Chapter Introduction

| CHAPTER |

| 16 |

Personality Disorders

TOPIC OVERVIEW

Paranoid Personality Disorder

Schizoid Personality Disorder

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Borderline Personality Disorder

Histrionic Personality Disorder

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Avoidant Personality Disorder

Dependent Personality Disorder

Obsessive-

The “Big Five” Theory of Personality and Personality Disorders

“Personality Disorder—

While interviewing for the job of editor of a start-

A year later, many of the same individuals were describing Frederick differently—

To be sure, Frederick had great charm, and he knew how to make others feel important, when it served his purpose. Thus he always had his share of friends and admirers. But in reality they were just passing through, until Frederick would tire of them or feel betrayed by their lack of enthusiasm for one of his self-

Bright and successful though he was, Frederick always felt entitled to more than he was receiving—

Each of us has a personality—a set of uniquely expressed characteristics that influence our behaviors, emotions, thoughts, and interactions. Our particular characteristics, often called personality traits, lead us to react in fairly predictable ways as we move through life. Yet our personalities are also flexible. We learn from experience. As we interact with our surroundings, we try out various responses to see which feel better and which are more effective. This is a flexibility that people who suffer from a personality disorder usually do not have.

People with a personality disorder display an enduring, rigid pattern of inner experience and outward behavior that impairs their sense of self, emotional experiences, goals, capacity for empathy, and/or capacity for intimacy (APA, 2013) (see Table 16-1). Put another way, they have personality traits that are much more extreme and dysfunctional than those of most other people in their culture, leading to significant problems and psychological pain for themselves or others.

personality disorder An enduring, rigid pattern of inner experience and outward behavior that repeatedly impairs a person’s sense of self, emotional experiences, goals, capacity for empathy, and/or capacity for intimacy.

personality disorder An enduring, rigid pattern of inner experience and outward behavior that repeatedly impairs a person’s sense of self, emotional experiences, goals, capacity for empathy, and/or capacity for intimacy.

|

Personality Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual displays a long- |

|

2. |

The individual’s pattern is significantly different from ones usually found in his or her culture. |

|

3. |

Individual experiences significant distress or impairment. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

Frederick appears to display a personality disorder. For most of his life, his extreme narcissism, grandiosity, and insensitivity have led to poor functioning in both the personal and social realms. They have caused him to repeatedly feel angry and unappreciated, deprived him of close personal relationships, and brought considerable pain to others. Witness the upset and turmoil felt by Frederick’s coworkers and girlfriends.

The symptoms of personality disorders last for years and typically become recognizable in adolescence or early adulthood, although some start during childhood (APA, 2013; Westen et al., 2011). These disorders are among the most difficult psychological disorders to treat. Many people with the disorders are not even aware of their personality problems and fail to trace their difficulties to their maladaptive style of thinking and behaving. Surveys indicate that between 10 and 15 percent all adults in the United States have a personality disorder (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011).

It is common for a person with a personality disorder to also suffer from another disorder, a relationship called comorbidity. As you will see later in this chapter, for example, many people with avoidant personality disorder, who fearfully shy away from all relationships, also display social anxiety disorder. Perhaps avoidant personality disorder predisposes people to develop social anxiety disorder. Or perhaps social anxiety disorder sets the stage for the personality disorder. Then again, some biological factor may create a predisposition to both the personality disorder and the anxiety disorder. Whatever the reason for the relationship, research indicates that the presence of a personality disorder complicates a person’s chances for a successful recovery from other psychological problems (Fok et al., 2014; Abbass et al., 2011).

DSM-

These 10 personality disorders are each characterized by a group of problematic personality symptoms. For example, as you will soon see, paranoid personality disorder is diagnosed when a person has unjustified suspicions that others are harming him or her, has persistent unfounded doubts about the loyalty of friends, reads threatening meanings into benign events, persistently bears grudges, and has recurrent unjustified suspicions about the faithfulness of life partners.

The DSM’s listing of 10 distinct personality disorders is called a categorical approach. Like a light switch that is either on or off, this kind of approach assumes that (1) problematic personality traits are either present or absent in people, (2) a personality disorder is either displayed or not displayed by a person, and (3) a person who suffers from a personality disorder is not markedly troubled by personality traits outside of that disorder.

It turns out, however, that these assumptions are frequently contradicted in clinical practice. In fact, the symptoms of the personality disorders listed in DSM-

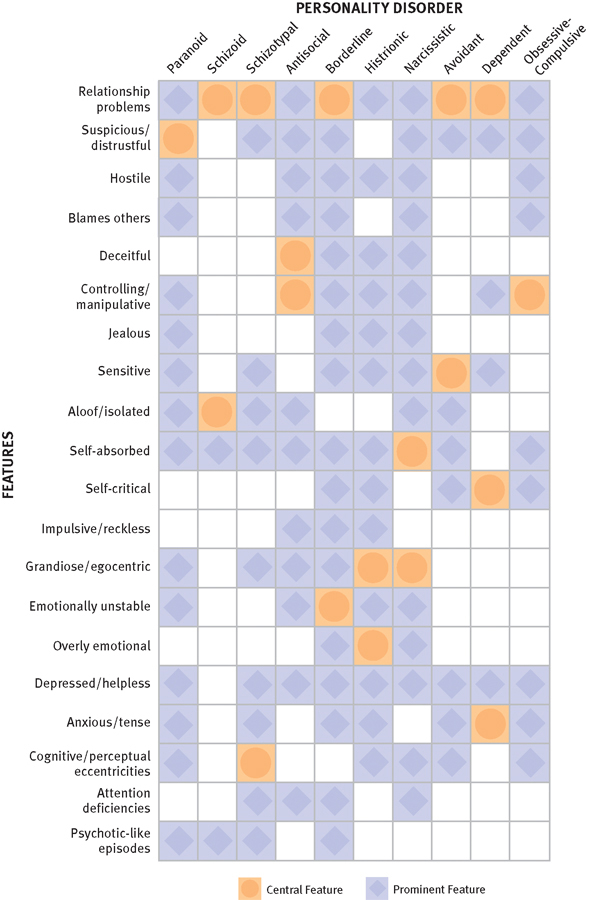

Prominent and central features of the personality disorders in DSM-

The symptoms of the various personality disorders often have significant overlap, leading to frequent misdiagnoses or to multiple diagnoses for a given client.

Given this state of affairs, many theorists have challenged the use of a categorical approach to personality disorders. They believe that personality disorders differ more in degree than in type of dysfunction and should instead be classified by the severity of personality traits rather than by the presence or absence of specific traits—

Given the inadequacies of a categorical approach and the growing enthusiasm for a dimensional one, the framers of DSM-

Most of the discussions in this chapter are organized around the 10-

Why do you think personality disorders are particularly subject to so many efforts at amateur psychology?

As you read about the various personality disorders, you should be clear that diagnoses of such disorders can be assigned too often. We may catch glimpses of ourselves or of people we know in the descriptions of these disorders and be tempted to conclude that we or they have a personality disorder. In the vast majority of instances, such interpretations are incorrect. We all display personality traits. Only occasionally are they so maladaptive, distressful, and inflexible that they can be considered disorders.