detail in Chapter 5) believed that guided participation is a universal process used by mentors to teach cultural knowledge, skills, and habits. Guided participation can occur via school instruction but more often happens informally, through “mutual involvement in several widespread cultural practices with great importance for learning: narratives, routines, and play” (Rogoff, 2003). One example is book reading, as just explained.

Inspired by Vygotsky, Barbara Rogoff studied cultural transmission in Guatemalan, Mexican, Chinese, and American families. Adults always guide children, but clashes occur if parents and teachers are of different cultures. In one such misunderstanding, a teacher praised a student to his mother:

Teacher: Your son is talking well in class. He is speaking up a lot.

Mother: I am sorry.

[Rogoff, 2003]

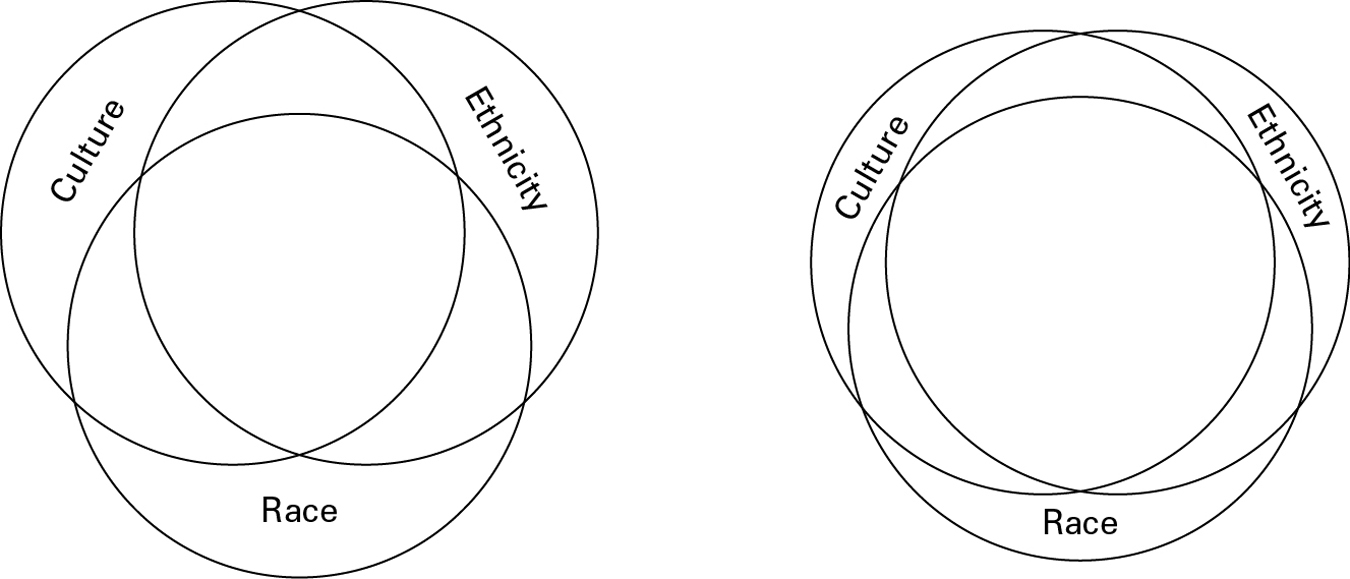

Ethnic and Racial GroupsIt is easy to confuse culture, ethnicity, and race, because these terms sometimes overlap (see Figure 1.6). People of an ethnic group share certain attributes, almost always including ancestral heritage and usually national origin, religion, and language (Whitfield & McClearn, 2005). As you can see from this definition, ethnic groups often share a culture, but this is not necessary. Some people of a particular ethnicity differ culturally (consider people of Irish descent in Ireland, Australia, and Canada), and some cultures include people of several ethnic groups (consider British culture).

17

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Using the Word Race*

The term race has been used to categorize people on the basis of physical differences, particularly outward appearance. Historically, most North Americans believed that race was real, an inborn biological characteristic. Races were categorized by colour: white, black, red, and yellow (Coon, 1962).

It is obvious now, but was not a few decades ago, that no one’s skin is really white (like this page) or black (like these letters) or red or yellow. Social scientists are now convinced that race is a social construction, and that colour terms exaggerate minor differences.

Genetic analysis confirms that the concept of race is based on a falsehood. Although most genes are identical in every human, those genetic differences that distinguish one person from another are poorly indexed by appearance (Race, Ethnicity, and Genetics Working Group of the American Society of Human Genetics, 2005). Skin colour is particularly misleading, since dark-

Race is more than a flawed concept; it is a destructive one. It was used to justify racism, expressed in myriad laws and customs, with slavery, lynching, and segregation directly connected to the idea that race was real. Racism continues in less obvious ways (some highlighted later in this book), undercutting the goal of our science of human development—

Since race is a social construction that continues to lead to racism, some social scientists believe that the term should be abandoned. Ethnic and cultural differences may be significant for development, but racial differences are not. This realization is embedded in the way the United States census reports differences. Race categories began decades ago and the original white and black terms remain. However, Hispanics, first counted separately in 1980, “may be of any race.”

A study of census categories used by 141 nations found that only 15 percent use the word race, and that almost all of them were once slave-

Cognitively, labels encourage stereotyping, and labelling people by race leads to the notion that superficial differences in appearance are significant (Kelly et al., 2010). To avoid racism, one possibility is to avoid using the word race, thereby becoming colour-

But there is a powerful, opposite perspective. In a nation with a history of racial discrimination, reversing that history may require recognizing race, allowing those who have been harmed to be proud of their identity. The fact that race is a social construction, not a biological distinction, does not make it meaningless. Particularly in adolescence, people who are proud of their racial identity are likely to achieve academically, resist drug addiction, and feel better about themselves (Crosnoe & Johnson, 2011).

Furthermore, documenting ongoing racism requires data to show that many medical, educational, and economic conditions—

As you see, strong arguments support both sides of this issue. In this book, we refer to ethnicity more often than to race, but we use race or colour when the original data are reported that way.

*Every page of this text includes information that requires critical thinking and evaluation. In addition, once in each chapter you will find a feature entitled Opposing Perspectives in which an issue is highlighted that has compelling opposite perspectives.

Ethnicity is a social construction, affected by the social context, not a direct outcome of biology. That makes it nurture, not nature. For example, African-

18

Similar identity becomes strengthened and more specific (Sicilian, not just Italian; South Korean, not just East-

Development is Multidisciplinary

Scientists often specialize, studying one phenomenon in one species at one age. Such specialization provides a deeper understanding of the rhythms of vocalization among 3-

However, human development requires insights and information from many scientists, past and present, in many disciplines. Our understanding of every topic benefits from multidisciplinary research; scientists hesitate to apply conclusions about human life until they are substantiated by several disciplines.

Genetics and EpigeneticsThe need for multidisciplinary research became particularly apparent with the onset of genetic analysis. The final decades of the twentieth century witnessed dozens of genetic discoveries, leading to a momentous accomplishment at the turn of the century: The Human Genome Project mapped all the genes that make up a person. To the surprise of many, it is now apparent that every trait—

At first, it seemed that genes might determine everything, that humans became whatever their genes destined them to be—

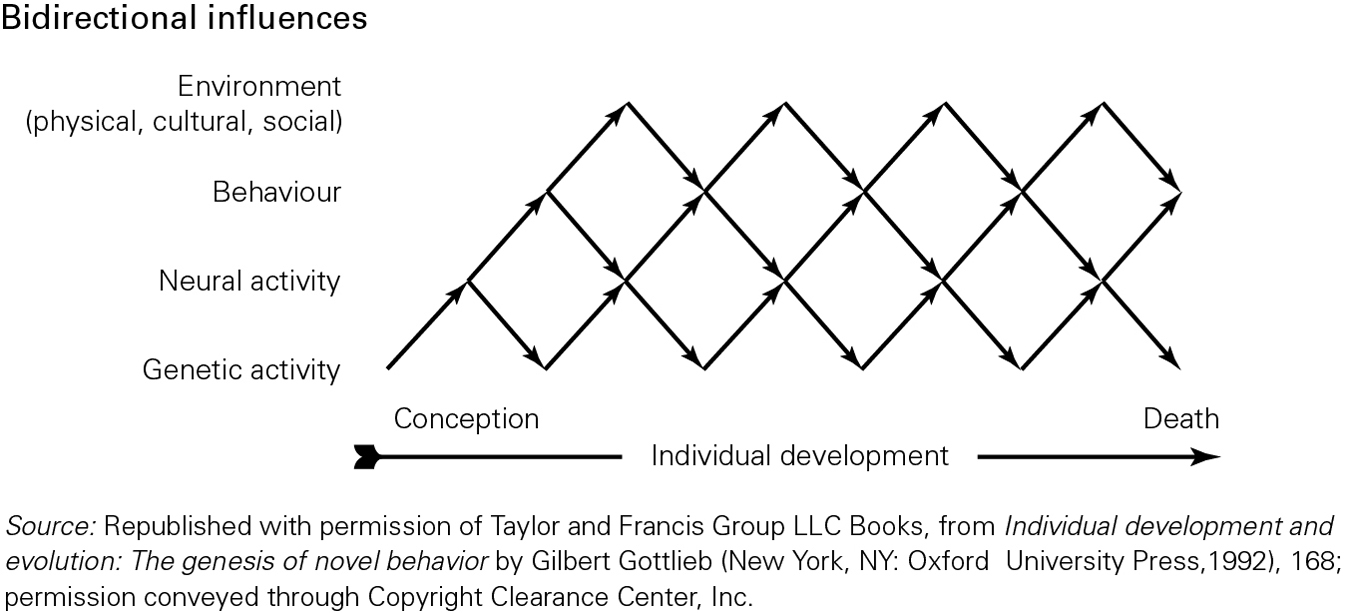

The realization that genes alone do not determine development soon led to the further realization that all important human characteristics are epigenetic. The prefix epi-

Some “epi” influences occur in the first hours of life as biochemical elements silence certain genes, in a process called methylation. The degree of methylation for people changes over the life span, affecting genes (Kendler et al., 2011). In addition, other epigenetic influences occur, including some that impede development (e.g., injury, temperature extremes, drug abuse, and crowding) and some that facilitate it (e.g., nourishing food, loving care, and active play). Research far beyond the discipline of genetics, or even the broader discipline of biology, is needed to discover all the epigenetic effects.

The inevitable epigenetic interaction between genes and the environment (nature and nurture) is illustrated in Figure 1.7. That simple diagram, with arrows going up and down over time, has been redrawn and reprinted dozens of times to emphasize that genes interact with environmental conditions again and again in each person’s life (Gottlieb, 2010).

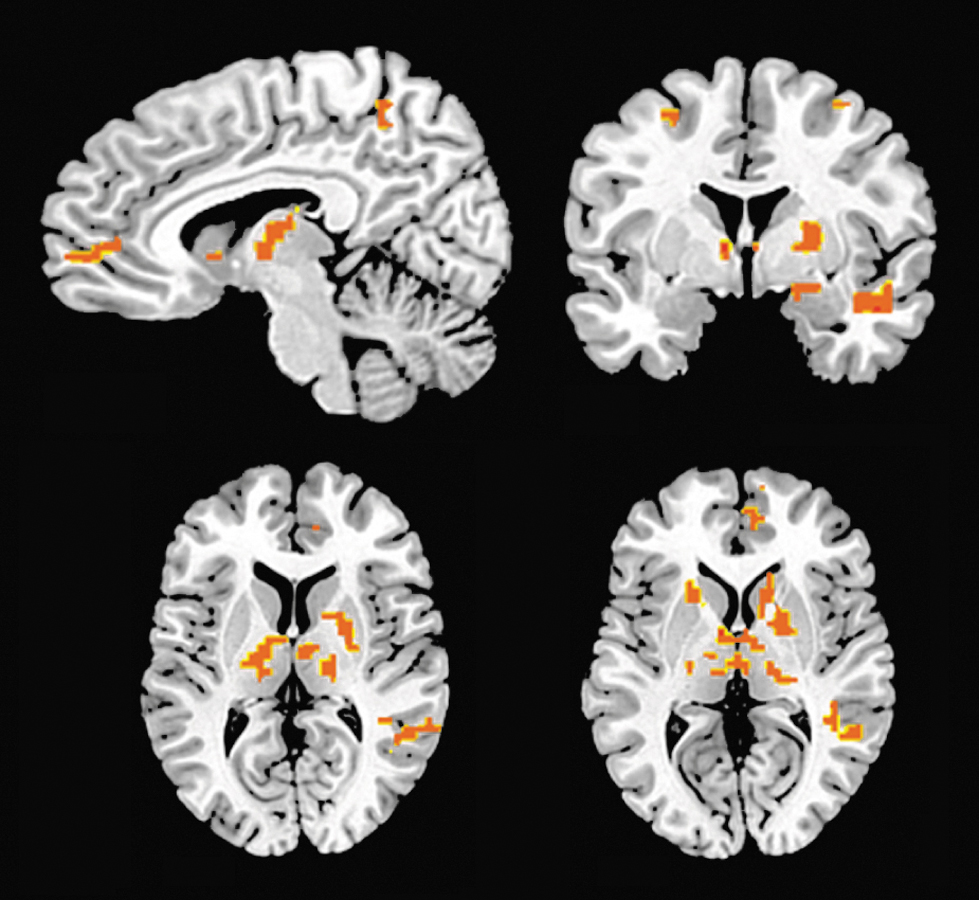

Epigenetic research is especially important in treating diseases that impair the brain and devastate human development. As one group of researchers explains, “Clearly, the brain contains an epigenetic ‘hotspot’ with a unique potential to not only better understand its most complex functions, but also to treat its most vicious diseases” (Gräff et al., 2011). Genes are always important; some are expressed, affecting development, and some are never noticed, from generation to generation, unless circumstances change. The reasons are epigenetic; factors beyond the genes are crucial (Issa, 2011; Skipper, 2011).

19

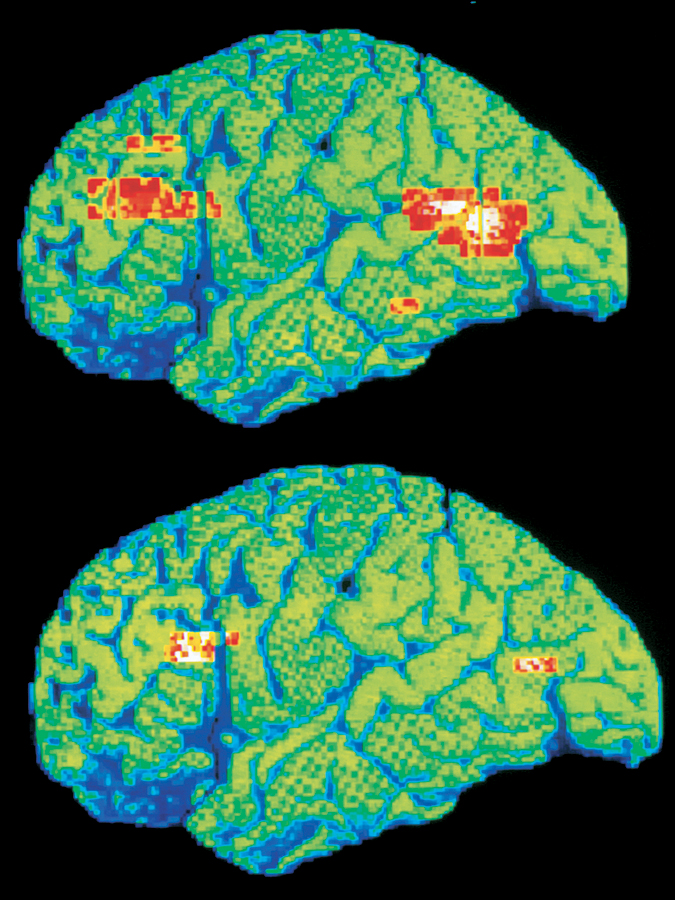

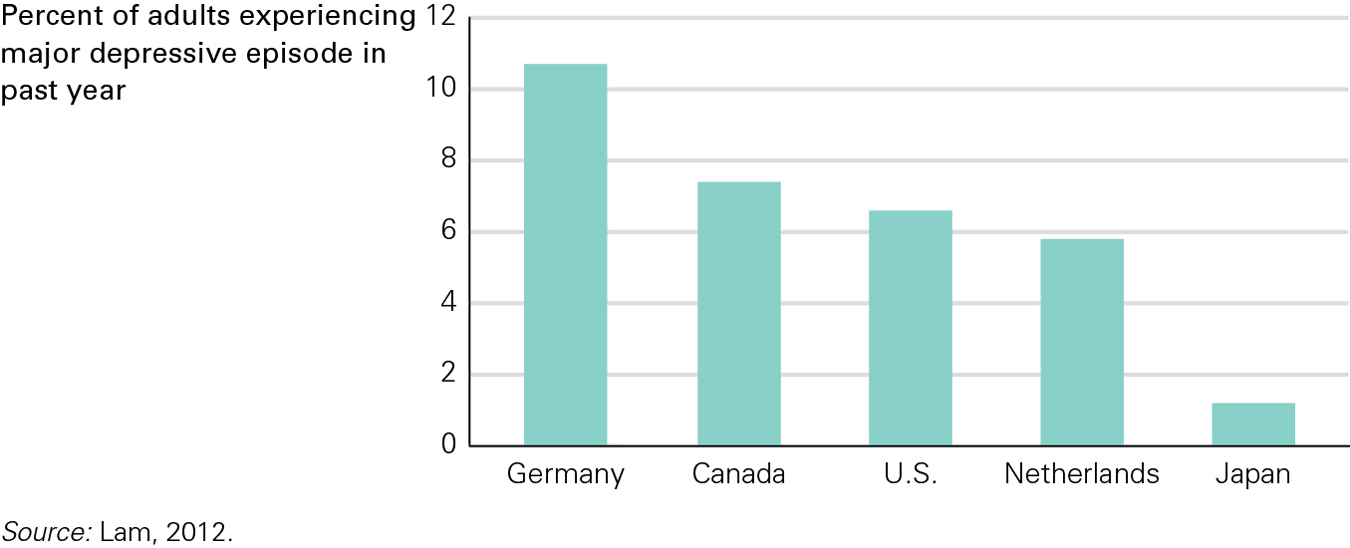

Multidisciplinary Research On DepressionConsider the importance of many disciplines in understanding depression, which results in 65 million lost years of productive life per year around the world (P. Y. Collins et al., 2011). There is no doubt that depression is partly genetic and neurological—

For instance, the incidence of clinical depression suddenly rises in early adolescence, particularly among girls. Throughout life, whether or not a person becomes depressed is affected by chemicals in the brain—

Child-

To speak in a monotone, to keep their faces flat and expressionless, to slouch back in their chair, to minimize touch, and to imagine that they felt tired and blue. The infants…reacted strongly,…cycling among states of wariness, disengagement, and distress with brief bids to their mother to resume her normal affective state. Importantly, the infants continued to be distressed and disengaged…after the mothers resumed normal interactive behavior.

[Tronick, 2007]

Thus, even three minutes of mock-

Many genetic, biochemical, and neurological factors distinguish adults with depression from other adults (Kanner, 2012; Poldrack et al., 2008). However, their moods and behaviours are powerfully affected by experience and cognition (Huberty, 2012; van Praag et al., 2004). Again, nature is affected by nurture. A person with depressing relationships and experiences is likely to develop the brain patterns characteristic of depression, as well as vice versa. Overall, at least 12 factors are linked to depression:

- Low serotonin in the brain, as a result of an allele of the gene for serotonin transport (neuroscience)

20

- Childhood caregiver depression, especially postpartum depression with exclusive mother-

care (psychopathology) - Low exposure to daylight, as in winter in higher latitudes (biology)

- Malnutrition, particularly low hemoglobin (nutrition)

- Lack of close friends, especially when a person enters a new culture, school, or neighbourhood (anthropology)

- Diseases, including Parkinson’s and AIDS, and drugs to treat diseases (medicine)

- Disruptive event, such as a breakup with a romantic partner (sociology)

- Death of mother before age 10 (psychology)

- Absence of father during childhood—

especially because of divorce, less so because of death or migration (family studies) - Family history of eating disorders (not necessarily of the depressed person) (genetics)

- Poverty, especially in a nation where some people are very wealthy (economics)

- Low cognitive skills, including illiteracy and lack of exposure to other ideas (education).

As you see, each of these factors arises from research in a different discipline (italicized). Of course, disciplines overlap. Lack of close confidants, for instance, is noted by anthropologists, but also by sociologists and psychologists. Furthermore, culture, climate, and politics all have an effect, although the particulars are debatable. For example, consider the national differences in Figure 1.8. There are at least six explanations for the disparity in the incidence of depression between one nation and another—

A multidisciplinary approach is crucial in alleviating every impairment, including depression. Currently in North America, a combination of cognitive therapy, family therapy, and antidepressant medication is often more effective than any one of these three alone. International research finds that depression is relatively high in some populations in some places (e.g., among half the women in Pakistan) and low in others (e.g., among about 3 percent of the non-

As already noted in our discussion of nature and nurture, of SIDS, and of the story of watching Caleb’s birth, no single factor determines any outcome. In fact, some people who experience one, and only one, of the factors above never experience depression. It is a combination that makes a person depressed. As you will now learn, for genetic and other reasons, some people are severely affected by circumstances that do not bother others. The multidisciplinary approach to the life span adds a measure of caution to every scientist: No one is able to predict with certainty the future developmental path for anyone.

21

Development is Plastic

The term plasticity denotes two complementary aspects of development: Human traits can be moulded (as plastic can be) and yet people maintain a certain durability of identity (as plastic does). The concept of plasticity in development provides both hope and realism—

Dynamic SystemsThe concept of plasticity is basic to the contemporary understanding of human development. This is evident in one of the newest approaches to understanding human growth, an approach called dynamic systems. The idea is that human development is an ongoing, ever-

Seasons change in ordered measure, clouds assemble and disperse, trees grow to a certain shape and size, snowflakes form and melt, minute plants and animals pass through elaborate life cycles that are invisible to us, and social groups come together and disband.

[Thelen & Smith, 2006]

Note the key word dynamic: Physical and emotional influences, time, and each person and every aspect of the environment are always interacting, always in flux, always in motion. This approach builds on many aspects of the life-

An Example of Interacting Systems

My sister-

Remember, plasticity cannot erase a person’s genes, childhood, or permanent damage. David’s disabilities are always with him (he still lives with his parents). But his childhood experiences gave him lifelong strengths. His family loved and nurtured him (consulting the Kentucky School for the Blind when he was a few months old, enrolling him in four preschools and then in public kindergarten at age 6). By age 10, David had skipped a year of school and was a fifth grader, reading at the eleventh-

David now works as a translator of German texts, which he enjoys because, he says, “I like providing a service to scholars, giving them access to something they would otherwise not have” (David Stassen, personal communication, 2007). As his aunt, I have seen him repeatedly defy predictions. All five of the characteristics of the lifespan perspective are evident in David’s life, as summarized in TABLE 1.2.

| Characteristic | Application in David’s Story |

|---|---|

| Multidirectional. Change occurs in every direction, not always in a straight line. Gains and losses, predictable growth, and unexpected transformations are evident. | David’s development seemed static (or even regressive, as when early surgery destroyed one eye) but then accelerated each time he entered a new school or college. |

|

Multidisciplinary. Numerous academic fields— |

Two disciplines were particularly critical: medicine (David would have died without advances in surgery on newborns) and education (special educators guided him and his parents many times). |

| Multicontextual. Human lives are embedded in many contexts, including historical conditions, economic constraints, and family patterns. | The high SES of David’s family made it possible for him to receive daily medical and educational care. His two older brothers protected him. |

|

Multicultural. Many cultures— |

Appalachia, where David and his family lived, has a particular culture, including acceptance of people with disabilities and willingness to help families in need. Those aspects of that culture benefited David and his family. |

| Plasticity. Every individual, and every trait within each individual, can be altered at any point in the life span. Change is ongoing, although neither random nor easy. | David’s measured IQ increased from about 40 (severely mentally retarded) to about 130 (far above average), and his physical disabilities became less crippling as he matured. Nonetheless, because of a virus contracted before he was born, the course of his life changed forever. |

22

Differential SensitivityAs just noted, plasticity emphasizes that people can and do change, that predictions are not always accurate. This is sometimes frustrating to scientists, who seek to prevent problems by learning what is particularly risky or helpful for healthy development.

Three insights have improved predictions. Two of them you already know: (1) nature and nurture always interact, and (2) certain periods of life are sensitive periods, more affected by particular events than others. This was apparent for David: his inherited characteristics affected his ability to learn and his early childhood education (a sensitive period for language learning) has helped him throughout his life.

The third factor to aid prediction and thus target intervention is a more recent discovery, differential sensitivity. The idea is that some people are more vulnerable than others to particular experiences.

Can you remember something you heard in childhood that still affects you, such as a criticism that stung or a compliment that motivated you? Now think of what that same comment meant to the person who uttered it, or what it might have meant to another child. A particular comment stayed with you, but for most people, the same words would be forgotten. That is differential sensitivity.

Generally, many scientists have found many genes, or circumstances, that work both ways—

23

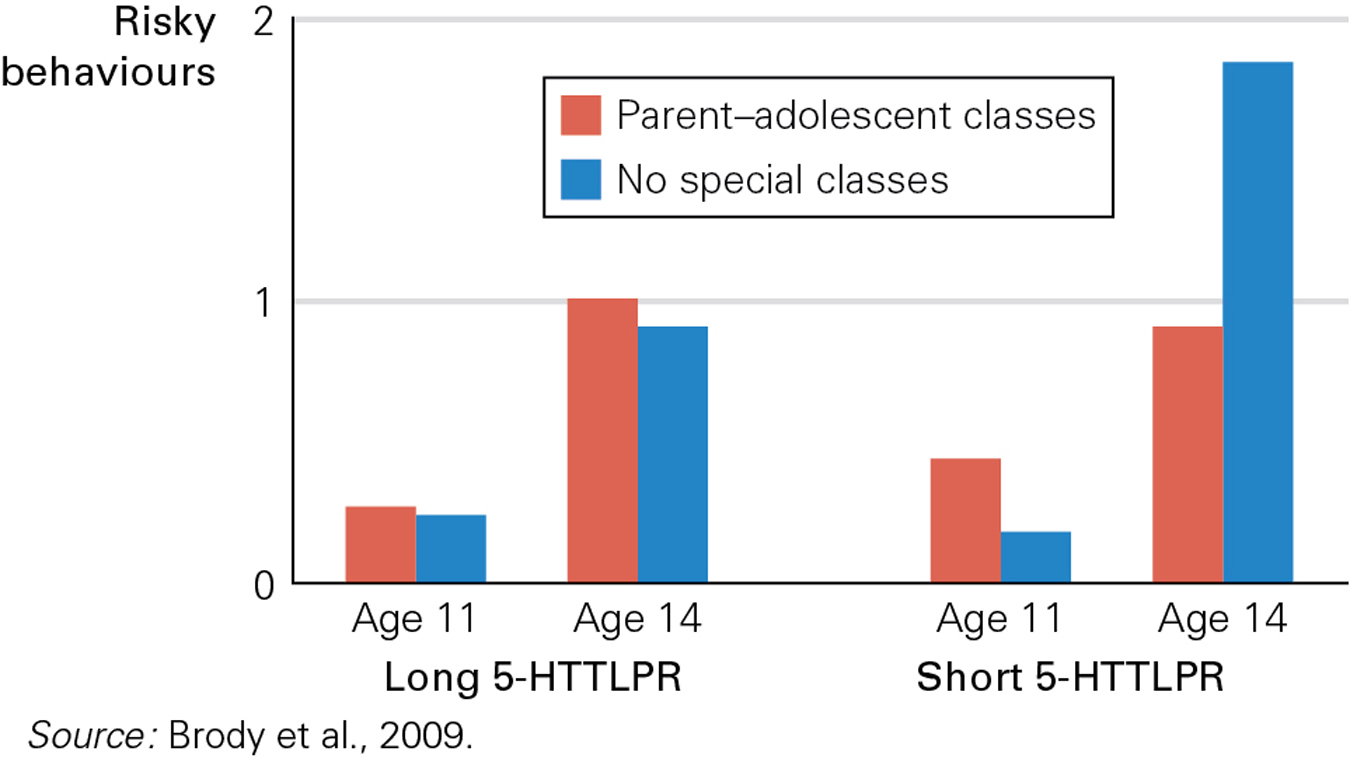

Here is one example that began with African-

Accordingly, they randomly divided parents and sons into two groups: (1) a group that had no intervention, and (2) a group that attended seven seminars designed to increase racial pride, family support, honest communication, and compliance with parents’ rules. These features are in keeping with replicated research that finds that pride and parental involvement protect against early sex and drug use.

The first follow-

That small genetic difference turned out to be critical: Those with the long version developed just as well whether they were in the intervention group or not. However, teenagers with the short version who attended the seminars were less likely to have early sex or to use drugs than those who had the short gene but not the family training (see Figure 1.9). The sensitivity provided by nature (the small difference in the code for 5-

KEY Points

- Development is multidirectional, with gains and losses evident at every stage and in every domain.

- Development is multicontextual, with the ecological context from the immediate family to the broad social environment affecting every person. Cohort and socioeconomic status have powerful impacts.

- Cultural influences are sometimes unrecognized until another culture is understood. Social constructions, including ethnicity and race, are tangled with cultural values, making culture not only crucial but complex.

- Many academic disciplines provide insight on how people grow and change over time, as the interaction of all the developmental contexts and domains cannot be fully grasped by any one discipline.

- Each person’s development is plastic, with the basic substance of each individual life mouldable by contexts and events, sometimes in differential ways, making every person unlike any other person.

24