Effectiveness of Macroeconomic Policy: Phillips Curves and Rational Expectations

The persistent unemployment that occurred after the 2007–2009 recession in what is known as a jobless recovery had economists debating the right policy to use. Fiscal policy was undertaken to boost market activity, at the cost of rising debt. And significant monetary policy actions were taken to inject the economy with more money, at the cost of potential inflation. Questions that arise from these policies include whether the effort to reduce unemployment could result in higher inflation, or whether macroeconomic policy has any short-term effects at all. We address these issues in this section by studying two theories developed in the 1950s and 1960s: the Phillips curve and rational expectations.

With Phillips curve analysis, it first seemed that fiscal policy was easy: Pick an unemployment rate from column A and get a corresponding inflation rate from column B. Unfortunately, reality turned out to be much more complex. With rational expectations, the question was whether policy could ever be effective at all.

Unemployment and Inflation: Phillips Curves

Phillips curve The original curve posited a negative relationship between wages and unemployment, but later versions related unemployment to inflation rates.

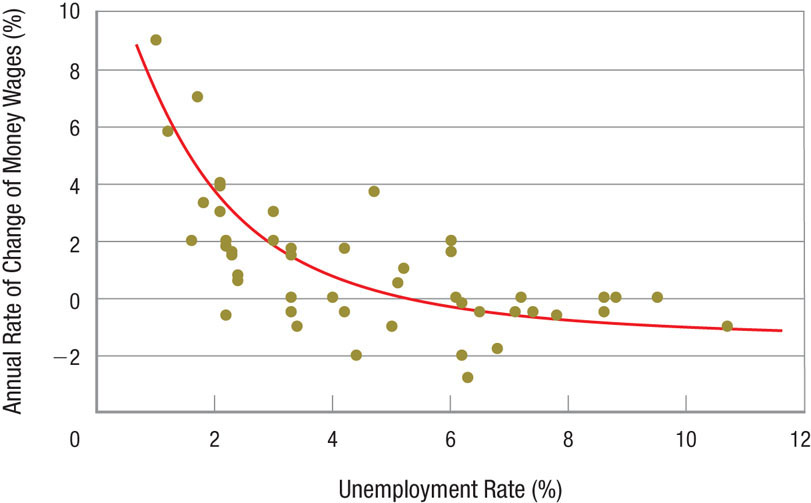

Does a relationship exist between unemployment and inflation? In his early work, A. W. Phillips compared the rate of change in money wages to unemployment rates in Britain over the years 1861 to 1957. The negatively sloped curve shown in Figure 2 reflects his estimate of how these variables were related and has been called a Phillips curve in his honor. As you can see, when unemployment rises, wage rates fall.

FIGURE 2

The Original Phillips Curve for Britain (1861–1957) A. W. Phillips compared the rate of change in money wages to unemployment rates in Britain from 1861 to 1957. The resulting nonlinear, negatively sloped curve is the first example of a Phillips curve. When unemployment rises, wage rates fall, and vice versa. Note that some dots represent multiple years.

What explains this negative relationship between wages and unemployment? Labor costs or wages are typically a firm’s largest cost component. As the demand for labor rises, labor markets will tighten, making it difficult for employers to fill vacant positions. Hence, wages rise as firms bid up the price of labor to attract more workers. The opposite happens when labor demand falls: Unemployment rises and wages decline.

This relationship can be seen in specific industries that have seen spikes or downturns in employment. For example, demand for health care professionals increased in the past decade, reducing unemployment in the industry. Those who pursue a career in nursing, medicine, or other health-related fields saw their salaries increase relative to those in other careers. On the other hand, the collapse of the financial and housing sectors forced many realtors, loan specialists, and construction workers out of work. Those lucky enough to find work often made less than they did during the housing boom.

The market relationship between wages and unemployment will clearly affect prices. But worker productivity also plays an important role in determining prices.

Productivity, Prices, and Wages We might think that whenever wages rise, prices must also rise. Higher wages mean higher labor costs for employers—costs that businesses then pass along as higher prices. But this is not always the case. If worker productivity increases enough to offset the wage increase, then product prices can remain stable. The basic relationship among wages, prices, and productivity is

Inflation = Increase in Nominal Wages − Rate of Increase in Labor Productivity

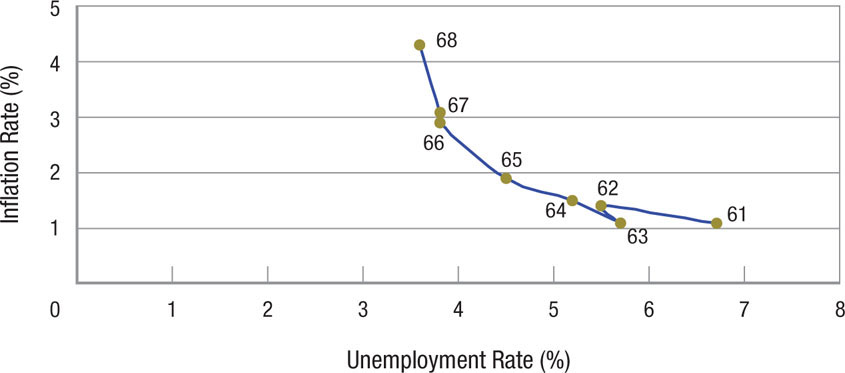

For example, when wages increase by 5% and productivity increases by 3%, inflation is 2%. Given this relationship, the Phillips curve can be adapted to relate productivity to inflation and unemployment, as shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

The Phillips Curve A rise in wages may cause a rise in prices, but if worker productivity increases sufficiently to offset the wage increase, product prices can remain stable. When the rates of change in productivity and wages are equal, inflation is zero (point a). This is the natural rate of unemployment. If policymakers want to use expansionary policy to reduce unemployment from un to u1, they must be willing to accept inflation of p1. Reducing unemployment further to u2 would raise inflation to p2 as labor markets tighten and wages rise more rapidly than productivity.

Notice that when the rates of change in productivity and wages are equal, inflation is zero (point a). This occurs at the natural rate of unemployment, the unemployment rate when inflationary pressures are nonexistent. Therefore, higher rates of productivity growth mean that for a given level of unemployment, inflation will be less (the Phillips curve would shift in toward the origin).

If policymakers want to use expansionary policy to reduce unemployment from un to u1, then according to the curve shown in Figure 3, they must be willing to accept inflation of p1. To reduce unemployment further to u2 would raise inflation to p2 as labor markets tightened and wages rose more rapidly.

Figure 4 shows the Phillips curve for the United States during the 1960s. Notice the nearly smooth negative relationship between the two variables, much like that in the last two figures. As unemployment fell, inflation rose. This empirical relationship led policymakers to believe that the economy presents them with a menu of choices. By accepting a minor rise in inflation, they could keep unemployment low. Alternatively, by accepting a rise in unemployment, they could keep inflation near zero.

FIGURE 4

The Phillips Curve—1960s The Phillips curve for the United States during the 1960s gives a smooth negative relationship between inflation and unemployment, much like that found in the last two figures. Using this relationship, policymakers concluded that an inflation rate of 3% to 4% was required to keep unemployment below 4%.

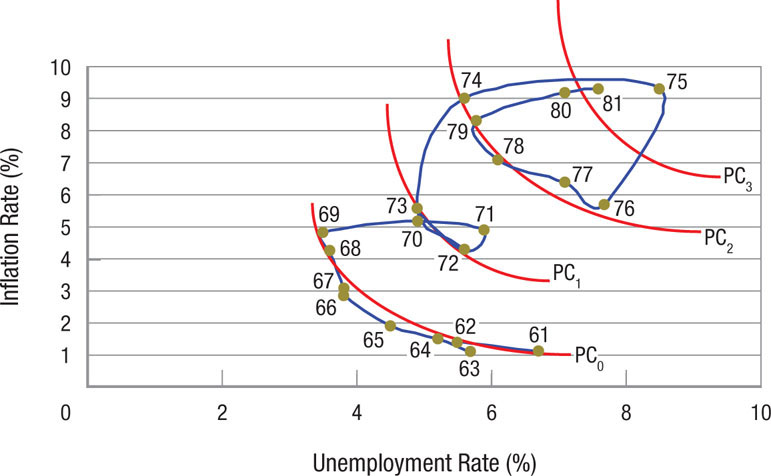

But just as policymakers were getting used to the ease of making policy by accepting moderate inflation in exchange for lower unemployment rates, the economy played a big trick on them. As Figure 5 shows, the entire Phillips curve began shifting outward during the early 1970s.

FIGURE 5

The Phillips Curve from 1961–1981: Instability and Supply Shocks Just as policymakers were getting used to accepting moderate inflation in exchange for lower unemployment rates, the economy surprised them. The entire Phillips curve began shifting outward during the early 1970s. Unemployment rates that, in the 1960s, had been associated with modest inflation of 2% to 3% quickly began requiring twice that rate. The inflation-unemployment tradeoff worsened throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s, largely due to oil price shocks and rising inflationary expectations. Inflation and unemployment continued to rise, creating stagflation. By 1980, annual inflation was over 9%, and unemployment was over 7%.

What looked to be an easy tradeoff between inflation and unemployment turned ugly. Unemployment rates that, in the 1960s, had been associated with modest inflation of 2% to 3% quickly began requiring twice that rate in the early 1970s. By the late 1970s, these same unemployment rates were generating annual inflation rates approaching double digits. The reason for these shifts turned out to be the oil supply shocks of the mid-1970s and the rising inflationary expectations that followed.

The Importance of Inflationary Expectations Workers do not work for the sake of earning a specific dollar amount, or a specific nominal wage. Rather, they work for the sake of earning what those wages will buy—for real wages. Consequently, when they bargain for wage increases, workers will take their past experiences with inflation into account.

inflationary expectations The rate of inflation expected by workers for any given period. Workers do not work for a specific nominal wage but for what those wages will buy (real wages), therefore their inflationary expectations are an important determinant of what nominal wage they are willing to work for.

Taking inflationary expectations into account, wage increases can be connected to unemployment and expected inflation by adding a variable, pe, representing inflationary expectations, to the inflation equation introduced earlier:

Inflation = Increase in Nominal − Wages Rate of Increase in Labor Productivity + Pe

In other words, the same tradeoff between inflation and unemployment in the short-run Phillips curve existed as we saw before, but there is a unique tradeoff for each level of inflationary expectations.

For example, suppose there are no inflationary expectations, and productivity is growing at a 3% rate when the economy’s unemployment rate is 4%. In this scenario, if nominal wages increase by 5%, inflation would be 5% − 3% + 0% = 2%. However, if inflationary expectations (pe) grow to, say, 4%, the Phillips curve will shift outward in Figure 5, and the inflation rate now associated with 4% unemployment will be 5% − 3% + 4% = 6%.

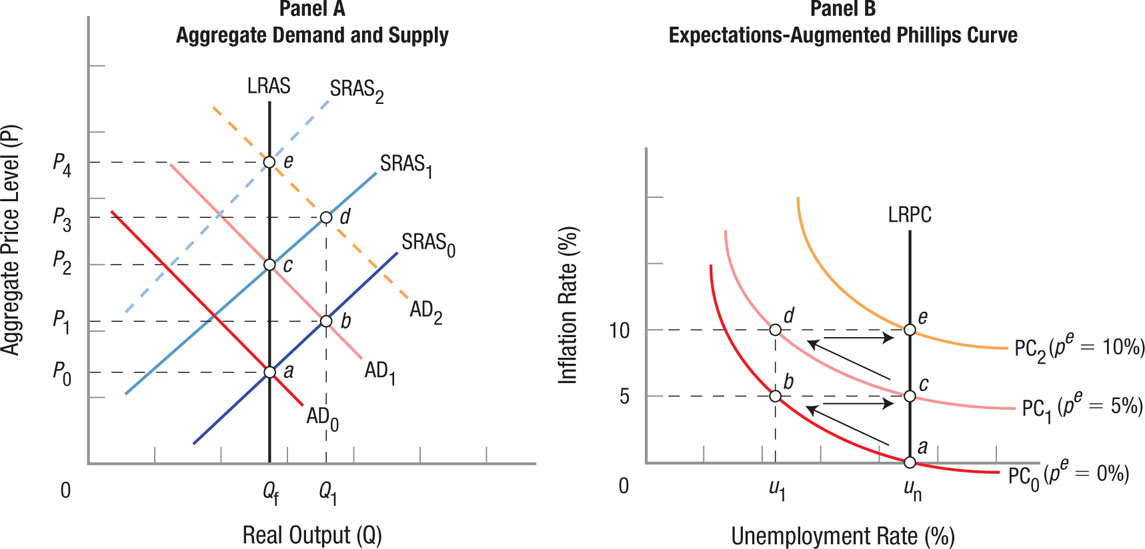

Inflationary Expectations and the Phillips Curve Panel B of Figure 6 shows a Phillips curve augmented by inflationary expectations. The economy begins in equilibrium at full employment with zero inflation (point a in panel B). Panel A shows the aggregate demand and supply curves for this economy in equilibrium at point a. Note that the economy is producing at full employment output of Qf, and this translates to the natural rate of unemployment, un, in panel B.

FIGURE 6

Aggregate Demand, Aggregate Supply, and the Expectations-Augmented Phillips Curve Panel A shows the economy’s aggregate demand and supply curves, and panel B shows the economy’s Phillips curve, augmented by inflationary expectations. Using expansionary policies to reduce unemployment below un, policymakers shift aggregate demand in panel A from AD0 to AD1. This moves the economy to point b, with real output and the price level rising to Q1 and P1. Unemployment declines to u1 (point b in panel B), but inflation rises to something approaching 5%. If policymakers attempt to hold unemployment below the natural rate, the economy will endure accelerating inflation. The long-run Phillips curve (LRPC) in panel B shows the relationship between inflation and unemployment when the inflation rate is just equal to inflationary expectations.

The Phillips curve in panel B is initially PC0 (pe = 0%). Thus, inflation is equal to zero and so are inflationary expectations (pe).

Now assume, however, that policymakers are unhappy with the economy’s performance and want to reduce unemployment below un. Using expansionary policies, they shift aggregate demand in panel A from AD0 to AD1. This moves the economy to point b; real output and the price level rise, to Q1 and P1.

In panel B, meanwhile, the unemployment rate has declined to u1 (point b), but inflation has risen to 5%. Workers had anticipated zero inflation; this unanticipated inflation means that real wages have fallen. Therefore, workers will begin asking for raises, and employers wanting to keep turnover at a minimum may well begin offering higher wages.

The Long-Run Phillips Curve The long-run Phillips curve (LRPC), shown in panel B of Figure 6 as the vertical line at full employment (unemployment = un), shows the long-term relationship between inflation and unemployment when the inflation rate and the expected inflation rate are equal. The LRPC is the Phillips curve counterpart to the vertical long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) in panel A.

Accelerating Inflation As nominal wages rise, the result in panel A is that, over time, the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts leftward to SRAS1, thus moving the economy back to full employment at point c. In panel B, with inflation now running at 5%, the Phillips curve shifts outward to PC1 (pe = 5%). Workers, however, now expect 5% inflation, and the economy moves back to point c. Unemployment has moved back to its natural rate, but inflationary expectations have risen to 5%. The aggregate price level, meanwhile, has risen from P0 to P2, or 5%.

At this point, in order for policymakers to move the economy back to u1 (or Q1), they must repeat the process of expanding aggregate demand, only this time, the economy is starting from a higher Phillips curve because inflationary expectations are already elevated.

The implications of this analysis for fiscal and monetary policymakers who want to fine-tune the economy and keep unemployment below the natural rate are not pleasant. If policymakers want to keep unemployment below the natural rate, they must continually increase aggregate demand so that inflation will always exceed what is expected. Thus, policymakers must be willing to incur a permanently accelerating rate of inflation—hardly a popular idea.

stagflation Simultaneous occurrence of rising inflation and rising unemployment.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, oil price shocks and rising inflationary expectations caused both inflation and unemployment to rise, creating what economists call stagflation. Where under the original Phillips curve the conclusion was that rising unemployment would be met by falling inflation, the 1970s witnessed rising unemployment and rising inflation as the Phillips curve shifted outward. By 1980, inflation was over 9% and unemployment was over 7%.

Returning Inflation to Normal Levels To eliminate inflationary pressures when they arise, policymakers must be willing to curtail growth in aggregate demand and accept the resulting higher rates of unemployment for a certain transition period. How long it takes to reduce inflation and return to the natural rate of unemployment will depend on how rapidly the economy adjusts its inflationary expectations. Policymakers can speed this process along by ensuring their policies are credible, for instance, by issuing public announcements that are consistent with contractionary policies in both the monetary and fiscal realms.

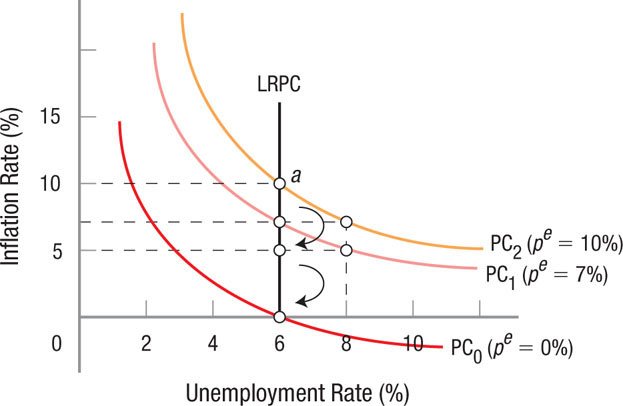

Figure 7 below illustrates how inflationary expectations are reduced to bring about a more favorable tradeoff. Initially, the economy is in equilibrium at point a, with the economy at the natural rate of unemployment of 6% and inflation at 10%.

FIGURE 7

Phillips Curves and Disinflation In the disinflation process, the economy initially is in equilibrium at point a. To reduce inflationary expectations, policymakers must reduce aggregate demand and push the economy into a recession, increasing unemployment to 8%. As aggregate demand slumps, wage and price pressures soften, reducing inflationary expectations. As these expectations decline, the entire Phillips curve shifts inward, from PC2 to PC1. If the process goes on long enough, the Phillips curve will shift back to PC0. The arrows here show the path the economy must take back to roughly stable prices at the natural unemployment rate.

To reduce inflationary expectations, policymakers must be willing to reduce aggregate demand and push the economy into a recession, increasing unemployment to 8%. As aggregate demand slumps, wage and price pressures will soften, reducing inflationary expectations. As these expectations decline, the Phillips curve shifts inward, from PC2 to PC1, and if the process goes on long enough, the Phillips curve will eventually shift back to PC0. The arrows in Figure 7 show the path the economy must take to lower inflation rates. How fast this occurs depends on the severity of the recession and the confidence the public has that policymakers are willing to stay the course.

The Bernanke Inflation Jump—When?

After the federal funds target rate was lowered to an effective rate of 0% in December of 2008, the Federal Reserve embarked on a series of alternative bond buying activities (such as the purchase of risky mortgage-backed securities) in order to continue its use of expansionary monetary policy to speed the economic recovery. These quantitative easing policies became known by their sequence, from QE1 to QE4.

During this time, the Fed altered its balance sheet from one containing mostly safe U.S. Treasury bonds to one that at one point consisted of over $1 trillion worth of risky mortgage-backed securities. These efforts at easing credit markets through bond purchases cannot be sustained long-term, because inflation would result. In fact, the vast amount of bond purchases has already set the stage for a rise in inflation as consumer and business confidence continues to rise. There’s simply too much money chasing a limited amount of output.

Economists predict that as the economy recovers, the Fed will eventually halt its QE programs, causing interest rates to rise. But before it does, the Fed continues to walk a fine line between easing credit markets and keeping inflation in check. When the Fed announced QE3 and QE4 in 2012, it did not provide a specific end date; instead, it committed to keeping interest rates low until the unemployment rate falls toward the natural rate.

However, this uncertainty added to the nervousness that businesses and investors experienced as different people held different expectations about the Fed’s actions. In fact, markets in 2013 battled between optimism as the economy continued to recover and fear that it would come to a screeching halt once the Fed inevitably ends its expansionary monetary policies to prevent a rise in inflation. Alternatively, the Fed could have announced the end date right away.

Two questions remain. First, did the Fed’s failure to set an end date produce enough uncertainty that it harmed the economy more than its policies helped? After all, when consumers and businesses face too much uncertainty, they hold off on spending and investing until the uncertainty clears up. Second, does the economy have enough momentum to sustain economic growth without expansionary monetary policy? Time will tell.

In 1981, the Reagan administration launched a long-term program designed to increase economic growth and reduce inflation. The Reagan administration took the view that stagflation had arisen from a substantial increase in the government’s role in the economy, and responded with policies that reduced government spending, taxes, and regulations. This aggressive plan of wringing stagflation out of the U.S. economy took the better part of the 1980s. Inflation that took over a decade to develop required nearly another decade to be resolved. Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, who insisted on keeping interest rates high in the face of fierce public opposition, deserves much of the credit for this triumph over inflation.

This lesson about the importance of restraining monetary growth and focusing on stable prices was not lost on the next Fed chairman, Alan Greenspan. Throughout the 1990s, the Fed maintained a tight watch on inflation, which fell from around 4% to near 1%.

The importance of keeping inflation low has continued to influence policymaking today. As long as the threat of inflation remains low, policymakers have been willing to use expansionary policy to promote economic growth and reduce unemployment, exactly what the Phillips curve suggests would be effective. These policies assume that inflation expectations adjust with a noticeable lag, allowing some tradeoff between inflation and unemployment to exist. Some economists, however, argue that consumers and businesses adapt their expectations so rapidly that their behavior tends to nullify much of policymakers’ actions, which we will discuss next.

adaptive expectations Inflationary expectations are formed from a simple extrapolation from past events.

Rational Expectations and Policy Formation The use of expectations in economic analysis is nothing new. Keynes believed that expectations are driven by emotions. He suggested that investors in the stock market will jump on board trends without attempting to understand the underlying market dynamics. Milton Friedman developed his model of expectations using what are known as adaptive expectations, whereby people are assumed to perform a simple extrapolation from past events. Workers, for example, are assumed to expect that past rates of inflation, averaged over some time period, will continue into the future. Adaptive expectations are represented by a backward-looking model of expectations, which contrasts with the rational expectations model.

rational expectations Rational economic agents are assumed to make the best possible use of all publicly available information, then make informed, rational judgments on what the future holds. Any errors in their forecasts will be randomly distributed.

In the rational expectations model developed by Robert Lucas, rational economic agents are assumed to make the best possible use of all publicly available information about what the future holds before making decisions. This does not mean that every individual’s predictions about the future will be correct. Those errors that do occur will be randomly distributed, such that the expectations of large numbers of people will average out to be correct.

Assume that the economy has been in an equilibrium state for several years with low inflation (2%) and unemployment (6%). In such a stable environment, the average person would expect the inflation rate to stay right about where it is indefinitely. But now assume that the Fed announces it is going to increase the rate of growth of the money supply significantly. Basic economic theory tells us that this action will translate into higher prices, bringing about higher future inflation rates. Knowing this, households and businesses will revise their inflationary expectations upward.

NOBEL PRIZE ROBERT LUCAS

In the 1970s, a series of articles by Robert E. Lucas changed the course of contemporary macroeconomic theory and profoundly influenced the economic policies of governments throughout the world. His development of the rational expectations theory challenged decades of assumptions about how individuals respond to changes in fiscal and monetary policies.

Lucas was born in 1937 in Yakima, Washington. His father was a welder, who advanced through the ranks to become president of a refrigeration company. Lucas was awarded a scholarship to the University of Chicago. He had wanted to be an engineer, but the University of Chicago did not have an engineering school, so he studied history instead. After briefly attending the University of California, Berkeley, where he developed an interest in economics, he returned to the University of Chicago, earning his Ph.D. in 1964. One of his professors was Milton Friedman, whose skepticism about interventionist government policies influenced a generation of economists. Lucas began his teaching career at Carnegie-Mellon University and later became a professor at the University of Chicago.

Before Lucas, economists accepted the Keynesian idea that expansionary policies could lower the unemployment rate. Lucas, however, argued that the rational expectations of individual workers and employers would adjust to the changing inflationary conditions, and unemployment rates would rise again. Lucas developed mathematical models to show that temporarily cutting taxes to increase spending was not a sound policy because individuals would base their decisions on expectations about the future, and these temporary tax cuts would find their way into savings and not added spending. In other words, individuals were rational, forward thinking, and perfectly able to adapt to changing economic information.

When the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Lucas the Nobel Prize in 1995, it credited Lucas with “the greatest influence on macroeconomic research since 1970.”

As this example shows, people do not rely only on past experiences to formulate their expectations of the future, but instead use all information available to them, including current policy announcements and other information that gives them reason to believe the future might hold certain changes. If adaptive expectations are backward looking, rational expectations are forward looking.

Policy Implications of Rational Expectations Do individuals and firms really form their future expectations as the rational expectations hypothesis suggests? If so, the implications for macroeconomic policy would be enormous; indeed, it could leave macroeconomic policy ineffective.

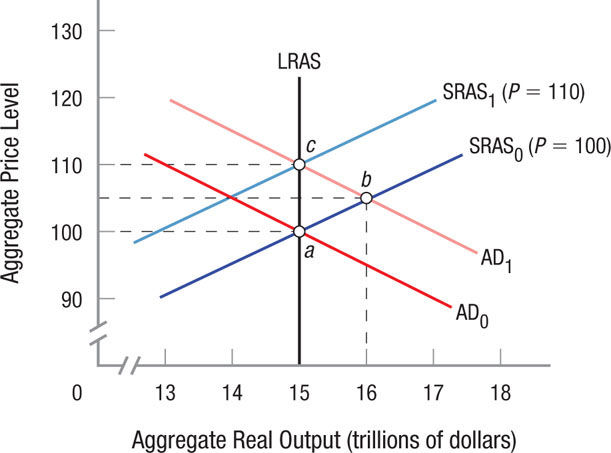

To illustrate, let us assume that the economy depicted in Figure 8 is operating at full employment at point a. Short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS0 (P = 100) reflects current inflationary expectations. Suppose the Fed announces that it intends to increase the money supply.

FIGURE 8

Rational Expectations: The Policy Ineffectiveness Hypothesis Rational expectations theory suggests that macroeconomic policy will be ineffective, even in the short term. Assume that the economy is operating at full employment (point a) and short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS0 (P = 100). Now suppose that the Fed announces that it intends to increase the money supply. Expanding the money supply will shift aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1, and this will increase the demand for labor and raise nominal wages. Yet, as soon as the Fed announces it is going to increase the money supply, rational economic agents will use this information immediately to raise their inflationary expectations. Thus, output will remain unchanged, though the price level rises immediately to 110.

Expanding the money supply will shift aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1. This will increase the demand for labor and raise nominal wages. But what happens next?

Natural rate theorists, using adaptive expectations, would argue that workers will be fooled into thinking that the increase in money wages represents a real raise, thus driving output and employment up to $16 trillion (point b). After a time, however, workers will realize that real wages have not risen because prices have risen by at least as much as wages. Aggregate supply will then fall to SRAS1 (P = 110) as price expectations climb and the economy gradually moves back to full employment at a higher price level (point c). In this scenario, the Fed’s policy succeeds in raising output and employment in the short term, but at the expense of a long-term rise in the cost of living.

Contrast this with the rational expectations model. When the Fed announces that it is going to increase the money supply, perfectly rational individuals and firms will listen to this information and immediately raise their inflationary expectations. In Figure 8, output will remain unchanged because the price level will rise immediately to 110. No one gets fooled into temporarily increasing output or employment, even though the increase in the money supply still drives up prices. Therefore, any announcement of a policy change will result in an immediate move to a new long-run equilibrium, leaving the short-term aspects of the policy change ineffective.

This suggests that if the Fed wants to use an increase in the money supply to raise output and employment in the short term, the only way it can do so is by not announcing its plans; it must essentially force individuals and firms to make decisions with substantially incomplete information.

A Critique of Rational Expectations To date, empirical assessments of the ineffectiveness of macroeconomic policy based on rational expectations have yielded mixed results. In general, these studies do not support the policy ineffectiveness proposition. That is, macroeconomic policies do have a real impact on the economy, and monetary policies are credited with keeping inflation low over the past three decades.

New Keynesian economists have taken a different approach to critiquing rational expectations theory. Both the adaptive and the rational expectations models assume that labor and product markets are highly competitive, with wages and prices adjusting quickly to expansionary or contractionary policies. The new Keynesians point out, however, that labor markets are often beset with imperfect information, and that efficiency wages often bring about short-term wage stickiness.

efficiency wage theory Employers often pay their workers wages above the market-clearing level to improve morale and productivity, reduce turnover, and create a disincentive for employees to shirk their duties.

Imperfect information occurs when firms and workers do not have up-to-the-minute information on economic fluctuations due to timing lags, causing wages and prices to not react quickly. Efficiency wage theory disputes the notion that labor markets are like competitive commodity markets with equal prices. For all labor is not equal. People need incentives to work hard, and paying workers an efficiency wage, or a wage above the market-clearing level, is one form of motivation to improve morale and productivity.

Imperfect information and efficiency wages suggest that wages and prices may be sticky because workers and firms are either unable or unwilling to make adjustments quickly to changes in the economy. This means that neither workers nor firms can react quickly to changes in monetary or fiscal policy. And this would give such policies a chance of a short-term impact.

Although the policy ineffectiveness proposition has not found significant empirical support, rational expectations as a concept has profoundly affected how economists approach macroeconomic problems. Nearly all economists agree that policy changes affect expectations, and that this affects the behavior of individuals and firms that potentially reduce the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy.

This section has considered two challenges to the effectiveness of macroeconomic policy. First, we looked at the Phillips curve, and showed that policies attempting to address unemployment could lead to inflation and a build-up in inflationary expectations. In other words, policymakers do not face an easy choice between rates of unemployment and rates of inflation. Second, we looked at rational expectations and showed how expectations could mitigate the effectiveness of policy.

In the next section, we now want to apply these concepts to macroeconomic issues that are important in our future: jobless recoveries, debt and long-run inflation, and the role of globalization in influencing economic growth.

EFFECTIVENESS OF MACROECONOMIC POLICY: PHILLIPS CURVES AND RATIONAL EXPECTATIONS

- The Phillips curve represents the negative relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. When the unemployment rate goes up, inflation goes down, and vice versa.

- Phillips curves are affected by inflationary expectations. Rising inflationary expectations by the public would be reflected in a shift in the Phillips curve to the right, worsening the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.

- If policymakers use monetary and fiscal policy to attempt to keep unemployment continually below the natural rate, they will face accelerating inflation. Reducing inflation requires that policymakers curtail aggregate demand and accept higher rates of unemployment during the transition period back to low inflation.

- Adaptive expectations assume that individuals and firms extrapolate from past events; it is a backward-looking model. Rational expectations assume that individuals and firms make the best possible use of all publicly available information; it is a forward-looking model of expectations.

- Rational expectations analysis leads to the conclusion that policy changes will be ineffective in the short run because individuals will immediately adjust to the long-run consequences of the policy.

- Market imperfections and information problems are two reasons why the policy ineffectiveness conclusions of rational expectations analysis have met with mixed results empirically.

QUESTIONS: If an economy has high unemployment but low inflation, what would the Phillips curve suggest to be an appropriate macroeconomic policy? Would your answer change if inflationary expectations rise? If we assume that all individuals and firms have excellent foreknowledge as described by the rational expectations model, would that change your answer?

The Phillips curve would suggest that unemployment can be reduced by accepting a higher rate of inflation. As long as inflation is very low, a small rise in inflation would be a small cost to pay for pushing the unemployment rate down. However, if inflationary expectations rise, it would require a greater inflation rate to achieve a lower unemployment rate. Here, policymakers must be careful not to let inflation exceed a level that might cause larger problems for the economy. Finally, if individuals and firms acted according to the rational expectations model, any increase in inflation would never lead to a reduction in unemployment. In this case, macroeconomic policy is ineffective in the short run, and the best prescription would be to leave the market alone to correct itself over time.