13.3 Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory

If you could travel back to 1880s Vienna, you could meet a young man destined to become psychology’s most famous figure: Sigmund Freud. In some ways, he would “look the part”: intelligent, well-

Circumstances changed his plans. Freud fell in love, needed to make money to get married, and thus sought a career more lucrative than that of research. He became a practicing physician (Jones, 1953)—a career move that had huge consequences. Freud’s work with patients launched his theory of personality, psychoanalytic theory (Freud, 1900, 1923)—also called a psychodynamic theory because it addresses the changing flow, or dynamics, of mental energy.

Freud’s patients presented him with a puzzle. They reported bodily symptoms that had no obvious physical cause; a patient might report paralysis of a hand, yet have no injury or illness that could cause paralysis. Freud concluded that the cause was not physical, but psychological. Memories of traumatic events buried deep in patients’ minds, he said, created physical symptoms.

Freud based this conclusion on his therapy experiences. With Freud’s encouragement, patients in therapy would talk about their problems. Gradually, after great effort, many would recall highly traumatic events they had not remembered for years (e.g., experiences of childhood sexual abuse). Recalling the long-

How easy do you suppose it is to forget a traumatic event from the past?

Freud later modified his conclusion, however. He judged that many of his patients’ long-

Freud’s ideas raise extraordinarily difficult questions. How could memories and fantasies cause physical symptoms? Why are traumatic memories so hard to recall? When people don’t recall such memories, where within the mind are they stored? Freud’s personality theory contained his answers.

Structure: Conscious and Unconscious Personality Systems

Preview Questions

Question

According to Freud, what are the three main structures of the mind?

According to Freud, what are the three main structures of the mind?

According to Freud’s “iceberg” metaphor, at what levels of consciousness does each structure of the mind reside?

According to Freud’s “iceberg” metaphor, at what levels of consciousness does each structure of the mind reside?

Freud proposed that personality is not a single, unitary part of the mind. Rather, personality consists of different parts—

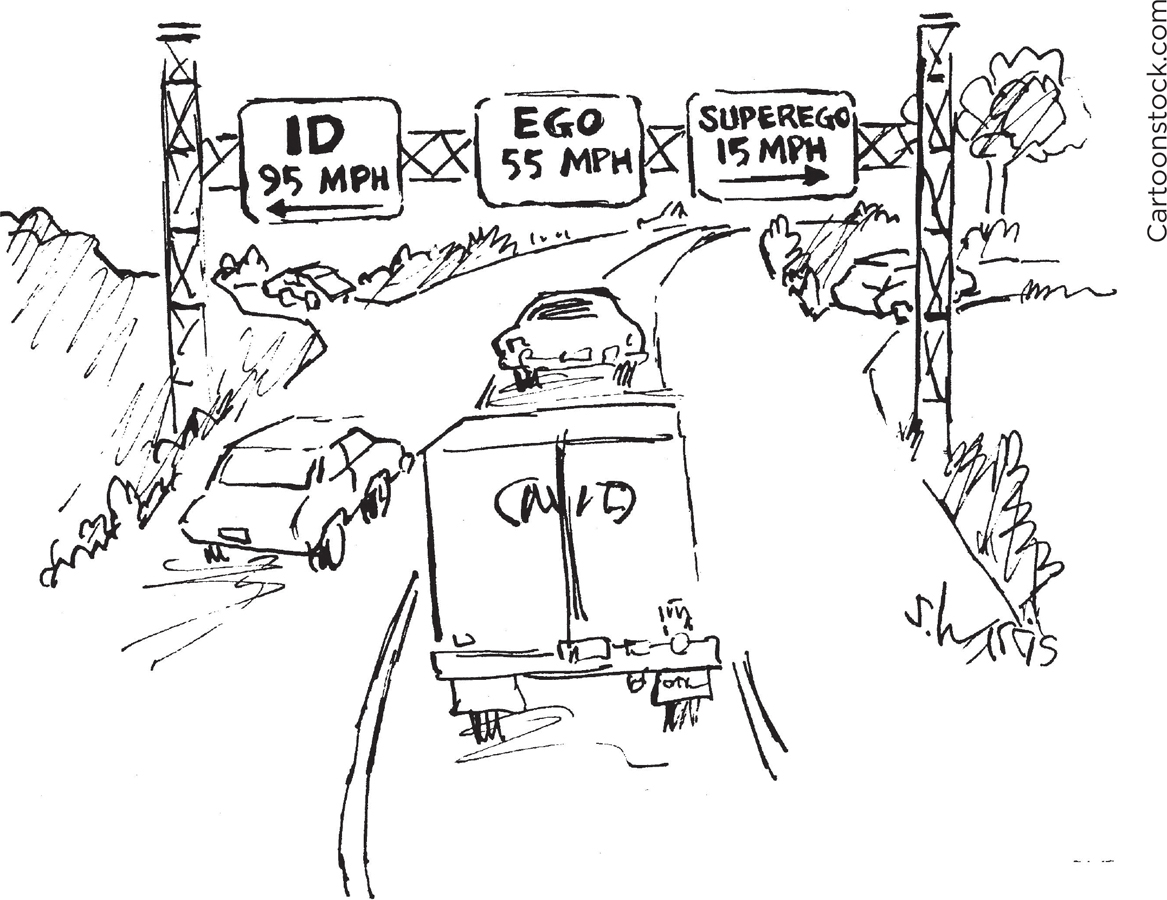

ID. The id is the personality system we are born with. It motivates people to satisfy basic bodily needs. The body needs food, and the id says, “Get it, now!” The body needs sex, and the id says, “Get it, now!” The id doesn’t do anything except say, “Get it, now!” The id operates according to the pleasure principle: It seeks immediate pleasure and the avoidance of pain.

The id thus is impulsive. It doesn’t care about what is “appropriate,” “acceptable,” and “moral.” It doesn’t even care what makes sense in the world of reality; a hungry infant will chew on both food and toys, even though the latter won’t reduce its hunger.

EGO. The second personality structure, the ego, is a mental system that balances the demands of the id with opportunities and constraints in the world of reality. The ego operates according to the reality principle: It tries to delay the id’s demands until there are circumstances in reality that enable the person to obtain pleasure while avoiding pain, including painful punishment that comes from breaking social rules.

To do this, the ego devises strategies. If a child wants a cookie, the ego’s strategy might be to sneak into the cookie jar when no one is looking. If a guy wants a date, his ego’s strategy is to tell the woman, “I’ll be getting a great, high-

The ego, according to Freud, is weaker than the id. Its strategies are feeble compared with the id’s impulsive desires. The ego is “like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse” (Freud, 1923, p. 15).

SUPEREGO. Do you ever have sudden pangs of guilt? Almost everyone does. Freud believed they’re generated by a third personality structure, the superego. The superego represents society’s moral and ethical rules—

Is there someone in your life who is the embodiment of the superego? Of the id?

In psychoanalytic theory, the superego develops as children interact with their parents. Parental commands (“Don’t hit”) gradually become internalized as superego rules (“Hitting is bad”).

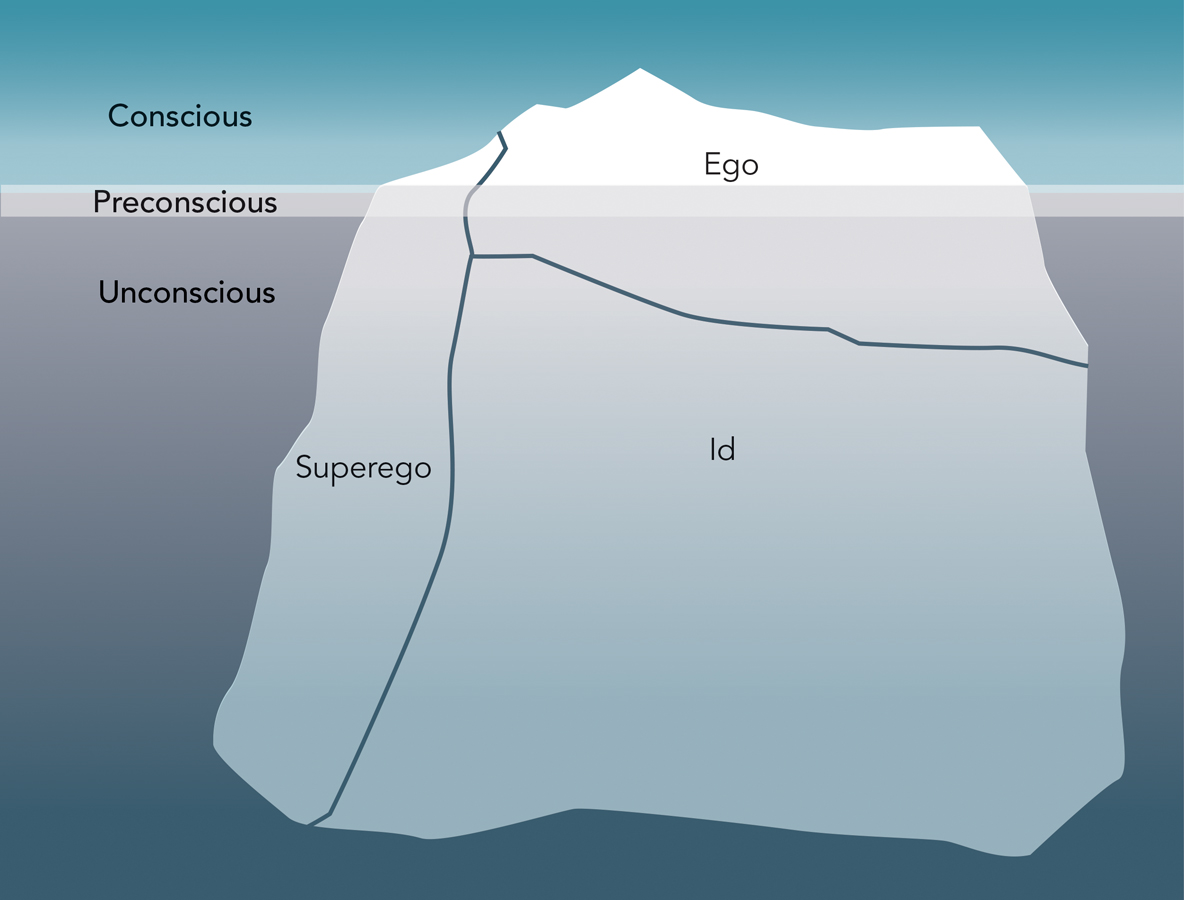

LEVELS OF CONSCIOUSNESS. Personality structures operate, according to psychodynamic theory, at different levels of consciousness. Consciousnes s refers to people’s awareness of mental contents and processes (Chapter 9). Levels of consciousness are variations in the degree to which people are aware of the contents of their mind.

Freud distinguished among three levels of consciousness. The conscious regions of mind contain the mental contents of which we are aware at a given moment. For instance, if you’re paying attention to the words on this page, then ideas about Freud’s theory of personality are in your conscious mind now. The preconscious contains ideas that you easily could bring to consciousness awareness if you wanted to. If, for example, someone asked for your phone number, you could think of it; before you were asked, the information was in your preconscious. Finally, the unconscious regions of mind contain ideas that you are not aware of and could not become aware of even if you wanted. Freud believed that a vast collection of painful memories is stored unconsciously—

Metaphorically, Freud suggested that the mind is like an iceberg: A small tip (consciousness) floats above the surface; a thin layer (the preconscious) is visible just below the surface; and the vast bulk of material (the unconscious) lurks below, out of sight (Figure 13.1).

The id is entirely unconscious. People cannot consciously “look into” their mind and directly see its desires. Both the ego and the superego are partly unconscious. Sometimes we aren’t aware of our ego strategies; you may really think that your ex is a terrible person, not recognizing that this conclusion is a strategy devised by the ego. Similarly, sometimes you may feel guilty without realizing how the superego has created this guilt. But sometimes, people are aware of the ego’s and superego’s contents. In general, Freud’s key insight—

CONNECTING TO THE CONSCIOUS AND UNCONSCIOUS MIND AND BRAIN

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 4

Match the personality structure on the left with the quote that exemplifies it on the right.

1. Id 2. Ego 3. Superego | “I want it now.” “I’m going to find a reasonable way to get that.” “I really shouldn’t have that.” |

Question 5

Match the type of thought on the left with the structure of the mind that stores it on the right.

1. The thoughts running through your mind right now 2. What you had for dinner last night 3. A traumatic memory from when you were a toddler | Unconscious Conscious Preconscious |

Process: Anxiety and Defense

Preview Questions

Question

What are the two basic types of mental energies according to Freud’s theory?

What are the two basic types of mental energies according to Freud’s theory?

According to Freud, how can experiences in childhood stages of development have lifelong effects?

According to Freud, how can experiences in childhood stages of development have lifelong effects?

How, according to Freud, do individuals keep themselves from experiencing excessive anxiety or expressing socially unacceptable behavior?

How, according to Freud, do individuals keep themselves from experiencing excessive anxiety or expressing socially unacceptable behavior?

The id, ego, and superego are stable personality structures. Their basic nature is consistent from one day of your life to the next. Let’s now look at the personality processes of psychoanalytic theory, which explain changes in psychological experience.

PSYCHODYNAMICS. Psychoanalytic theory views the mind as an energy system. Just as the physical energy of burning fuel powers an automobile engine, mental energy powers the mind. In the physical sciences, the changing physical energies of objects in motion are called dynamics. In psychoanalysis, mental energies are called psychodynamics. Psychodynamic processes are changes in mental energy that occur as energy flows from one personality structure to another or is directed to desired objects.

Freud proposed two types of mental energies: life energies (or a life instinct) and death energies (a death instinct):

Life energies motivate the preservation of life and reproduction. The life energies are primarily sexual; they motivate people to pursue sex and, more generally, to desire pleasurable, sensual activities.

Death energies oppose the life energies. Freud believed that humans possess an instinctive awareness of their mortality and a mental energy that motivates them to attain a final resting place (i.e., to die).

The life and death energies can power a wide variety of behavior. The ego directs them to diverse activities that are related symbolically to survival and sex or to death (see Chapter 11; also see Chapter 9 for Freud’s analysis of dreams and mental energy). Sexual energies power the efforts of an artist painting nudes or a musician composing sensual music. Death energies—

THINK ABOUT IT

Freud could not measure mental energies. How strong then is the evidence behind his theory?

Few contemporary psychologists endorse Freud’s precise ideas about the death instinct. Yet research does confirm his general intuition about the power of death-

In one test of the theory, researchers led participants to take a walk that either (1) passed through a cemetery or (2) did not pass through, or in sight of, a cemetery. All participants then overheard a conversation (in which the speaker was an experimental confederate; see Chapter 12) that exposed participants to a reminder of a cultural value, namely, helpfulness. Finally, participants encountered a stranger who needed help. People who had walked through the cemetery were more helpful (Gailliot et al., 2008); the reminder of death caused them to attend to the cultural norm of helpfulness. A meta-

PSYCHODYNAMIC DEVELOPMENT. In addition to identifying mental energies, Freud provided a theory of their development. He proposed that the id’s sexual energies develop in a series of steps, or stages. A psychosexual stage is a period in child development during which the child focuses on obtaining sensual gratification through a particular part of the body. The specific part of the body changes from one stage to another.

Freud identified five psychosexual stages (Table 13.1). In the oral stage (age 0 to 18 months), children seek gratification through the mouth by eating, sucking, and chewing. In the anal stage (18 months to 3½ years), they experience gratification from the release of tension that comes from the control and elimination of feces. In the phallic stage (3½ to 6 years), the source of gratification shifts to the genitals. At the end of the phallic stage, children enter a latency stage during which sexual desires are repressed into the unconscious until puberty. The genital stage, which starts at puberty, signals the reawakening of sexual desire.

13.1

| Freud’s Stages of Psychosexual Development | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Stage |

Age |

Adult Characteristics Associated with a Fixation |

|

Oral |

0 to 18 months |

Demanding, impatient; behaviors such as smoking, chewing gum |

|

Anal |

18 months to 3½ years |

Psychologically rigid; concerned about control and neatness |

|

Phallic |

3½ to 6 years |

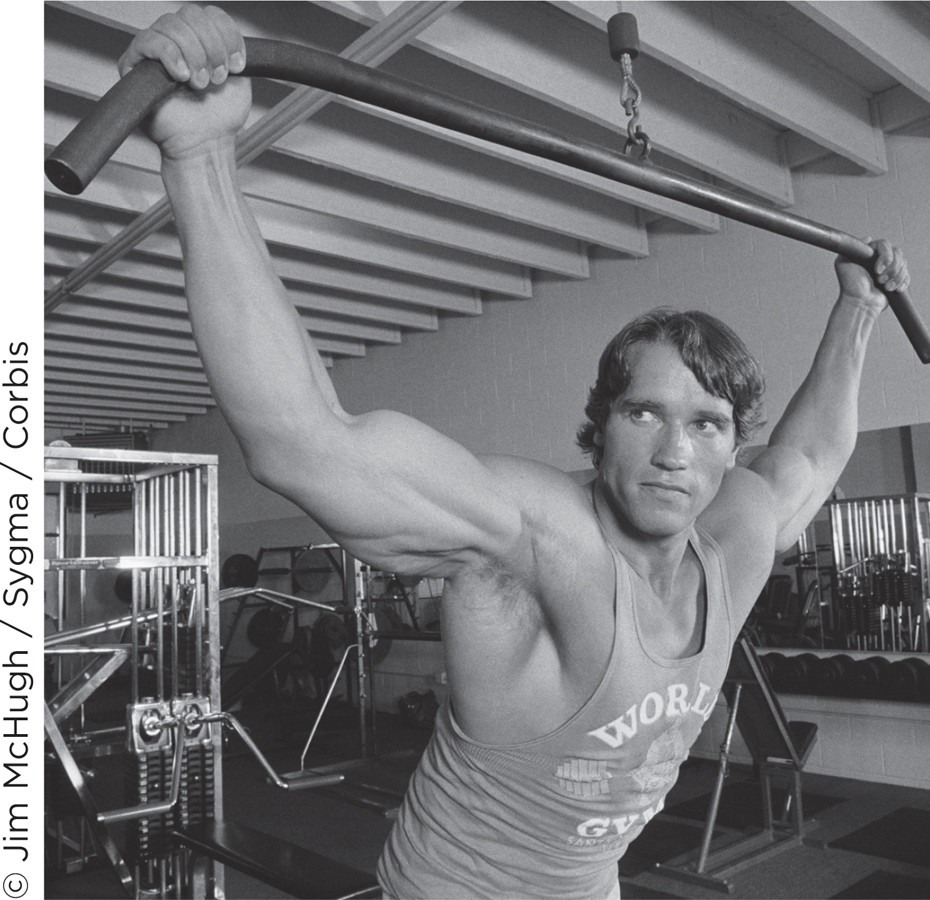

Male: competitive, “macho” Female: flirtatious |

|

Latency |

6 to 12 years |

None |

|

Genital |

12 years through adulthood |

If no fixations at an earlier stage, person can achieve emotionally mature sexual intimacy |

Freud claimed that the emotional themes of the childhood psychosexual stages are repeated throughout life. The adult who frequently smokes and chews gum is repeating themes from the oral stage. Adult love and sexual attraction to a romantic partner repeat the child’s first love and attraction, experienced toward the opposite-

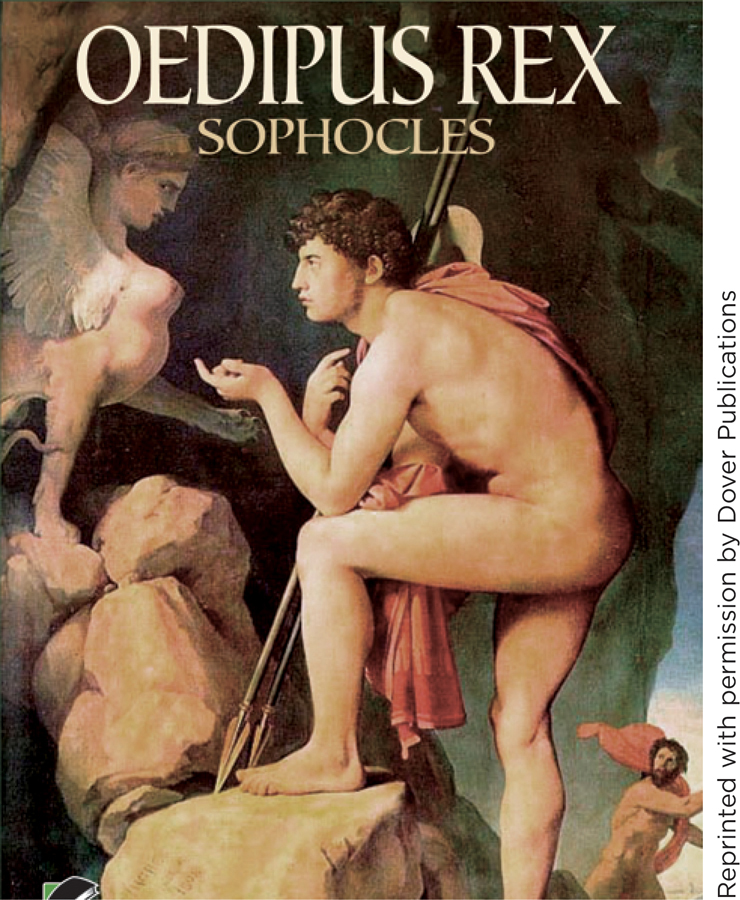

At each psychosexual stage, the child encounters prohibitions. At the oral stage, parents tell children to stop chewing on nonfood items. At the anal stage, they tell children to control the elimination of feces and use the bathroom. Each developmental stage, then, features a conflict: Biological urges conflict with social rules. Conflict is particularly intense at the phallic stage. At this stage, children experience sexual attraction toward the opposite-

THINK ABOUT IT

How can Freud’s theory be reconciled with principles of evolution? Wouldn’t it have been bad, from an evolutionary perspective, to be motivated to eliminate (kill off) a parent?

Freud believed that at the end of the first five years of life, an individual’s personality is set for the rest of his or her life. Do you agree?

Recall that children progress through the key psychosexual stages—

DEFENSE MECHANISMS. As you’ve just seen, the desires of the id conflict with the rules of society. The conflict, Freud explained, creates anxiety; people become anxious when they recognize that their desires conflict with moral rules. When this happens, defense mechanisms come to the rescue. A defense mechanism is a mental strategy devised by the ego to protect oneself against anxiety. Defense mechanisms reduce anxiety in two ways:

Block anxiety-

provoking ideas: The ego can protect against anxiety by blocking anxiety-provoking ideas from reaching consciousness. In the defense mechanism repression, for example, memories of highly traumatic experiences are kept in the unconscious and thereby are blocked from awareness. Distort anxiety-

provoking ideas: The ego can distort ideas so that, if they do reach consciousness, they arrive in a socially acceptable form. In sublimation, for example, an animalistic instinct toward sex or aggression is redirected to the service of a socially acceptable goal. For instance, a medical student might direct aggressive impulses toward the practice of surgery, where cutting into a patient releases aggressive energy.

Which of your daily activities, if any, can be construed as sublimation?

Freud believed that all people use defense mechanisms (Cameron & Rychlak, 1985). Table 13.2 lists a number of defense mechanisms that people frequently employ.

13.2

| Some Freudian Defense Mechanisms | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Defense Mechanism |

Definition |

Example |

|

Denial |

Failure to admit the existence or true nature of emotionally threatening information |

After buying a house in an earthquake- |

|

Repression |

Failure to remember anxiety- |

An adult does not recall an emotionally disturbing event from childhood. |

|

Rationalization |

Formulating a logical reason or excuse that hides one’s true motives or feelings |

After being turned down for a date, you say you weren’t really attracted to the person anyway. |

|

Projection |

Concluding that other people possess undesirable qualities that actually exist in oneself |

A hostile, aggressive person starts a fight with someone but blames the other person for initiating it. |

|

Reaction formation |

Expressing thoughts and behaviors that are the opposite of one’s true motives |

You are extremely friendly and generous toward someone you actually dislike. |

|

Sublimation |

Expressing socially undesirable motives in a socially acceptable form |

A person releases aggressive energy by taking a class in martial arts. |

|

Displacement |

Redirecting mental energy from a threatening target to an unrelated and less threatening target |

An employee angry at his or her boss yells at family members, thus redirecting the anger to them. |

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 6

True or False?

Freud suggested that a wide variety of behaviors are driven by two basic energies: a life energy and a death energy.

A. B. According to terror management theory, when people are reminded of their own imminent demise, they tend to increasingly adhere to cultural norms.

A. B. A fixation at any of the psychosexual stages of development only occurs when parents provide too little gratification at a given stage.

A. B. Gilbert, who is very consumed with his masculinity and with competition, is most likely fixated at the oral stage of psychosexual development.

A. B. The Oedipus complex is a constellation of feelings that arise during the anal stage of psychosexual development.

A. B. Defense mechanisms are strategies devised by the superego to satisfy the wishes of the ego within the constraints of the id.

A. B.

Assessment: Uncovering the Unconscious

Preview Questions

Question

According to Freud, why is the free association method the best way to assess personality?

According to Freud, why is the free association method the best way to assess personality?

What kinds of outcomes should projective tests be able to predict if they are valid? Do they?

What kinds of outcomes should projective tests be able to predict if they are valid? Do they?

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory complicates the task of personality assessment. A simple assessment strategy—

FREE ASSOCIATION METHOD. In the free association method, devised by Freud, psychologists encourage people to let their thoughts flow freely. They instruct people to say whatever comes to mind, even if it seems irrelevant or ridiculous. This procedure might sound odd, but Freud thought it was the best way to assess personality. He reasoned that the mind is like a machine. If a machine makes a sound (e.g., a banging in a car engine), something inside the machine must have caused it. The sound thus is a clue to the machine’s inner workings. Similarly, if an idea pops into someone’s mind, something inside the mind must have caused it. The flow of free associations thus provides clues to how the mind works.

Freud accepted a limitation of the free association method: It is slow. Patients may be in therapy for months before they associate to deeply significant material. (Freud’s therapy method is detailed in Chapter 15.) Others sought quicker methods and thus devised projective tests.

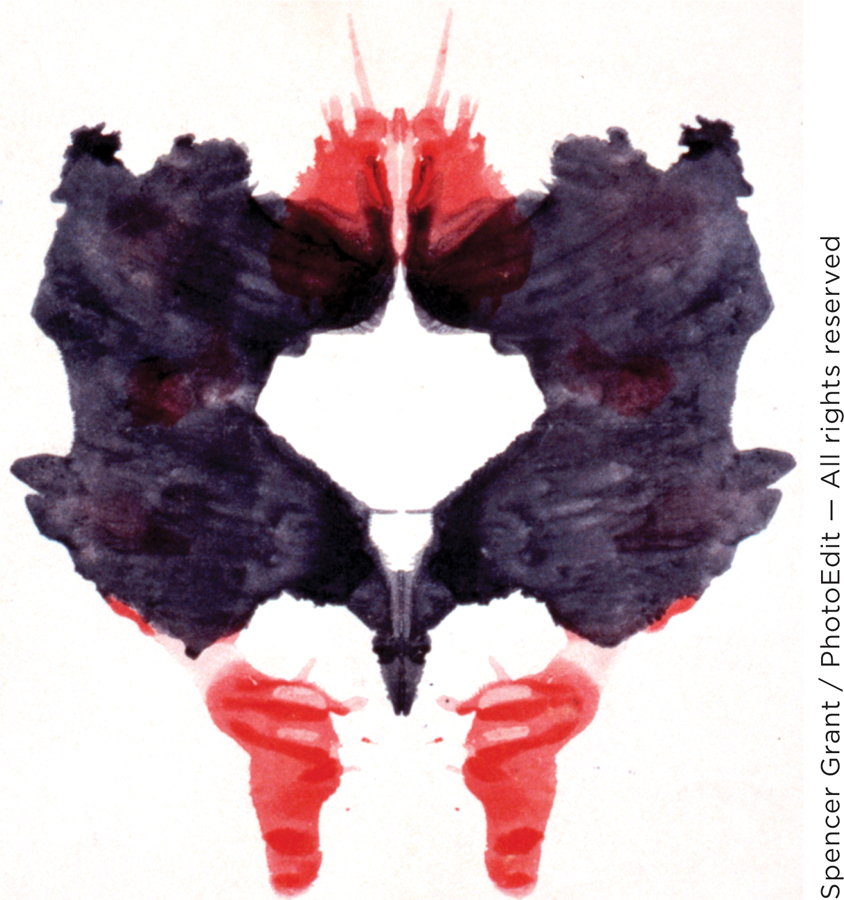

PROJECTIVE TESTS. A projective test is a personality assessment tool in which test items are ambiguous and psychologists are interested in how test takers interpret the ambiguity. For example, test takers might tell a story about people depicted in a drawing whose feelings and actions are unclear. The idea behind the tests is that when people interpret ambiguous items, they inevitably will draw on information in their own personalities. Elements of personality are thus “projected” onto the test.

A famous projective test is the Rorschach inkblot test (or, simply, the “Rorschach”), developed in 1921 by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach. The test items are symmetrical blobs of ink (Figure 13.2). Test takers say what the images look like to them, and explain their interpretations. Based on these responses, the psychologist usually tries to identify the test taker’s style of thinking: Did the test taker focus on the image as a whole or just a small part of it? Did his or her interpretation rely only on the inkblot image itself, or did it include imaginative flights of fantasy that went beyond the image?

The Rorschach is personality psychology’s most famous test. Unfortunately, it is more famous than accurate. Research shows that Rorschach test responses are poor predictors of important life outcomes, such as who might become depressed or who might perform well under high stress (Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000). Even when Rorschach responses do predict outcomes accurately, similar predictions often can be made through much simpler procedures (e.g., directly asking people if they tend to become depressed or perform well under stress; Mischel, 1968).

These negative results with the Rorschach reveal a limitation of the psychoanalytic approach. Freud and many of his followers neglected the principles of measurement and research design that make psychology scientific. One result of this neglect is their failure to develop efficient and accurate measures of personality.

The problem of psychoanalysis is not the body of theory that Freud left behind, but the fact that it never became a medical science. It never tried to test its ideas.

— Eric Kandel (quoted in Dreifus, 2012)

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 7

The following statements are incorrect. Explain why.

One of the reasons Freud so valued the free association method was that it was a relatively quick way to assess the contents of the unconscious.

A necessary feature of projective tests is that their images must be unambiguous in their meaning.

The value of the Rorschach is that it consistently predicts important outcomes such as depression.

a. This statement is incorrect because the free association method is a time-consuming method for assessing the contents of the unconscious. b. This statement is incorrect because a necessary feature of projective tests is that their images must be highly ambiguous in their meaning, so there is room for people to project their personalities onto them. c. This statement is incorrect because the Rorschach does not consistently predict important outcomes.

The Neo-Freudians

Preview Question

Question

How did the ideas of the neo-

How did the ideas of the neo-

Freud’s followers may have faltered when developing psychological tests. But they excelled at creating novel, insightful psychological theory. After Freud proposed his theory of personality, neo-

Adler (1927) felt that Freud underestimated the importance of social motives. People compare themselves to others in the social world—

Carl Jung (1939) judged that Freud underestimated the role of evolution. Specifically, Jung proposed that there are two different unconscious minds: (1) the one identified by Freud, which stores memories of events from one’s own life, and (2) another, overlooked by Freud, which stores ideas inherited from humans’ ancestral evolutionary past. Jung called this second unconscious mind the collective unconscious. The collective unconscious is a storehouse of mental images, symbols, and ideas that all humans inherit, in exactly the same form, thanks to their common evolutionary past. Throughout the history of our species, all humans experienced, for example, darkness (which is frightening), mothers (who are comforting), and wise older adults (who acquired wisdom during their long lives). Jung suggested that, as a result, concepts of darkness, mothers, and wise elders are stored in our collective unconscious. Without our even knowing it—

Erik Erikson (1950) worked to overcome two limitations in Freud’s theory of personality development:

Freud had focused only on development in early childhood. Erikson, by contrast, proposed a neo-

Freudian theory of developmental processes in childhood, adolescence, and early, middle, and older adulthood. Freud had focused on developmental processes that are internal to the person (sensual gratification focused on a part of the body). Erikson looked to the external world, proposing that development is a social process.

At each stage of development, people experience an emotional conflict, or “crisis,” that involves interactions between oneself and the social world. Infants, for example, face a crisis involving trust in others, on whom they are entirely dependent for survival. Table 13.3 summarizes Erikson’s theory.

13.3

| Erikson’s Stages of Development | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Stage of Life |

Approximate Age |

Predominant Psychological Crisis |

|

Infancy |

0 to 1 year |

Trust versus mistrust |

|

Early childhood |

1 to 3 years |

Feeling of autonomy versus doubt in one’s ability |

|

Preschool |

4 to 5 years |

Initiative (doing things on one’s own) versus guilt (about activities not valued by adults) |

|

School age |

6 to 12 years |

Industriousness and competence versus inferiority |

|

Adolescence |

13 to 19 years |

Clear sense of identity versus confusion |

|

Early childhood |

20 to 25 years |

Achieving intimacy versus superficial relationships and isolation |

|

Middle adulthood |

26 to 64 years |

Fulfilling, generative work versus stagnation |

|

Older adulthood |

65+ years |

Sense of order and meaning in life versus despair and regret |

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

Adler believed Freud ignored the fact that when we compare ourselves to others, we are often motivated to compensate for feelings of . Jung suggested that we inherit the contents of our unconscious from our common past. Erikson highlighted the idea that development is also a process that includes conflict between oneself and others at each stage.

Evaluation

Preview Question

Question

What disadvantages of Freud’s theory call into question its usefulness?

What disadvantages of Freud’s theory call into question its usefulness?

Freud’s theory of personality had immense impact. His insights revolutionized people’s view of human nature; the idea that most memories and feelings are unknown to the individual, buried in the unconscious, was startling. Beyond psychology, scholars in other fields—

How valuable, though, are Freud’s ideas as a scientific theory of personality? Freud, as you’ve seen, depicts personality as an energy system with three structures (id, ego, and superego) that regulate the flow of two types of energy (life/sex, death/aggression). In this model, much of mental life occurs outside of conscious awareness, and much of it is a struggle between biological urges and social rules. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this model?

An advantage is that it captures the complexity of personality. Mental life truly is a mix of conscious experiences and unconscious processes. People often do experience conflict within themselves and between personal desires and social rules. Freud’s theory is complex enough to address these aspects of human experience. Some other theories of personality are not.

Yet the complexity brings costs. The major cost is that elements of Freud’s theory are difficult—

A final limitation is that, in some respect, psychoanalytic theory is not complex enough. Does the mind contain only three main personality structures (id, ego, and superego)? Most contemporary psychologists don’t think so. As discussed elsewhere (especially Chapters 6 and 11), research suggests that the mind contains numerous mental systems that contribute to memory, thought, and motivation—

Such limitations motivated psychologists to develop alternative theories of psychoanalytic personality, as we’ll see next.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

On what bases can Freud’s psychoanalytic theory be criticized?

It lacks the tools for precisely and objectively measuring the structures of personality.

A. B. There are not enough structures specified to account for the full range of human behavior.

A. B. It treats people as if they are more complex than they actually are.

A. B.

TRY THIS!

Before you learn about the next theory of personality, take part in an activity that might lead you to learn something about yourself. Go to www.pmbpsychology.com and complete the Try This! activity for Chapter 13. It’s a personality assessment that you will learn about in the next section of the chapter—![]()