8.3 Language and Thought

Some of the differences between languages are obvious. They sound different. Written words look different. Another difference, however, is more subtle. One language may not have a word that corresponds to a word in another language. Research on emotion words illustrates this (Wierzbicka, 1999). Tahitian contains no word that corresponds to the English word “sad.” English has no word that corresponds to the Polish przykro, a negative emotion experienced when someone doesn’t display an expected amount of affection. German does not contain a word that corresponds precisely to the English word “emotion.”

These differences raise a big question: What is the relation between language and thought? When thinking about people’s feelings, do speakers of Tahitian, English, Polish, and German have the same types of thoughts, or do they have fundamentally different thoughts because their languages differ? If your language doesn’t contain a word corresponding to przykro, will you recognize the feelings of someone who did not receive an expected amount of affection?

The Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis

Preview Question

Question

Does language shape reality?

Does language shape reality?

Two twentieth-

If correct, this hypothesis is tremendously important for understanding human cultures. People who speak a different language than you may have a fundamentally different view of reality. Their perception of good and bad, right and wrong, may differ from yours.

Is the Sapir–

Such support, however, is relatively rare (Bloom & Keil, 2001). Other evidence contradicts the Sapir–

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

True or False?

According to the Sapir–

| A. |

| B. |

Embodied Cognition

Preview Question

Question

What does research on the Sapir–

What does research on the Sapir–

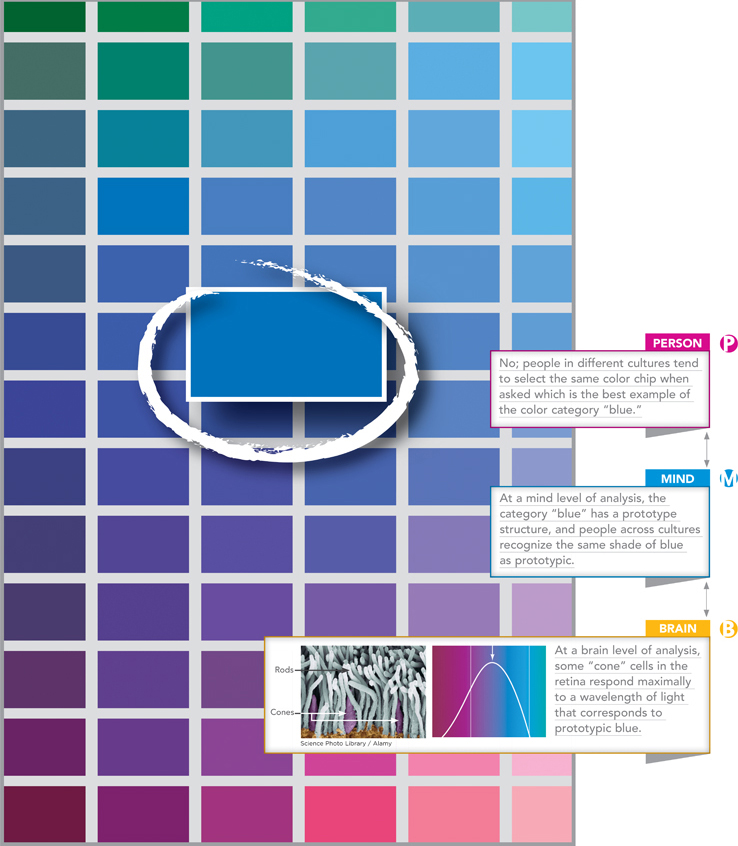

Brent Berlin and Paul Kay tested the Sapir–

However, they don’t. People who speak different languages think similarly about color. When Berlin and Kay showed participants color chips (Figure 8.7) and asked which were the best (i.e., the purest example of their general type of color), speakers of different languages identified the same colors. For example, speakers of a language with fewer than four color terms identified the same red, yellow, green, and blue chips as speakers of English. Later research confirmed these findings (Regier, Kay, & Cook, 2005). The results contradict the Sapir–

Do you know the names of every color in the room where you are now? Can you see the objects whose colors you can’t name?

The simplest explanation is that people’s thoughts about color are influenced by the workings of the visual system. The human visual system responds to some shades of color more strongly than to others (see Chapter 5). The visual system is universal. As a result, there are universal tendencies in the ways in which people categorize colors (Figure 8.8).

Berlin and Kay’s findings raise a broader point. Human thinking is embodied (see also Chapter 7). That is, when we think about abstract concepts, such as color, we use parts of the mind that evolved to relate our physical body to physical objects. Mental systems that originally evolved to help us perceive objects (to see and smell them) and to move our body toward or away from those objects are used in various forms of thinking (Barsalou, 1999; see also Chapter 6). Contrary to what Sapir and Whorf hypothesized, thinking is affected by more than just language.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 13

Research indicates that people’s thoughts about color are determined by the workings of the system, not by language. This contradicts the hypothesis but supports the idea that our thinking is embodied.

Thought and Language

Preview Question

Question

How do we know that thought influences language?

How do we know that thought influences language?

Not only does language influence thought, but the opposite is also true: Thought influences language. People often formulate an idea that they have trouble putting into words. The idea thus exists before language to express the idea is formulated.

Evidence that thoughts can precede language comes from the study of gesture (McNeill, 2005). Gestures are bodily movements, such as motions involving the arms, hands, and fingers that convey meaning. Sometimes you may struggle to put into words a meaning that you already have communicated by gesturing; for example, if you are trying to describe the complex movements of a dancer, you might start moving your hands and arms like the dancer did before you can formulate a sentence that describes the dancer’s movements in words. Some psychologists view the mind as engaged in back-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 14

Gestures are evidence that thought can precede language because (choose one):

| A. |

| B. |

TRY THIS!

The next section of this chapter discusses reasoning, judgment, and decision making. But before reading about these topics, experience some of them for yourself in this chapter’s Try This! activity. It presents some of the actual problems that researchers have used to discover how people think and make decisions. Go to www.pmbpsychology.com and complete the Try This! activity for Chapter 8 now. We’ll discuss it a little later in the chapter. ![]()