Heredity and Environment

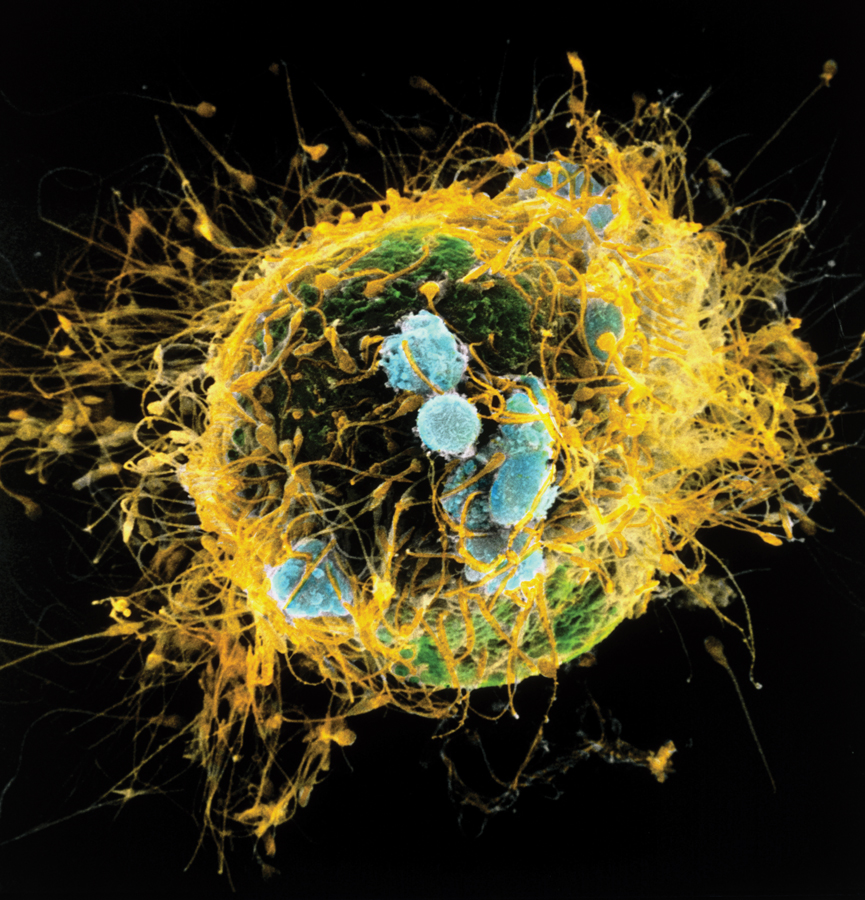

Observation Quiz In the chapter opening photograph, can you distinguish the Y sperm from the X sperm?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Probably not. The Y sperm are slightly smaller, which can be detected via scientific analysis (using such analysis, some cattle breeders raise only steers), but visual inspection, even magnified as in this photo, may be inaccurate. Further, these may all be Y sperm, as those may swim faster—but they may not necessarily be more successful at entering the ovum.

WHAT WILL YOU KNOW?

- What is the relationship between genes and chromosomes?

Each cell in the body contains 23 pairs of chromosomes. Chromosomes contain units of instructions called genes, with each gene located at a specific spot on a particular chromosome.

- Do sex differences result from chromosomes or culture?

Chromosomes determine one’s sex; females have two X chromosomes in the 23rd pair, whereas males have one X and one Y. However, the culture determines how those chromosomes are expressed.

- How can a child have genetic traits that are not obvious in either parent?

If the parents display dominant genetic traits in their phenotypes, they may carry unexpressed recessive traits that can be transmitted to their children. If a child inherits two copies of a recessive trait, that child will express that trait in his or her phenotype.

- If both parents are alcoholics, will their children be alcoholics too?

Genetic and cultural influences are “inexorably intertwined”; alcoholism has been shown to be the result of both nature and nurture. A genetic predisposition for alcoholism is not destiny, because culture is a pivotal factor in determining alcohol use.

- Why are some children born with Down syndrome, and what can be done for them?

Down syndrome occurs when a person inherits three copies of chromosome 21. There is no cure, but family context, educational efforts, and possibly medication can decrease the harm.

“She needs a special school. She cannot come back next year,” Elissa’s middle school principal told us.

Martin and I were stunned. Apparently the school staff thought that our wonderful daughter, bright and bubbly (Martin called her “frothy”), was learning-disabled. They had a specific phrase for it, “severely spatially disorganized.” We had noticed that she misplaced homework, got lost, left books at school, forgot where each class met on which day—but we thought that insignificant compared to her strengths in reading, analyzing, and friendship.

I knew the first lesson from genetics: Genes affect everything, not just physical appearance, diseases, and cognitive abilities, so I wondered whether Elissa had inherited her behavior patterns from us. Our desks were covered with papers, and our home had assorted objects everywhere. If we needed masking tape, or working scissors, or silver candle sticks, we had to search in several places. Could that be why we were oblivious to Elissa’s failings?

The second lesson from genetics is that nurture always matters. My husband and I had both learned to compensate for innate organizational weaknesses. Since he often got lost, Martin did not hesitate to ask strangers for directions; since I was prone to mislaying important documents, I kept my students’ papers in clearly marked folders at my office. Despite our genes, we both were successful; we thought Elissa was fine.

Once we recognized our daughter’s nature, we changed her nurture. We devoted much more attention to her homework and learning patterns; we hired a tutor who taught Elissa to list her homework assignments, check them off when done, put them carefully in her bag, and then take the bag to school. We reinforced those habits and did our part to change her social context. For instance, Martin attached her bus pass to her backpack; I wrote an impassioned letter telling the principal it would be unethical to expel her; Elissa herself began to study diligently when she realized she might need to leave her friends.

Success! Elissa aced her final exams, and the principal allowed her to return. She became a master organizer; 25 years later, she is an accomplished professional.

This chapter begins with nature and then emphasizes nurture. Throughout, we note some ethical and practical choices regarding the interaction of genes and environments. I hope you recognize the implications long before you have a seventh-grade daughter.