THE DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME AND WEALTH

income A flow measure reflecting the funds received by individuals or households over a period of time, usually a week, month, or year.

wealth A stock measure of an individual’s or family’s assets, net of liabilities, at a given point in time.

Income is a flow, wealth is a stock. Income measures the receipt of funds by individuals or households over time, usually a week, month, or year. Income is a flow of funds measure. Wealth, in contrast, measures a family’s assets net of liabilities, at a given point in time. You may earn a certain income in 2017, but your net wealth is measured on a specific day, say, December 31, 2017. Many people were wealthy on January 1, 2007, but after suffering the ravages of a falling housing and stock market, they were considerably less wealthy on July 1, 2009.

You can be wealthy with low income if you do not work and your assets are in homes, stocks, and bonds that earn little to no interest or dividends. Alternatively, you can have little wealth, yet a high income, if you are like a rookie professional ballplayer who earns a seven-

Life Cycle Effects

Family and individual incomes vary significantly over the course of people’s lives. Young people just starting their careers often earn only a modest income. Over their working careers, they become more experienced and their salaries increase, with income peaking roughly between the ages of 45 and 55. At some point between ages 45 and 60, family size begins to decline as the kids grow up and leave home. As people approach 60, income begins declining, while household saving rises as they prepare for retirement. Incomes decline with retirement, but then again, so do family responsibilities.

One result of this economic life cycle is that an aging society can expect to see changes in income distribution as a greater number of households falls into lower income brackets. The life cycle also has implications for the economic effects of immigration. Newcomers to the United States often possess limited skills; therefore, when the country admits more immigrants, it can expect more low-

The Distribution of Income

functional distribution of income The distribution of income for resources or factors of production (land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurial ability).

Income distribution can be considered from several different perspectives. First, we can look at the functional distribution of income, which splits income among the inputs (factors) of production. The functional distribution for the United States between 1929 and 2015 is shown in Table 1.

| TABLE 1 | FUNCTIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME (ABSOLUTE DOLLARS IN BILLIONS, NUMBERS IN PARENTHESES ARE PERCENTAGES OF TOTAL INCOME) | ||||

| Year | Wages | Proprietor’s Income | Rent | Corporate Profits | Net Interest |

| 1929 | 51.1 (60.3) | 14.9 (17.6) | 4.9 (5.8) | 9.2 (10.8) | 4.7 (5.5) |

| 1940 | 52.1 (65.4) | 12.9 (16.2) | 2.7 (3.4) | 8.7 (10.9) | 3.3 (4.1) |

| 1950 | 154.8 (65.5) | 38.4 (16.3) | 7.1 (3.0) | 33.7 (14.3) | 2.3 (1.0) |

| 1960 | 296.4 (69.4) | 51.9 (12.1) | 16.2 (3.8) | 52.3 (12.2) | 10.7 (2.5) |

| 1970 | 617.2 (73.7) | 79.8 (9.5) | 20.3 (2.4) | 81.6 (9.7) | 38.4 (4.6) |

| 1980 | 1651.7 (73.6) | 177.6 (7.9) | 31.3 (1.4) | 198.5 (8.8) | 183.9 (8.2) |

| 1990 | 3351.7 (72.2) | 381.0 (8.2) | 49.1 (1.1) | 408.6 (8.8) | 452.4 (9.7) |

| 2000 | 5715.2 (71.6) | 715.0 (9.0) | 141.6 (1.8) | 876.4 (11.0) | 532.7 (6.7) |

| 2010 | 8093.9 (69.3) | 1059.3 (9.1) | 425.0 (3.6) | 1435.1 (12.3) | 661.9 (5.7) |

| 2015 | 9737.1 (67.8) | 1400.1 (9.8) | 663.6 (4.6) | 2049.9 (14.3) | 508.3 (3.5) |

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Labor’s share of national income rose from 1929 to the 1970s but fell each decade after. The share of income going to small businesses, called “proprietor’s income,” has declined over this period, but has stabilized at slightly under 10%. Rental income’s share fell from 1960 to 1990, but has since grown back to over 4%. The share accruing to corporate profits has increased in recent years to over 14%.

As Table 1 illustrates, the biggest fluctuations in income share have been associated with income from interest earned by individuals and firms, and are caused largely by changes in interest rates. It declined until 1960, then rose until the 1990s, before falling again in the last two decades.

Personal or Family Distribution of Income

personal or family distribution of income The distribution of income to individuals or family groups (typically quintiles, or fifths, of the population).

When most people use the expression “the distribution of income,” they typically mean personal or family distribution of income. This distributional measure is concerned with how much income, in percentage terms, goes to specific segments of the population.

To analyze personal and family income distribution, the Census Bureau essentially arrays households from the lowest incomes to the highest. It then splits these households into quintiles, or fifths, from the lowest 20% of households to the highest 20%. After totaling and averaging household incomes for each quintile, the Census Bureau computes the percentage of income flowing to each quintile.

Today, the United States contains approximately 125 million households. Therefore, the 25 million households with the lowest incomes compose the bottom quintile, and the 25 million households with the highest incomes compose the top quintile. Because much of the country’s income is concentrated at the top, the Census Bureau breaks down the highest quintile further, showing the percentage of income flowing to the richest 5% and 1% of the population.

Table 2 shows the official income distribution estimates for the United States since 1970. These estimates are based on money income before taxes and do not include the value of noncash benefits, such as food stamps, public housing, Medicaid, or employer-

| TABLE 2 | SHARE OF AGGREGATE INCOME RECEIVED BY EACH HOUSEHOLD QUINTILE: 1970– |

|||||||

| Year | Lowest | Second | Third | Fourth | Highest | Top 5% | Top 1% | Gini Coefficient |

| 1970 | 4.1 | 10.8 | 17.4 | 24.5 | 43.3 | 19.9 | 8.5 | 0.394 |

| 1975 | 4.4 | 10.5 | 17.1 | 24.8 | 43.2 | 20.1 | 8.2 | 0.397 |

| 1980 | 4.3 | 10.3 | 16.9 | 24.9 | 43.7 | 20.2 | 8.8 | 0.403 |

| 1985 | 4.0 | 9.7 | 16.3 | 24.6 | 45.3 | 23.0 | 11.2 | 0.419 |

| 1990 | 3.9 | 9.6 | 15.9 | 24.0 | 46.6 | 23.9 | 11.9 | 0.428 |

| 1995 | 3.7 | 9.1 | 15.2 | 23.3 | 48.7 | 25.5 | 12.2 | 0.450 |

| 2000 | 3.6 | 8.9 | 14.9 | 23.0 | 49.6 | 26.5 | 17.3 | 0.462 |

| 2005 | 3.4 | 8.6 | 14.6 | 23.0 | 50.4 | 27.1 | 17.4 | 0.469 |

| 2010 | 3.3 | 8.5 | 14.6 | 23.4 | 50.3 | 27.8 | 18.5 | 0.470 |

| 2014 | 3.1 | 8.2 | 14.3 | 23.2 | 51.2 | 29.2 | 19.3 | 0.480 |

Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office), 2015.

Note that if the income distribution were perfectly equal, all quintiles would receive 20% of aggregate income. A quick look at these income distributions over the past four decades suggests that our distribution of income has been growing more unequal. Specifically, the share of income received by the highest quintile has steadily risen since 1970, while the share of income received by each of the four other quintiles has steadily fallen since 1970. Even more notable is how the income flowing to the top 1% has increased the most, with that share of income more than doubling since 1970. Keep in mind that these numbers ignore taxes and transfers (direct payment to households such as welfare and food stamps) that temper income inequality somewhat.

Still, incomes of the richest Americans have fared best over the last generation, and one piece of evidence has been the meteoric rise in CEO salaries. Adjusting for inflation, the average salary of a CEO increased 8-

Compressing distribution data into quintiles allows us to see how distribution has evolved. Economists have developed two primary measures that allow comparisons to be drawn with ease across time and between countries. These measures are Lorenz curves and the Gini coefficient.

Lorenz Curves

Lorenz curve A graph showing the cumulative distribution of income or wealth. Households are measured on the horizontal axis while income or wealth is measured on the vertical axis.

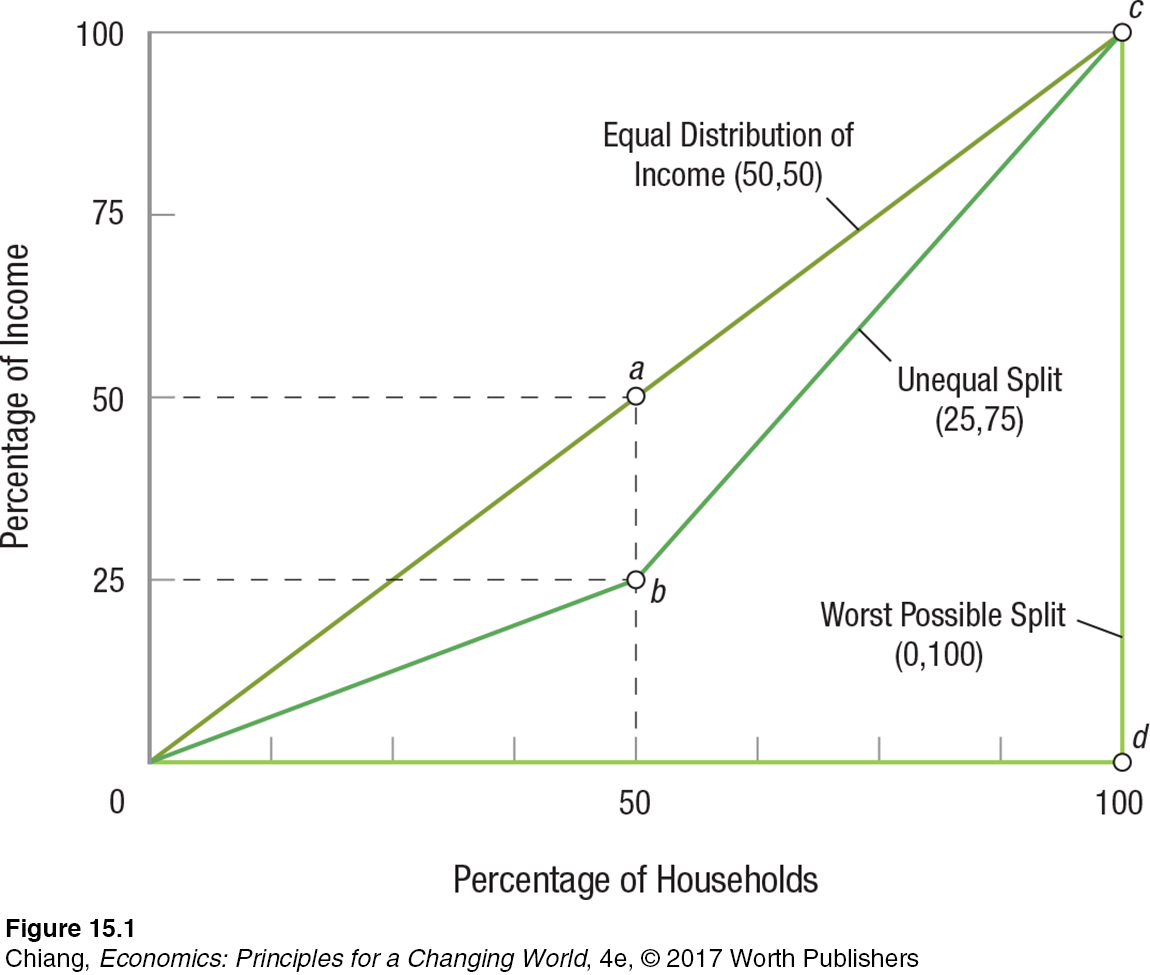

A Lorenz curve cumulates households of various income levels on the horizontal axis, and relates this to their cumulated share of total income on the vertical axis. Figure 1, for simplicity, shows a two-

The second curve in Figure 1 shows a two-

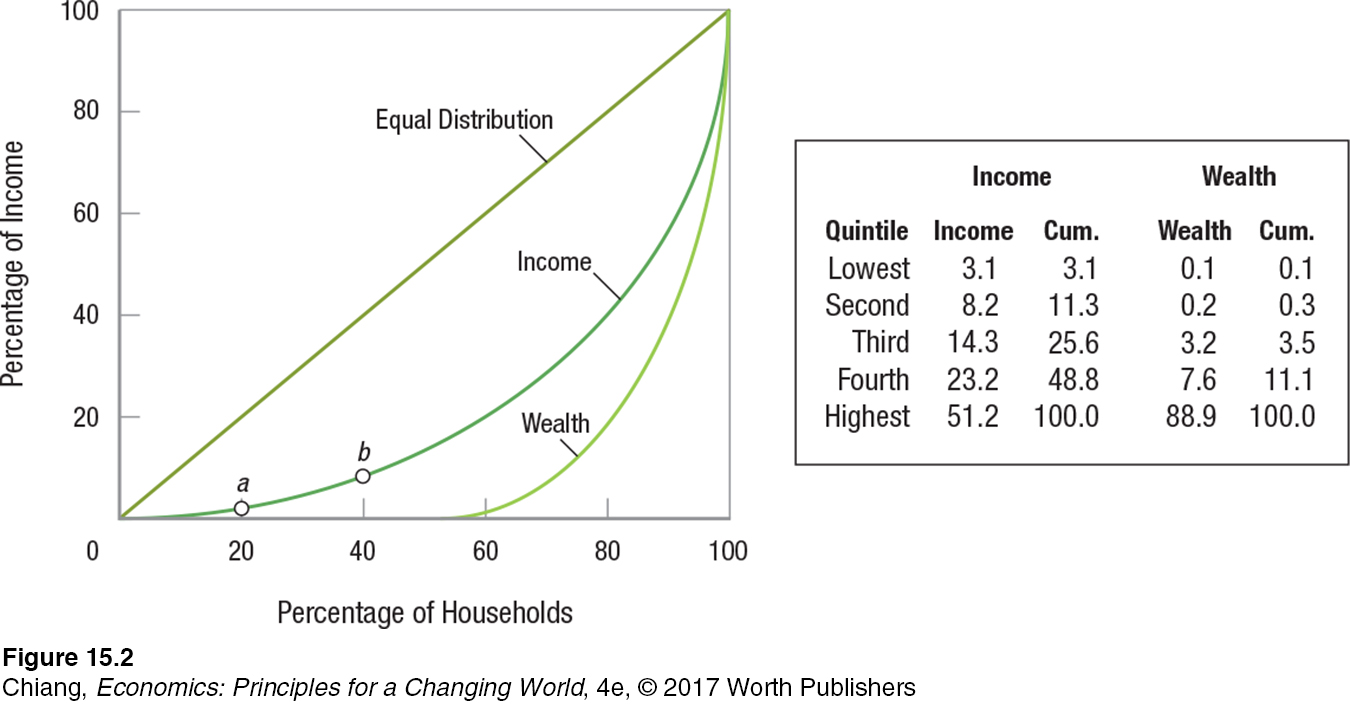

Figure 2 and its accompanying table offer more realistic Lorenz curves for income and wealth data for the United States in the year 2014. The quintile income distribution in the second column of the table is cumulated in the third column and plotted in Figure 2. (To cumulate a quintile means to add its percentage of income to the percentages earned by all lower quintiles.)

In Figure 2, for instance, the share of income received by the lowest fifth is 3.1%; it is plotted as point a. Next, the lowest two quintiles are summed (3.1 + 8.2 = 11.3) and plotted as point b. The process continues until all quintiles have been plotted to create the Lorenz curve.

Figure 2 also plots the Lorenz curve for wealth; it shows how wealth is much more unequally distributed than income. The wealthiest 20% of Americans control nearly 90% of wealth, even though they earn only half of all income.

Gini Coefficient

Gini coefficient A measure of income inequality defined as the area between the Lorenz curve and the equal distribution line divided by the total area below the equal distribution line.

Lorenz curves provide a good graphical summation of income (or wealth) distributions, but they can be inconvenient to use when comparing distributions between different countries or across time. Economists prefer to use one number to represent the inequality of an economy’s income (or wealth) distribution: the Gini coefficient.

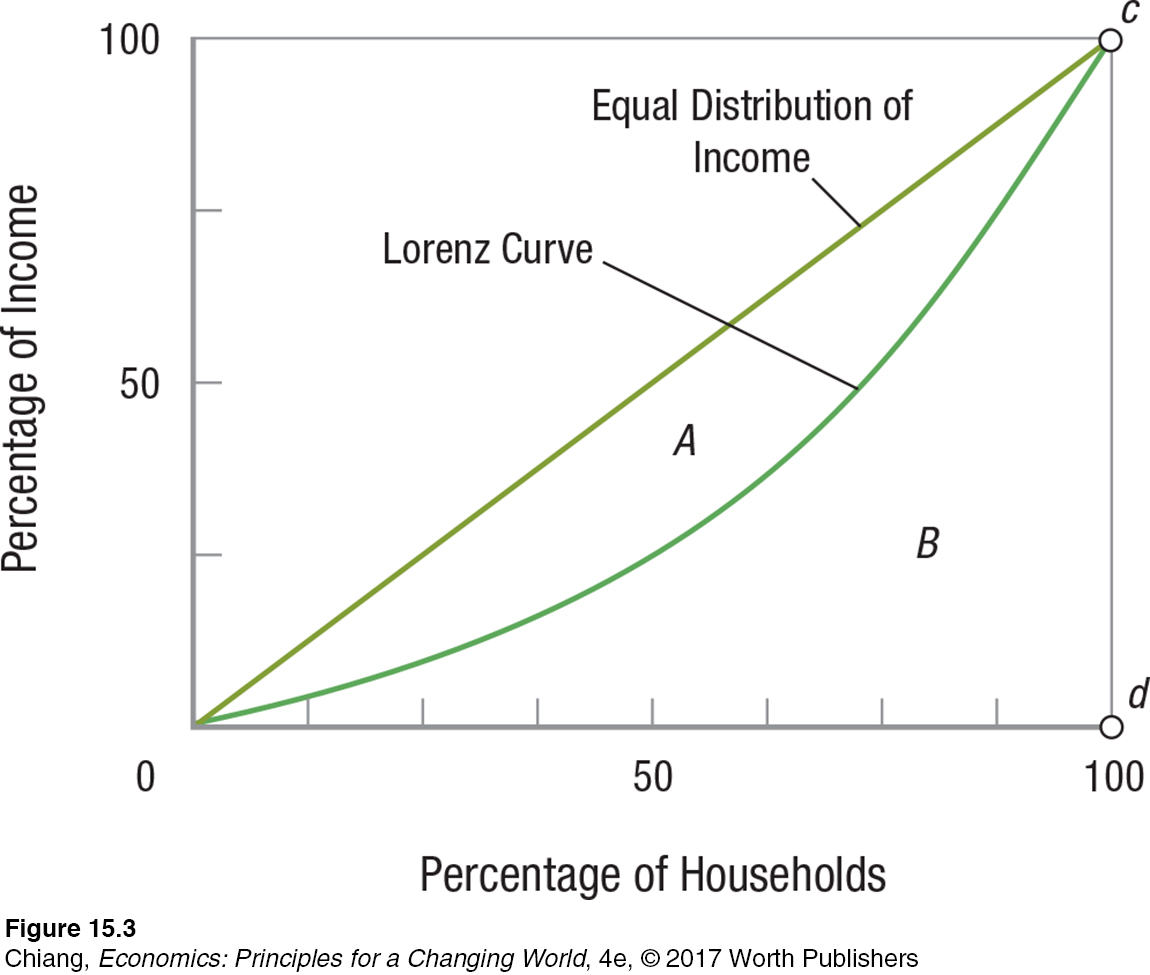

The Gini coefficient provides a measure of the position of the Lorenz curve. It is calculated by dividing the area between the Lorenz curve and the equal distribution line by the area below the equal distribution line. In Figure 3, the Gini coefficient is the ratio of area A to area (A + B).

If the distribution were equal, area A would disappear (equal zero); thus, the Gini coefficient would be zero. If the distribution were as unequal as possible, with one individual or household earning all national income, area B would disappear; thus, the Gini coefficient would be 1.

As a rule, the lower the coefficient, the more equal the distribution; the higher the coefficient, the more unequal. Looking back at the last column in Table 2, the Gini coefficient confirms that the basic income distribution has become more unequal since 1970. The Gini coefficient has risen from 0.394 in 1970 to 0.480 in 2014.

The Impact of Redistribution

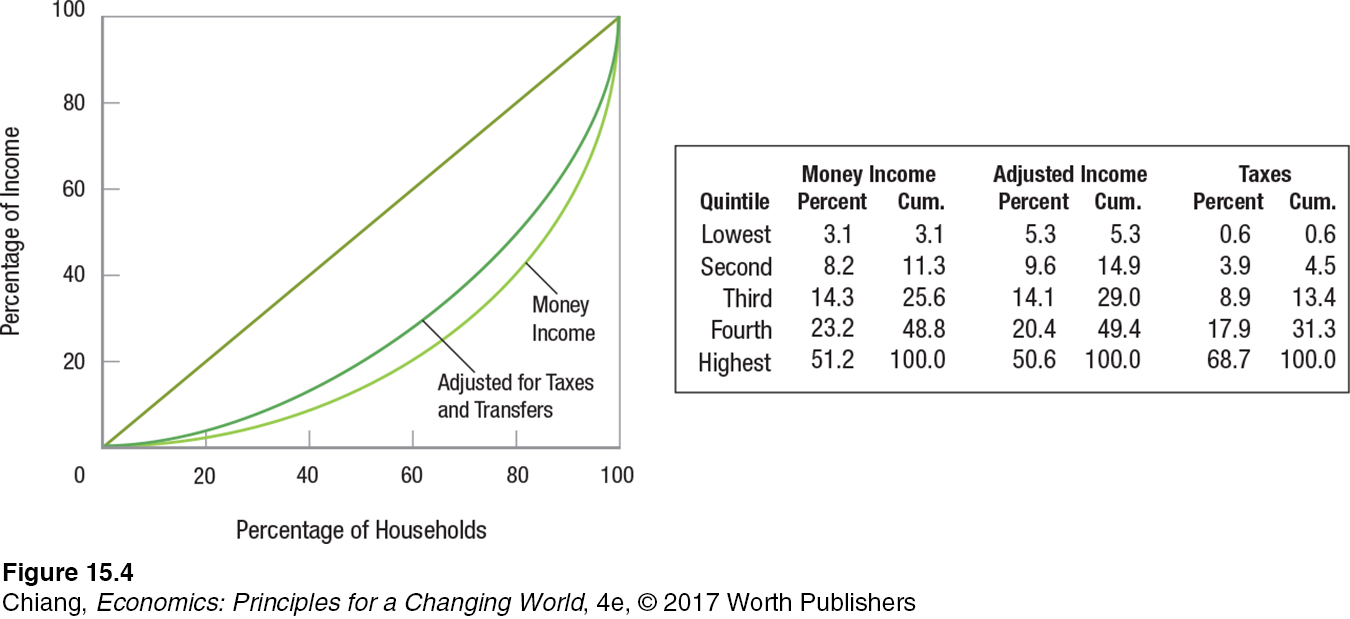

In the United States, there is a vast array of income redistribution policies, including the progressive income tax (where those with higher incomes pay a higher rate than those with lower incomes), housing subsidies, and other transfer payments such as Medicaid and Medicare, Social Security, and traditional welfare programs. Remember that the income distribution data in Table 2 excluded such government-

Figure 4 provides an estimate of the impact progressive taxes and transfer payments (cash and in-

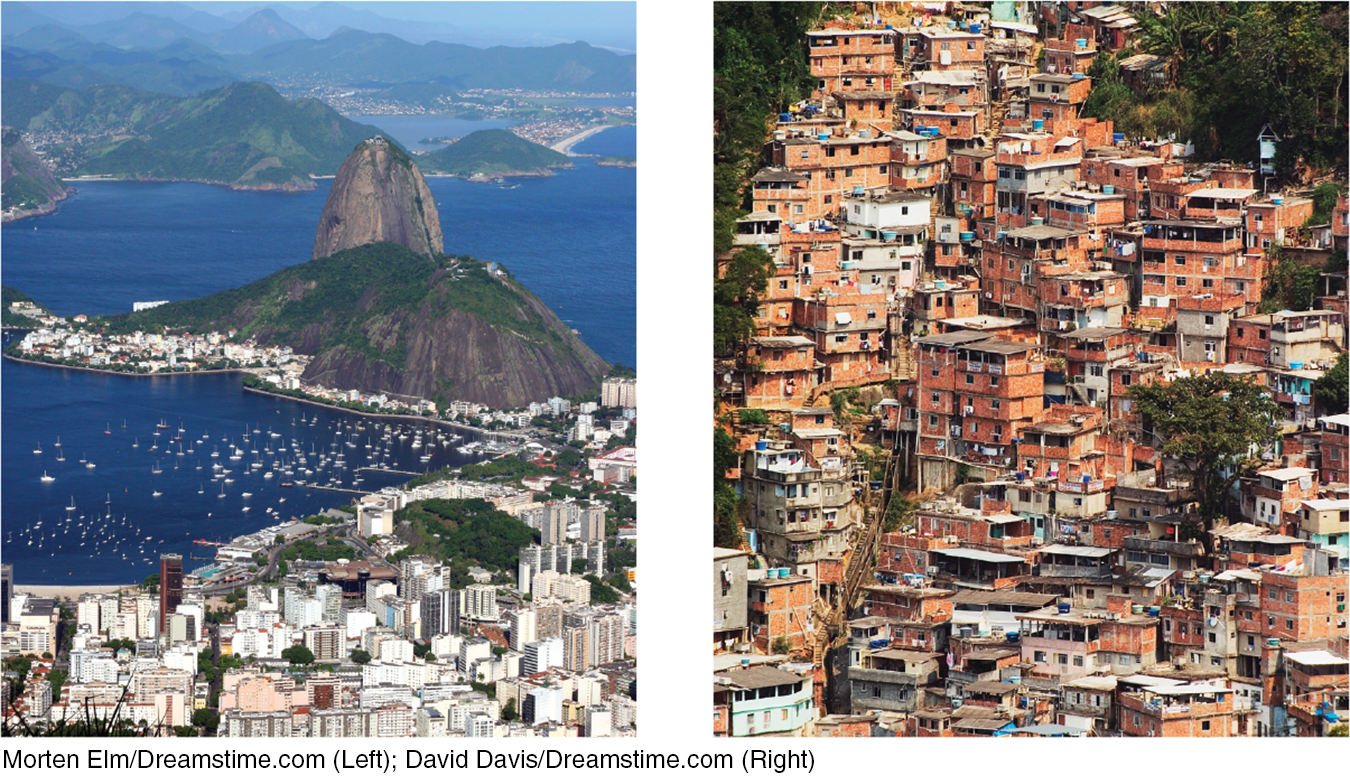

Table 3 provides some examples of how income distribution varies around the world. Income in European countries is generally more equally distributed than in the United States, while many South American countries have more unequal distributions.

| TABLE 3 | GINI COEFFICIENTS FOR VARIOUS COUNTRIES, 2014 | |||

| Country | Gini Coefficient | Country | Gini Coefficient | |

| Australia | 0.349 | Italy | 0.352 | |

| Bolivia | 0.481 | Japan | 0.321 | |

| Brazil | 0.529 | Mexico | 0.481 | |

| Canada | 0.337 | New Zealand | 0.362 | |

| Chile | 0.505 | South Africa | 0.634 | |

| China | 0.421 | Spain | 0.359 | |

| Denmark | 0.291 | Sweden | 0.273 | |

| France | 0.331 | United Kingdom | 0.326 | |

| Israel | 0.428 | United States | 0.480 | |

Data from World Bank, World Development Indicators (Washington, D.C.: World Bank), 2015.

Redistribution policies are the subject of intense debates. Those on the political right argue that differences in income are the natural result of a market system in which different individuals possess different personal endowments, schooling, and ambition. They believe, moreover, that the incentives of the marketplace are needed to encourage people to work and produce. The opportunities that markets provide mean that some people will be winners and others will lose. These analysts are unconcerned about the distribution of income unless it becomes so unequal that it discourages incentives and reduces efficiency.

Those on the political left argue that public policy should ultimately be guided by human needs. They see personal wealth as being the product of community effort as much as individual effort, and therefore they favor greater government taxation of income and wealth. By and large, European nations have found this argument more compelling than has the United States. This is reflected in the breadth of European social welfare policies. Because there is no correct answer (except possibly keeping distribution away from the extremes), this debate continues.

Causes of Income Inequality

Many factors contribute to income inequality in our society. First, as just mentioned, people are born into different circumstances with differing natural abilities. Families take varying interest in the well-

Human Capital The guarantee of a free public education through high school and huge subsidies to public colleges and universities for all Americans are designed to even out some of the economic differences among families. Still, public education does not eliminate the disparities. Some parents plan their children’s education long before they are born, while other parents ignore education altogether.

Table 4 provides evidence of the impact investments in education have on earnings. Those without high school diplomas earned the least, roughly a third less than high school graduates. A college degree resulted in mean earnings about 2.5 times higher than what individuals without high school diplomas earned.

| TABLE 4 | MEAN EARNINGS BY HIGHEST DEGREE EARNED, 2014 | |||

| Mean Earnings by Highest Degree | ||||

| No High School Diploma | High School Graduate | College Graduate | Advanced Degree | |

| All Persons | $25,376 | $34,736 | $57,252 | $72,072 |

| Male | 26,884 | 39,052 | 64,948 | 84,760 |

| Female | 21,268 | 30,056 | 50,180 | 61,620 |

| White | 25,636 | 36,192 | 58,864 | 72,280 |

| Black | 22,880 | 30,108 | 46,540 | 59,748 |

| Asian | 24,804 | 31,408 | 59,748 | 81,224 |

| Hispanic | 24,232 | 30,940 | 48,724 | 64,220 |

Data from U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The U.S. economy has become more technologically complex. Manufacturing jobs have dwindled, reducing the demand for these workers, reducing their real wages. Several decades ago, people with low education levels could find highly productive work in manufacturing, with good wages and benefits. Globalization and increased capital mobility, however, have caused many of these jobs to migrate to lower-

Our economy is increasingly oriented toward service industries, making investments in human capital more important than ever. The service industry spans more than just burger flipping, maid service, and landscaping. The United States is still the world leader in the design and development of new products, basic scientific research and development, and other professional services. All these industries and occupations have one thing in common: the need for highly skilled and highly educated employees.

Other Factors In an earlier chapter, we saw that economic discrimination leads to an income distribution skewed against those subject to discrimination. Reduced wages then reduce an individual’s incentive to invest in human capital because the returns are lower, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Table 5 outlines some characteristics of households occupying two different income quintiles. By comparing the lowest quintile with the highest, we can see some of the reasons for income inequality. As the Census Bureau summarizes these differences, “High-

| TABLE 5 | DISTRIBUTION OF HOUSEHOLDS BY SELECTED CHARACTERISTICS WITHIN INCOME QUINTILES, 2014 | |||

| Characteristic | Lowest Quintile | Highest Quintile | ||

| Type of Residence | ||||

| Inside metropolitan area | 81.4% | 90.7% | ||

| Inside principal city | 39.8 | 30.4 | ||

| Outside principal city | 41.6 | 60.3 | ||

| Outside metropolitan area | 18.6 | 9.3 | ||

| Type of Household | ||||

| Family households | 39.0 | 86.0 | ||

| Married- |

16.6 | 77.0 | ||

| Nonfamily households | 61.0 | 14.0 | ||

| Householder living alone | 57.0 | 6.8 | ||

| Age of Householder | ||||

| 15 to 34 years | 22.0 | 15.6 | ||

| 35 to 54 years | 26.1 | 49.7 | ||

| 55 to 64 years | 18.1 | 22.2 | ||

| 65 years or older | 33.8 | 12.5 | ||

| Number of Earners | ||||

| No earners | 61.5 | 3.1 | ||

| One earner | 34.2 | 20.9 | ||

| Two or more earners | 4.4 | 76.0 | ||

Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office), 2015.

The rise in two-

It is hardly surprising that households with two people working tend to have higher incomes than households with only one person or none working. In most households, whether one or two people work represents a choice. Today, clearly more couples are opting for two incomes. This is significant, given that rising income inequality is often cited as evidence that the United States needs to change its public policies to reduce inequalities. Yet, if the rise in inequality is due largely to changes in household attitudes toward work and income, with more couples choosing dual-

This overview of income distribution and inequality provides a broad foundation for the remainder of the chapter, which focuses on poverty, its causes, and possible cures.

ISSUE

How Much Do You Need to Earn to Be in the Top 1%?

Among the most contentious issues of the past decade has been the rising income and wealth of the richest Americans. Even during the depths of the Great Recession, average incomes of the richest 1% continued to rise, much to the angst of the rest of the population, many of whom had lost jobs or seen stagnant wages.

Still, the ability to work hard and achieve great wealth is engrained in the hopes of millions who dream to become part of the 1%. And each year, thousands of Americans reach this exclusive group for the first time. How much does one need to earn in order to be included among the top 1%? In 2015 the minimum annual income was approximately $500,000. Although this is a tremendous amount of money, remember that it’s the minimum income required to be in the top 1%. The average income of the top 1% is over $1.3 million per year!

The minimum income to be in the top 1% also varies by state, as shown in the table. In Connecticut, one must earn at least $677,608 to be among the top 1% of income earners, while in Arkansas, it only requires $228,298. Do you think these amounts are unattainable without a rich uncle leaving you millions to jumpstart a lucrative business? Not quite. Only 2 in 5 members of the 1% inherited wealth. The vast majority of those in the 1% are highly educated, motivated individuals who pursue lucrative careers or take chances to build successful businesses. Pursuing a college degree is certainly an important step along the way.

| MINIMUM INCOME FOR THE TOP 1% (TOP 5 AND BOTTOM 5 STATES, INCLUDING THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA) | |||

| 1. Connecticut | $677,608 | 47. Mississippi | $262,809 |

| 2. District of Columbia | 555,341 | 48. Kentucky | 262,653 |

| 3. New Jersey | 538,666 | 49. West Virginia | 242,774 |

| 4. Massachusetts | 532,328 | 50. New Mexico | 240,847 |

| 5. New York | 506,051 | 51. Arkansas | 228,298 |

Data from CNN Money, January 27, 2015.

CHECKPOINT

THE DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME AND WEALTH

The functional distribution of income splits income among factors of production.

The family or personal distribution of income typically splits income into quintiles.

A Lorenz curve cumulates households of various income levels on the horizontal axis and their cumulative share of income on the vertical axis.

The Gini coefficient is the ratio of the area between the Lorenz curve and the equal distribution line to the total area below the equal distribution line. It is used to compare income distribution across time and between countries.

Income redistribution activities such as progressive taxes, Medicare, Medicaid, and other transfer and welfare programs reduce the Gini coefficient and reduce the inequality in the distribution of income.

Income inequality is caused by a number of factors, including individual investment in human capital, natural abilities, and discrimination.

QUESTION: Suppose that a proposal is made to streamline the role of government by reducing the bureaucracy of social income programs. For example, the government would eliminate Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other welfare programs, and instead simply give $10,000 a year to every citizen over the age of 18. Would this improve the income distribution in the United States? Why or why not?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Because $10,000 a year per person represents a substantial amount of money to those in the lowest income brackets, it would clearly improve (make more equal) the before-