7.2 What Causes Unipolar Depression?

Episodes of unipolar depression often seem to be triggered by stressful events (Fisher et al., 2012; Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011). In fact, researchers have found that depressed people have a larger number of stressful life events during the month just before the onset of their disorder than do other people during the same period of time. Of course, stressful life events also precede other psychological disorders, but depressed people often report more such events than anybody else.

Some clinicians consider it important to distinguish a reactive (exogenous) depression, which follows clear-

Why do you think stressful events or periods in life might trigger depressed feelings and other negative emotions?

The current explanations of unipolar depression point to biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Just as clinicians now recognize both internal and situational features in each case of depression, many believe that the various explanations should be viewed collectively for unipolar depression to be understood fully.

The Biological View

Medical researchers have been aware for years that certain diseases and drugs produce mood changes. Could unipolar depression itself have biological causes? Evidence from genetic, biochemical, anatomical, and immune system studies suggests that often it does.

Genetic FactorsFour kinds of research—

If a predisposition to unipolar depression is inherited, you might also expect to find a particularly large number of cases among the close relatives of a proband. Twin studies have supported this expectation (Levinson & Nichols, 2014). One study looked at nearly 200 pairs of twins. When a monozygotic (identical) twin had unipolar depression, there was a 46 percent chance that the other twin would have the same disorder. In contrast, when a dizygotic (fraternal) twin had unipolar depression, the other twin had only a 20 percent chance of developing the disorder (McGuffin et al., 1996).

|

|

One- |

Female- |

Typical Age at Onset (Years) |

Prevalence Among First- |

Percentage Receiving Currently Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Major depressive disorder |

8.0 |

2:1 |

24– |

Elevated |

50.0 |

|

Persistent depressive disorder (with dysthymic syndrome) |

1.5– |

Between 3:2 and 2:1 |

10– |

Elevated |

36.8 |

|

Bipolar I disorder |

1.6 |

1:1 |

15– |

Elevated |

33.8 |

|

Bipolar II disorder |

1.0 |

1:1 |

15– |

Elevated |

33.8 |

|

Cyclothymic disorder |

0.4 |

1:1 |

15– |

Elevated |

Unknown |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Information from: González et al., 2010;Taube- |

|||||

BETWEEN THE LINES

Medical Problems and Depression

|

50% |

Stroke victims who experience clinical depression |

|

30% |

Cancer patients who experience depression |

|

20% |

Heart attack victims who become depressed |

|

18% |

People with diabetes who are depressed |

|

(Udesky, 2014; Jiang et al., 2011; Kerber et al., 2011; NIMh, 2004) |

|

Adoption studies have also implicated a genetic factor, at least in cases of severe unipolar depression. One study looked at the families of adopted persons who had been hospitalized for this disorder in Denmark. The biological parents of these adoptees turned out to have a higher incidence of severe depression (but not mild depression) than did the biological parents of a control group of nondepressed adoptees (Levinson & Nichols, 2014; Kamali & McInnis, 2011). Some theorists interpret these findings to mean that severe depression is more likely than mild depression to be caused by genetic factors.

Finally, today’s scientists have at their disposal techniques from the field of molecular biology to help them directly identify genes and determine whether certain gene abnormalities are related to depression. Using such techniques, researchers have found evidence that unipolar depression may be tied to genes on chromosomes 1, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, and X (Preuss et al., 2013; Kamali & McInnis, 2011). For example, a number of researchers have found that people who are depressed often have an abnormality of their 5-

Biochemical FactorsLow activity of two neurotransmitter chemicals, norepinephrine and serotonin, has been strongly linked to unipolar depression. In the 1950s, several pieces of evidence began to point to this relationship. First, medical researchers discovered that reserpine and other medications for high blood pressure often caused depression (Ayd, 1956). As it turned out, some of these medications lowered norepinephrine activity and others lowered serotonin. A second piece of evidence was the discovery of the first truly effective antidepressant drugs. Although these drugs were discovered by accident, researchers soon learned that they relieve depression by increasing either norepinephrine or serotonin activity.

norepinephrine A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression and panic disorder.

norepinephrine A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression and panic disorder.

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive-

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive-

For years it was thought that low activity of either norepinephrine or serotonin was capable of producing depression, but investigators now believe that their relation to depression is more complicated (Ding et al., 2014; Goldstein et al., 2011). Research suggests that interactions between serotonin and norepinephrine activity, or between these and other kinds of neurotransmitters in the brain, rather than the operation of any one neurotransmitter alone, may account for unipolar depression. Some studies hint, for example, that depressed people have an overall imbalance in the activity of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and acetylcholine. In a variation of this theory, some researchers believe that serotonin is actually a neuromodulator, a chemical whose primary function is to increase or decrease the activity of other key neurotransmitters. If so, perhaps low serotonin activity serves to disrupt the activity of the other neurotransmitters, resulting in depression.

Biological researchers have also learned that the body’s endocrine system may play a role in unipolar depression (Treadway & Pizzagalli, 2014). As you have seen, endocrine glands throughout the body release hormones, chemicals that in turn spur body organs into action (see Chapter 6). People with unipolar depression have been found to have abnormally high levels of cortisol, one of the hormones released by the adrenal glands during times of stress (Marchand et al., 2014; Owens et al., 2014). This relationship is not all that surprising, given that stressful events often seem to trigger depression. Another hormone that has been tied to depression is melatonin, sometimes called the “Dracula hormone” because it is released only in the dark.

Still other biological researchers are starting to believe that unipolar depression is tied more closely to what happens within neurons than to the chemicals that carry messages between neurons. They believe that activity by key neurotransmitters or hormones ultimately leads to deficiencies of certain proteins and other chemicals within neurons, particularly to deficiencies of brain-

The biochemical explanations of unipolar depression have produced much enthusiasm, but research in this area has certain limitations. Some of it has relied on analogue studies, which create depression-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Serious Oversight

Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians fail to detect depression in at least 50 percent of their depressed patients (Culpepper & Johnson, 2011; Mitchell et al., 2011).

Brain Anatomy and Brain CircuitsIn Chapters 5 and 6, you read that many biological researchers now believe that the root cause of psychological disorders involves more than just a single neurotransmitter or single brain area. They have determined that emotional reactions of various kinds are tied to brain circuits—networks of brain structures that work together, triggering each other into action and producing a particular kind of emotional reaction. It appears that one brain circuit is tied largely to generalized anxiety disorder, another to panic disorder, and yet another to obsessive-

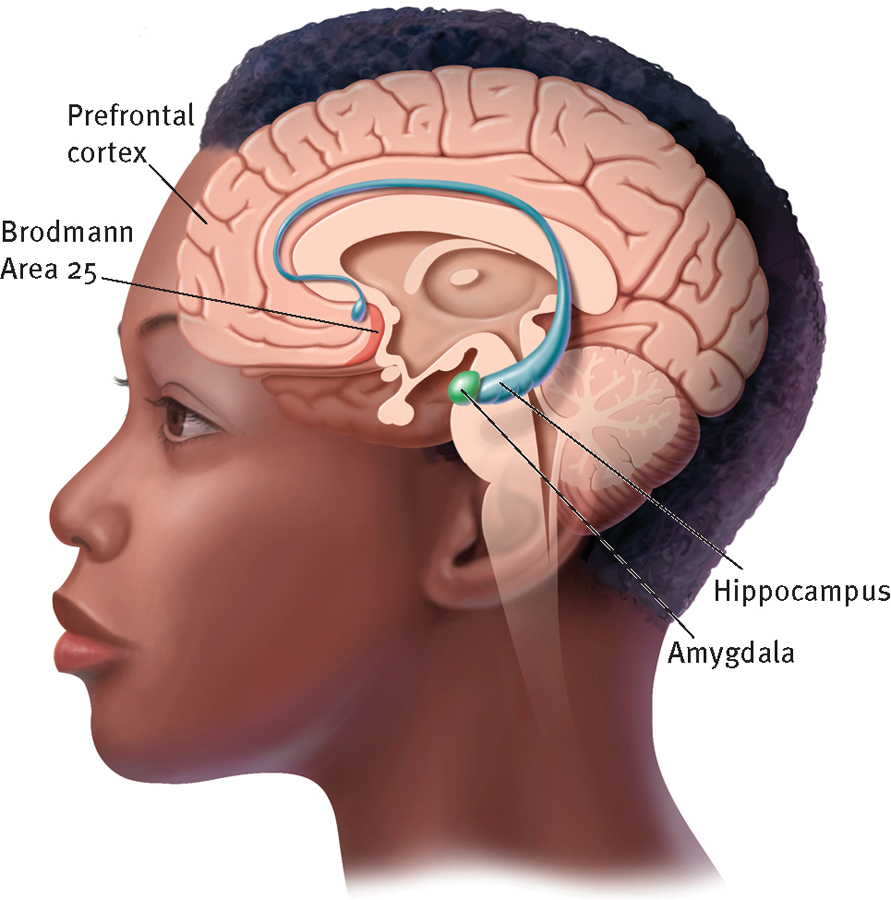

The biology of depression

Researchers believe that the brain circuit involved in unipolar depression includes the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, the amygdala, and Brodmann Area 25.

The prefrontal cortex is located within the frontal cortex of the brain. Because it receives information from a number of other brain areas, the prefrontal cortex is involved in many important functions, including mood, attention, and immune functioning. Several imaging studies have found lower activity and blood flow in the prefrontal cortex of depressed research participants than in the prefrontal cortex of nondepressed people (Vialou et al., 2014). However, other studies, focusing on select areas of the prefrontal cortex, have found increases in activity during depression (Lemogne et al., 2010; Drevets, 2001, 2000). Correspondingly, research finds that the prefrontal cortex activity of depressed individuals increases after successful treatment by some antidepressant drugs, but decreases after successful treatment by other kinds of antidepressant drugs (Cook & Leuchter, 2001). Given these varied findings, researchers currently believe that the prefrontal cortex plays a critical role in depression but that the specific nature of this role has yet to be clearly defined (Treadway & Pizzagalli, 2014; Goldstein et al., 2011).

The prefrontal cortex has strong neural connections with another part of the depression brain circuit, the hippocampus. Indeed, messages are both sent and received between the two brain areas. The hippocampus is one of the few brain areas to produce new neurons throughout adulthood, an activity known as neurogenesis. Several studies indicate that such hippocampal neurogenesis decreases dramatically when a person becomes depressed (Kubera et al., 2011; Airan et al., 2007). Correspondingly, when depressed people are successfully treated by antidepressant drugs, neurogenesis in the hippocampus returns to normal (Malberg & Schechter, 2005). Moreover, some imaging studies have detected a reduction in the size of the hippocampus among depressed persons (Goldstein et al., 2011; Campbell et al., 2004). Recall from Chapter 6 that the hippocampus helps to control the brain’s and body’s reactions to stress and plays a role in the formation and recall of emotional memories. Thus, its role in depression is not surprising.

You may also recall from Chapters 5 and 6 that the amygdala is a brain area that repeatedly seems to be involved in the expression of negative emotions and memories. It has been found to be a key area in each of the brain circuits tied to generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Apparently, it also plays a role in depression (Treadway & Pizzagalli, 2014). PET and f MRI scans indicate that there is 50 percent more activity and blood flow in the amygdala among depressed persons than among nondepressed persons (Goldstein et al., 2011; Drevets, 2001). In fact, one study suggests that as a patient’s depression increases in severity, the activity in his or her amygdala increases proportionately (Abercrombie et al., 1998). Moreover, among nondepressed research participants, activity in the amygdala increases as they are looking at pictures of sad faces; and among depressed participants, amygdala activity increases when they recall sad moments in their lives (Liotti et al., 2002; Drevets, 2000).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Football Injuries and Depression

According to a study of 2,500 retired National Football League players, those who suffer three concussions during their careers are three times more likely later to develop a depressive disorder than those who had no concussions.

Players who experience one or two concussions are 1.5 times more likely than other players to develop a depressive disorder.

Around 26 percent of all former professional football players have suffered three or more concussions.

(Schwarz, 2010; Mcconnaughey, 2007)

The fourth part of the depression brain circuit, Brodmann Area 25, has received enormous attention over the past 15 years (Eggers, 2014; Schiferle, 2013; Mayberg et al., 2005, 2000, 1997). This area tends to be smaller in depressed people than in nondepressed people. Moreover, like the amygdala, it is significantly more active among depressed people than among nondepressed people. In fact, brain scans reveal that when a person’s depression subsides, the activity in his or her Area 25 decreases significantly. Because activation of Area 25 comes and goes with episodes of depression, some theorists believe that it may in fact be a “depression switch,” a kind of junction box whose malfunction might be necessary and sufficient for depression to occur.

The Immune SystemAs you will see in Chapter 10, the immune system is the body’s network of activities and body cells that fight off bacteria, viruses, and other foreign invaders. When people are under intense stress for a while, their immune systems may become dysregulated, leading to lower functioning of important white blood cells called lymphocytes and to increased production of C-

The support for an immune system explanation of depression is circumstantial but compelling (Anderson et al., 2014; Sperner-

It is not yet clear how to interpret the relationship between depression and immune system dysregulation. It could be that such dysregulation and chronic inflammation cause depression, just as they help produce other illnesses. Or perhaps depression is itself a stressor that leads to immune system problems. A number of researchers are now conducting studies that should help clarify this relationship in the coming years.

Psychological Views

The psychological models that have been most widely applied to unipolar depression are the psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive models. The psychodynamic explanation has not been strongly supported by research, and the behavioral view has received only modest support. In contrast, cognitive explanations have received considerable research support and have gained a large following.

The Psychodynamic ViewSigmund Freud (1917) and his student Karl Abraham (1916, 1911) developed the first psychodynamic explanation of depression. They began by noting the similarity between clinical depression and grief in people who lose loved ones: constant weeping, loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping, loss of pleasure in life, and general withdrawal.

According to Freud and Abraham, a series of unconscious processes is set in motion when a loved one dies. Unable to accept the loss, mourners at first regress to the oral stage of development, the period of total dependency when infants cannot distinguish themselves from their parents. By regressing to this stage, the mourners merge their own identity with that of the person they have lost, and so symbolically regain the lost person. In this process, called introjection, they direct all their feelings for the loved one, including sadness and anger, toward themselves.

For most mourners, introjection is temporary. For some, however, grief worsens over time. They feel empty, they continue to avoid social relationships, and their sense of loss increases. They become depressed. Freud and Abraham believed that two kinds of people are particularly likely to become clinically depressed in the face of loss: those whose parents failed to nurture them and meet their needs during the oral stage and those whose parents gratified those needs excessively. Infants whose needs are inadequately met remain overly dependent on others throughout their lives, feel unworthy of love, and have low self-

Why do you think so many comedians and other entertainers report that they have grappled with depression earlier in their lives?

Of course, many people become depressed without losing a loved one. To explain why, Freud proposed the concept of symbolic, or imagined, loss, in which a person equates other kinds of events with the loss of a loved one. A college student may, for example, experience failure in a calculus course as the loss of her parents, believing that they love her only when she excels academically.

symbolic loss According to Freudian theory, the loss of a valued object (for example, a loss of employment) that is unconsciously interpreted as the loss of a loved one. Also called imagined loss.

symbolic loss According to Freudian theory, the loss of a valued object (for example, a loss of employment) that is unconsciously interpreted as the loss of a loved one. Also called imagined loss.

Although many psychodynamic theorists have parted company with Freud and Abraham’s theory of depression, it continues to influence current psychodynamic thinking (Desmet, 2013; Zuckerman, 2011). For example, object relations theorists (the psychodynamic theorists who emphasize relationships) propose that depression results when people’s relationships leave them feeling unsafe and insecure (Schattner & Sharar, 2011; Allen et al., 2004; Blatt, 2004). People whose parents pushed them toward either excessive dependence or excessive self-

The following description by the therapist of a depressed middle-

Marie Carls … had always felt very attached to her mother. … She always tried to placate her volcanic [emotions], to please her in every possible way. …

After marriage [to Julius], she continued her pattern of submission and compliance. Before her marriage she had difficulty in complying with a volcanic mother, and after her marriage she almost automatically assumed a submissive role. …

[W]hen she was thirty years old … [Marie] and her husband invited Ignatius, who was single, to come and live with them. Ignatius and [Marie] soon discovered that they had an attraction for each other. They both tried to fight that feeling; but when Julius had to go to another city for a few days, the so-

Her suffering had become more acute as she [came to believe] that old age was approaching and she had lost all her chances. Ignatius remained as the memory of lost opportunities. … Her life of compliance and obedience had not permitted her to reach her goal. … When she became aware of these ideas, she felt even more depressed. … She felt that everything she had built in her life was false or based on a false premise.

(Arieti & Bemporad, 1978, pp. 275-

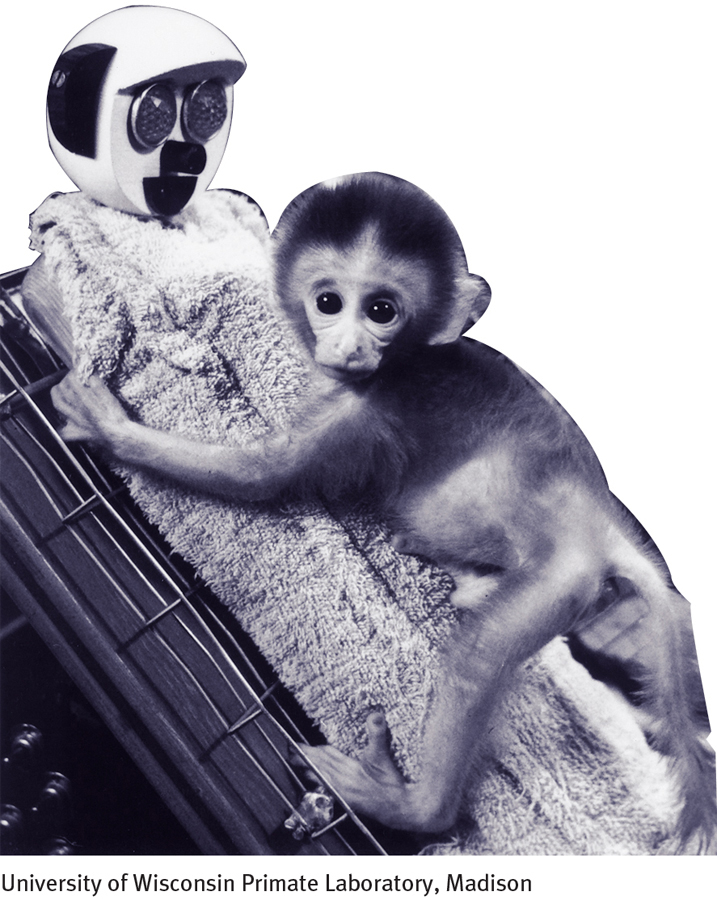

Studies have offered general support for the psychodynamic idea that depression may be triggered by a major loss. In a famous study of 123 infants who were placed in a nursery after being separated from their mothers, René Spitz (1946, 1945) found that 19 of the infants became very weepy and sad upon separation and withdrew from their surroundings—

anaclitic depression A pattern of depressed behavior found among very young children that is caused by separation from one’s mother.

anaclitic depression A pattern of depressed behavior found among very young children that is caused by separation from one’s mother.

Other research, involving both human participants and animal subjects, suggests that losses suffered early in life may set the stage for later depression (Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011; Pryce et al., 2005). When, for example, a depression scale was administered to 1,250 medical patients during visits to their family physicians, the patients whose fathers had died during their childhood scored higher on depression (Barnes & Prosen, 1985).

Related research supports the psychodynamic idea that people whose childhood needs were improperly met are particularly likely to become depressed after experiencing loss (Gonzalez et al., 2012; Goodman, 2002). In some studies, depressed patients have filled out a scale called the Parental Bonding Instrument, which indicates how much care and protection people feel they received as children. Many have identified their parents’ child-

These studies offer some support for the psychodynamic view of unipolar depression, but this support has key limitations. First, although the findings indicate that losses and inadequate parenting sometimes relate to depression, they do not establish that such factors are typically responsible for the disorder. In the studies of young children and young monkeys, for example, only some of the research participants who were separated from their mothers showed depressive reactions. In fact, it is estimated that less than 10 percent of all people who have major losses in life actually become depressed (Bonanno, 2004; Paykel & Cooper, 1992). Second, many findings are inconsistent. Though some studies find evidence of a relationship between childhood loss and later depression, others do not. Finally, certain features of the psychodynamic explanation are nearly impossible to test. Because symbolic loss is said to operate at an unconscious level, for example, it is difficult for researchers to determine if and when it is occurring.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Parental Impact

It has been estimated that 400,000 infants are born each year to depressed mothers (Murray & Nyp, 2011).

The Behavioral ViewBehaviorists believe that unipolar depression results from significant changes in the number of rewards and punishments people receive in their lives (Dygdon & Dienes, 2013; Martell et al., 2010). Clinical researcher Peter Lewinsohn was one of the first clinical theorists to develop a behavioral explanation (Lewinsohn et al., 1990, 1984). He suggested that the positive rewards in life dwindle for some people, leading them to perform fewer and fewer constructive behaviors. The rewards of campus life, for example, disappear when a young woman graduates from college and takes a job; and an aging baseball player loses the rewards of high salary and adulation when his skills deteriorate. Although many people manage to fill their lives with other forms of gratification, some become particularly disheartened. The positive features of their lives decrease even more, and the decline in rewards leads them to perform still fewer constructive behaviors. In this manner, they spiral toward depression.

In a number of studies, behaviorists have found that the number of rewards people receive in life is indeed related to the presence or absence of depression. Not only do depressed participants typically report fewer positive rewards than nondepressed participants, but when their rewards begin to increase, their mood improved as well (Bylsma et al., 2011; Lewinsohn, Youngren, & Grosscup, 1979). Similarly, other investigations have found a strong relationship between positive life events and feelings of life satisfaction and happiness (Carvalho & Hopko, 2011; Martell et al., 2010).

Lewinsohn and other behaviorists have further proposed that social rewards are particularly important in the downward spiral of depression (Martell et al., 2010; Farmer & Chapman, 2008). This claim has been supported by research showing that depressed persons receive fewer social rewards than nondepressed persons and that as their mood improves, their social rewards increase (see MindTech below). Although depressed people are sometimes the victims of social circumstances, it may also be that their dark mood and flat behaviors help produce a decline in social rewards (Joiner, 2002; Coyne, 2001).

Behaviorists have done an admirable job of compiling data to support this theory but their research, too, has limitations. It has relied heavily on the self-

MindTech

Texting: A Relationship Buster?

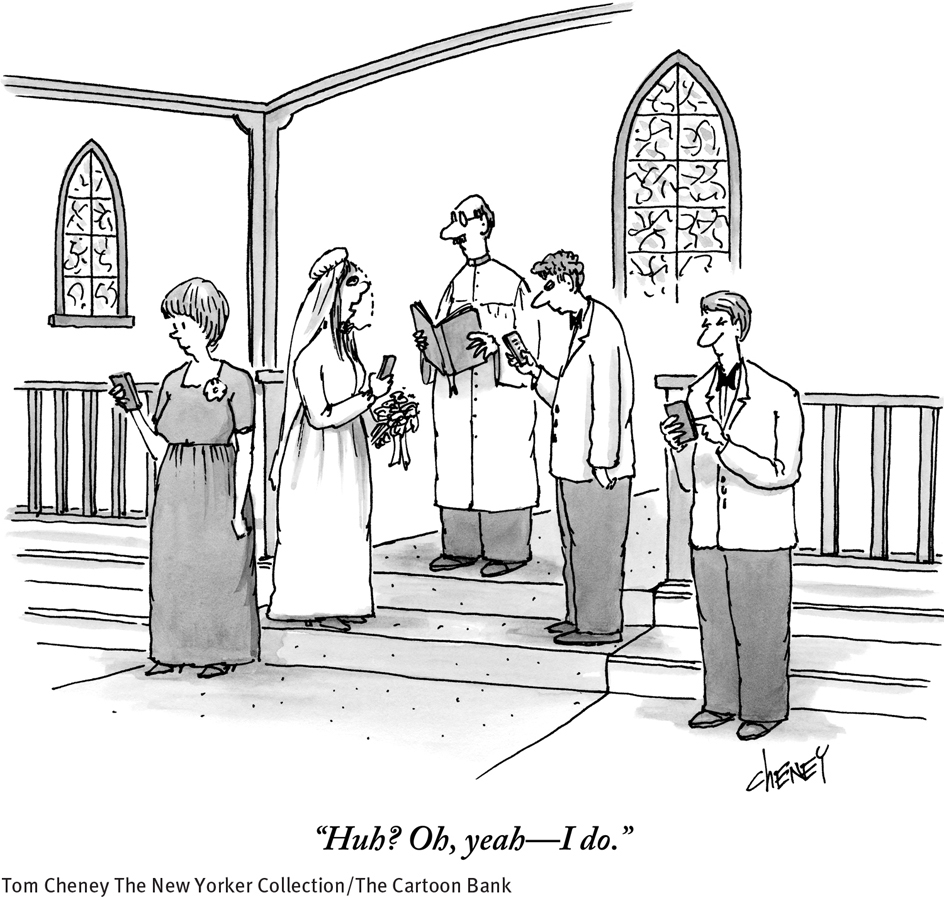

Texting has now become the leading way that most people communicate with others (Cocotas, 2013). The average 18-

Based on her studies, MIT professor Sherry Turkle (2013, 2012) has concluded that communicating primarily via text does indeed affect relationships negatively. Many of her participants reported, “I’d rather text than talk.” Turkle concludes from her research that people often use texting as a crutch to avoid direct communication and possible confrontations. Moreover, her participants say that they prefer texting over face-

In related work, researcher Karla Klein Murdock (2013) has investigated the social, emotional, mental, and physical tolls of extreme texting. In one study, Murdock interviewed 83 college freshmen about their daily texting habits, along with their levels of social and personal stress, sleep patterns, and happiness (Murdock, 2013). Murdock found that hastily written texts (which is to say, most texts) often lend themselves to misunderstandings between senders and receivers—

Can you think of ways in which texting might sometimes be helpful to relationships and communications?

None of this suggests that texting per se is a detriment to social or personal happiness. Rather, it seems to be the exclusive and excessive use of it that is the problem. It just may be that important discussions are better served by in-![]()

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened.”

Dr. Seuss

Cognitive ViewsCognitive theorists believe that people with unipolar depression persistently view events in negative ways and that such perceptions lead to their disorder. The two most influential cognitive explanations are the theory of negative thinking and the theory of learned helplessness.

NEGATIVE THINKINGAaron Beck believes that negative thinking, rather than underlying conflicts or a reduction in positive rewards, lies at the heart of depression (Beck & Weishaar, 2014; Beck, 2002, 1991, 1967). Other cognitive theorists—

Beck believes that some people develop maladaptive attitudes as children, such as “My general worth is tied to every task I perform” or “If I fail, others will feel repelled by me.” The attitudes result from their own experiences, their family relationships, and the judgments of the people around them (see Figure 7-2 below). Many failures are inevitable in a full, active life, so such attitudes are inaccurate and set the stage for all kinds of negative thoughts and reactions. Beck suggests that later in these people’s lives, upsetting situations may trigger an extended round of negative thinking. That thinking typically takes three forms, which he calls the cognitive triad: the individuals repeatedly interpret (1) their experiences, (2) themselves, and (3) their futures in negative ways that lead them to feel depressed. The cognitive triad is at work in the thinking of this depressed person:

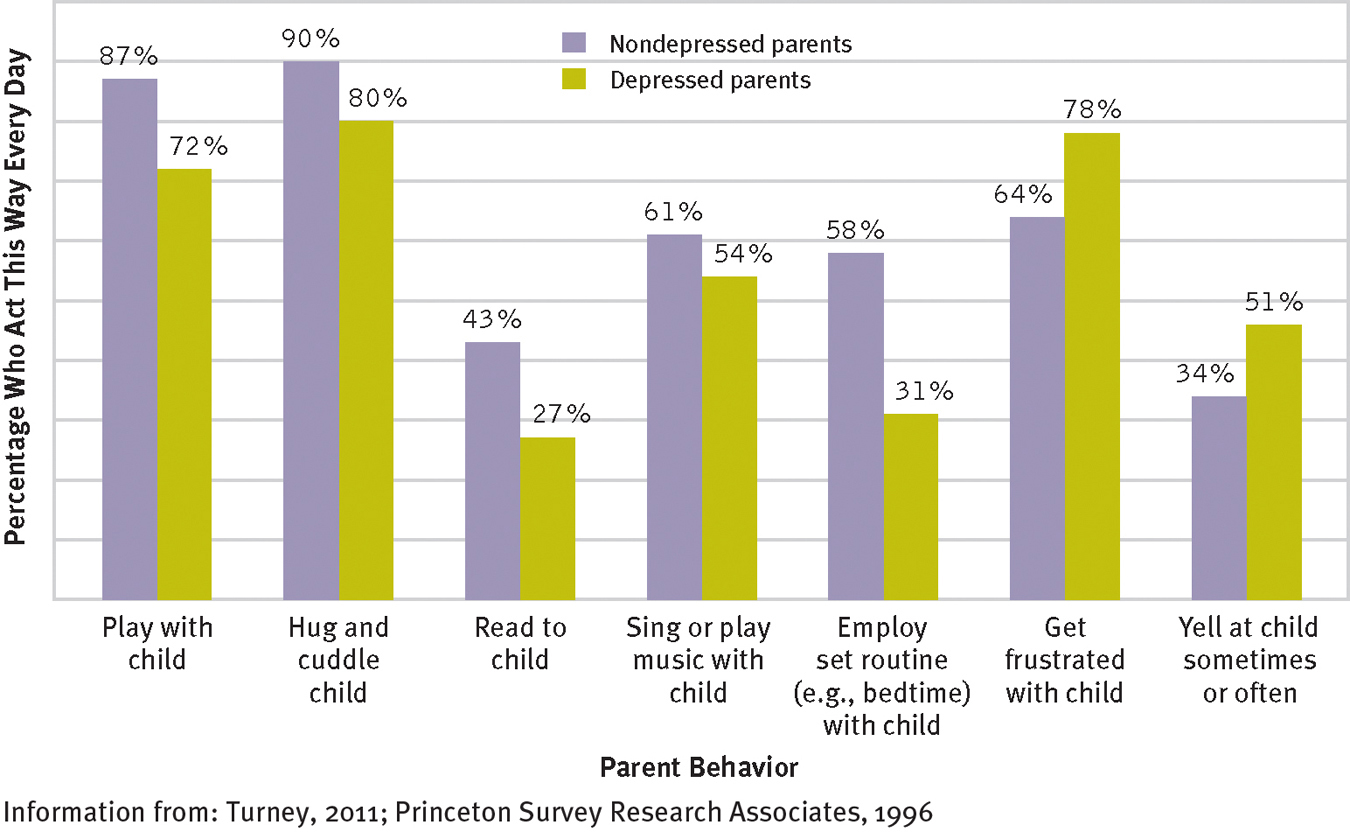

How depressed parents and their children interact

Depressed parents are less likely than nondepressed parents to play with, hug, read to, or sing to their young children each day or to employ the same routine each day. They are also more likely to get frustrated with their children on a daily basis. Such problematic interactions may help explain the repeated research finding that children of depressed parents are more likely than other children to have emotional, cognitive, or behavioral difficulties (Information from: Turney, 2011; Princeton Survey Research Associates, 1996).

cognitive triad The three forms of negative thinking that Aaron Beck theorizes lead people to feel depressed. The triad consists of a negative view of one’s experiences, oneself, and the future.

cognitive triad The three forms of negative thinking that Aaron Beck theorizes lead people to feel depressed. The triad consists of a negative view of one’s experiences, oneself, and the future.

One-

I can’t bear it. I can’t stand the humiliating fact that I’m the only woman in the world who can’t take care of her family, take her place as a real wife and mother, and be respected in her community. When I speak to my young son Billy, I know I can’t let him down, but I feel so ill-

(Fieve, 1975)

According to Beck, depressed people also make errors in their thinking. In one common error of logic, they draw arbitrary inferences—

Finally, depressed people have automatic thoughts, a steady train of unpleasant thoughts that keep suggesting to them that they are inadequate and that their situation is hopeless. Beck labels these thoughts “automatic” because they seem to just happen, as if by reflex. In the course of only a few hours, depressed people may be visited by hundreds of such thoughts: “I’m worthless. … I’ll never amount to anything … I let everyone down. … Everyone hates me. … My responsibilitiesare overwhelming. … I’ve failed as a parent … I’m stupid. … Everything is difficult for me. … Things will never change.” One therapist said of a depressed client, “By the end of the day, she is worn out, she has lived a thousand painful accidents, participated in a thousand deaths, mourned a thousand mistakes” (Mendels, 1970).

automatic thoughts Numerous unpleasant thoughts that help to cause or maintain depression, anxiety, or other forms of psychological dysfunction.

automatic thoughts Numerous unpleasant thoughts that help to cause or maintain depression, anxiety, or other forms of psychological dysfunction.

Many studies have produced evidence in support of Beck’s explanation (Pössel & Black, 2014; Rehm, 2010). Several of them confirm that depressed people hold maladaptive attitudes and that the more of these maladaptive attitudes they hold, the more depressed they tend to be (Thomas & Altareb, 2012; Evans et al., 2005). Still other research has found the cognitive triad at work in depressed people (Lai et al., 2014; Benas & Gibb, 2011). In various studies, depressed people seem to recall unpleasant experiences more readily than positive ones, rate their performances on laboratory tasks lower than nondepressed people do, and select pessimistic statements in storytelling tests (for example, “I expect my plans will fail”).

Beck’s claims about errors in logic have also received research support (Alcalar et al., 2012). In one study, female participants—

Finally, research has supported Beck’s claim that automatic thoughts are tied to depression (Alcalar et al., 2012). In several classic studies, nondepressed participants who are tricked into reading negative automatic-

This body of research shows that negative thinking is indeed linked to depression, but it fails to show that such patterns of thought are the cause and core of unipolar depression. It could be that a central mood problem leads to thinking difficulties that then take a further toll on mood, behavior, and physiology.

LEARNED HELPLESSNESSFeelings of helplessness fill this account of a young woman’s depression:

Mary was 25 years old and had just begun her senior year in college. … Asked to recount how her life had been going recently, Mary began to weep. Sobbing, she said that for the last year or so she felt she was losing control of her life and that recent stresses (starting school again, friction with her boyfriend) had left her feeling worthless and frightened. Because of a gradual deterioration in her vision, she was now forced to wear glasses all day. “The glasses make me look terrible,” she said, and “I don’t look people in the eye much any more.” Also, to her dismay, Mary had gained 20 pounds in the past year. She viewed herself as overweight and unattractive. At times she was convinced that with enough money to buy contact lenses and enough time to exercise she could cast off her depression; at other times she believed nothing would help. … Mary saw her life deteriorating in other spheres, as well. She felt overwhelmed by schoolwork and, for the first time in her life, was on academic probation. … In addition to her dissatisfaction with her appearance and her fears about her academic future, Mary complained of a lack of friends. Her social network consisted solely of her boyfriend, with whom she was living. Although there were times she experienced this relationship as almost unbearably frustrating, she felt helpless to change it and was pessimistic about its permanence.

(Spitzer et al., 1983, pp. 122-

Mary feels that she is “losing control of her life.” According to psychologist Martin Seligman (1975), such feelings of helplessness are at the center of her depression. Since the mid-

learned helplessness The perception, based on past experiences, that one has no control over one’s reinforcements.

learned helplessness The perception, based on past experiences, that one has no control over one’s reinforcements.

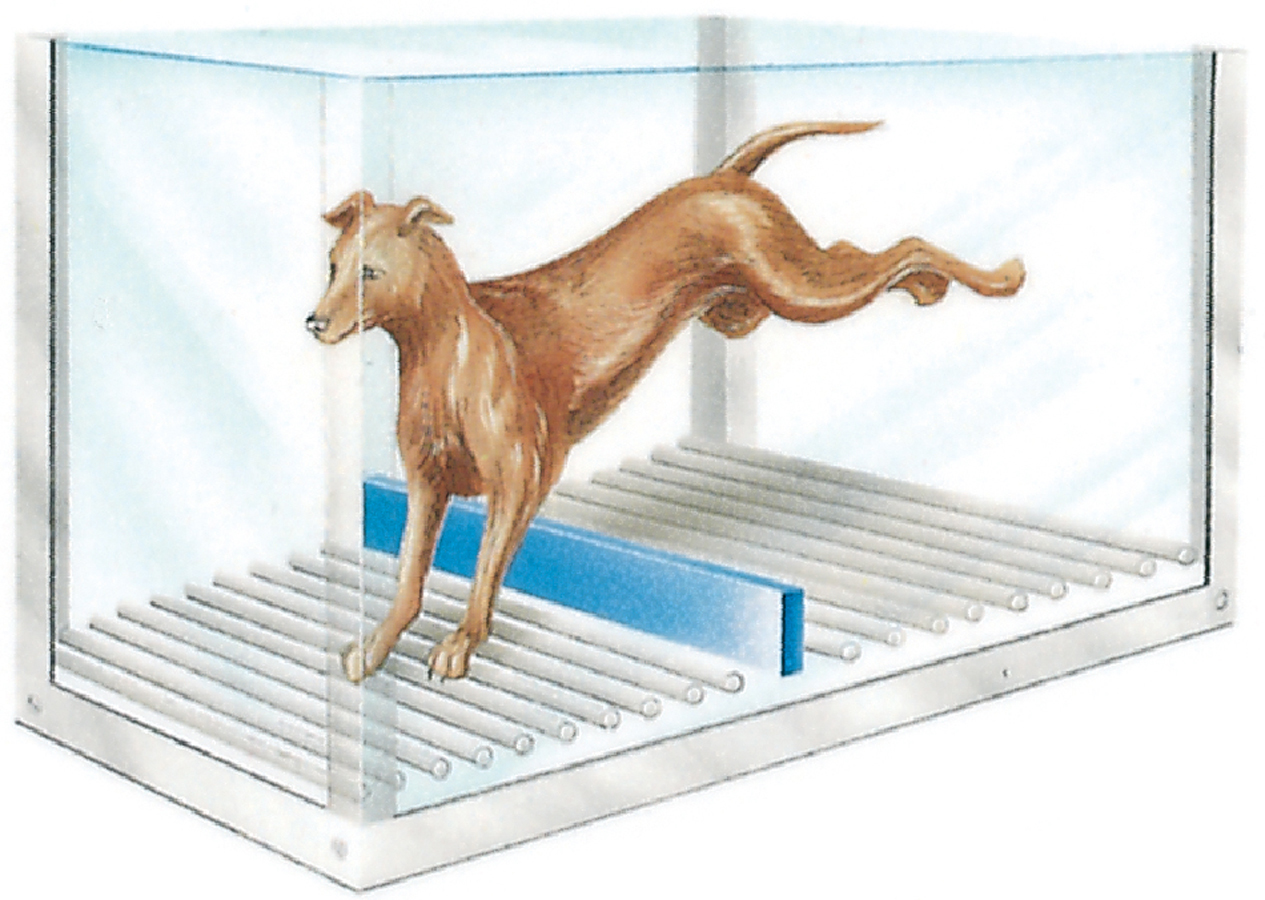

Seligman’s theory first began to take shape when he was working with laboratory dogs. In one procedure, he strapped dogs into an apparatus called a hammock, in which they received shocks periodically no matter what they did. The next day each dog was placed in a shuttle box, a box divided in half by a barrier over which the animal could jump to reach the other side (see Figure 7-3). Seligman applied shocks to the dogs in the box, expecting that they, like other dogs in this situation, would soon learn to escape by jumping over the barrier. However, most of these dogs failed to learn anything in the shuttle box. After a flurry of activity, they simply “lay down and quietly whined” and accepted the shock.

Jumping to safety

Experimental animals learn to escape or avoid shocks that are administered on one side of a shuttle box by jumping to the other (safe) side.

Seligman decided that while receiving inescapable shocks in the hammock the day before, the dogs had learned that they had no control over unpleasant events (shocks) in their lives. That is, they had learned that they were helpless to do anything to change negative situations. Thus, when later they were placed in a new situation (the shuttle box) where they could in fact control their fate, they continued to believe that they were generally helpless. Seligman noted that the effects of learned helplessness greatly resemble the symptoms of human depression, and he proposed that people in fact become depressed after developing a general belief that they have no control over reinforcements in their lives.

In numerous human and animal studies, participants who undergo helplessness training have displayed reactions similar to depressive symptoms (Dygdon & Dienes, 2013; Vollmayr & Gass, 2013). When, for example, human participants are exposed to uncontrollable negative events, they later score higher than other individuals on a depressive mood scale (Miller & Seligman, 1975). Similarly, helplessness-

The learned helplessness explanation of depression has been revised somewhat over the past two decades. According to a new version of the theory, the attribution-

|

Event: “I failed my psych test today.” |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

INTERNAL |

EXTERNAL |

||

|

|

Stable |

Unstable |

Stable |

Unstable |

|

Global |

“I have a problem with test anxiety.” |

“Getting into an argument with my roommate threw my whole day off.” |

“Written tests are an unfair way to assess knowledge.” |

“No one does well on tests that are given the day after vacation.” |

|

Specific |

“I just have no grasp of psychology.” |

“I got upset and froze when I couldn’t answer the first two questions.” |

“Everyone knows that this professor enjoys giving unfair tests.” |

“This professor didn’t put much thought into the test because of the pressure of her book deadline.” |

Consider a college student whose girlfriend breaks up with him. If he attributes this loss of control to an internal cause that is both global and stable—

Hundreds of studies have supported the relationship between styles of attribution, helplessness, and depression (Rotenberg et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2010). In one, depressed persons were asked to fill out an Attributional Style Questionnaire both before and after successful therapy. Before therapy, their depression was accompanied by the internal/global/stable pattern of attribution. At the end of therapy and again one year later, their depression had improved and their interpretive styles were less likely to be limited to internal, global, and stable attributions (Seligman et al., 1988).

Some theorists have refined the helplessness model yet again in recent years. They suggest that attributions are likely to cause depression only when they further produce a sense of hopelessness in a person (Wain et al., 2011; Abramson et al., 2002, 1989). By taking this factor into consideration, clinicians are often able to predict depression with still greater precision (Wang et al., 2013).

Although the learned helplessness theory of unipolar depression has been very influential, it too has imperfections. First, laboratory helplessness does not parallel depression in every respect. Uncontrollable shocks in the laboratory, for example, almost always produce anxiety along with the helplessness effects (Seligman, 1975); in contrast, human depression is often, but not always, accompanied by anxiety (Shorter, 2013). Second, much of the learned helplessness research relies on animal subjects. It is impossible to know whether the animals’ symptoms do in fact reflect the clinical depression found in humans. Third, the attributional feature of the theory raises difficult questions. What about the dogs and rats who learn helplessness? Can animals make attributions, even implicitly?

Sociocultural Views

Sociocultural theorists propose that unipolar depression is strongly influenced by the social context that surrounds people. Their belief is supported by the finding, discussed earlier, that depression is often triggered by outside stressors. Once again, there are two kinds of sociocultural views—

The Family-

The connection between declining social rewards and depression is a two-

Consistent with these findings, depression has been tied repeatedly to the unavailability of social support such as that found in a happy marriage (Ito & Sagara, 2014; Kendler et al., 2005). People who are separated or divorced display at least three times the depression rate of married or widowed people and double the rate of those who have never been married (Schultz, 2007; Weissman et al., 1991). In some cases, the spouse’s depression may contribute to marital discord, a separation, or divorce, but often the interpersonal conflicts and low social support found in troubled relationships seem to lead to depression (Najman et al., 2014; Whisman, 2001).

Why might problems in the social arena—

Generally, there is a high correlation between level of marital conflict and degree of sadness: .37 for men and .42 for women (Whisman & Schonbrun, 2010; Whisman, 2001). Among those who are clinically depressed, the correlation rises to .66. In one study, researchers first assessed how satisfying the marital relationships of research participants were. They then discovered that over the next 12 months, participants who were in an unsatisfying relationship were three times more likely to have a major depressive episode than those in a satisfying relationship (Whisman & Bruce, 1999). Such findings led the experimenters to estimate that one-

Finally, it appears that people whose lives are isolated and without intimacy are particularly likely to become depressed at times of stress (Hölzel et al., 2011; Nezlek et al., 2000). Some highly publicized studies conducted in England several decades ago showed that women who had three or more young children, lacked a close confidante, and had no outside employment were more likely than other women to become depressed after going through stressful events (Brown, 2002; Brown & Harris, 1978). Studies have also found that depressed people who lack social support remain depressed longer than those who have a supportive spouse or warm friendships.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Loss of Confidants

Intimate social contact has been declining over the past 30 years. When research participants were asked in 1985 how many confidants they turned to for discussion of important matters, most answered 3. Today, the most common response to the same question is 2 (Bryner, 2011 McPherson, Smith-

The Multicultural PerspectiveTwo kinds of relationships have captured the interest of multicultural theorists: (1) links between gender and depression, and (2) ties between cultural and ethnic background and depression. In the case of gender, a strong relationship has been found, but a clear explanation for that relationship has yet to emerge. The clinical field is still sorting out whether and what ties exist between cultural factors and depression.

GENDER AND DEPRESSIONAs you have read, there is a strong link between gender and depression. Women in places as disparate as France, Sweden, Lebanon, New Zealand, and the United States are at least twice as likely as men to receive a diagnosis of unipolar depression (Schuch et al., 2014; McSweeney, 2004). Women also appear to be younger when depression strikes, to have more frequent and longer-

The artifact theory holds that women and men are equally prone to depression but that clinicians often fail to detect depression in men (Emmons, 2010; Brommelhoff et al., 2004). Perhaps men find it less socially acceptable to admit feeling depressed or to seek treatment. Perhaps depressed women display more emotional symptoms, such as sadness and crying, which are easily diagnosed, while depressed men mask their depression behind traditionally “masculine” symptoms such as anger. Although a popular explanation, this view has failed to receive consistent research support. It turns out that women are actually no more willing or able than men to identify their depressive symptoms and to seek treatment (McSweeney, 2004; Nolen-

The hormone explanation holds that hormone changes trigger depression in many women (Kurita et al., 2013; Parker & Brotchie, 2004). A woman’s biological life from her early teens to middle age is marked by frequent changes in hormone levels. Gender differences in rates of depression also span these same years. Research suggests, however, that hormone changes alone are not responsible for the high levels of depression in women (Whiffen & Demidenko, 2006; Kessler et al., 2003). Important social and life events that occur at puberty, pregnancy, and menopause could likewise have an effect. Hormone explanations have also been criticized as sexist, since they imply that a woman’s normal biology is flawed (see PsychWatch below).

The life stress theory suggests that women in our society are subject to more stress than men (Astbury, 2010; Keyes & Goodman, 2006). On average they face more poverty, more menial jobs, less adequate housing, and more discrimination than men—

The body dissatisfaction explanation states that females in Western society are taught, almost from birth, to seek a low body weight and slender body shape—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Paternal Postpartum Depression

Considerable research has already indicated that a mother’s postpartum depression can lead to disturbances in a child’s social, behavioral, and cognitive development. Research suggests that a father’s postpartum depression can have similar effects (Koh et al., 2014; Edoka et al., 2011).

The lack-

A final explanation for the gender differences found in depression is the rumination theory. As you read earlier, rumination is the tendency to keep focusing on one’s feelings when depressed and to consider repeatedly the causes and consequences of that depression (“Why am I so down? … I won’t be able to finish my work if I keep going like this. …”). Research shows that people who ruminate whenever they feel sad are more likely to become depressed and to stay depressed longer. It turns out that women are more likely than men to ruminate when their mood darkens, perhaps making them more vulnerable to the onset of clinical depression (Johnson & Whisman, 2013; Nolen-

Each of these explanations for the gender difference in unipolar depression offers food for thought. Each has gathered just enough supporting evidence to make it interesting and just enough evidence to the contrary to raise questions about its usefulness. Thus, at present, the gender difference in depression remains one of the most talked-

PsychWatch

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Déja Vu All Over Again

Back in the early 1990s, one of the biggest controversies in the development of DSM-

This recommendation set off an uproar. Many clinicians (including some dissenting members of the work group), several national organizations, interest groups, and the media warned that this diagnostic category would “pathologize” severe cases of premenstrual syndrome, or PMS, the premenstrual discomforts that are common and normal, and might cause women’s behavior in general to be attributed largely to “raging hormones” (a stereotype that society was finally rejecting). They argued that data were lacking to include the new category (Chase, 1993; DeAngelis, 1993).

The solution? A compromise. PMDD was not listed as a formal category in DSM-

CULTURAL BACKGROUND AND DEPRESSIONDepression is a worldwide phenomenon, and certain symptoms of this disorder seem to be constant across all countries. A landmark study of four countries—

How would you explain the relatively low rate of depression found among immigrants in the United States? Why do their depression rates eventually rise?

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Downside of Immigration

In the United States, new immigrants from all cultures and races display a lower rate of depression than do U.S. natives.

The rate of depression is equally high for adult natives and for adult immigrants who came to the United States by the age of 12.

(González et al., 2010; Breslau et al., 2007)

Within the United States, researchers have found few differences in the symptoms of depression among members of different ethnic or racial groups. Nor have they found significant differences in the overall rates of depression between such minority groups. On the other hand, recent research has revealed that there are often striking differences between ethnic/racial groups in the chronicity of depression. Chronicity refers to how likely it is that a person will have recurrent episodes of a disorder. Hispanic Americans and African Americans are 50 percent more likely than white Americans to have recurrent episodes of depression (González et al., 2010).

How might this difference in chronicity be explained? Data on the treatment of depression may provide a clue. As you will read in the next chapter, 54 percent of depressed white Americans receive treatment for their disorders (medication and/or psychotherapy), compared with 34 percent of depressed Hispanic Americans and 40 percent of depressed African Americans (González et al., 2010). It may be that minority groups in the United States are more vulnerable to repeated experiences of depression partly because many of their members have more limited treatment opportunities when they are depressed.

A close look at research findings also reveals that although the overall rates of depression are similar among minority groups, specific ethnic populations living under unusually oppressive circumstances sometimes do have strikingly high rates of depression (Kim et al., 2014; Matsumoto & Juang, 2008; Ayalon & Young, 2003). A study of one American Indian community in the United States, for example, showed that the lifetime risk of developing depression was 37 percent among women, 19 percent among men, and 28 percent overall, much higher than the risk in the general U.S. population (Kinzie et al., 1992). High prevalence rates of this kind may be linked to the terrible social and economic pressures faced by the people who live on American Indian reservations. Similarly, in one survey of Hispanic and African Americans residing in public housing, almost half of the respondents reported that they were suffering from depression (Bazargan et al., 2005). Within these minority populations, the likelihood of being depressed rose along with the individual’s degree of poverty, family size, and number of health problems.

Finally, research has revealed that depression is distributed unevenly within some minority groups. This is not totally surprising, given that each minority group itself is comprised of individuals of varied backgrounds and cultural values. For example, depression is more common among Hispanic and African Americans born in the United States than among Hispanic and African American immigrants (González et al., 2010; Matsumoto & Juang, 2008). Moreover, within the Hispanic American population, Puerto Ricans have a higher rate of depression than do Mexican Americans or Cuban Americans, whereas among African Americans, those whose families originally came to the United States from Africa and those whose families came by way of the Caribbean Islands have similar rates of depression (González et al., 2010; Miranda et al., 2005).