16.1 Psychotic Disorders and Schizophrenia

Preview Questions

Question

What does it mean to suffer from a psychotic disorder?

What does it mean to suffer from a psychotic disorder?

How prevalent is schizophrenia?

How prevalent is schizophrenia?

The previous chapter focused on depressive and anxiety disorders. Those disorders can disrupt people’s lives, yet they generally leave two psychological qualities intact. One is that people are in touch with reality. For example, a socially anxious person’s level of worry about social relationships may be excessive, but the relationships really do exist. Another quality is that thinking is organized logically. A depressed person may say, “I just feel I’m wasting everyone’s time. No one can help me” (see Chapter 15), but is unlikely to say, “I have a sort of silver bullet which held me by my leg, that one cannot jump in, where one wants, and that ends beautifully like the stars” (McKenna & Oh, 2005, p. 2)—a disorganized jumble of ideas.

In psychotic disorders, people lose these basic mental abilities. Psychotic disorders are psychological disorders whose core symptoms are that people’s thoughts and actions are disorganized and their thinking loses touch with reality; people see and worry about things that do not exist (Heckers et al., 2013).

A particularly severe psychotic disorder, which we will focus on first, is schizophrenia. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, discussed in Chapter 15) defines schizophrenia as a disorder in which people exhibit multiple psychotic symptoms (detailed below) for a period of at least one month. Schizophrenia is prevalent globally. A meta-

Let’s first learn about schizophrenia at a person level of analysis. We’ll examine symptoms that haunt the lives of people with schizophrenia, as well as the illness’s typical development across the course of people’s lives. Next, we’ll move “down” to mind and brain levels of analysis to show how schizophrenia affects information processing in the mind and physiological functioning in the brain. The study of mind and brain, as you’ll see, helps to explain the symptoms experienced by people with schizophrenia. Finally, you’ll learn how mental health professionals treat this mental illness.

People with Schizophrenia

Preview Questions

Question

What are the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia?

What are the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia?

What cognitive impairments do people with schizophrenia experience?

What cognitive impairments do people with schizophrenia experience?

People with schizophrenia face exceptional challenges. Schizophrenia symptoms severely disrupt their experience of the world and their sense of self (Estroff, 1989). The symptoms are of three types (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009):

Positive symptoms: Mental events that are experienced by people with schizophrenia but rarely by others (e.g., hallucinations). The word “positive” here indicates the presence, rather than absence, of a symptom; a positive symptom adds something unwanted to one’s life.

- Page 706

Negative symptoms: The absence, among people with schizophrenia, of desirable psychological experiences common among most people (e.g., the experience of enjoying social events). The word “negative” indicates an absence of a desirable quality; negative symptoms subtract something desirable from one’s life.

Cognitive impairments: Reduced ability to perform everyday thinking tasks (e.g., an inability to concentrate on information).

Let’s examine these in detail, beginning with positive symptoms.

POSITIVE SYMPTOMS. One positive symptom of schizophrenia is delusional beliefs, which are personal convictions that contradict known facts about the world but that a person clings to even when faced with conflicting evidence (Heckers et al., 2013). You read some delusional beliefs in the quotes above. The idea that one’s family has been replaced by androids or that one is receiving messages from the CIA through the TV is typical of the delusional beliefs experienced by people with schizophrenia (Elgie et al., 2005). Such beliefs are so bizarre that you can’t help but wonder how anyone could take them seriously. Yet, to people with schizophrenia, they are vivid, compelling, and convincing. Some common delusional beliefs are somatic delusions (e.g., believing that one has been injured, is ill, or has been poisoned) and delusions of grandeur (believing one has special abilities or powers; Tateyama et al., 1998).

A second positive symptom of schizophrenia is hallucination. Hallucinations are experiences—

Some people with schizophrenia experience delusions and hallucinations, yet otherwise retain their normal thinking abilities. For example, when they express strange beliefs (e.g., “The demon is telling me what to do”), they do so in sentences that are organized logically. But others with the disease suffer a third positive symptom of schizophrenia: disorganized thinking. In disorganized thinking, people cannot structure their thoughts and spoken words in a manner consistent with standard rules of language use. Their thoughts are garbled and unintelligible.

Sometimes disorganized thinking is evident in sentence-

“I’m so scared I could tell you that picture’s got a headache.”

“Can you tell me more about that?” the interviewer asks.

“When a sperm and an egg go together to make a baby, only one sperm goes up the egg and when they touch there are two contact points touched before the other two then it’s carried up in the air. When they fuse it’s like nuclear fusion except it’s human fusion. There’s a mass loss of the proton. When heat abstraction goes up in the electron, spins around, comes back down into the proton to form the mind. And the mind could be reduced to one atom.”

—Neuroslicer (2007, April 18)

It’s not merely that the content of the person’s beliefs is bizarre (e.g., “picture’s got a headache”). In addition, the sentence-

Disorganized thinking can also occur at the level of sentences and individual words. Patients’ sentences may be schizophrenic word salads: seemingly random jumbles of words that are meaningless to listeners. When talking to someone with schizophrenia, you may hear sentences such as, “Tramway flogging into my question, are you why is it thirty letters down under peanut butter, what is it” (an example frequently cited online).

A final positive symptom of schizophrenia is disorders of motor movement (Arango & Carpenter, 2011). Patients may display odd mannerisms, such as a strange grimace on their face. Others engage in repeated movements, such as spinning a lock of hair over and over again. Still others exhibit catatonia, which is a lack of motor movement. Some people with schizophrenia display little movement throughout the day and thus appear withdrawn from the outside world. “No movement from me,” one writes. “It’s as if I was an old oak tree, the blank stare, the silent face” (www.schizophrenia.com posting).

NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia consist of emotional and behavioral deficits (Kirkpatrick et al., 1989). People with schizophrenia lack emotional experiences enjoyed by others and fail to engage in valuable social behaviors. These deficits in emotion and behavior reduce schizophrenic individuals’ overall sense of well-

One negative symptom is flat affect (pronounced AFF-

Another negative symptom is a lack of interest in social activities. Normally, people find some daily activities interesting. You might look forward to lunch, or meeting friends, or shopping, or playing video games—

People with schizophrenia often are well aware of this neglect: “Lately I’ve noticed that my personal hygiene has been (expletive),” one person writes. “I only shower once every two weeks, I don’t shave my face, I just don’t care how I look anymore” (www.schizophrenia.com posting). They also may possess insight into why they lack motivation for personal care: “When we discover that our futures are impacted by an incurable disease, we give up on it.”

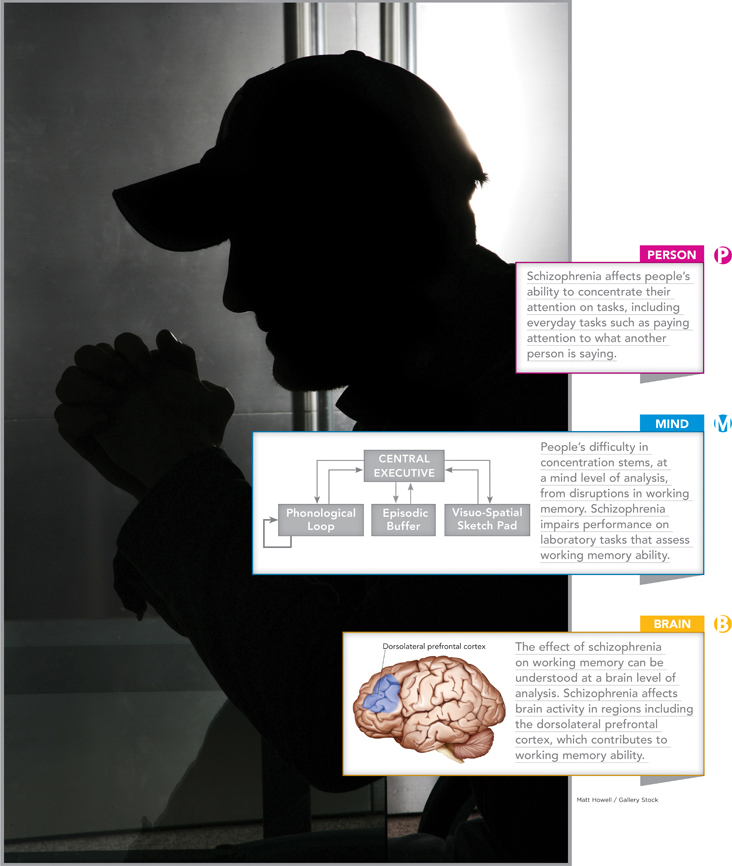

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENTS. On top of the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, individuals with the disease also experience cognitive impairments, which, as noted previously, are reduced abilities to execute mental skills that are simple for most people (Kuperberg & Heckers, 2000). We’ll look at three, which involve concentration, memory, and social cognition —that is, thinking about other people and social interactions (see Chapter 12).

Concentration: Many people with schizophrenia have difficulty concentrating their attention on tasks (Hilti et al., 2010). This includes everyday tasks such as attending to what a person is saying. They often are painfully aware of this problem. “Do you [i.e., like me] have trouble understanding/reading what people say to you?” one patient asks. “My head is currently scrambled, noisy, can’t concentrate and scared people will talk to me because I can’t understand much” (www.schizophrenia.com posting). “I have TERRIBLE problems with this,” another writes. “[I] forget what I was saying or what the conversation is about midway through it. It is a horrible, awful symptom of the disease” (www.schizophrenia.com posting).

Remembering : People with schizophrenia do not lose all of their memory ability; rather, the illness impairs their ability to remember certain types of material. One is visual information; people with schizophrenia perform relatively poorly when trying to recall images or the spatial location of objects (Palmer et al., 2010). Another is episodic memory (see Chapter 6), or memory for personal experiences. Their episodic memory for emotional experiences is particularly poor (Herbener, 2008). These memory deficits degrade quality of life—

in particular, because it makes it difficult to plan new activities (Herbener, 2008). People often make plans by asking themselves, “What would I like to do today?” and consulting memories of experiences that were enjoyed in the past. People with schizophrenia who cannot easily remember past activities thus have trouble making plans. As a result, they engage in fewer professional and social activities, which further reduces their quality of life. How well do you know your way around a keyboard? This largely depends on your ability to recall spatial location.

Social cognition: People with schizophrenia experience a number of social-

cognitive problems. They err when thinking about the reasons behind other people’s behavior. For example, if someone fails to return a phone call of theirs quickly, they may think, wrongly, that the other person is expressing hostility toward them (Green et al., 2005). They also have lower social- cognitive skills, with less ability to initiate conversation and maintain eye contact. The skill deficits make it difficult for them to succeed in the workplace, where many jobs require skillful social behavior (Dickinson, Bellack, & Gold, 2007). Finally, individuals with schizophrenia may display inappropriate social emotions (Cole & Hall, 2008). They have trouble controlling their emotions and matching emotional expressions to their present circumstances. “The other day in group [therapy],” one patient relates, “the counselor asked us … have we bursted out laughing at inappropriate times? I told him I had and while I was telling him the story I was laughing. It was sad because it had to do with my principal dying while I was in high school” (www.schizophrenia.com posting).

Table 16.1 summarizes the range of symptoms—

16.1

| Symptoms of Schizophrenia | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Positive Symptoms |

Negative Symptoms |

Cognitive Impairment |

|

Delusional beliefs |

Flat affect |

Difficulty concentrating |

|

Hallucinations |

Lack of pleasure and interest in activities |

Difficulty remembering, especially personal experiences and emotions |

|

Disorganized thinking |

|

Impaired social cognition |

TRY THIS!

Now that you have read about the experiences of people with schizophrenia, it’s time for you to also see and hear about them. Go to www.pmbpsychology.com now for this chapter’s Try This! activity. ![]()

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 1

Classify the following statements as illustrating either positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

“I just can’t seem to motivate myself to start a new project.”

“If you come in from the rain, use a laser pointer to run the bookstore.”

“I know you’re supposed to talk to people at parties, but I just don’t care to.”

“I can’t believe you don’t see the yellow rabbit standing over there.”

Choices a and c are examples of negative symptoms of schizophrenia; choices b and d are examples of positive symptoms.

Question 2

Jean, a person with schizophrenia, noticed that a man sitting across from her in the train station was smiling at her. Though the other person meant to convey friendliness, Jean thought he was mocking her. Of the three types of cognitive impairments described in this section (concentration, memory, and social cognition), which does Jean’s misinterpretation best exemplify? Briefly explain.

Schizophrenia and Information Processing

Preview Questions

Question

Why are the thoughts of people with schizophrenia so disorganized?

Why are the thoughts of people with schizophrenia so disorganized?

Why are people with schizophrenia so poor at making decisions?

Why are people with schizophrenia so poor at making decisions?

Why do people with schizophrenia experience this broad range of symptoms? Some answers come from research on how the illness affects information-

WORKING MEMORY. Working memory (see Chapter 6) is the mental system you use to store information in mind for brief periods (e.g., a phone number you keep in mind until you have time to write it down), to manipulate stored information (e.g., adding up a set of digits), and, importantly, to control your own mental activities. Working memory contains a “central executive” that people use to focus attention on tasks. When you concentrate on solving a problem while avoiding distractions from nearby sounds and sights, you’re employing the central executive component of your working memory system.

In schizophrenia, working memory is impaired (Barch, 2005). Individuals with schizophrenia perform less well than others on laboratory tasks that assess working memory ability (Barch, 2005). This working memory impairment helps to explain symptoms experienced by people with schizophrenia, discussed earlier, such as disorganized thinking (where words and sentences are not connected logically). Working memory is the “executive” mental system that enables people to organize their thoughts. Breakdowns in this component of the mind thus contribute to a positive symptom of schizophrenia, disorganized thought.

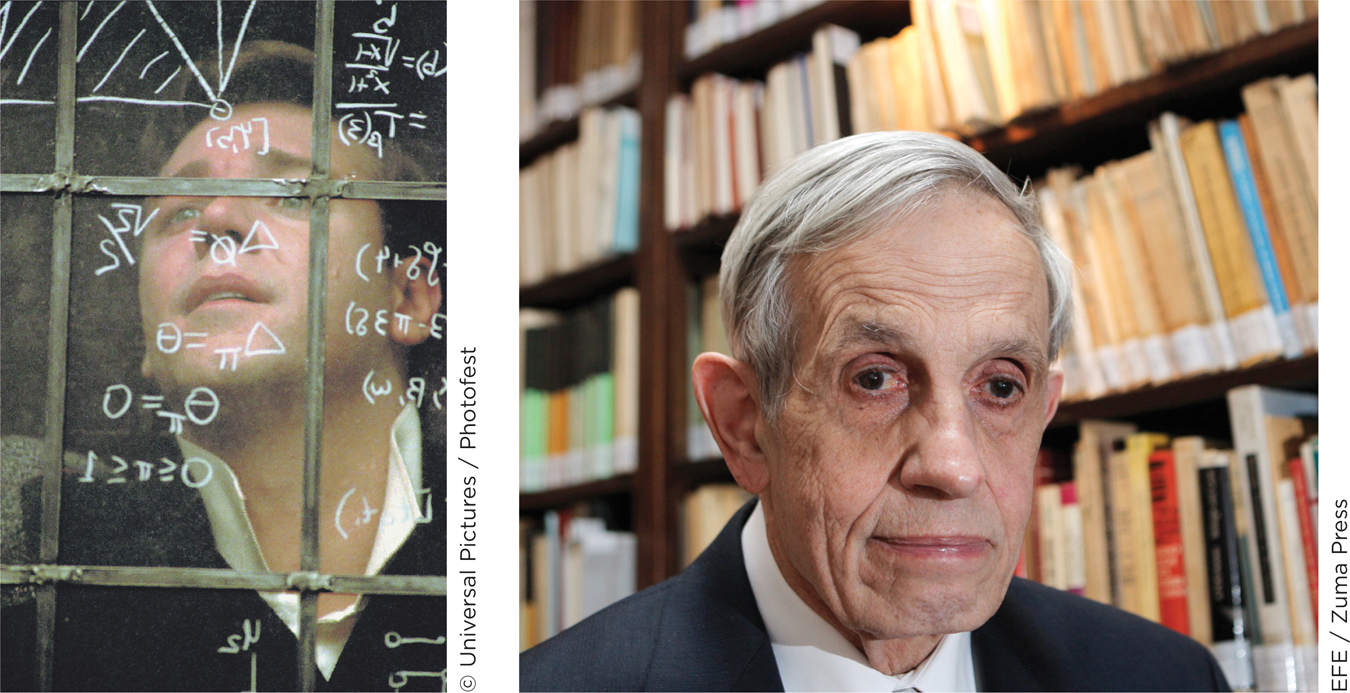

CONNECTING TO THINKING, EMOTION, AND THE BRAIN

An additional information-

EMOTION AND DECISION MAKING. In addition to affecting working memory, schizophrenia impairs mental systems that are needed for decision making. These systems involve both thinking and emotion. When people who are not affected by schizophrenia make decisions, their emotions often improve the quality of their decision making (see Chapter 10). Specifically, negative emotions experienced after bad decisions help people avoid making those same poor decisions in the future. Key evidence of this comes from research where people played a gambling task in which participants’ emotional reactions and decisions were recorded. Negative emotions after bad gambling decisions helped people improve the decisions they made on future gambles (Bechara et al., 1994).

What happens when people with schizophrenia play this gambling game? Unlike most others, they show little improvement across trials of the task (Shurman, Horan, & Nuechterlein, 2005). Even after big gambling losses, schizophrenic patients do not have the emotion-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 3

Answer the following questions about impairment in schizophrenia.

How does an impairment in working memory lead to the disorganized thinking seen in many people with schizophrenia?

How does impairment in the functioning of emotions lead to the decision-

making impairments observed in many people with schizophrenia? a. Working memory ability includes the ability to store information in one’s mind for brief periods, to manipulate that information, and to control one’s thinking. Impairments in any of these abilities would make it difficult to think in an organized manner. b. Emotions enable us to learn from our mistakes to make better decisions; an impairment in emotional functioning can thus disrupt this process and impair decision making.

Schizophrenia and the Brain

Preview Questions

Question

How can the delusional thinking displayed by people with schizophrenia be explained at the mind and brain levels of analysis?

How can the delusional thinking displayed by people with schizophrenia be explained at the mind and brain levels of analysis?

How are the brains of people with schizophrenia different from those without the disorder?

How are the brains of people with schizophrenia different from those without the disorder?

We’ve now seen what life is like for people with schizophrenia. They experience delusions and flat affect, and they have difficulty focusing on tasks and planning daily events. We’ve also seen how schizophrenia affects information-

Let’s now move to a biological level of analysis. How does schizophrenia affect the brain and how do these biological effects explain the psychological ones?

As discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, the brain contains both neurons (the cells of the brain) and neurotransmitters (the chemical substances through which neurons communicate). We’ll look at both, starting with the role of a specific neurotransmitter, dopamine, in schizophrenia.

DOPAMINE. The brain contains a variety of neurotransmitters. When searching for biochemical bases of schizophrenia, then, two questions arise: Which neurotransmitter is most central to schizophrenia? And why do high or low levels of that neurotransmitter cause schizophrenic symptoms?

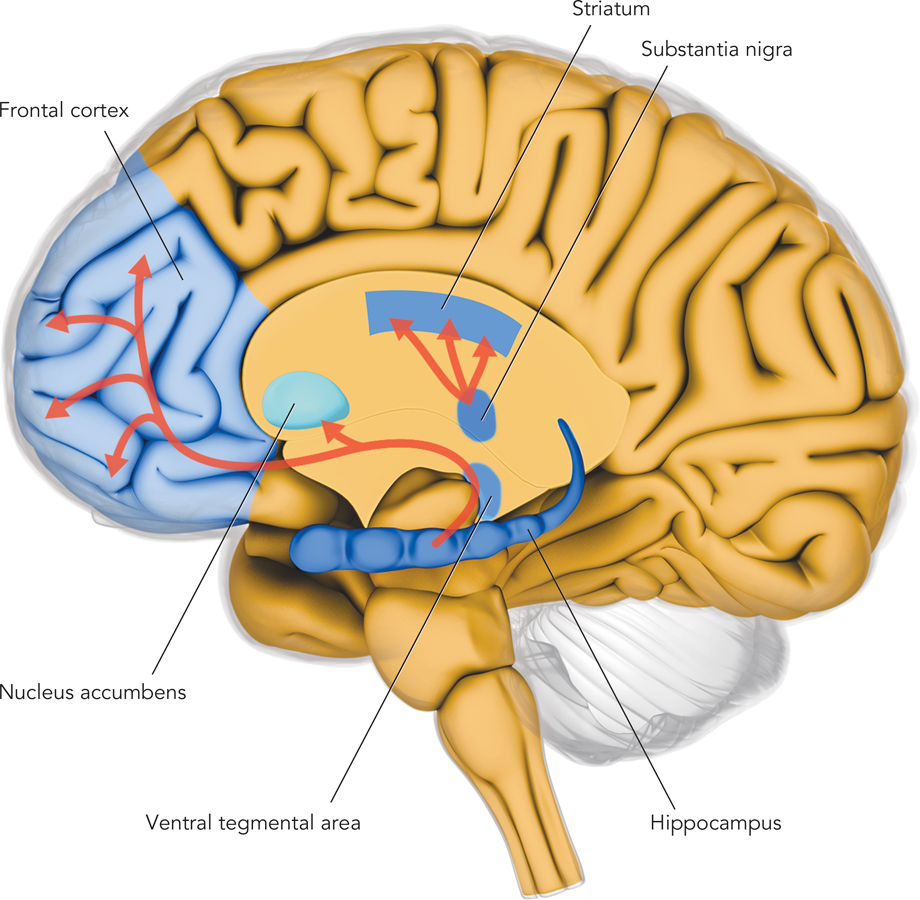

Most researchers agree that the answer to the first question is dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter found in multiple regions of the brain (Figure 16.1). Thanks to its widespread presence, it can affect multiple aspects of mental life.

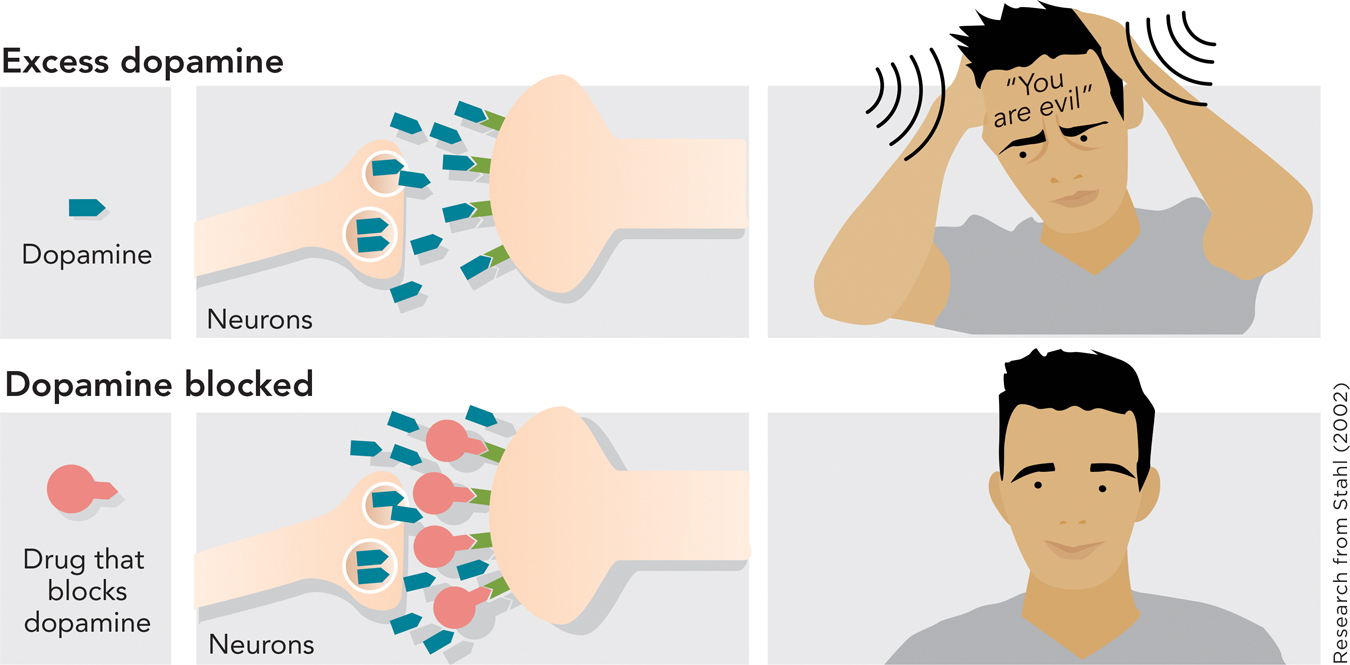

More than half a century ago, researchers discovered that dopamine and schizophrenia were linked. The discovery originated with an unexpected finding: Some drugs originally designed to treat other medical problems were found to reduce symptoms of schizophrenia (Valenstein, 1998). The drugs, it turned out, were those that blocked the neuron-

Research has provided support for the dopamine hypothesis. For example, individuals with schizophrenia have relatively high levels of dopamine in subcortical regions of their brains; they may also have excess dopamine receptors, the molecules on the surface of neurons that receive dopamine signals (Kapur, 2003).

At a clinical level the doctor–

—Kapur (2003, p. 13)

THINK ABOUT IT

If people with schizophrenia have abnormal levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine in their brains, does this prove that dopamine caused them to develop schizophrenia? You should be saying no by now! It might be that some other factor caused schizophrenia to develop and that the stress of living with schizophrenia affected neurotransmitter levels in the brain.

FROM DOPAMINE TO DELUSIONS. Two key facts about schizophrenia, then, are that (1) people have delusional beliefs and (2) the brain has excess dopamine. How can we put together these person-

One theory connects the person-

What does this have to do with schizophrenia? In schizophrenia, excess dopamine causes even trivial stimuli—

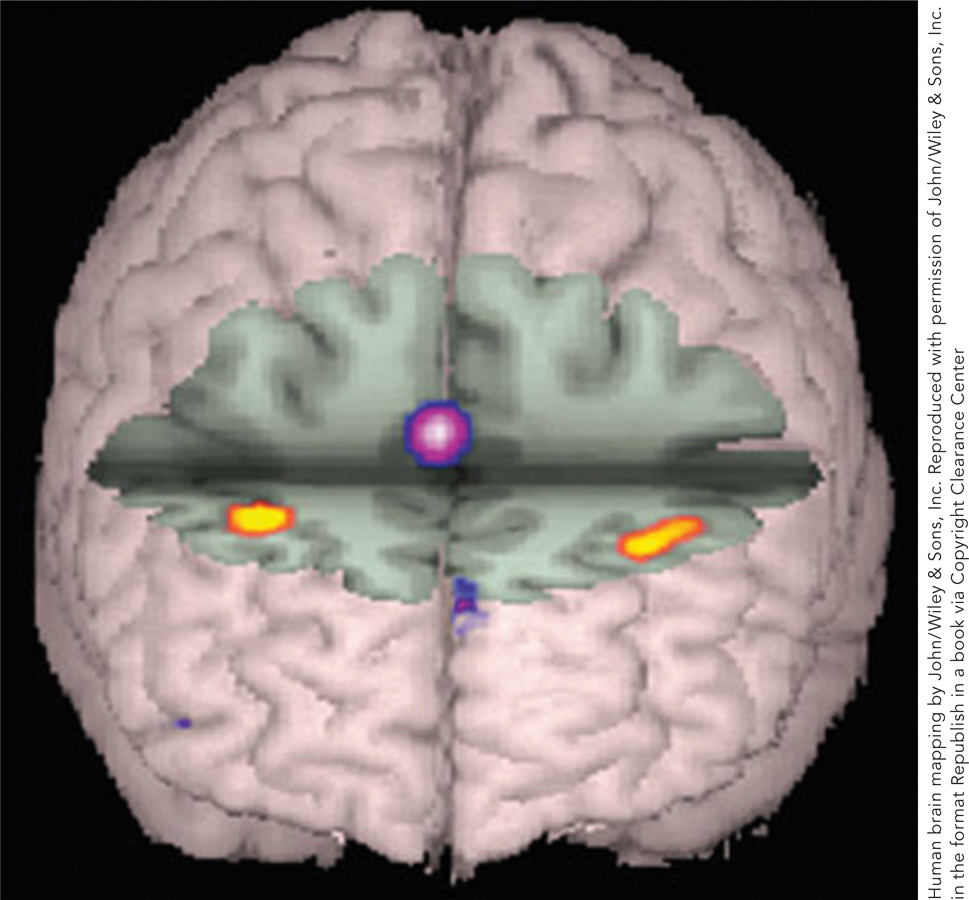

BRAIN STRUCTURES AND SCHIZOPHRENIA. Let’s now turn from neurotransmitters to brain structures, to examine activity in the various parts of the brain, each of which contains millions of neurons (Chapter 3).

Which brain structures does schizophrenia affect? You name it—

One brain area is enlarged, rather than reduced, in people with schizophrenia: the brain’s ventricles (Palmer, Dawes, & Heaton, 2009). The ventricles are spaces in the brain filled with a fluid that supports the brain’s functioning. These spaces do not contain neurons. Larger ventricles mean that a smaller percentage of the brain’s overall volume contains the neurons that power thinking.

Although schizophrenia affects the whole brain, some brain regions are likely to be more central to the disease than others. How could you find them? The search has benefited from a strategy you see often in this book: using research on the mind to guide research on the brain. Earlier, you saw that one aspect of mind that schizophrenia strongly impairs is working memory. This mind-

It is lower in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain structure known to be key to working memory (Curtis & D’Esposito, 2003).

It is higher in the anterior cingulate, a brain region known to be active when people detect errors in their performance. The lower task performance caused by reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex (point #1) heightens people’s sensitivity to errors they are making (Glahn et al., 2005).

Once again, one can connect these brain-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 4

Which of the following statements about dopamine and delusions are true?

According to the dopamine hypothesis, positive symptoms are the result of too little dopamine-

based communication in subcortical regions of the brain, and negative symptoms are the result of too much of this activity in the brain’s cortex. A. B. Excess dopamine can cause lots of stimuli to grab attention, even when those stimuli are not important.

A. B. People with schizophrenia may experience delusions because they try to invent explanations for the overwhelming amount of stimuli that grabs their attention.

A. B. In individuals with schizophrenia, brain volume is larger and ventricles are reduced in size.

A. B. When people with schizophrenia perform an activity that tasks working memory capacity, they experience higher activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, an area known to be active during tasks that require working memory capacity, than people without schizophrenia.

A. B. When people with schizophrenia perform an activity that tasks working memory capacity, they experience lower activity in the anterior cingulate, an area known to be active when people detect their own errors.

A. B.

The Development of Schizophrenia

Preview Questions

Question

Do genes alone determine whether someone will develop schizophrenia?

Do genes alone determine whether someone will develop schizophrenia?

When does schizophrenia first develop?

When does schizophrenia first develop?

Now that we’ve seen how schizophrenia affects people, the mind, and the brain, let’s look at how it develops. One factor to consider in the development of the disease is genetics (Riley, 2011).

GENES AND THE ENVIRONMENT. When asking about genes and the development of schizophrenia, two scientific questions require answers: (1) Do genes have an effect? (2) If so, why? Which genes are important, and how do they contribute to the disease’s development?

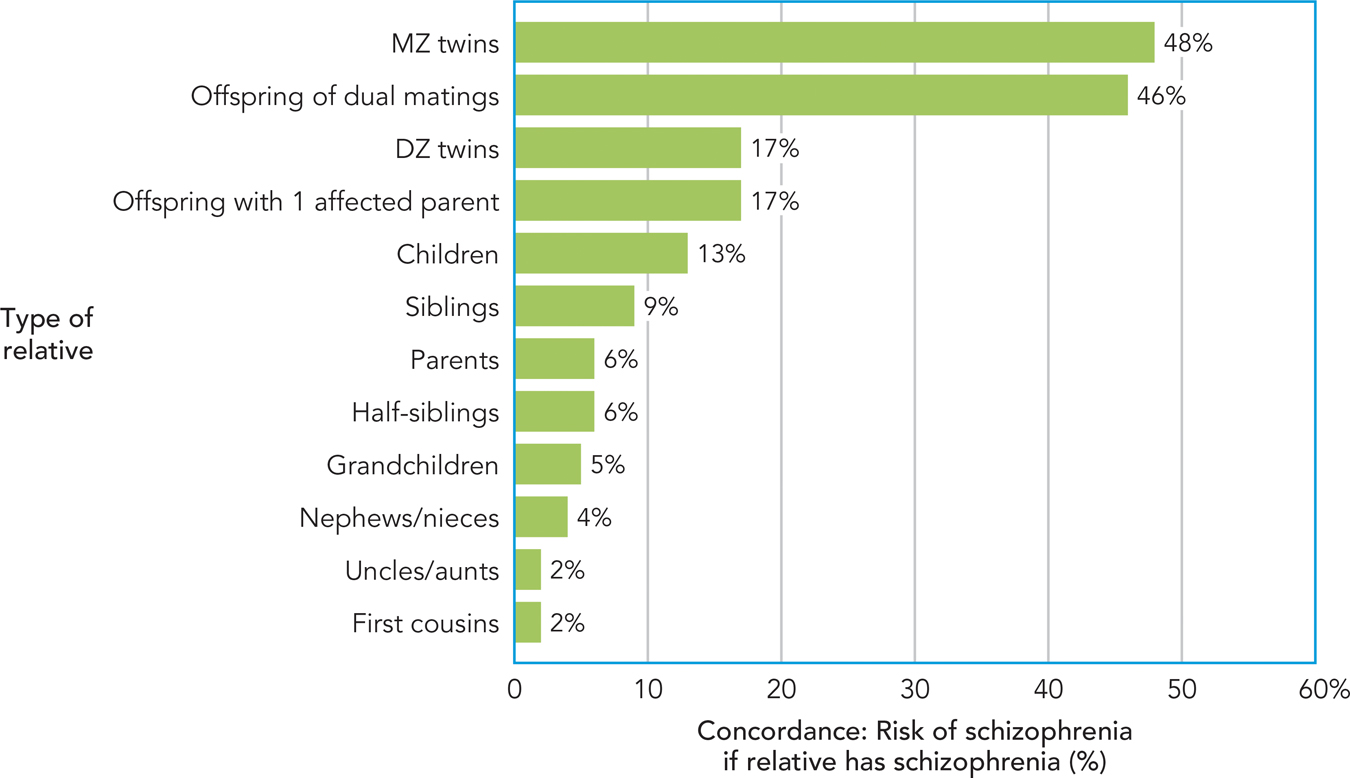

The first question can be answered through twin studies, which compare identical to fraternal twins (see Chapter 4). In a twin study of schizophrenia, researchers determined whether twin pairs differ in concordance, that is, whether the two individuals in a twin pair have the same outcome (i.e., schizophrenia or not). Figure 16.5 shows the results. As you can see, identical, or monozygotic (MZ), twins—

This finding establishes that genetic factors have an effect; specifically, they are a diathesis for schizophrenia (Fowles, 1992). For any medical or psychological disorder, a diathesis is any factor that predisposes a person to experience the disorder.

With that established, one can turn to the second question: Which genes are important, and why? Answering this requires more than twin studies. Researchers must identify (1) specific genes that predict the development of schizophrenia (see Research Toolkit) and (2) the biological processes through which they affect the brain.

Finding genes that make people susceptible to developing schizophrenia is very difficult (Duan, Sanders, & Gejman, 2010). The number of potential genes (more than 1000) is large (Xu et al., 2013). Furthermore, studies require the participation of large numbers of people with schizophrenia—

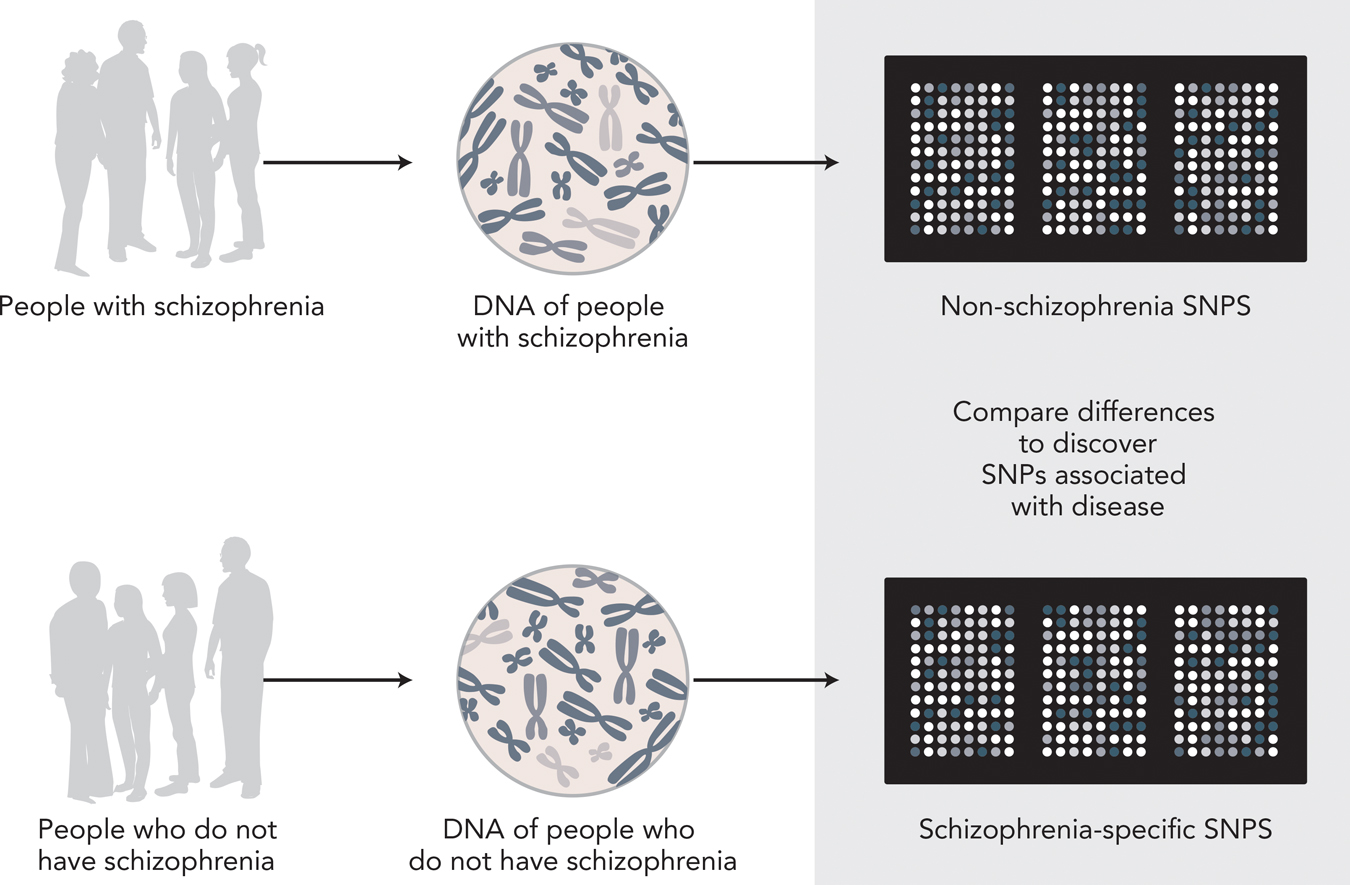

RESEARCH TOOLKIT

Genome-Wide Association Studies

If you want to find a location, a helpful tool is a map. This is true whether the desired location is the nearest entrance to the interstate or a place along the genome where people who have a psychological disorder differ from other people. The genetic map exists; biologists have mapped the human genome—

It sounds complex, but the principle behind the method is simple (Figure 16.6). In a study of genes and schizophrenia, researchers would obtain genetic material (DNA) from people with and without the disorder and then would search for differences in that material.

What the researchers are looking for, specifically, is variations in nucleotides, which are the molecules that make up strands of DNA. The variations are called polymorphisms, which means “more than one form.” Because polymorphisms occur at the level of single, individual nucleotides, researchers look for single-

Have researchers identified the SNPs that contribute strongly to schizophrenia? Not yet. The search has been frustrating. Genome-

The difficulties reflect the sheer numbers involved. In traditional psychological research (see Chapter 2), one or two variables might be studied. But in a genome-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 5

If you were conducting a association study for schizophrenia, you would compare genetic material of people with and without the disease to see how they differed. In particular, you would examine (SNPs) to identify differences in molecules.

Some recent progress has come from a change in strategy. Rather than studying the presence or absence of the disease as a whole, researchers have related genetic material to specific symptoms of schizophrenia. A meta-

Whatever their precise role in schizophrenia, genes alone will never tell the whole story of how this mental illness develops. You can see this for yourself if you look back at Figure 16.6. How similar were identical twins? Their concordance for schizophrenia was not 100% or 99% or 98%. It was only 48%. This means that more than half the time, if one member of an identical twin pair has schizophrenia, the other twin—

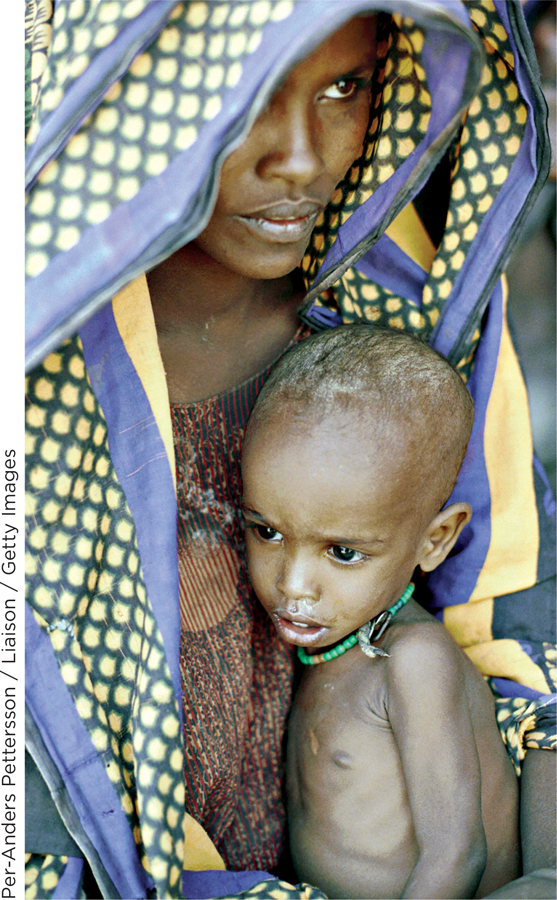

What other factors are important? It’s hard to say; science does not fully understand the causes of schizophrenia. However, some research points to the prenatal environment. A vast amount of brain development occurs before a child’s birth, and prenatal events may interfere with this development in a way that, later in life, results in schizophrenia. Harmful prenatal factors include bodily infections and exposure to lead (Opler & Susser, 2005). Another is poor nutrition. Research conducted in China examined the life outcomes of children conceived in the years 1959 to 1961, a time of catastrophic famine (Xu et al., 2009). These children were twice as likely to develop schizophrenia as were children conceived in other, non-

SCHIZOPHRENIA ACROSS THE LIFE COURSE. It is rare for anyone to develop schizophrenia in early childhood. It is very rare for individuals to develop schizophrenia in their 40s or later in life if they have not had it previously. Among people who have the mental illness, schizophrenia usually first develops between the ages of 16 and 30 (Mueser & McGurk, 2004). Biological changes occurring during puberty may explain why the disease does not develop until the teenage years (Galdos, van Os, & Murray, 1993).

Bad news for sufferers is that schizophrenia persists. The disease generally lasts throughout a person’s lifetime (Mueser & McGurk, 2004), although the severity of positive symptoms of schizophrenia often decreases in older adulthood (Schultz et al., 1997). The vast majority of people who experience an initial episode of schizophrenia will relapse (i.e., will have another such period) subsequently; studies report relapse rates of 95% (Emsley et al., 2013). Treatments for schizophrenia, which we’ll learn about next, help people manage the symptoms, but do not eradicate the disease.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 6

Answer the following questions about schizophrenia.

If schizophrenia was entirely caused by genes, how would the bar for MZ twins in Figure 16.5 change?

Cite at least one factor, other than genes, that may cause schizophrenia.

At what age does schizophrenia develop and how long-

lasting is it? a. If genes alone caused schizophrenia, the bar for MZ twins would be at or near 100%. b. The text cites two other factors: prenatal events, including bodily infections or exposure to lead, and poor nutrition. c. Schizophrenia develops between ages 16 and 30 and persists throughout one’s lifetime.

Therapy for Schizophrenia

Preview Questions

Question

What drugs are used to treat schizophrenia? What are the side effects? Do they work?

What drugs are used to treat schizophrenia? What are the side effects? Do they work?

What psychotherapies are used to treat schizophrenia?

What psychotherapies are used to treat schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia exerts a huge cost on individuals and society at large. Treating the disorder is thus one of the greatest challenges for psychological science. Let’s see how it’s done.

DRUG THERAPY. You’ve learned enough about schizophrenia that, when it comes to the question of how to treat it, you can take an educated guess. Excess dopamine-

To treat schizophrenia, psychiatrists prescribe antipsychotic drugs, which are medications that alter the action of neurotransmitters in the brain in a manner that reduces psychotic symptoms. The drugs generally target the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Two types of antipsychotic drugs are available: typical and atypical antipsychotics. Their names indicate the historical time of their development. Typical antipsychotics are those developed first, in the 1950s. Atypical antipsychotics were developed in the 1990s, by which time use of the previously developed drugs was “typical.” One commonly used typical antipsychotic is chlorpromazine (which has the trade name thorazine). A common atypical antipsychotic is the drug clozapine.

Both typical and atypical antipsychotics lower dopamine-

Although typical and atypical antipsychotics both affect dopamine in this manner, in other ways they differ. Atypical antipsychotics affect not only dopamine signaling, but also signaling by a second neurotransmitter, serotonin. Serotonin contributes to emotional feelings that occur when people pursue activities that they find rewarding (Kranz, Kasper, & Lanzenberger, 2010). By influencing serotonin, atypical antipsychotic drugs thus may benefit not just positive symptoms of schizophrenia, but negative symptoms such as flat affect and lack of motivation, too (Stahl, 2002). A second difference is that the typical antipsychotics have a side effect that is not usually produced by the atypical drugs (Geddes et al., 2000), namely, uncontrollable, “shaking” muscular movements.

Unfortunately for patients with schizophrenia, both types of antipsychotic medication can produce a side effect known as tardive dyskinesia. Tardive dyskinesia consists of repetitive, involuntary movements of facial muscles. These movements result in odd symptoms such as repeated grimacing and lip smacking. For some patients, tardive dyskinesia is irreversible; it continues even after they stop taking the antipsychotic medication that triggered it (Muench & Hamer, 2010). Tardive dyskinesia rates are lower with atypical than typical antipsychotics (Kane, 2004).

EFFECTIVENESS OF ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS. The good news is that antipsychotic drugs work for many patients, substantially reducing their positive symptoms of schizophrenia. As a result, people who otherwise might be hospitalized can live in their regular community. One study finds that, among patients treated for schizophrenia, 40% experience significant periods of recovery, that is, periods during which they are free from schizophrenic symptoms and can hold a job and take part in social activities (Harrow et al., 2005). The scholar you read about in this chapter’s opening, Dr. Elyn Saks, is an example. She lives with schizophrenia yet leads an exceptionally productive professional life, in part thanks to antipsychotic drugs (Saks, 2007).

There are, however, two pieces of bad news. First, antipsychotic drugs do not always work. Reviews indicate that at least half the patients taking the drugs do not experience substantial long-

PSYCHOTHERAPY. Drugs can reduce the delusions and hallucinations of schizophrenia, but these symptoms are only part of the story. Schizophrenia affects the person as a whole. People with schizophrenia question themselves—

A key question about psychotherapies for schizophrenia is which ones work. Which therapies, in other words, are empirically supported? (Also see Chapter 15.) One approach with empirical support is cognitive therapy. Cognitive therapists engage in a dialogue with patients about their delusional beliefs (Beck & Rector, 2002). They encourage patients to question the accuracy of the beliefs—

Some therapists employ cognitive strategies while also emphasizing the usefulness of humanistic approaches. The humanistic approach to therapy for schizophrenia focuses on the person as a whole: the individual who must cope not only with symptoms of schizophrenia, but also with the changes in lifestyle and self-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 7

Which of the following statements about treatments for schizophrenia are true?

Both typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs reduce dopamine signals by blocking receptor sites.

A. B. Both typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs alleviate positive symptoms, and atypical psychotics can additionally alleviate negative symptoms, by affecting serotonin signaling.

A. B. Most people with schizophrenia who take antipsychotics experience significant periods of recovery, enabling them to live relatively normal lives.

A. B. Side effects of antipsychotics include tardive dyskinesia, sluggishness, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction.

A. B. The side effects of antipsychotics are mild enough that few people stop taking the drugs.

A. B. Cognitive therapists help people with schizophrenia to challenge their delusional beliefs and to cope with the stress those beliefs create.

A. B. Humanistic therapists help people with schizophrenia cope with changes in their self-

concept. A. B.

Other Psychotic Disorders

Preview Question

Question

Is schizophrenia the only psychotic disorder?

Is schizophrenia the only psychotic disorder?

We have examined schizophrenia in depth for two reasons. One, as noted earlier, is that its personal cost to individuals and its economic cost to society—

Schizophrenia, however, is not the only psychotic disorder. There are other psychological disorders in which people experience psychotic symptoms, but not with the severity and duration seen in schizophrenia. Two of them are brief psychotic disorder and delusional disorder.

In brief psychotic disorder, people experience the same types of symptoms as in schizophrenia (delusions, hallucinations, etc.). However, they experience them—

In delusional disorder, people experience only one psychotic symptom, delusions, which may persist indefinitely. People with the disorder may believe, without evidence, that they are being spied upon, that someone is trying to poison them, or that they have made some profoundly important discovery that society has not recognized. Some beliefs held by people with delusional disorder may be wildly implausible (DSM-

Brief psychotic disorder and delusional disorder illustrate that psychoses exist on a continuum. There is, in other words, a dimension—

These survey findings can help reduce the social stigma associated with psychotic disorders. Social stigma refers to widespread negative beliefs about a group. Societies around the world stigmatize people with psychotic disorders (Lee, 2002). The stigma portrays them as “lunatic, “crazy” individuals who differ fundamentally from “normal” members of society. In surveys of people with schizophrenia, 4 in 5 individuals report overhearing hurtful, offensive comments about mental illness from other people or the media, and the majority indicate that people sometimes try to avoid them (Wahl, 1999). These experiences can create stress, lower self-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

The following statement is incorrect. Explain why: “Two pieces of information suggest that psychotic disorders are best conceptualized as distinct categories, rather than dimensions: (1) 10% of people have experienced delusions such as hallucinations, and (2) brief psychotic disorder and delusional disorder share symptoms with schizophrenia, but in lesser form.”