Becoming Your Own Person

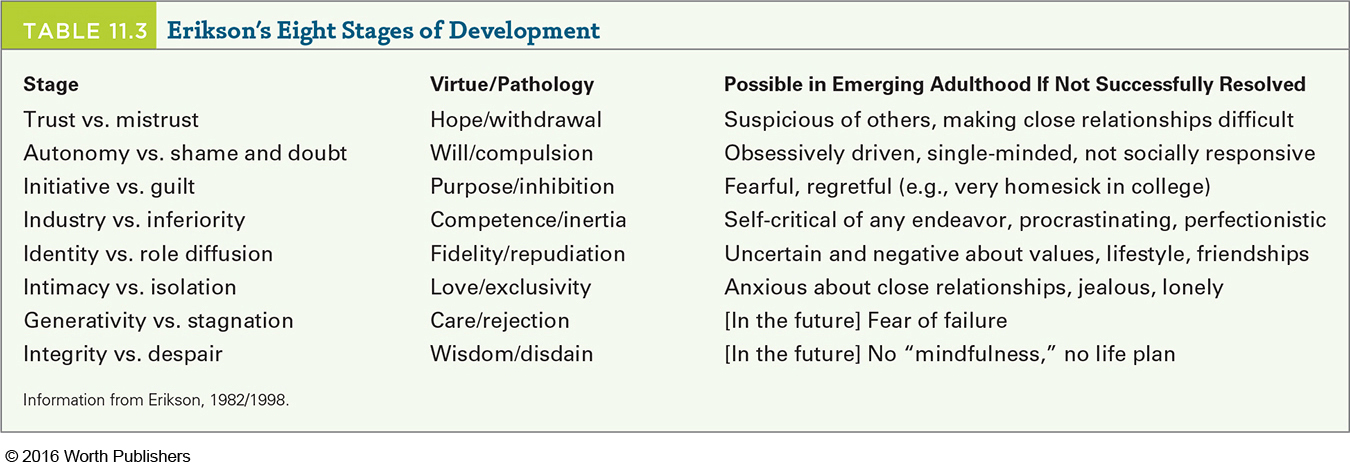

A theme of all human development is that continuity and change are evident throughout life. In emerging adulthood, the legacy of childhood is apparent amidst new achievements. Erikson recognized this ongoing process in his description of the fifth of his eight stages, identity versus role confusion.

Remember that the identity crisis begins in adolescence, when teenagers reexamine the identities their parents imposed on them. However, as you learned, the identity crisis is not usually resolved in adolescence.

Identity Achievement

Erikson believed that the outcome of earlier crises provides the foundation for each new stage. The identity crisis is an example (see Table 11.3).

Certainly the adolescent push for independence from parents is often expressed in a search for self-

All four identity statuses (achievement, foreclosure, moratorium, diffusion) are evident in emerging adulthood, as the identity crisis continues (Schwartz et al., 2011). At least in developed nations, it seems normative for emerging adults to question who they really are in the four areas that Erikson originally termed—

CHANGING STATUS Many young adults change their identity status in the years after age 25. A detailed, longitudinal study in Sweden (Carlsson et al., 2015) found that some (41 percent) had achieved identity by age 25, and some (32 percent) had foreclosed. But many of those changed (most often from foreclosure to achievement) in the next few years. The group who changed most often were in moratorium at age 25. Almost all (94 percent) changed status by age 29, usually to achievement but sometimes to foreclosure.

The main finding of that study, however, was not change in status but in depth; identity often became deeper, more reflective, and meaningful during the 20s, as life experiences require the various aspects of identity to come together. One example was Alice, who at 25 was considering several possible careers. By age 29 she was midway through an advanced degree in archeology, a firm choice. Thus, her vocational identity had been achieved.

Alice’s gender identity seemed firm at age 25: She wanted to marry and have a child, and she said this was more important than her career. But by age 29, although she had become a wife and mother, she said, “To me children should never hinder me from doing what I want, and a job should never hinder me from having children. It just can’t be like that” (Carlsson et al., 2015, p. 340).

This determination to “have it all” (family and vocation) is part of identity achievement among many contemporary young adults. This is apparent not only in nations at the forefront of emerging adulthood (such as Sweden) but also among younger adults with advanced education in other nations (Montez et al., 2014; Mishra, 2014).

Research on almost 2,000 German emerging adults found that, for men as well as women, commitment to both work and family is the combination most likely to lead to emotional satisfaction. However, in that study only 18 percent of emerging adults had reached firm identity achievement in both domains (Luyckx et al., 2013). (The work/family conflict is discussed in Chapter 13.)

CAREERS Developmental psychologists influenced by Erikson, and emerging adults themselves, consider establishing a vocational identity part of growing up (Arnett, 2004). Emerging adulthood is a “critical stage for the acquisition of resources”—-including the education, skills, and experience needed for vocational success (Tanner et al., 2009, p. 34).

Current emerging adults often quit one job and seek another. Between ages 18 and 25, the average U.S. worker changes jobs every year, with the college-

Readiness to seek a new job is less problematic for young workers themselves, since exploration is part of their identity search. However, prolonged unemployment is a problem. The economic recession has been particularly harsh on the current cohort of young adults, as their unemployment rate is close to double that of older job seekers. In Europe as well as North America, unemployment during emerging adulthood is common, leading to anxiety and depression (Arnett et al., 2014).

Emerging adulthood is a crucial time for developing values regarding work, such as whether job security and salary (extrinsic rewards) are more important than joy of doing the work one loves (intrinsic rewards). The particular work values that emerging adults develop are likely to be affected by the current worldwide economic recession, an example of the exosystem shaping this cohort in ways their parents did not experience (Johnson et al., 2012; Chow et al., 2014).

Personality in Emerging Adulthood

Both continuity and change are evident in personality lifelong. Temperament, childhood trauma, and emotional habits endure: If self-

Yet personality is not static. After adolescence, new characteristics appear and negative traits diminish. Emerging adults make choices that break with the past. In modern times, this age period is characterized by years of freedom from a settled lifestyle, which allows shifts in attitude and personality.

Overall, a study with almost a million adolescents and adults from 62 nations found that “during early adulthood, individuals from different cultures across the world tend to become more agreeable, more conscientious, and less neurotic” (Bleidorn et al., 2013, p. 2530). One reason for this improvement is that emerging adults increasingly feel in control of their lives, able to make their own decisions, which often includes enrolling in more education. This sense of control continued to increase after emerging adulthood if at least one of their parents had been to college (Vargas Lascano et al., 2015).

RISING SELF-

This positive trend of increasing happiness has become more evident over recent decades. One reason may be the nature of emerging adulthood: Perhaps contemporary young adults are more likely to make their own life decisions and move past the role confusion at the beginning of the identity search (Schwartz et al., 2011).

PLASTICITY Emerging adults are open to new experiences (a reflection of their cognition and adventuresome spirit), and this allows personality shifts as well as eagerness for more education (McAdams & Olson, 2010). Going to college, leaving home, paying one’s way, stopping drug abuse, moving to a new city, finding satisfying work and performing it well, making new friends, committing to a partner—

Total transformation does not occur; genes, childhood experiences, and family circumstances always affect people. Nor do new experiences necessarily lead to improvement. Cohort effects are part of the picture: Perhaps the rising self-

Intimacy

intimacy versus isolation

The sixth of Erikson’s eight stages of development. Adults seek someone with whom to share their lives in an enduring and self-

In Erikson’s theory, after achieving identity, people experience the sixth crisis of development, intimacy versus isolation. This crisis arises from the powerful desire to share one’s personal life with someone else. Without intimacy, adults suffer from loneliness and isolation. Erikson (1993) explains:

[T]he young adult, emerging from the search for and the insistence on identity, is eager and willing to fuse his identity with that of others. He is ready for intimacy, that is, the capacity to commit himself to concrete affiliations and partnerships and to develop the ethical strength to abide by such commitments, even though they call for significant sacrifices and compromises.

[p. 263]

The urge for social connection is a powerful human impulse, one reason our species has thrived. Other theorists use different words (affiliation, affection, interdependence, communion, belonging, love) for the same human need. Attachment experienced in infancy may well be a precursor to adult intimacy, especially if the person has developed a working model of attachment (Chow & Ruhl, 2014; Phillips et al., 2013). Adults seek to become friends, lovers, companions, and partners.

All intimate relationships (friendship, family ties, and romance) have much in common—

As Erikson (1993) explains, to establish intimacy, the emerging adult must

face the fear of ego loss in situations which call for self-

[pp. 263–

EMERGING ADULTS AND THEIR PARENTS Before turning to the romantic needs of emerging adults, we need to acknowledge the ongoing role of parents. It is hard to overestimate the importance of the family during any period of the life span.

Although a family is made up of individuals, families are much more than the persons who belong to it. In the dynamic synergy of a well-

If anything, parents today are more important to emerging adults than ever. Two experts in human development write: “With delays in marriage, more Americans choosing to remain single, and high divorce rates, a tie to a parent may be the most important bond in a young adult’s life” (Fingerman & Furstenberg, 2012).

linked lives

When the success, health, and well-

All members of each family have linked lives; that is, the experiences and needs of family members at one stage of life are affected by those at other stages (Elder, 1998; Macmillan & Copher, 2005). We have seen this in earlier chapters: Children are affected by their parents’ relationship, even though they are not directly involved in their parents’ domestic disputes, financial stresses, parental alliances, and so on. Brothers and sisters can be abusers or protectors, role models for good or for ill.

Many emerging adults still live at home, though the percentage varies from nation to nation. Almost all unmarried young adults in Italy and Japan live with their parents. Fewer do so in the United States, but many parents underwrite their young-

helicopter parent

The label used for parents who hover (like a helicopter) over their emerging adult children.

There is a downside to parental support: It may impede independence. The most dramatic example is the so-

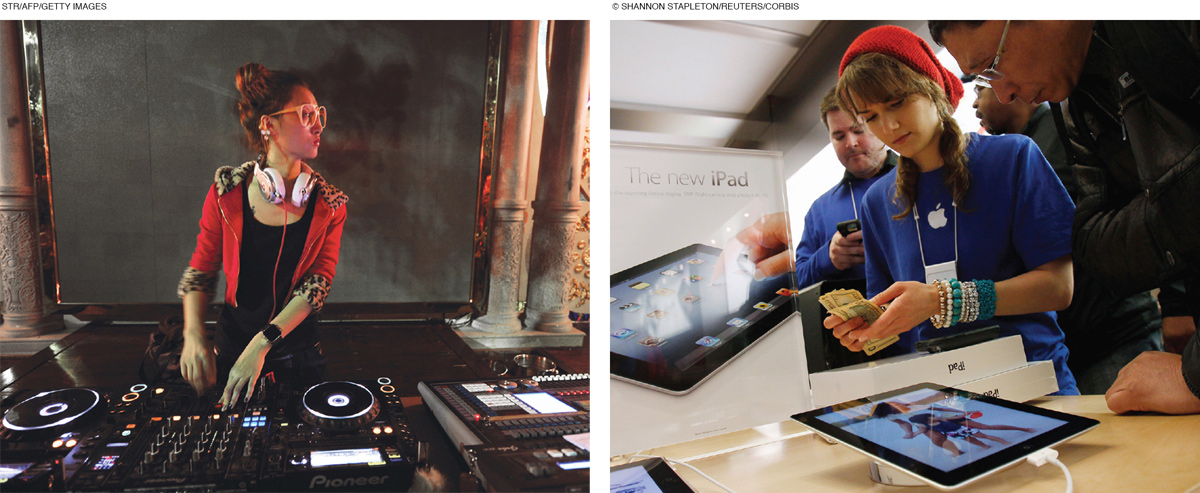

FRIENDSHIP Because emerging adults are entering the worlds of work, college, and community, they have more friends at this time of life than at any other period. They need friends to navigate all their new experiences.

According to a recent theory, an important aspect of close human connections is “self-

Whether or not friends expand our minds, it is certain that friends strengthen our mental and physical health (Seyfarth & Cheney, 2012). Unlike relatives, friends are chosen (not inherited); they seek understanding, tolerance, loyalty, affection, and humor from one another—

Friendships “reach their peak of functional significance during emerging adulthood” (Tanner & Arnett, 2011, p. 27). Since fewer emerging adults have the obligations and close relationships that come with spouses, children, or frail parents, their friends provide companionship and critical support. Friends comfort each other when romance turns sour; they share experience and knowledge about everything from what college to choose to what jeans to wear.

Self-

Emerging adults often use social media to extend and deepen friendships that begin face to face, becoming more aware of the day-

GENDER DIFFERENCES A meta-

By contrast, men are less likely to touch each other except in aggressive activities, such as competitive athletics or military combat. The butt-

Often emerging adults have close friends of both sexes, which is particularly helpful when they seek romance. Problems arise if outsiders assume that every male–

Keeping a male–

ROMANTIC PARTNERS What researchers call romantic competence is multifaceted, with “mutual caring, trust, emotional closeness; concern for, and sensitivity to, the needs . . . of others . . . and valuing faithfulness, loyalty, and honesty” (Raby et al., 2015, p. 117). The ability to be a good partner is nurtured from childhood, with attachment relationships—

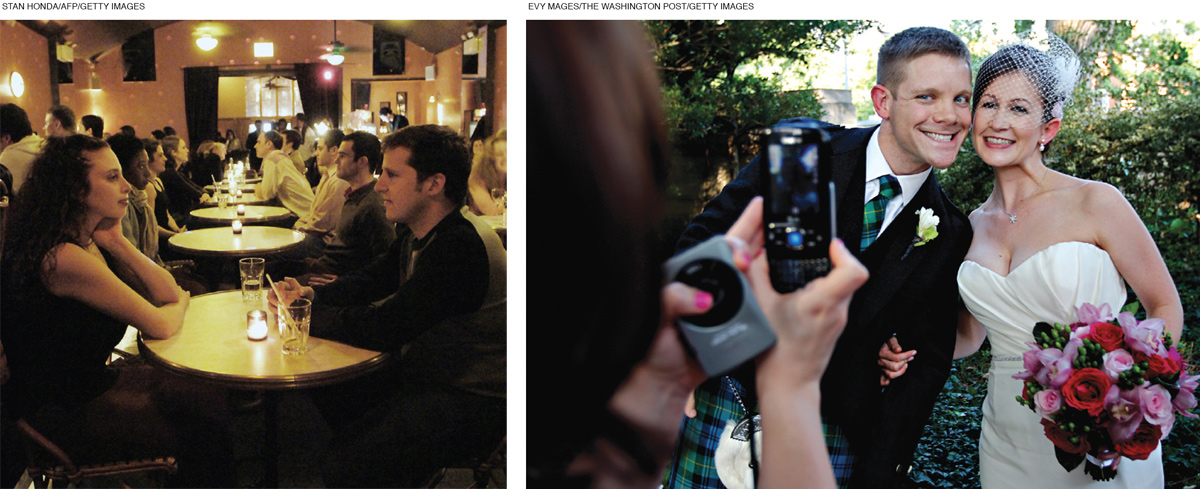

Love, romance, and commitment are important for emerging adults, although specifics have changed. Most emerging adults are thought to be postponing, not abandoning, marriage, often because they want a college degree and a steady income first.

The fact that millions of gay and lesbian couples seek to marry and have successfully won that right in the Supreme Court of the United States and in many other nations indicates that marriage is still considered crucial by many. Indeed, the opposition to same-

From a developmental perspective, cohort and culture are pivotal in couple formation and bonding. Three distinct patterns are evident. Historically, and currently in many parts of the world, love did not precede marriage because parents arranged marriages to join two families together.

A second mode, in other places and times, allowed some freedom of choice, but adolescents met only a select group. (Single-

In this second mode, when two people decided to marry, the parents had to agree—

In former times, almost all marriages were of these two types; young people almost never met and married people unknown to their parents. Currently, in developing nations, a pattern called modern traditionalism often blends these two. For example, in Qatar, couples believe they have a choice, but more than half the marriages are between cousins, anticipated by relatives from the time they were children (Harkness & Khaled, 2014).

The third pattern is relatively new, although familiar to most readers of this book. Young people socialize with hundreds of others and pair off but do not marry until they are able, financially and emotionally, to be independent. Their choices tilt toward personal qualities observable at the moment (physical appearance, personal hygiene, personality, sexuality, a sense of humor), not to qualities more important to parents (religion, ethnicity, politeness, long-

For most emerging adults, love is considered a prerequisite and sexual exclusiveness is expected, as found in a survey of 14,121 people of many ethnic groups and sexual orientations (Meier et al., 2009). They were asked to rate from 1 to 10 (with 1 lowest and 10 highest) the importance of money, same racial background, long-

Faithfulness to one’s partner was considered most important of all (rated 10 by 89 percent), and love was almost as high (rated 10 by 86 percent). By contrast, most thought being of the same race did not matter much (57 percent rated it 1, 2, or 3). Money, while important to many, was not nearly as crucial as love and fidelity.

This survey was conducted in North America, but emerging adults worldwide share many of the same values. For example, 6,000 miles away, emerging adults in Kenya also reported that love was the primary reason for couples to connect and stay together; money was less important (S. Clark et al., 2010). A survey of 11,300 adults seeking partners in China found, as expected, that commitment was crucial but also found, unexpectedly, that love, “American style” was sought (Lange et al., 2015).

FINDING A PARTNER From an evolutionary perspective, the emphasis on love and fidelity is not surprising. It may be that romantic love has been crucial for the survival of the human species for thousands of years. The different strategies for couple formation, including arranged marriages and polygamy, may be considered various ways to foster the love that binds couples together (Fletcher et al., 2015).

Thus the emphasis on love is worldwide, but other people remain influential, even when individuals say “all you need is love.” Romantic attachments may not be selected by friends and family, but young people still are influenced by the opinions of other people: Sometimes they contradict parental advice, but that is more likely with cohabitation than marriage. Usually contrary choices are made reluctantly, not defiantly (Sinclair et al., 2015).

Traditionally, when parents did not arrange contact, friends did. Young people were invited to parties, set up for “blind” dates, introduced to people thought to be suitable. That is less true today.

One major innovation of the current cohort of emerging adults is the use of social media. Web sites such as Facebook and Instagram allow individuals to post their photos and personal information on the Internet, sharing the details of their daily lives with thousands of others. College students almost all (93 percent) use social media sites, particularly to connect with each other (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2014). Many also use Internet dating sites to find potential partners.

Parents sometimes worry that their adult children will be taken advantage of by online predators, but most emerging adults are selective and careful in their online matches. Another problem may appear, however. Social networking may produce dozens of potential partners, increasing choice overload when too many options are available.

Online dating encourages screening out potential mates for superficial reasons, and then choice overload increases second thoughts. Young adults may become too picky and critical of their own decisions (should I have contacted the other one instead?), or, overloaded with possibilities, refuse to make any selection (none of them is perfect) (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000; Reutskaja & Hogarth, 2009).

Choice overload has been demonstrated with consumer goods—

THINK CRITICALLY: Does the success of marriages between people who met online indicate that something is amiss with more traditional marriages?

About a third of all marriages in the United States are the result of online matches between people unknown to friends or parents. Surprisingly, when online connections lead to face-

hookup

A sexual encounter between two people who are not in a romantic relationship. Neither intimacy nor commitment is expected.

HOOKUPS WITHOUT COMMITMENT A sexual relationship that is not intended to become a romance, with no true intimacy or commitment, is a hookup. When this relationship occurred in prior generations, it was either prostitution or illicit, as in a “fling” or a “dirty secret.” No longer.

It is estimated that about half of all emerging adults have hooked up. Hookups often involve intercourse, but not necessarily: The crucial factor is that sexual interaction of some sort occurs between partners who do not know each other well, perhaps having met just a few hours before.

Hookups are more common among first-

Males are more likely to hook up than females (Roberson et al., 2015). This is true for heterosexual as well as homosexual men. It seems that the desire for physical intimacy without emotional commitment is stronger in young men than in young women, either for hormonal (testosterone) or cultural (women want committed fathers if children are born) reasons. One sociologist writes:

While women are preparing for adult life, guys are in a holding pattern. They’re hooking up rather than forming the kind of intimate romantic relationships that will ready them for a serious commitment; taking their time choosing careers that will enable them to support a family; and postponing marriage, it seems, for as long as they possibly can.

[Kimmel, 2008, p. 259]

Cohabitation

cohabitation

An arrangement in which a couple live together in a committed romantic relationship but are not married.

The fact that marriage is often postponed, and that sex sometimes occurs without commitment, does not mean that emerging adults do not want a committed romantic partnership. In fact, having a steady partner is still sought, and those in romantic relationships tend to be happier and healthier than their lonely peers. What has changed is the rise of cohabitation, as living with an unmarried partner is called.

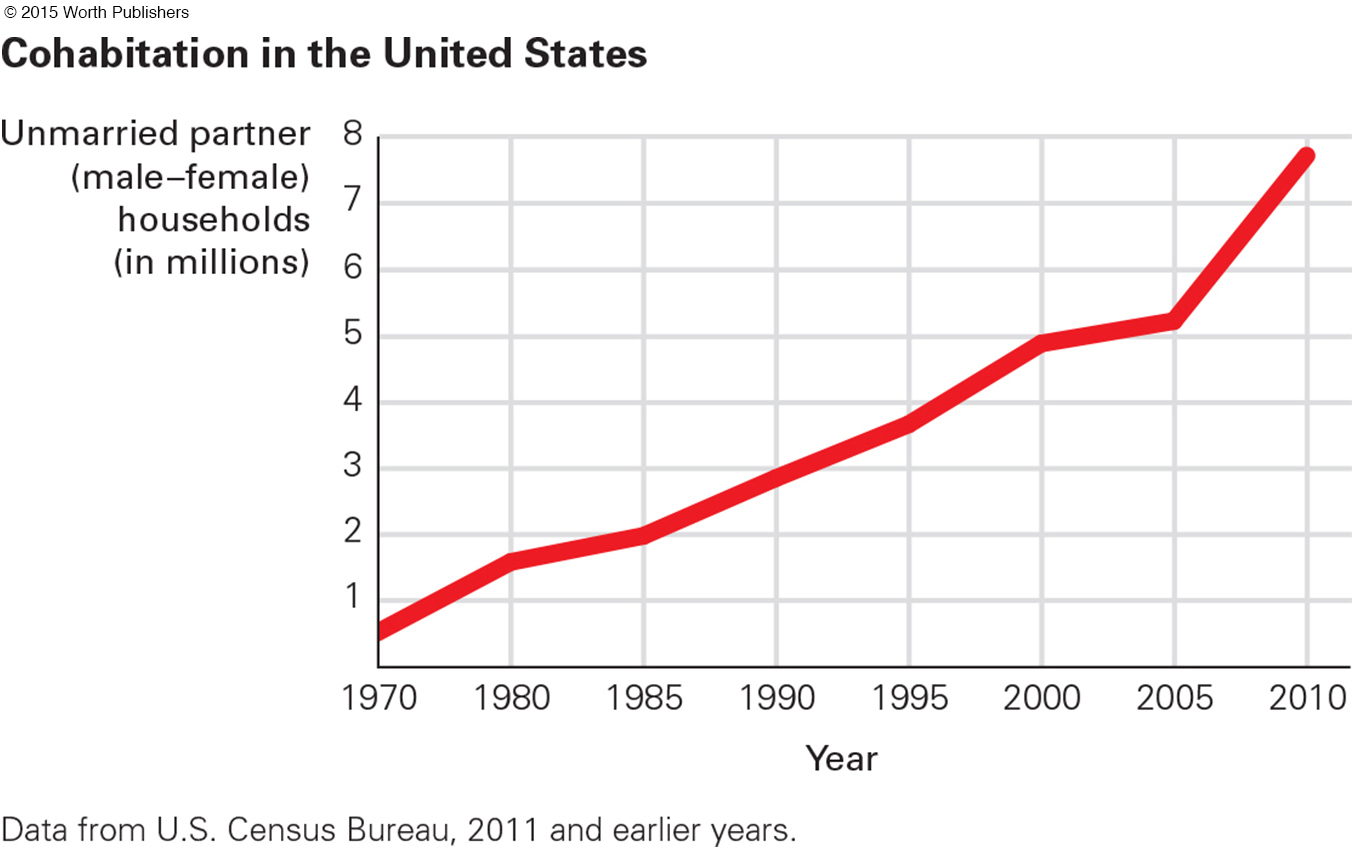

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN COHABITATION Cohabitation was relatively unusual 40 years ago: In the United States, less than 1 percent of all households were made up of a cohabiting man and woman (see Figure 11.6). Now cohabitation is the norm.

Cohabitation rates vary from nation to nation. Almost everyone in some nations cohabits at some point—

In other nations—

Everywhere, culture matters. Research in 30 nations finds that acceptance of cohabitation within a nation affects the happiness of those who cohabit there. Within each of those 30 nations, demographic differences (such as education, income, age, and religion) affect the happiness gap between cohabiting and married people (Soons & Kalmijn, 2009), but generally those who are within a community where everyone cohabits are least likely to be harmed by it.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSEQUENCES OF COHABITATION Many emerging adults consider cohabitation to be a wise choice as a prelude to marriage, a way for people to make sure they are compatible before tying the knot and thus reducing the chance of divorce. However, research suggests the opposite.

Contrary to widespread belief, living together before marriage does not prevent problems after a wedding. In a meta-

Some emerging adults want to avoid old traditions and believe that cohabitation allows a couple to have the advantages of marriage without the legal and institutional trappings. But cohabitation is unlike marriage in many ways. Cohabiters are less likely to pool their money, less likely to have close relationships with their parents or their partner’s parents, less likely to take care of their partner’s health, more likely to be criminals, and more likely to break up (Forrest, 2014; Guzzo, 2014; Hamplová et al., 2014).

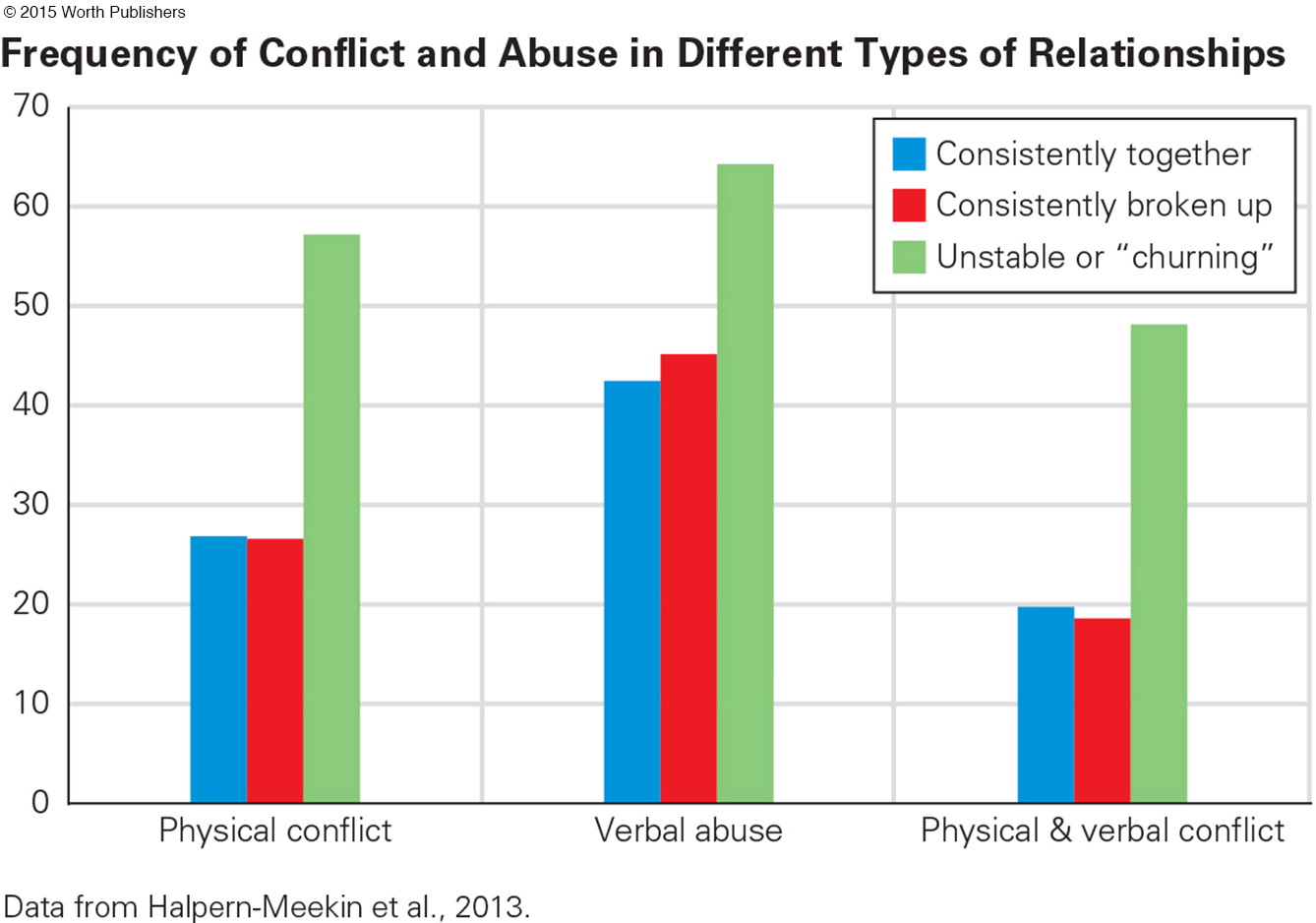

Particularly problematic is churning, when couples live together, then break up, then get back together. Churning relationships have high rates of verbal and physical abuse (Halpern-

Although the research suggests many problems with cohabitation, most emerging adults do it, and most of their grandparents did not. Of course, humans tend to justify whatever they do. In this case, cohabiting adults typically think they have found intimacy without the restrictions of marriage, but they may be fooling themselves.

There is an important caveat with all this research on the consequences of cohabitation. Much of it is based on people who cohabited 10 or 20 years ago. They were more rebellious and less religious than those who did not cohabit; that might explain why they were more likely to divorce if they did marry. Current research finds the implications of cohabitation less negative (Copen et al., 2013).

All the research finds that cohabitation has one decided advantage and one decided disadvantage. The advantage is financial: People save money by living together. The disadvantage occurs if children are born: Cohabiting partners are less committed to the long decades of child rearing, and their children are less likely to excel in school, graduate, and go to college.

One other long-

Looking at the broad picture of human development, it is clear that every human of every cohort and culture benefits from a satisfying and enduring relationship. Emerging adults achieve romantic partnership in ways not chosen several generations ago, and they relate to parents and friends more intensely than ever. Some choices and partners are harmful, but overall, social isolation harms everyone of any age, so the impulse to connect should not be squashed (Holt-

This prepares us for the next period of development, adulthood. At that time, most people are immersed in a large social world, connecting to elders and children as well as partners and coworkers. On to Chapter 12.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.18

1. How is attending college a moratorium?

A more mature response to the identity crisis is to seek a moratorium—

Question 11.19

2. Why is vocational identity particularly elusive in current times?

Due to changes in the world of work (e.g., commitment to a particular career may limit vocational success) and the larger society (e.g., economic recessions), achieving a single vocational identity may not be possible or even desirable. Vocational flexibility may be required for future generations.

Question 11.20

3. How does personality change from adolescence to adulthood?

Personality is shaped lifelong by genes and early experiences. After adolescence, new personality dimensions may appear. The freedom of emerging adults allows shifts in attitude and personality. For most emerging adults, transitions that result from deliberate choices increase well-

Question 11.21

4. What is the general trend of self-

Self-

Question 11.22

5. What kinds of support do parents provide their young-

Parents provide emotional support, financial support, tuition support, and housing.

Question 11.23

6. What do emerging adults seek in a close relationship?

Emerging adults emphasize the importance of friendship with their romantic partners. They expect shared confidences and loyalty from their romantic partners.

Question 11.24

7. How has the process of mate selection changed over the past decades?

The use of social media has dramatically changed the way emerging adults find romantic partners. Hookups—

Question 11.25

8. Why do many emerging adults cohabit instead of marrying?

There are national differences in the acceptance and timing of cohabitation. Cohabitation can be viewed as a prelude to marriage, a way to see if couples are compatible, a substitute for marriage, or a practical way to save money by sharing living expenses.

Question 11.26

9. What are the advantages and disadvantages of cohabitation?

Cohabitation is advantageous for emerging adults who want to avoid old traditions and have the advantages of marriage without the legal and institutional trappings. But cohabiters are less likely to pool their money, less likely to have close relationships with their parents or their partner’s parents, less likely to take care of their partner’s health, more likely to be criminals, and more likely to break up.