Theories of Late Adulthood

Some elderly people run marathons and lead nations; others no longer walk or talk. Social scientists theorize about this diversity, yet everyone respects her.

Self Theories

self theories

Theories of late adulthood that emphasize the core self, or the search to maintain one’s integrity and identity.

Certain theories of late adulthood can be called self theories; they focus on individuals, especially the self-

THE SELF AND AGING Perhaps people become more truly themselves with age. That is what Anna Quindlen found:

It’s odd when I think of the arc of my life, from child to young woman to aging adult. First I was who I was. Then I didn’t know who I was. Then I invented someone and became her. Then I began to like what I’d invented. And finally I was what I was again. It turned out I wasn’t alone in that particular progression.

[Quindlen, 2012, p. ix]

Older adults maintain their self-

A central idea of self theory is that each person ultimately depends on himself or herself. As one woman explained:

I actually think I value my sense of self more importantly than my family or relationships or health or wealth or wisdom. I do see myself as on my own, ultimately . . . Statistics certainly show that older women are likely to end up being alone, so I really do value my own self when it comes right down to things in the end.

[quoted in Kroger, 2007, p. 203]

Self theory is one explanation for an interesting phenomenon: Compared to younger adults, older people rely more on their personal experiences than on objective statistics, or, in dual-

For example, one research team asked, “What does one do when rational deliberation suggests calling it off with Julie to commit to Jane, but a powerful gut feeling suggests just the opposite?” (Mikels et al., 2012, p. 1). In an experiment, blindfolded participants (aged, on average, 21 or 75) were challenged to pick a red jelly bean from one of two dishes, each with more white beans than red. The odds of success for each dish were clearly labeled. There were 12 trials, each with another pair of dishes and set of odds.

The elders did not always make the logical choice. Thirty-

integrity versus despair

The final stage of Erik Erikson’s developmental sequence, in which older adults seek to integrate their unique experiences with their vision of community.

INTEGRITY The most comprehensive self theory came from Erik Erikson. His eighth and final stage of development, integrity versus despair, requires adults to integrate their unique experiences with their community concerns (Erikson et al., 1986/1994). The word integrity is often used to mean honesty, but it also means a feeling of being whole, not scattered, and comfortable with oneself. The virtue of old age, according to Erikson, is wisdom, which implies a broad perspective.

As an example of integrity, many older people are proud of their personal history. They glorify their past, even boasting about bad experiences such as skipping school, taking drugs, escaping arrest, or being physically abused. Psychologists sometimes call this the “sucker to saint” phenomenon, when people interpret their experiences as signs of their nobility (saintly), not their stupidity (Jordan & Monin, 2008).

As Erikson explained it, such self-

life brings many, quite realistic reasons for experiencing despair: aspects of a past we fervently wish had been different; aspects of the present that cause unremitting pain; aspects of a future that are uncertain and frightening. And, of course, there remains inescapable death, that one aspect of the future which is both wholly certain and wholly unknowable. Thus, some despair must be acknowledged and integrated as a component of old age.

[Erikson et al., 1986/1994, p. 72]

Integration of death and the self is the crucial accomplishment of this stage. The life review (explained in Chapter 14) and the acceptance of death (explained in the Epilogue) are crucial aspects of the integrity envisioned by Erikson (Zimmerman, 2012).

Self theory may explain why many of the elderly strive to maintain childhood cultural and religious practices. For instance, grandparents may painstakingly teach a grandchild a language that is rarely used, or they may encourage the child to repeat traditional rituals and prayers. In cultures such as the United States that emphasize newness, elders worry that their traditional values will be lost and thus that they themselves will disappear.

As Erikson wrote, the older person

knows that an individual life is the accidental coincidence of but one life cycle with but one segment of history; and that for him all human integrity stands or falls with the one style of integrity of which he partakes. . . . In such a final consolation, death loses its sting.

[Erikson, 1968/1994, p. 104]

HOLDING ON TO THE SELF Most older people consider their personalities and attitudes quite stable over their life span, even as they acknowledge physical changes of their bodies and gaps in their memory (Klein, 2012). One 103-

Many older people refuse to move from drafty and dangerous dwellings into smaller, safer apartments because leaving familiar places means abandoning personal history. That is irrational, but it is explained by self theory. Likewise, an older person may avoid surgery or refuse medicine because they fear anything that might distort their thinking or emotions: Their priority is self-

compulsive hoarding

The urge to accumulate and hold on to familiar objects and possessions, sometimes to the point of their becoming health and/or safety hazards. This impulse tends to increase with age.

The insistence on protecting the self may explain compulsive hoarding, saving reams of old papers, books, mementos . . . anything that might someday be useful. The fifth edition of the DSM recognizes hoarding as a psychological disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, pp. 247–

Earlier DSM editions did not consider hoarding a disorder. Why not? Many elderly hoarders grew up in the Great Depression and World War II, when saving scraps and reusing products meant survival and patriotism. That habit is contrary to the current ethos: Expiration dates are now stamped on food and drugs; electronics, from computers to televisions, are quickly obsolete.

A prime motive for elderly hoarders is avoiding waste. Hoarding brings them emotional satisfaction (Frost et al., 2015), which a younger person might get from the opposite action, replacing something old. (My youngest daughter enjoys throwing out everything in my refrigerator that has an expiration date that has passed.)

A contemporary problem is that fewer dwellings have attics and basements, so hoarding occurs within living areas. In cramped apartments, hoarding takes over, becoming not only irrational but sometimes dangerous. Self theory helps explain what social workers and younger relatives do not understand: Possessions are part of self-

THINK CRITICALLY: Is hoarding a universal disorder or a cohort problem?

My friend Doris (opening anecdote) hoards old newspaper articles, records, and other things that are precious to her. She lives alone, with her possessions and two cats. She has an answering machine and a fax, but she proudly resists the Internet. She likes it that way.

socio-

The theory that older people prioritize regulation of their own emotions and seek familiar social contacts who reinforce generativity, pride, and joy.

SOCIO-

Socio-

Selectivity is central to self theories. Individuals set personal goals, assess their abilities, and figure out how to accomplish their goals despite limitations. When older people are resilient, they maintain their identity despite wrinkles, slowdowns, and losses, and their emotional health is preserved (Resnick et al., 2011).

positivity effect

The tendency for elderly people to perceive, prefer, and remember positive images and experiences more than negative ones.

An outgrowth of both socio-

For that reason, stressful events (economic loss, serious illness, death of friends or relatives) become less central to identity with age. Because elders think of themselves more positively, they protect their emotional health (Boals et al., 2012), becoming more optimistic about themselves and happier because of it. A strong sense of self-

The positivity effect may explain why, in every nation and religion, older people tend to be more patriotic and devout than younger ones. They see their national history and religious beliefs in positive terms, and they are proud to be themselves—

Anna Quindlen was quoted as glad she “was what I was again.” Does this mean that she, and most older people, do not see current world problems? Consider my daughter, my mother, and me.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Too Sweet or Too Sad?

When I was young, I liked movies that were gritty, dramatic, violent. My mother questioned my choices; I told her I hated sugar-

Now my youngest daughter wants me to read dystopian novels. Hunger Games is an example. I tell her the world has enough poverty and conflict; I don’t need to read about imaginary killing. Have I become my mother?

THINK CRITICALLY: Does the positivity effect avoid reality, or was my mother right?

Many researchers have found that a positive worldview increases with age. The positivity effect correlates with believing that life is meaningful. Elders who are happy, not frustrated or depressed, agree strongly that their life has a purpose (e.g., “I have a system of values that guides my daily activities” and “I am at peace with my past”) (Hicks et al., 2012). Meaningfulness and positivity correlate with a long and healthy life.

The elderly are quicker to let go of disappointments, thinking positively about going forward. As a result, many studies have found “an increase in emotional well-

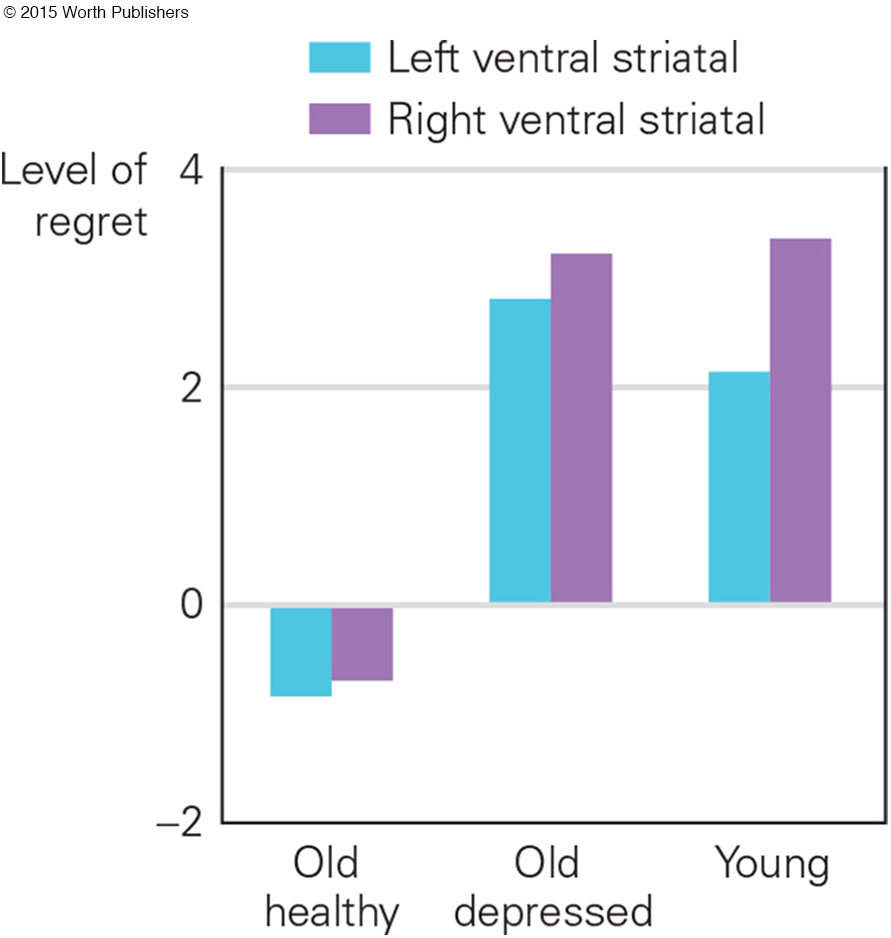

Researchers have measured reactions to disappointment, not only in attitudes and actions but also in brain activity and heart rate. One study compared three groups: young adults, healthy older adults, and older adults with late-

In reaction to disappointment, the healthy older adults recovered quickly, but the other two groups took longer: The brains, bodies, and behavior of the depressed elders and the younger adults were similar, but the healthy elders had broken free of those destructive forces The conclusion: “emotionally healthy aging is associated with a reduced responsiveness to regretful events” (Brassen et al., 2012, p. 614) (see Figure 15.1).

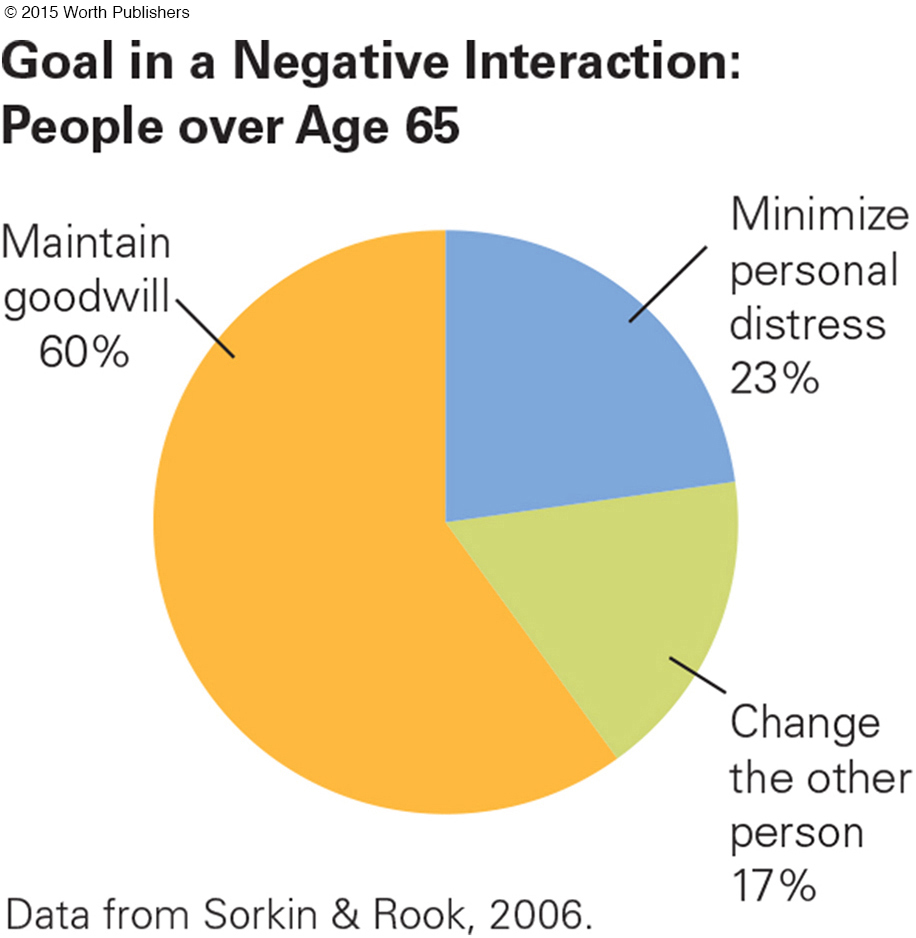

A pair of researchers asked whether the positivity effect in social interaction occurred because older adults simply avoided unpleasant people (Luong & Charles, 2014). Accordingly, they assigned younger and older adults to work on a task with a disagreeable partner.

In fact, that partner was an actor, trained to be nasty with everyone. For example, the actor never smiled, and said, “I really don’t see where you’re coming from.” True to expectations, compared to the younger participants, the older adults more often reported that they liked the partner and enjoyed the task. They did not try to change their partner or feel resentful; the positivity effect protected them (see Figure 15.2).

One perspective is that anger and frustration are useful emotions. From that viewpoint, too much rosy acceptance may be wrong in a world that needs changing, and that may be annoying to younger people who interpret life differently. My daughter recently apologized for criticizing me. I replied, honestly, that I had forgotten her critique. I do not think that was what she wanted to hear. Do I ignore criticism? Am I stuck in my ways?

Back to the study of the nasty partner. The elders’ blood pressure rose less and came down more quickly than did the younger adults’ pressure after the disagreeable interaction. The pulse of the older participants hardly changed at all (Luong & Charles, 2014). Having a positive outlook not only makes a person happier, it also makes them healthier.

Stratification Theories

stratification theories

Theories that emphasize that social forces, particularly those related to a person’s social stratum or social category, limit individual choices and affect a person’s ability to function in late adulthood because past stratification continues to limit life in various ways.

A second set of theories, called stratification theories, emphasizes social forces that position each person in a social stratum or level. That positioning creates disadvantages for some and advantages for others.

Stratification begins in the womb, as “individuals are born into a society that is already stratified—

Every form of stereotyping makes it more difficult for people to break free from social institutions that assign them to a particular path. The results are cumulative, over the entire life span (Brandt et al., 2012).

For instance, as described in many of the preceding chapters, children who are both African American and poor are more likely to be underweight at birth; less likely to talk at age 1 or read before age 6; more likely to drop out of school and use drugs; less likely to obtain a college degree, find a job, or marry; and finally, more likely to die before age 70 of cancer, diabetes, heart disease, or other serious health problems. Each of these outcomes is more likely because of the pre`ious one.

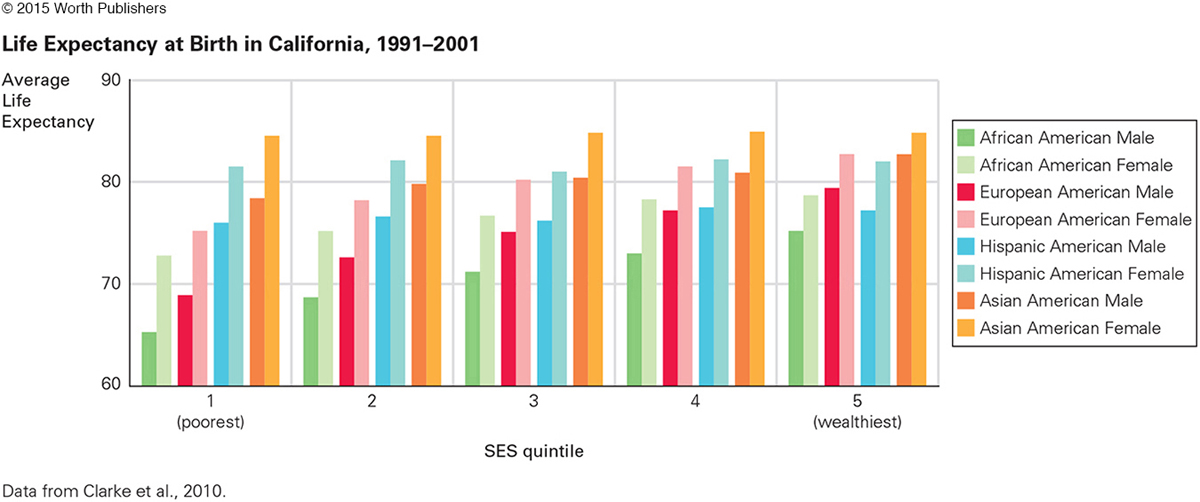

As you have also read, at each step some individuals break away from the usual path, but stratification theory contends that overcoming the liabilities of the past is increasingly difficult as life unfolds. By old age, people who have experienced poverty and prejudice all their lives almost never overcome their past, becoming healthy and wealthy (see Figure 15.3).

Stratification theory suggests that to help the aged, intervention can begin before birth. The fact that health problems result from a lifetime of stratification “suggests multiple intervention points at which disparities can be reduced” (Haas et al., 2012, p. 238).

Each stereotype adds to stratification and thus adds to the risk of problems, perhaps putting those who are female, non-

GENDER STRATIFICATION Irrational, gender-

In another example, the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics reported in 2013 that even though more old women live alone than old men, fewer old women are victims of every major type of crime. (Generally, rates of criminal victimization for both sexes fall with age, with less than half a percent of crime victims being over age 65.)

In another example of gender stratification, young women typically marry men a few years older and then outlive them. Especially in former years, many married women relied on their husbands to manage money. Thus, past gender stratification produced many old widows who were lonely, poor, and dependent for decades.

Longevity itself may result from lifelong gender stratification. Boys are taught to be stoic, repressing emotions and avoiding medical attention, which makes old men avoid doctors. In 2012 in the United States, twice as many men as women never saw a doctor (21 percent versus 11 percent) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2014). Thus, gender stratification may make men die too soon and women lonely for too long.

ETHNIC STRATIFICATION Remember that ethnic differences are sometimes codified as racial differences, with racial attitudes and experiences over a lifetime affecting many elders. As you remember from Chapter 12, racism causes weathering in African Americans, increasing allostatic load, shortening healthy life (Thrasher et al., 2012).

Past ethnic discrimination results in poverty for many minority families, itself a result of the quality of education, the health of neighborhoods, the salary of jobs.

Consider one detailed example, home ownership, which is a source of financial security for many seniors. Fifty years ago, stratification prevented most African Americans from buying homes. Laws then reduced housing discrimination, which meant that many African Americans finally bought homes. However, they often had new, and expensive, mortgages, so they suffered more than other groups in the foreclosure crisis that began in 2007. Is this a new example of an old story: stratification causing poverty (Saegert et al., 2011)?

A particular form of ethnic stratification affects immigrant elders. Most immigrants to North America come from non-

Thus, U.S. practices leave many older immigrants poor, lonely, and dependent on their children, who live in homes and apartments not designed for extended families. That may lead to two harmful family dynamics: unwelcome closeness in crowded, multigenerational homes, or distressing distance between elders and their descendants.

INCOME STRATIFICATION Finally, the most harmful effect of stratification may be financial, directly from poverty and then magnified by gender and ethnicity. As one reviewer explains, “[W]omen . . . are much more likely to live in households that fall below the federal poverty line. Black and Hispanic women are particularly vulnerable” (J. Jackson et al., 2011, p. 93).

Many of the poorest elderly never held jobs that paid into Social Security. Thus, an important source of income is absent. When ethnic discrimination affects employment opportunity, poverty in old age is particularly likely. Further, when money is scarce, that itself undercuts the ability to plan for the future (Haushofer & Fehr, 2014).

Income stratification is more apparent than either gender or ethnic stratification among the very old. Low-

AGE STRATIFICATION Ageism and age segregation affects life in many ways, including income and health. For example, seniority builds in the workplace, increasing income up to a certain point, and then employment stops, perhaps with a pension but never with as much income as before. People who are unskilled or temporary workers are particularly likely to be hurt by current old-

disengagement theory

The view that aging makes a person’s social sphere increasingly narrow, resulting in role relinquishment, withdrawal, and passivity.

The most controversial version of age stratification is disengagement theory (Cumming & Henry, 1961), which holds that as people age, four significant changes occur: Traditional roles become unavailable; the social circle shrinks; coworkers stop relying on them; and adult children turn away to focus on their own children. Meanwhile, older people become less mobile and less able to engage in social interaction.

According to this theory, disengagement is a mutual process, chosen by both adult generations. Thus, younger adult workers and parents disengage from the old, who themselves disengage, withdrawing from life’s action.

activity theory

The view that elderly people want and need to remain active in a variety of social spheres—

This theory provoked a storm of protest. Many gerontologists insisted that older people need and want new involvements. An opposing theory, activity theory, holds that the elderly seek to remain active with relatives, friends, and community groups. Activity theorists contended that if the elderly disengage, they do so unwillingly and suffer because of it (Kelly, 1993; Rosow, 1985).

Extensive research supports activity theory. Being active correlates with happiness, intelligence, and health. This is true at younger ages as well, but the correlation between activity and well-

Disengagement is more likely among those low in SES, which suggests it is another harmful outcome of past economic stratification (Clarke et al., 2011). Literally being active—

Both disengagement and activity theories need to be applied with caution, however. The positivity effect may mean that an older person disengages from emotional events that cause anger, regret, and sadness while actively enjoying other experiences. Current theories and research emphasize the variations in the lives of the aged, with neither disengagement nor activity theory always accurate (Johnson & Mutchler, 2014).

CRITIQUE OF STRATIFICATION THEORIES Contrary to all the preceding examples, might women, ethnic minorities, and low-

Both age-

Contrary to gender stratification, older women live longer and are happier than older men. They usually have closer relationships with friends and families, and grown children pay more attention to their aged mothers than their aged fathers. All this suggests that they might be less disadvantaged in late adulthood than they were as young women.

Similarly, cautionary data come from comparing the aged of various ethnic groups. Although in childhood and adulthood African Americans have poorer health and higher death rates than European Americans, that inequality disappears at about age 80 and then reverses. The average African American centenarian lives seven months longer than does the average European American one. Other minority ethnic groups do even better: Older Asian Americans have a several-

One scholar suggests that older African American women in the United States have the best mental health of all the race, age, and gender groups. He does not think “stratification systems such as gender, race and class” result in high risk for older adults. Instead “multiple minority statuses affect mental health in paradoxical ways . . . that refute triple jeopardy approaches” (Rosenfield, 2012, p. 1791).

THINK CRITICALLY: Could years of being at the top of the social hierarchy become a liability in old age?

One explanation for the race crossover in longevity is called selective survival—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.1

1. How does Erikson’s use of the word integrity differ from its usual meaning?

The word “integrity” is often used to mean honesty, but it also means a feeling of being whole, not scattered, and comfortable with oneself. In Erikson’s eighth stage, adults seek a feeling of wholeness and connectedness, feeling pride in their personal history. An inability to feel this would result in feelings of disconnectedness and despair.

Question 15.2

2. How does hoarding relate to self theory?

Older adults may begin to cling to possessions as they try to maintain a sense of self and of autonomy as they age. Things accumulate because possessions are part of self-

Question 15.3

3. What are the advantages of the positivity effect?

The positivity effect refers to elderly people’s tendency to perceive and remember positive events and to downplay negative ones. The positivity effect makes it easier for older adults to dismiss unpleasant or stressful events—

Question 15.4

4. What are the disadvantages of the positivity effect?

The positivity effect may explain why, in every nation and religion, older people tend to be more patriotic and devout than younger ones. They see their national history and religious beliefs in positive terms, and they are proud to be themselves. Of course, this same trait can keep them mired in their earlier prejudices—

Question 15.5

5. What are the problems with being female, according to stratification theory?

Irrational, gender-

Question 15.6

6. What are the problems with being male, according to stratification theory?

Boys are taught to be stoic, repressing emotions and avoiding medical attention, which could lead them to early death.

Question 15.7

7. How does immigrant status impair elderly people, according to stratification theory?

Most immigrants to North America come from non-

Question 15.8

8. Which type of stratification is most burdensome—

Economic stratification is the most harmful, and it is more apparent than either gender or ethnic stratification among the very old.

Question 15.9

9. How can disengagement be mutual?

According to the disengagement theory, younger adult workers and parents disengage from the old, who themselves disengage, withdrawing from life’s actions.

Question 15.10

10. If activity theory is correct, what does that suggest older adults should do?

They should remain active in a variety of social spheres, such as relatives, friends, and community groups. Being active correlates with happiness, intelligence, and health, according to research.

Question 15.11

11. What data support stratification theory, and what data refute it?

Life expectancy data from California for various ethnicities and both genders by SES provide evidence for ethnic and income stratification. Data comparing the aged of various ethnic groups refute it: Although in childhood and adulthood African Americans have poorer health and higher death rate than European Americans, that inequality disappears at about age 80 and then reverses. The average African American centenarian lives seven months longer than does the average European American one. Other minority ethnic groups do even better: Older Asian Americans have a several year advantage.