3.2 Diagnosis: Does the Client’s Syndrome Match a Known Disorder?

Clinicians use the information from interviews, tests, and observations to construct an integrated picture of the factors that are causing and maintaining a client’s disturbance, a construction sometimes known as a clinical picture (Goldfinger & Pomerantz, 2014). Clinical pictures also may be influenced to a degree by the clinician’s theoretical orientation (Garb, 2010, 2006). The psychologist who worked with Franco held a cognitive-

Franco’s mother had reinforced his feelings of insecurity and his belief that he was unintelligent and inferior. When teachers tried to encourage and push Franco, his mother actually called him “an idiot.” Although he was the only one in his family to attend college and did well there, she told him he was too inadequate to succeed in the world. When he received a B in a college algebra course, his mother told him, “You’ll never have money.” She once told him, “You’re just like your father, dumb as a post,” and railed against “the dumb men I got stuck with.”

As a child Franco had watched his parents argue. Between his mother’s self-

He took the termination of his relationship with Maria as proof that he was “stupid.” He felt foolish to have broken up with her. He interpreted his behavior and the break-

BETWEEN THE LINES

What Is a Nervous Breakdown?

The term “nervous breakdown” is used by laypersons, not clinicians. Most people use it to refer to a sudden psychological disturbance that incapacitates a person, perhaps requiring hospitalization (Hall-

diagnosis A determination that a person’s problems reflect a particular disorder.

With the assessment data and clinical picture in hand, clinicians are ready to make a diagnosis—that is, a determination that a person’s psychological problems constitute a particular disorder. When clinicians decide, through diagnosis, that a client’s pattern of dysfunction reflects a particular disorder, they are saying that the pattern is basically the same as one that has been displayed by many other people, has been investigated in a variety of studies, and perhaps has responded to particular forms of treatment. They can then apply what is generally known about the disorder to the particular individual they are trying to help. They can, for example, better predict the future course of the person’s problem and the treatments that are likely to be helpful.

Classification Systems

Why do you think many clinicians prefer the label “person with schizophrenia” over “schizophrenic person”?

syndrome A cluster of symptoms that usually occur together.

classification system A list of disorders, along with descriptions of symptoms and guidelines for making appropriate diagnoses.

The principle behind diagnosis is straightforward. When certain symptoms occur together regularly—

In 1883, Emil Kraepelin developed the first modern classification system for abnormal behavior (see Chapter 1). His categories formed the foundation for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the classification system currently written by the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013). The DSM is the most widely used classification system in North America. Most other countries rely primarily on a system called the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), developed by the World Health Organization, which lists both medical and psychological disorders.

The content of the DSM has been changed significantly over time. The current edition, called DSM-

DSM-5

DSM-

DSM-

Categorical Information First, the clinician must decide whether the person is displaying one of the hundreds of psychological disorders listed in the manual. Some of the most frequently diagnosed disorders are the anxiety disorders and depressive disorders.

ANXIETY DISORDERS People with anxiety disorders may experience general feelings of anxiety and worry (generalized anxiety disorder); fears of specific situations, objects, or activities (phobias); anxiety about social situations (social anxiety disorder); repeated outbreaks of panic (panic disorder); or anxiety about being separated from one’s parents or other key individuals (separation anxiety disorder).

DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS People with depressive disorders may experience an episode of extreme sadness and related symptoms (major depressive disorder), persistent and chronic sadness (persistent depressive disorder), or severe premenstrual sadness and related symptoms (premenstrual dysphoric disorder).

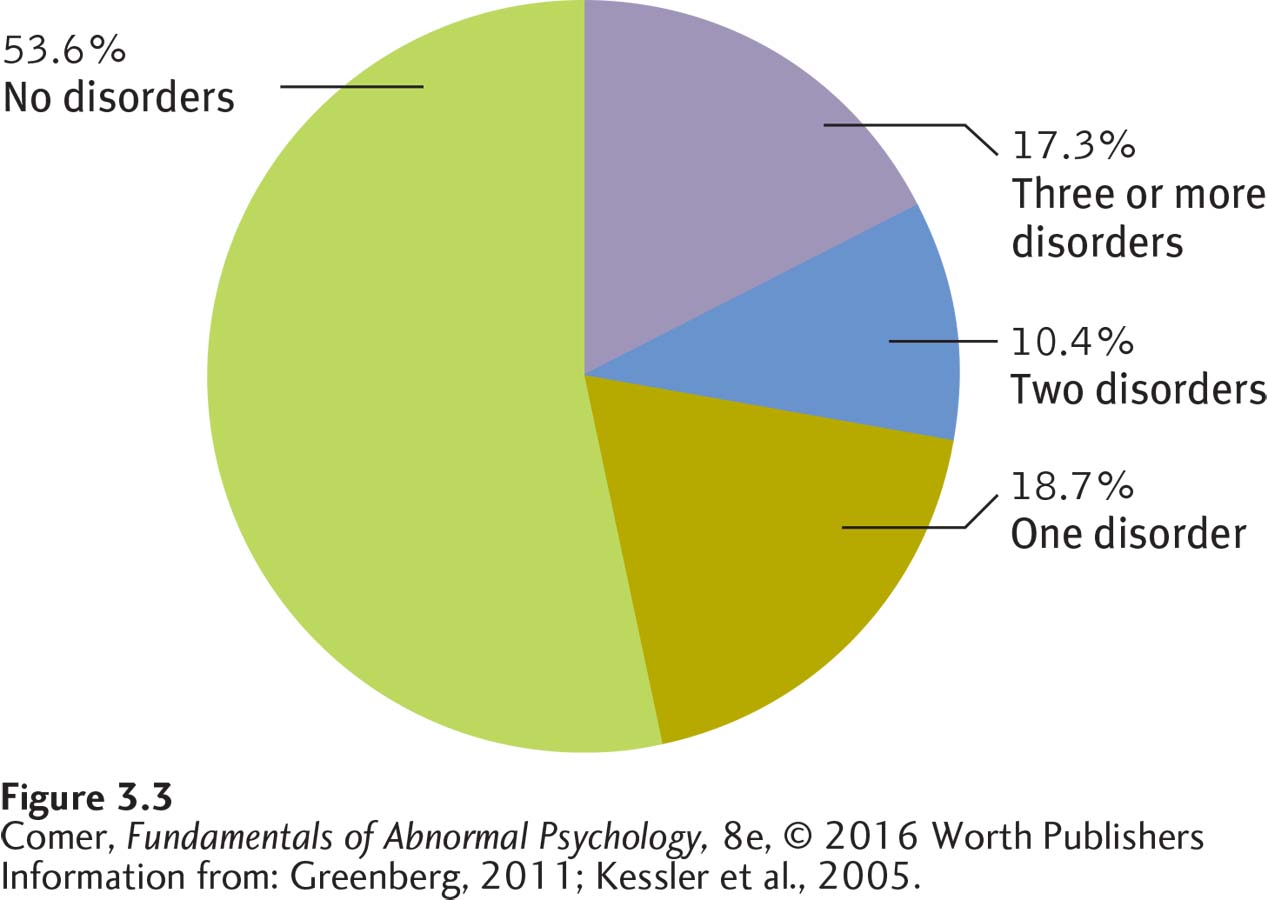

Although people may receive just one diagnosis from the DSM-

Dimensional Information In addition to deciding what disorder a client is displaying, diagnosticians assess the current severity of the client’s disorder—

Additional Information Clinicians also may include other useful information when making a diagnosis. They may, for example, indicate special psychosocial problems the client has. Franco’s recent breakup with his girlfriend might be noted as relationship distress. Altogether, Franco might receive the following diagnosis:

Diagnosis: Major depressive disorder with anxious distress

Severity: Moderate

Additional information: Relationship distress

Each diagnostic category also has a numerical code that clinicians must state—

Is DSM-5 an Effective Classification System?

BETWEEN THE LINES

By the Numbers

| 1 | Number of categories of psychological dysfunctioning listed in the 1840 U.S. census (“idiocy/insanity”) |

| 60 | Number of categories listed in DSM- |

| 541 | Number of categories listed in DSM- |

A classification system, like an assessment method, is judged by its reliability and validity. Here reliability means that different clinicians are likely to agree on the diagnosis when they use the system to diagnose the same client. Early versions of the DSM were at best moderately reliable (Regier et al., 2011). In the early 1960s, for example, four clinicians, each relying on DSM-

The framers of DSM-

The validity of a classification system is the accuracy of the information that its diagnostic categories provide. Categories are of most use to clinicians when they demonstrate predictive validity—that is, when they help predict future symptoms or events. A common symptom of major depressive disorder is either insomnia or excessive sleep. When clinicians give Franco a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, they expect that he may eventually develop sleep problems even if none are present now. In addition, they expect him to respond to treatments that are effective for other depressed persons. The more often such predictions are accurate, the greater a category’s predictive validity.

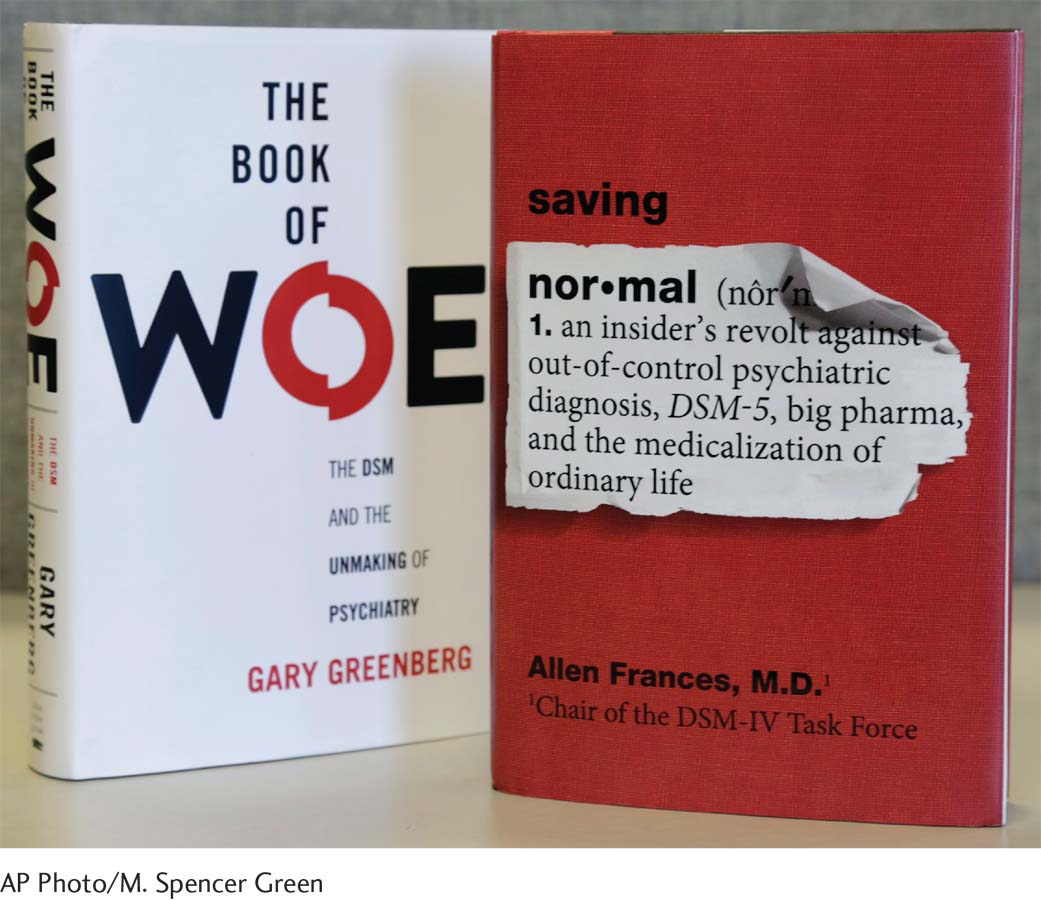

DSM-

Call for Change

The effort to produce DSM-

Some of the key changes in DSM-

BETWEEN THE LINES

New Pop Psychology Labels

“Online disinhibition effect” The tendency of people to show less restraint when on the Internet (Sitt, 2013; Suler, 2004).

“Drunkorexia” A diet fad, particularly among young women, in which the individual restricts food intake during the day so that she can party and get drunk at night without gaining weight from the alcohol (Archer, 2013).

Adding a new category, “autism spectrum disorder,” that combines certain past categories such as “autistic disorder” and “Asperger’s syndrome” (see Chapter 14).

Viewing “obsessive-

compulsive disorder” as a problem that is different from the anxiety disorders and grouping it instead along with other obsessive- compulsive- like disorders such as “hoarding disorder,” “body dysmorphic disorder,” “trichotillomania” (hair- pulling disorder), and “excoriation (skin- picking) disorder” (see Chapter 4). Viewing “posttraumatic stress disorder” as a problem that is distinct from the anxiety disorders (see Chapter 5).

Page 96Adding new categories, “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder,” “persistent depressive disorder,” and “premenstrual dysphoric disorder,” and grouping them with other kinds of depressive disorders (see Chapter 6).

Adding a new category, “somatic symptom disorder” (see Chapter 8).

Replacing the term “hypochondriasis” with the new term “illness anxiety disorder” (see Chapter 8).

Adding a new category, “binge eating disorder” (see Chapter 9).

Adding a new category, “substance use disorder,” that combines past categories “substance abuse” and “substance dependence” (see Chapter 10).

Viewing “gambling disorder” as a problem that should be grouped as an addictive disorder alongside the substance use disorders (see Chapter 10).

Replacing the term “gender identity disorder” with the new term “gender dysphoria” (see Chapter 11).

Replacing the term “mental retardation” with the new term “intellectual disability” (see Chapter 14).

Adding a new category, “specific learning disorder,” that combines past categories “reading disorder,” “mathematics disorder,” and “disorder of written expression” (see Chapter 14).

Replacing the term “dementia” with the new term “neurocognitive disorder” (see Chapter 15).

Adding a new category, “mild neurocognitive disorder” (see Chapter 15).

Can Diagnosis and Labeling Cause Harm?

Even with trustworthy assessment data and reliable and valid classification categories, clinicians will sometimes arrive at a wrong conclusion (Faust & Ahern, 2012; Trull & Prinstein, 2012). Like all human beings, they are flawed information processors. Studies show that they may be overly influenced by information gathered early in the assessment process. In addition, they may pay too much attention to certain sources of information, such as a parent’s report about a child, and too little to others, such as the child’s point of view. Finally, their judgments can be distorted by any number of personal biases—

Why are medical diagnoses usually valued, while the use of psychological diagnoses is often criticized?

BETWEEN THE LINES

Bands with Psychological Labels

Pavlov’s Dog

Pink Freud

Alcoholics Unanimous

Widespread Panic

Madness

Obsession

Bad Brains

Placebo

Fear Factory

Mood Elevator

Neurosis

10,000 Maniacs

Grupo Mania

Unsane

Beyond the potential for misdiagnosis, the very act of classifying people can lead to unintended results. As you read in Chapter 2, for example, many family-

Because of these problems, some clinicians would like to do away with diagnoses. Others disagree. They believe we must simply work to increase what is known about psychological disorders and improve diagnostic techniques. They hold that classification and diagnosis are critical to understanding and treating people in distress.

Summing Up

DIAGNOSIS After collecting assessment information, clinicians form a clinical picture and decide upon a diagnosis. The diagnosis is chosen from a classification system. The system used most widely in North America is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The most recent version of the DSM, known as DSM-

Even with trustworthy assessment data and reliable and valid classification categories, clinicians will not always arrive at the correct conclusion. They are human and so fall prey to various biases, misconceptions, and expectations. Another problem related to diagnosis is the prejudice that labels arouse, which may be damaging to the person who is diagnosed.