9.2 What Triggers a Suicide?

Suicidal acts may be connected to recent events or current conditions in a person’s life. Although such factors may not be the basic motivation for the suicide, they can precipitate it. Common triggering factors include stressful events, mood and thought changes, alcohol and other drug use, mental disorders, and modeling.

Stressful Events and Situations

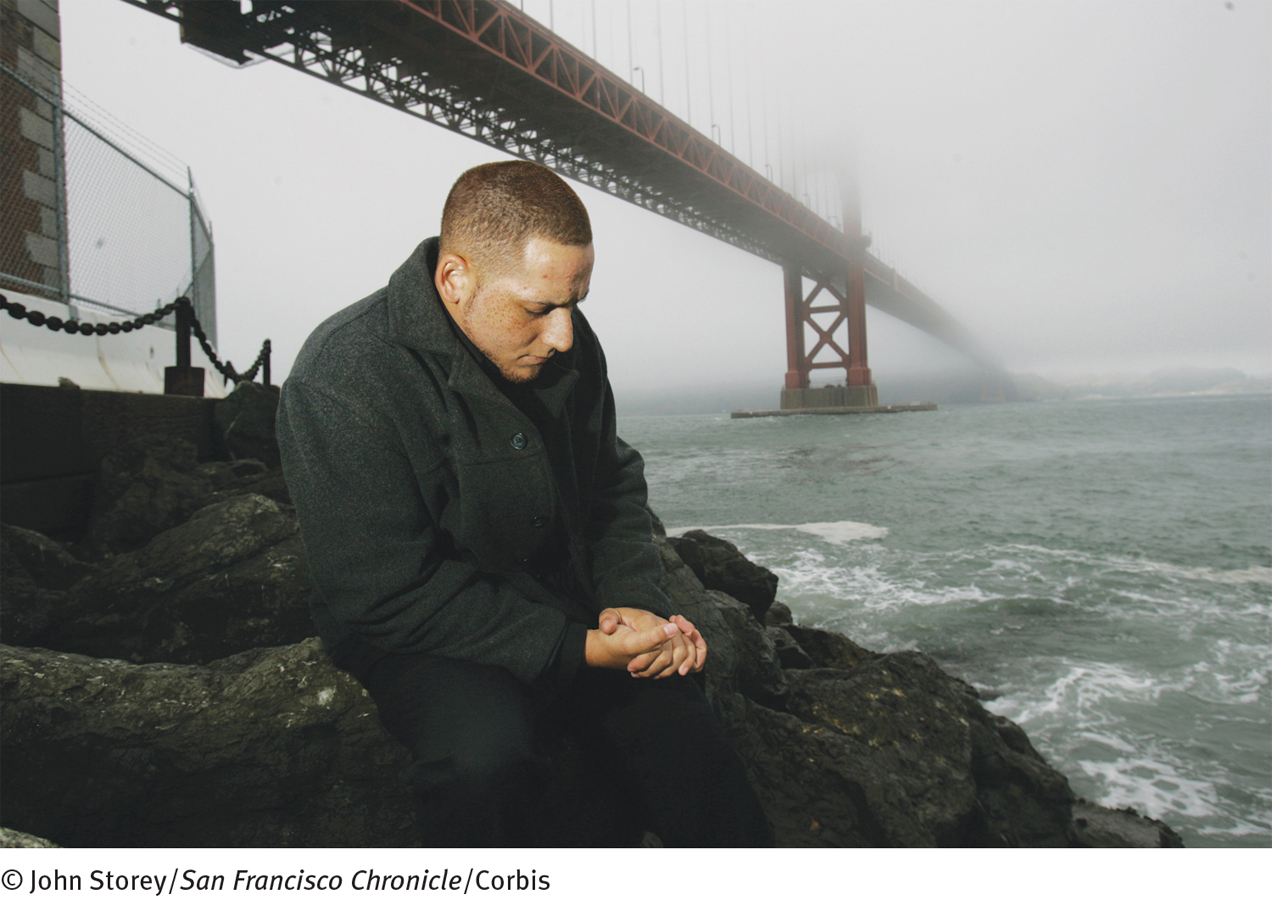

Researchers have counted more stressful events in the recent lives of suicide attempters than in the lives of nonattempters (Foster, 2011; Pompili et al., 2011). One stressor that has been consistently linked to suicide is combat stress. Research indicates that combat veterans from various wars are more than twice as likely to commit suicide as nonveterans (Jakupcak & Varra, 2011). At the beginning of this chapter, for example, you read about a young man who committed suicide upon returning to civilian life, after experiencing the enormous stressors of combat in Iraq.

The stressors that help lead to suicide do not need to be as horrific as those tied to combat. Common forms of immediate stress seen in cases of suicide are the loss of a loved one through death, divorce, or rejection (Roskar et al., 2011); loss of a job (Milner el al., 2014; Kuroki, 2010); significant financial loss (Houle & Light, 2014); and stress caused by hurricanes or other natural disasters, even among very young children. A suicide attempt may also be precipitated by a series of recent events that have a combined impact, rather than by a single event, as in the following case:

Sally’s suicide attempt took place in the context of a very difficult year for the family. Sally’s mother and stepfather separated after 9 years of marriage. After the father moved out, he visited the family erratically. Four months after he moved out of the house, the mother’s boyfriend moved into the house. The mother planned to divorce her husband and marry her boyfriend, who had become the major disciplinarian for the children, a fact that Sally intensely resented. Sally also complained of being “left out” in relation to the closeness she had with her mother. Another problem for Sally had been two school changes in the last 2 years which left Sally feeling friendless. In addition, she failed all her subjects in the last marking period.

(Pfeffer, 1986, pp. 129–

People may also attempt suicide in response to long-

Social IsolationAs you saw in the cases of Dave, Demaine, and Tya, people from loving families or supportive social systems may commit suicide. However, those without such social supports are particularly vulnerable to suicidal thinking and actions. Researchers have found a heightened risk for suicidal behavior among those who feel little sense of “belongingness,” believe that they have limited or no social support, live alone, and have ongoing conflicts with other people (You et al., 2011).

Serious IllnessPeople whose illnesses cause them great pain or severe disability may try to commit suicide, believing that death is unavoidable and imminent (Schneider & Shenassa, 2008). They may also believe that the suffering and problems caused by their illnesses are more than they can endure. Studies suggest that as many as one-

Abusive or Repressive EnvironmentVictims of an abusive or repressive environment from which they have little or no hope of escape sometimes commit suicide. For example, some prisoners of war, inmates of concentration camps, abused spouses, abused children, and prison inmates try to end their lives (Fazel et al., 2011). Like those who have serious illnesses, these people may feel that they can endure no more suffering and believe that there is no hope for improvement in their condition.

Occupational StressSome jobs create feelings of tension or dissatisfaction that may trigger suicide attempts. Research has found particularly high suicide rates among psychiatrists and psychologists, physicians, nurses, dentists, lawyers, police officers, farmers, and unskilled laborers (Kleespies et al., 2011; Skegg et al., 2010). Such correlations do not necessarily mean that occupational pressures directly cause suicidal actions. Perhaps unskilled workers are responding to financial insecurity rather than job stress when they attempt suicide. Similarly, rather than reacting to the emotional strain of their work, suicidal psychiatrists and psychologists may have long-

Mood and Thought Changes

Many suicide attempts are preceded by a change in mood (see PsychWatch below). The change may not be severe enough to warrant a diagnosis of a mental disorder, but it does represent a significant shift from the person’s past mood. The most common change is an increase in sadness. Also common are increases in feelings of anxiety, tension, frustration, anger, or shame (Reisch et al., 2010). In fact, Shneidman (2005, 2001) believed that the key to suicide is “psychache,” a feeling of psychological pain that seems intolerable to the person. A study of 88 patients found that those who scored higher on a measure called the Psychological Pain Assessment Scale were indeed more likely than others to commit suicide (Pompili et al., 2008).

Suicide attempts may also be preceded by shifts in patterns of thinking. People may become preoccupied with their problems, lose perspective, and see suicide as the only effective solution to their difficulties (Shneidman, 2005, 2001). They often develop a sense of hopelessness—a pessimistic belief that their present circumstances, problems, or mood will not change. In fact, one study found that people who generally expressed feelings of hopelessness were 11 times more likely to commit suicide over a 13-

hopelessness A pessimistic belief that one’s present circumstances, problems, or mood will not change.

hopelessness A pessimistic belief that one’s present circumstances, problems, or mood will not change.

PsychWatch

Can Music Inspire Suicide?

In 2008, a 13-

This tragedy is hardly the first time that music has been blamed by the public for suicidal acts. In fact, over the years, music genres as varied as country, opera, heavy metal, and pop rock have been pointed to as negative influences, particularly on teenagers, that can lead to suicide attempts (Copley, 2008; Snipes & Maguire, 1995; Litman & Farberow, 1994; Stack et al., 1994; Wass et al, 1991). Little research has been conducted on this issue, and that which has been done fails to provide clear support for such claims. But the concerns go on and, indeed, have helped lead to the current music rating system, which informs consumers (and their parents) about the kinds of language and themes that are on the CDs or music downloads.

Two famous cases in the 1980s first brought this concern into public awareness. One involved the music of Ozzy Osbourne, leader of the band Black Sabbath. In the early days of Black Sabbath, Osbourne and the band centered much of their music on psychological themes, and the band’s music was even perceived by many as having a “satanic” bent.

Osbourne departed the band for a solo career in 1979 that lasted into the late 1990s. During this period, his solo music was blamed for three suicides. In 1984, a 19-

A second famous case involved the music of the heavy metal band Judas Priest. In 1985, two boys died after shooting themselves in the head with a shotgun. The boys had been drunk and on drugs and shot themselves in a “suicide pact” after listening to a Judas Priest album for hours. Lawyers for the boys’ families claimed that Judas Priest’s 1977 song “Better by You, Better Than Me” contained, when played backward, the subliminal message “Do it” as well as “Try suicide” and “Let’s be dead.” The band’s lawyers countered that any song played backward might seem to have a hidden message. The trial judge agreed, and he dismissed the $6.2 million lawsuit in 1990. He ruled that even if the lyrics conveyed subliminal messages, such messages had been unintentional.

If the music in these cases did not itself lead to suicide, what did? A number of clinicians have argued that the people in these cases were probably suffering from several kinds of factors typically linked to suicide—

Of course, the dismissal of these suits did not put to rest the concerns of parents, which grow even stronger whenever parents read about a teenager—

Many people who attempt suicide fall victim to dichotomous thinking, viewing problems and solutions in rigid either/or terms (Shneidman, 2005, 2001, 1993). Indeed, Shneidman said that the “four-

dichotomous thinking Viewing problems and solutions in rigid either/or terms.

dichotomous thinking Viewing problems and solutions in rigid either/or terms.

I was so desperate. I felt, my God, I couldn’t face this thing. Everything was like a terrible whirlpool of confusion. And I thought to myself: There’s only one thing to do. I just have to lose consciousness. That’s the only way to get away from it. The only way to lose consciousness, I thought, was to jump off something good and high….

(Shneidman, 1987, p. 56)

Alcohol and Other Drug Use

Studies indicate that as many as 70 percent of the people who attempt suicide drink alcohol just before they do so (Crosby et al., 2009; McCloud et al., 2004). Autopsies reveal that about one-

Mental Disorders

Although people who attempt suicide may be troubled or anxious, they do not necessarily have a psychological disorder. Nevertheless, the majority of all suicide attempters do have such a disorder (Singhal et al., 2014; Nock et al., 2013; Fountoulakis & Rihmer, 2011). Research suggests that as many as 70 percent of all suicide attempters had been experiencing severe depression, 20 percent chronic alcoholism, and 10 percent schizophrenia (see Table 9-2). Correspondingly, as many as 25 percent of people with each of these disorders try to kill themselves. People who are both depressed and dependent on alcohol seem particularly prone to suicidal impulses (Nenadić-Šviglin et al., 2011). Certain anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder and panic disorder, have also been linked to suicide (Rappaport et al., 2014), but in most cases of suicide these disorders occur in conjunction with major depressive disorder, a substance-

|

1. |

Depressive disorder and certain other mental disorders |

|

2. |

Alcoholism and other forms of substance abuse |

|

3. |

Suicidal ideation, talk, preparation; certain religious ideas |

|

4. |

Prior suicide attempts |

|

5. |

Lethal methods |

|

6. |

Social withdrawal, isolation, living alone, loss of support |

|

7. |

Hopelessness, feeling trapped, cognitive rigidity |

|

8. |

Impulsivity and risk- |

|

9. |

Being an older white American male |

|

10. |

Modeling, suicide in the family, genetics |

|

11. |

Economic or work problems; certain occupations |

|

12. |

Marital problems, family pathology |

|

13. |

Dramatic changes in mood |

|

14. |

Anxiety |

|

15. |

Stress and stressful events |

|

16. |

Anger, aggression, irritability |

|

17. |

Psychosis |

|

18. |

Physical illness |

|

19. |

Sleep problems |

|

Information from: Crump et al 2014; Ferrari et al., 2014; Rudd et al., 2006; Papolos et al., 2005. |

|

As you saw in Chapter 7, people with major depressive disorder often have suicidal thoughts. One program in Sweden was able to reduce the community suicide rate by teaching physicians how to recognize and treat depression at an early stage (Rihmer, Rutz, & Pihlgren, 1995). Similarly, a recent review in the United States found that treatments for depression consistently reduce the rate of suicidal thinking, attempts, and completions among patients (Sakinofsky, 2011). Even when depressed people are showing improvements in mood, however, they may remain at high risk for suicide. In fact, among those who are severely depressed, the risk of suicide may actually increase as their mood improves and they have more energy to act on their suicidal wishes. Recall, for example, Jonathan Boucher, the combat veteran whose case opened this chapter. Just before he committed suicide, he had seemed to be calm and enjoying life again, according to family members and friends.

Severe depression also may play a key role in suicide attempts made by those with serious physical illnesses (Werth, 2004). A study of 44 patients with terminal illnesses revealed that fewer than one-

A number of the people who drink alcohol or use drugs just before a suicide attempt actually have a long history of abusing such substances (Ries, 2010). The basis for the link between substance-

People with schizophrenia, as you will see in Chapter 14, may hear voices that are not actually present (hallucinations) or hold beliefs that are clearly false and perhaps bizarre (delusions). The popular notion is that when such people kill themselves, they must be responding to an imagined voice commanding them to do so or to a delusion that suicide is a grand and noble gesture. Research indicates, however, that suicides by people with schizophrenia more often reflect feelings of demoralization or fears of further mental deterioration (Meltzer, 2011; Pompili & Lester, 2007). Many young and unemployed people with schizophrenia who have had relapses over several years come to believe that the disorder will forever disrupt their lives. Still others seem to be disheartened by their substandard living conditions. Suicide is the leading cause of premature death among people with schizophrenia.

Modeling: The Contagion of Suicide

It is not unusual for people, particularly teenagers, to try to commit suicide after observing or reading about someone else who has done so (Hagihara et al., 2014; Ali, Dwyer, & Rizzo, 2011). Perhaps they have been struggling with major problems and the other person’s suicide seems to reveal a possible solution, or perhaps they have been thinking about suicide and the other person’s suicide seems to give them permission or finally persuades them to act. Either way, one suicidal act apparently serves as a model for another. Suicides by family members and friends, those by celebrities, other highly publicized suicides, and those by coworkers or colleagues are particularly common triggers.

Family Members and FriendsA recent suicide by a family member or friend increases the likelihood that a person will attempt suicide (Ali et al., 2011). Of course, the death of a family member or friend, especially when self-

CelebritiesResearch suggests that suicides by entertainers, political figures, and other well-

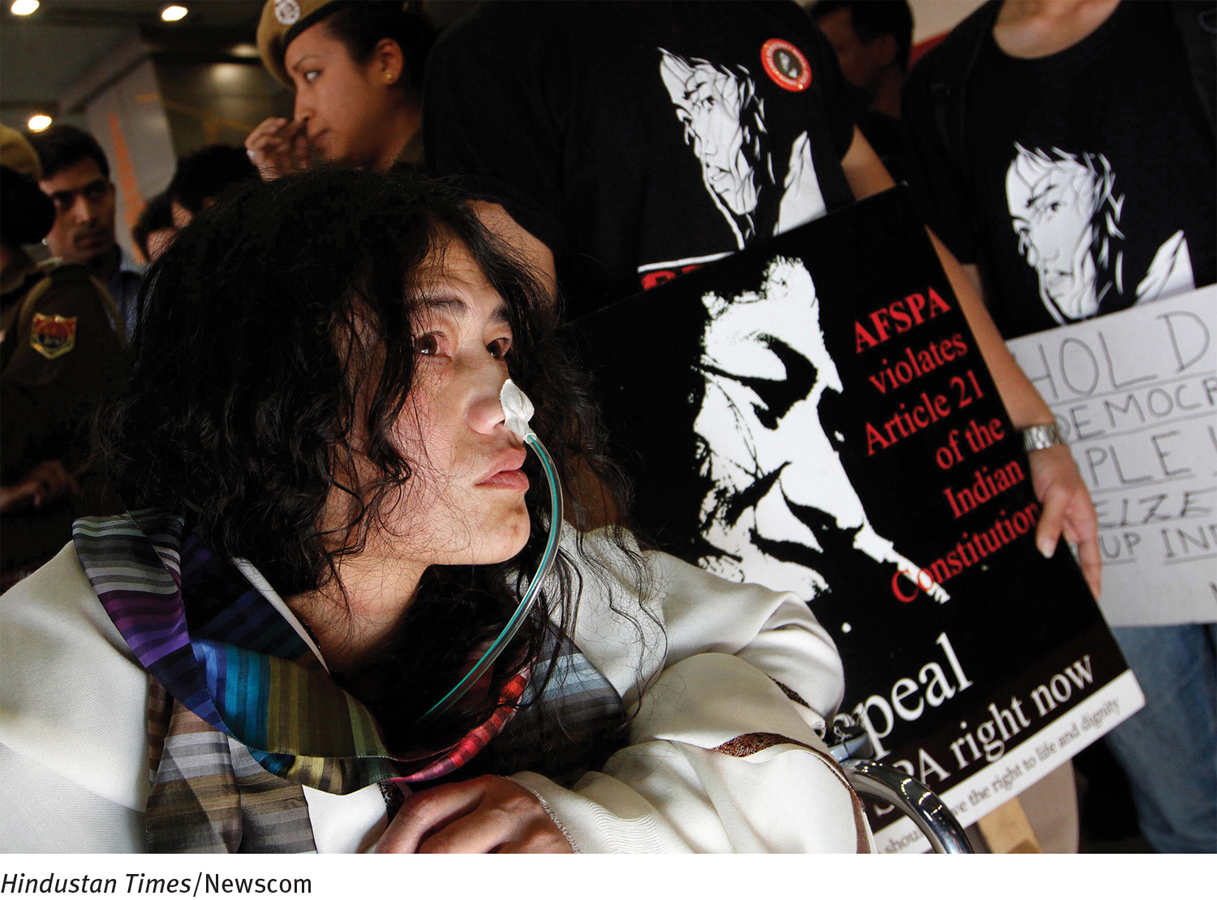

Other Highly Publicized CasesSuicides with bizarre or unusual aspects often receive intense coverage by the news media. Such highly publicized accounts may lead to similar suicides (Hagihara et al., 2014; Blood et al., 2007; Gould et al., 2007). During the year after a widely publicized, politically motivated suicide by self-

Even a media program that is clearly intended to educate and help viewers may have the paradoxical effect of spurring imitators. One study found a dramatic increase in the rate of suicide among West German teenagers after the airing of a television documentary showing the suicide of a teenager who jumped under a train (Schmidtke & Häfner, 1988). The number of railway suicides by male teenagers increased by 175 percent after the program was aired.

Some clinicians argue that more responsible reporting could reduce this frightening impact of highly publicized suicides (Mann & Currier, 2011; Blood et al., 2007). A careful approach to reporting was seen in the media’s coverage of the suicide of Kurt Cobain. MTV’s repeated theme on the evening of the suicide was “Don’t do it!” In fact, thousands of young people called MTV and other radio and television stations in the hours after Cobain’s death, upset, frightened, and in some cases suicidal. Some of the stations responded by posting the phone numbers of suicide prevention centers, presenting interviews with suicide experts, and offering counseling services and advice directly to callers. Perhaps because of such efforts, the usual rate of suicide both in Seattle, where Cobain lived, and elsewhere held steady during the weeks that followed (Colburn, 1996).

Coworkers and ColleaguesThe word-