6.1 Unipolar Depression: The Depressive Disorders

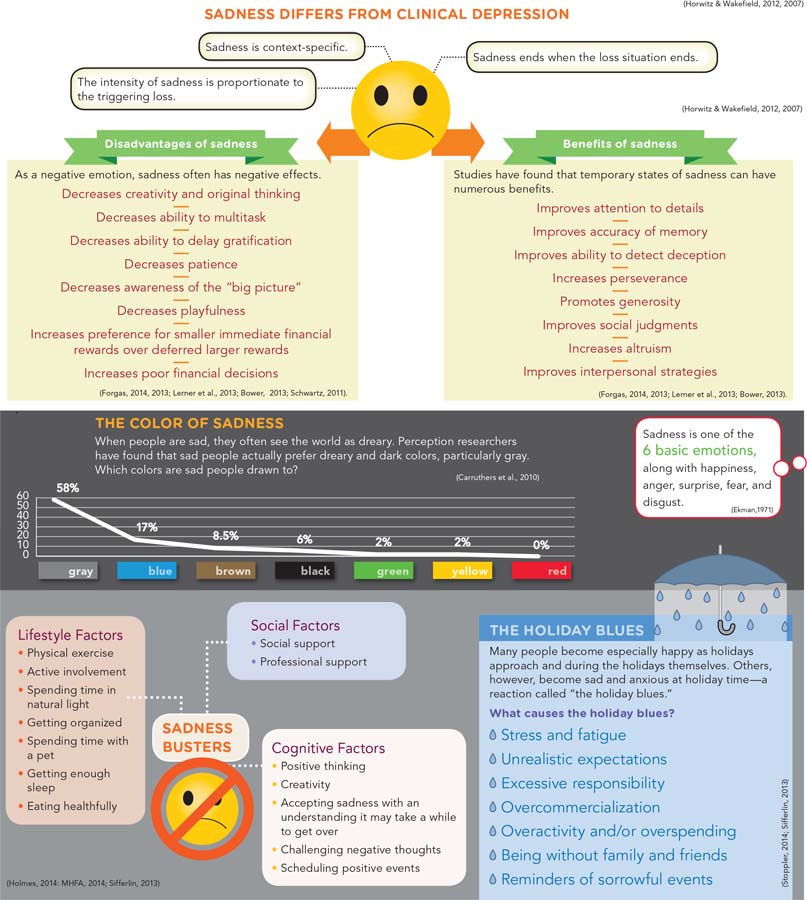

Almost every day we have ups and downs in mood. How can we distinguish the everyday blues from clinical depression?

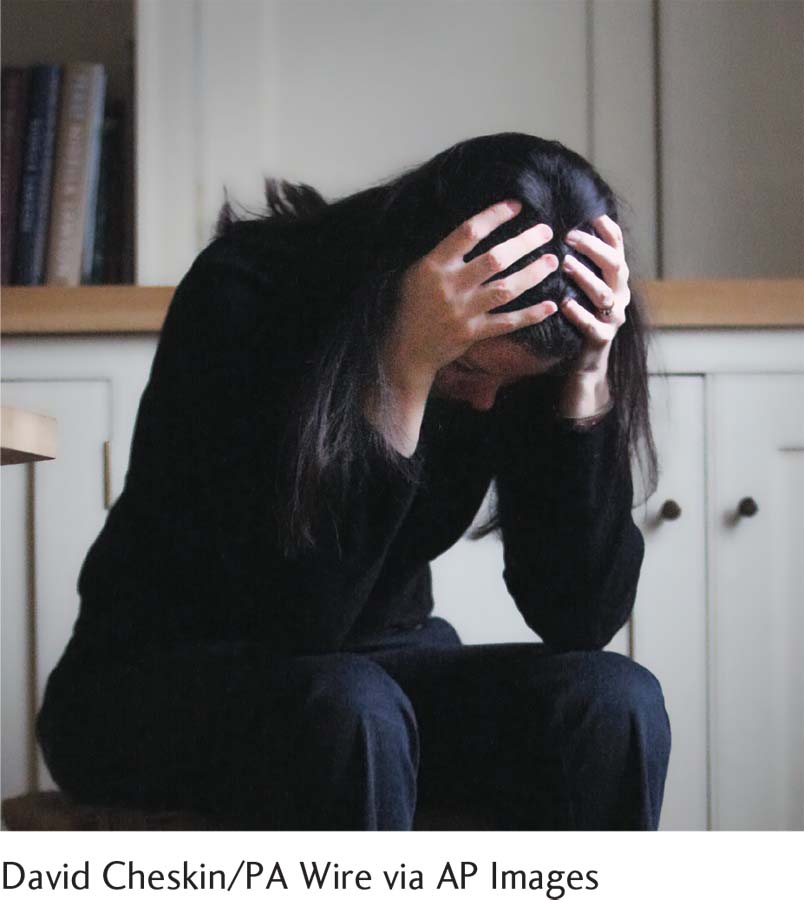

Whenever we feel particularly unhappy, we are likely to describe ourselves as “depressed.” In all likelihood, we are merely responding to sad events, fatigue, or unhappy thoughts. This loose use of the term confuses a perfectly normal mood swing with a clinical syndrome (see InfoCentral). All of us experience dejection from time to time, but only some experience a depressive disorder. Such disorders bring severe and long-

How Common Is Unipolar Depression?

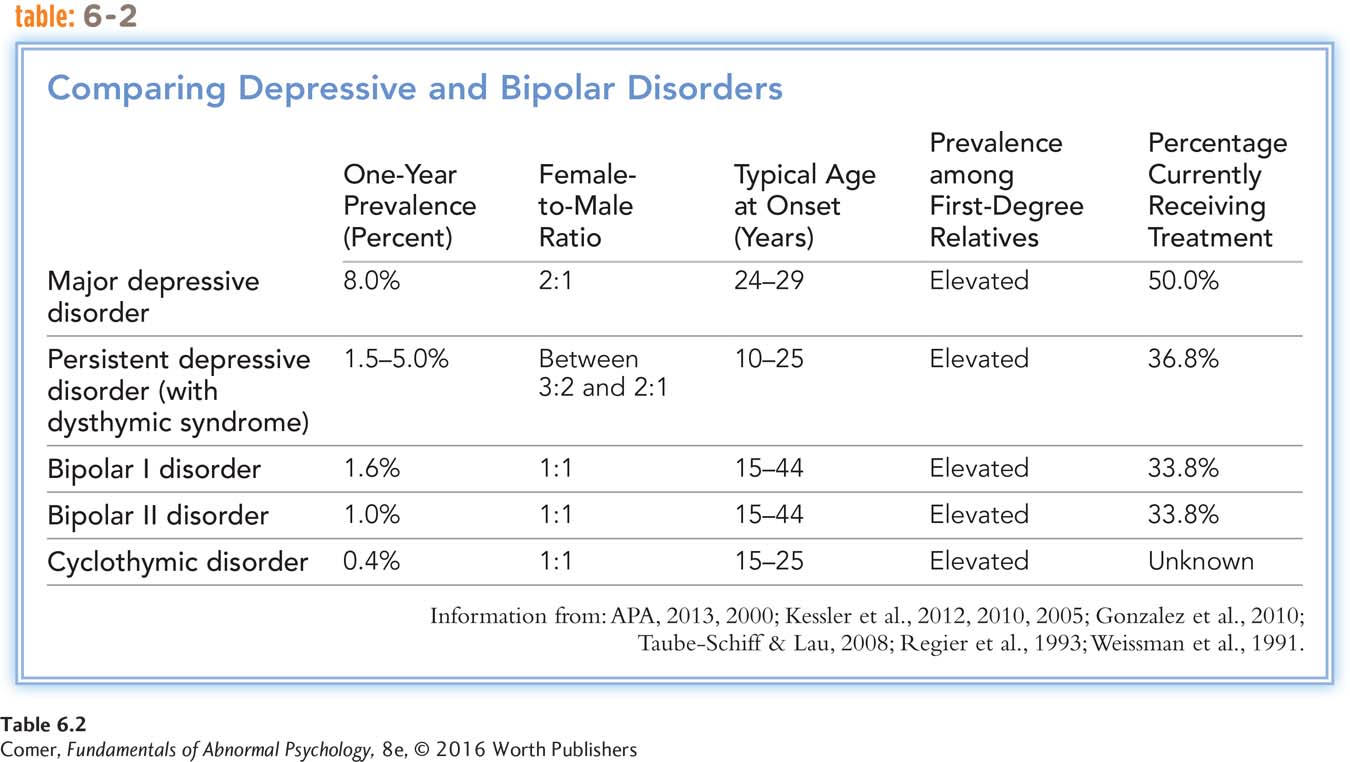

Around 9 percent of adults in the United States suffer from a severe unipolar pattern of depression in any given year, while as many as 5 percent suffer from mild forms (Kessler et al., 2012, 2010). Around 18 percent of all adults experience an episode of severe unipolar depression at some point in their lives. These prevalence rates are similar in Canada, England, and many other countries. Moreover, the rate of depression—

Women are at least twice as likely as men to have episodes of severe unipolar depression (WHO, 2014; Astbury, 2010). As many as 26 percent of women have an episode at some time in their lives, compared with 12 percent of men. As you will see in Chapter 14, among children the prevalence of unipolar depression is similar for girls and boys.

Approximately 85 percent of people with unipolar depression recover, some without treatment. At least 40 percent of them have at least one other episode of depression later in their lives (Halverson et al., 2015; Monroe, 2010).

What Are the Symptoms of Depression?

The picture of depression may vary from person to person. Earlier you saw how Meri’s profound sadness, fatigue, and cognitive deterioration brought her job and social life to a standstill. Some depressed people have symptoms that are less severe. They manage to function, although their depression typically robs them of much effectiveness or pleasure.

As the case of Meri indicates, depression has many symptoms other than sadness. The symptoms, which often exacerbate one another, span five areas of functioning: emotional, motivational, behavioral, cognitive, and physical.

Emotional Symptoms Most people who are depressed feel sad and dejected. They describe themselves as feeling “miserable,” “empty,” and “humiliated.” They tend to lose their sense of humor, report getting little pleasure from anything, and in some cases display anhedonia, an inability to experience any pleasure at all. A number also experience anxiety, anger, or agitation. Terrie Williams, author of Black Pain, a book about depression in African Americans, describes the agony she went through each morning as her depression was unfolding:

InfoCentral

SADNESS

Depression, a clinical disorder that causes considerable distress and impairment, features a range of symptoms, including emotional, motivational, behavioral, cognitive, and physical symptoms. Sadness is often one of the symptoms found in depression, but most often it is a perfectly normal negative emotion triggered by a loss or other painful circumstance.

My mornings were unmanageable. To wake up each morning was to remember once again that the world by which I defined myself was no more. Soon after opening my eyes, the crying bouts would start and I’d sit alone for hours, weeping and mourning my losses.

(Williams, 2008, p. 9)

Motivational Symptoms Depressed people typically lose the desire to pursue their usual activities. Almost all report a lack of drive, initiative, and spontaneity. They may have to force themselves to go to work, talk with friends, eat meals, or have sex. Terrie describes her social withdrawal during a depressive episode:

I woke up one morning with a knot of fear in my stomach so crippling that I couldn’t face light, much less day, and so intense that I stayed in bed for three days with the shades drawn and the lights out.

Three days. Three days not answering the phone. Three days not checking my e-

(Williams, 2008, p. xxiv)

Suicide represents the ultimate escape from life’s challenges. As you will see in Chapter 7, many depressed people become uninterested in life or wish to die; others wish they could kill themselves, and some actually do. It has been estimated that between 6 and 15 percent of people who suffer from severe depression commit suicide (MHF, 2014; Alridge, 2012).

Behavioral Symptoms Depressed people are usually less active and less productive. They spend more time alone and may stay in bed for long periods. One man recalls, “I’d awaken early, but I’d just lie there—

Cognitive Symptoms Depressed people hold extremely negative views of themselves. They consider themselves inadequate, undesirable, inferior, perhaps evil (Lopez Molina et al., 2014). They also blame themselves for nearly every unfortunate event, even things that have nothing to do with them, and they rarely credit themselves for positive achievements.

Another cognitive symptom of depression is pessimism. Sufferers are usually convinced that nothing will ever improve, and they feel helpless to change any aspect of their lives. Because they expect the worst, they are likely to procrastinate. Their sense of hopelessness and helplessness makes them especially vulnerable to suicidal thinking (Shiratori et al., 2014).

People with depression frequently complain that their intellectual ability is poor. They feel confused, unable to remember things, easily distracted, and unable to solve even the smallest problems. In laboratory studies, depressed people do perform more poorly than nondepressed people on some tasks of memory, attention, and reasoning (Chen et al., 2013). It may be, however, that these difficulties sometimes reflect motivational problems rather than cognitive ones.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Given the choice between the experience of pain and nothing, I would choose pain.”

William Faulkner

Physical Symptoms People who are depressed frequently have such physical ailments as headaches, indigestion, constipation, dizzy spells, and general pain (Bai et al., 2014; Goldstein et al., 2011). In fact, many depressions are misdiagnosed as medical problems at first (Parker & Hyett, 2010). Disturbances in appetite and sleep are particularly common (Jackson et al., 2014). Most depressed people eat less, sleep less, and feel more fatigued than they did prior to the disorder. Some, however, eat and sleep excessively.

Diagnosing Unipolar Depression

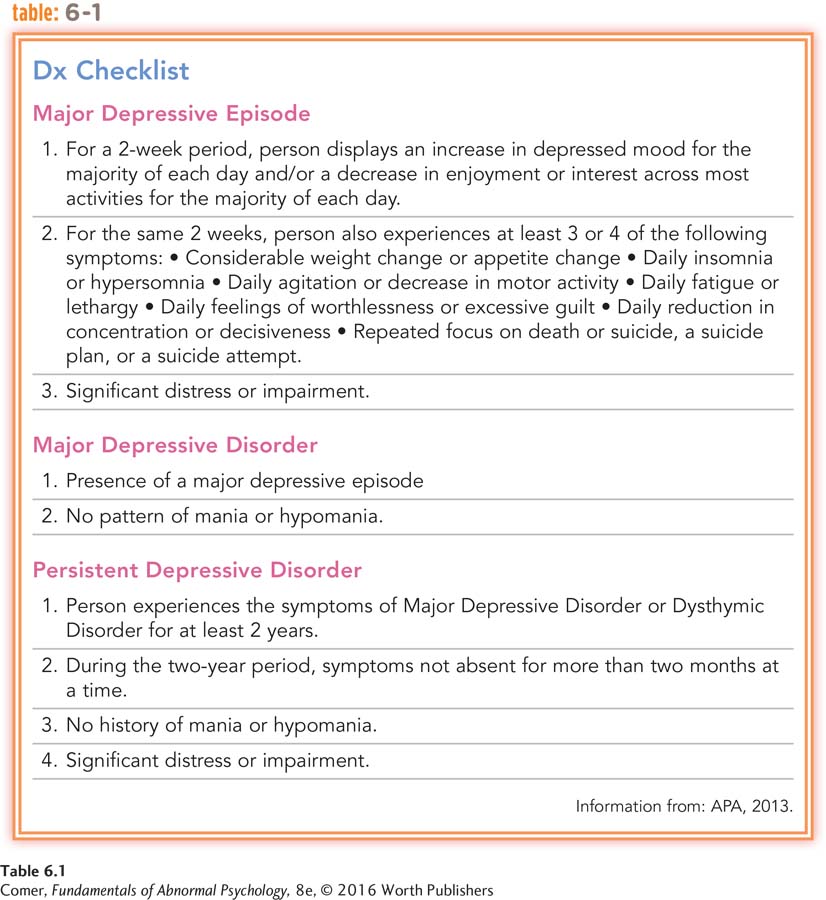

According to DSM-

major depressive disorder A severe pattern of depression that is disabling and is not caused by such factors as drugs or a general medical condition.

DSM-

persistent depressive disorder A chronic form of unipolar depression marked by ongoing and repeated symptoms of either major or mild depression.

People whose unipolar depression is particularly long-

premenstrual dysphoric disorder A disorder marked by repeated episodes of significant depression and related symptoms during the week before menstruation.

A third type of depressive disorder is premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a diagnosis given to certain women who repeatedly have clinically significant depressive and related symptoms during the week before menstruation. The inclusion of this pattern in DSM-

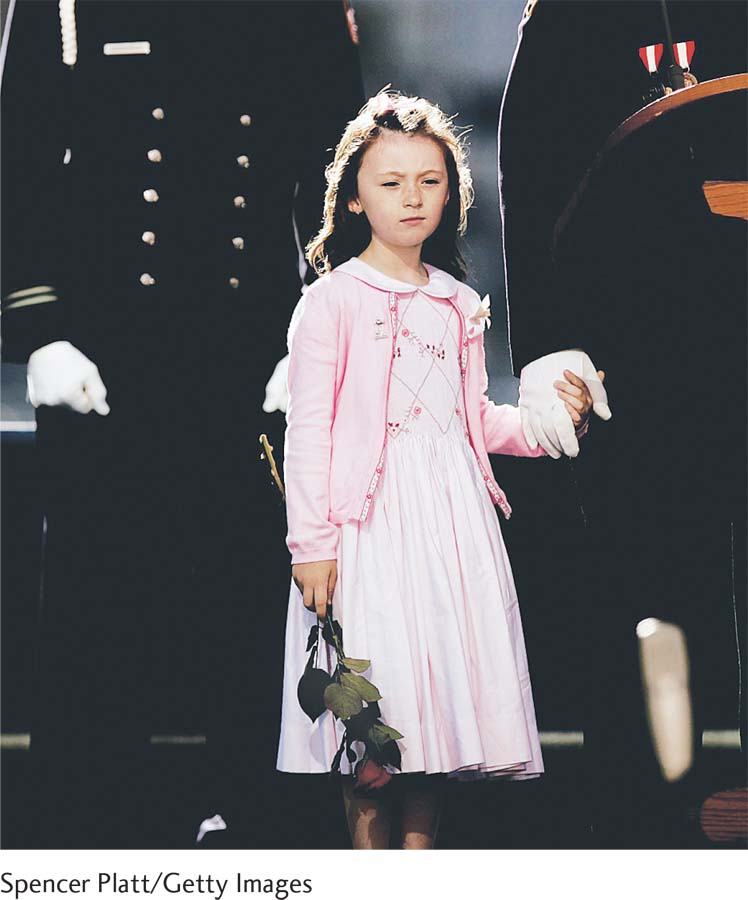

Yet another kind of depressive disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, is characterized by a combination of persistent depressive symptoms and recurrent outbursts of severe temper. This disorder emerges during mid-

Stress and Unipolar Depression

Episodes of unipolar depression often seem to be triggered by stressful events (Fried et al., 2015). In fact, researchers have found that depressed people have a larger number of stressful life events during the month just before the onset of their disorder than do other people during the same period of time. Of course, stressful life events also precede other psychological disorders, but depressed people often report more such events than anybody else.

Why do you think stressful events or periods in life might trigger depressed feelings and other negative emotions?

Some clinicians consider it important to distinguish a reactive (exogenous) depression, which follows clear-

The Biological Model of Unipolar Depression

BETWEEN THE LINES

Medical Problems and Depression

| 50% | Stroke victims who experience clinical depression |

| 30% | Cancer patients who experience depression |

| 20% | Heart attack victims who become depressed |

| 18% | People with diabetes who are depressed |

(Udesky, 2014; Jiang et al., 2011; Kerber et al., 2011; NIMH, 2004)

Medical researchers have been aware for years that certain diseases and drugs produce mood changes. Could unipolar depression itself have biological causes? Evidence from genetic, biochemical, anatomical, and immune system studies suggests that often it does.

Genetic Factors Four kinds of research—

If a predisposition to unipolar depression is inherited, you might also expect to find a particularly large number of cases among the close relatives of a proband. Twin studies have supported this expectation (Levinson & Nichols, 2014). One study looked at nearly 200 pairs of twins. When an identical twin had unipolar depression, there was a 46 percent chance that the other twin would have the same disorder. In contrast, when a fraternal twin had unipolar depression, the other twin had only a 20 percent chance of developing the disorder (McGuffin et al., 1996).

Finally, today’s scientists have at their disposal techniques from the field of molecular biology to help them directly identify genes and determine whether certain gene abnormalities are related to depression. Using such techniques, researchers have found evidence that unipolar depression may be tied to genes on chromosomes 1, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, and X (Jansen et al., 2015; Preuss et al., 2013). For example, a number of researchers have found that people who are depressed often have an abnormality of their 5-

norepinephrine A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression and panic disorder.

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive-

Biochemical Factors Low activity of two neurotransmitter chemicals, norepinephrine and serotonin, has been strongly linked to unipolar depression. In the 1950s, several pieces of evidence began to point to this relationship. First, medical researchers discovered that certain medications for high blood pressure often caused depression (Ayd, 1956). As it turned out, some of these medications lowered norepinephrine activity and others lowered serotonin. A second piece of evidence was the discovery of the first truly effective antidepressant drugs. Although these drugs were discovered by accident, researchers soon learned that they relieve depression by increasing either norepinephrine or serotonin activity.

For years it was thought that low activity of either norepinephrine or serotonin was capable of producing depression, but investigators now believe that their relation to depression is more complicated (Ding et al., 2014; Goldstein et al., 2011). Research suggests that interactions between serotonin and norepinephrine activity, or between these and other kinds of neurotransmitters in the brain, rather than the operation of any one neurotransmitter alone, may account for unipolar depression.

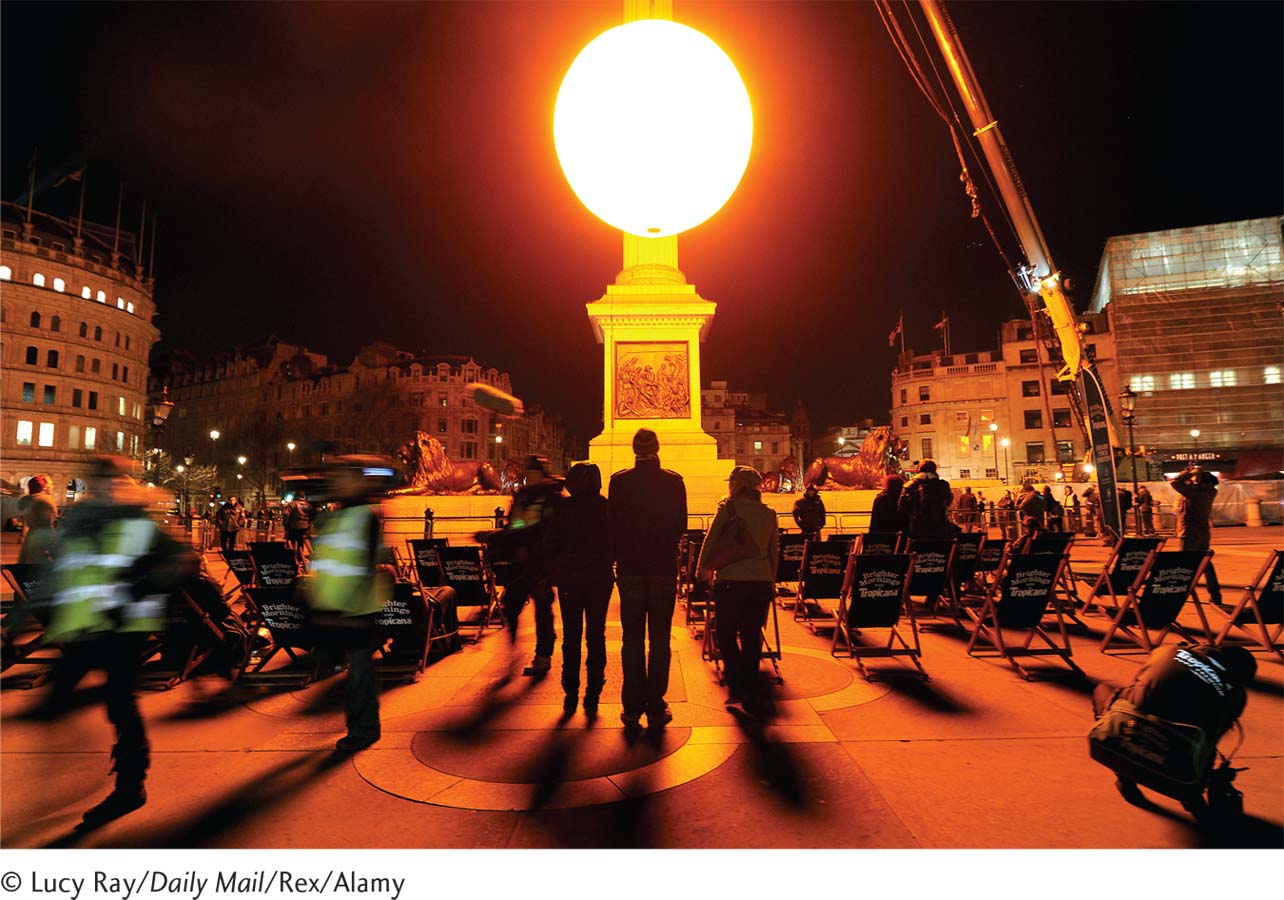

Biological researchers have also learned that the body’s endocrine system may play a role in unipolar depression (see PsychWatch). As you have seen, endocrine glands throughout the body release hormones, chemicals that in turn spur body organs into action (see Chapter 5). People with unipolar depression have been found to have abnormally high levels of cortisol, one of the hormones released by the adrenal glands during times of stress (Owens et al., 2014; Treadway & Pizzagalli, 2014). This relationship is not all that surprising, given that stressful events often seem to trigger depression. Another hormone that has been tied to depression is melatonin, sometimes called the “Dracula hormone” because it is released only in the dark. People who experience a recurrence of depression each winter (a pattern called seasonal affective disorder) may secrete more melatonin during the winter’s long nights than other individuals do.

PsychWatch

Sadness at the Happiest of Times

Women usually expect the birth of a child to be a happy experience. But for 10 to 30 percent of new mothers, the weeks and months after childbirth bring clinical depression (Guintivano et al., 2014). Peripartum depression, popularly called postpartum depression, typically begins within four weeks after the birth of a child; many cases actually begin during pregnancy (APA, 2013). This disorder is far more severe than simple “baby blues.” It is also different from other postpartum syndromes such as postpartum psychosis, a problem that is examined in Chapter 12.

The “baby blues” are so common—

In postpartum depression, however, depressive symptoms continue and may last up to a year or more. The symptoms include extreme sadness, despair, tearfulness, insomnia, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, compulsions, panic attacks, feelings of inability to cope, and suicidal thoughts. Women who have an episode of postpartum depression have a 25 to 50 percent chance of developing it again with a subsequent birth (Stevens et al., 2002).

Many clinicians believe that the hormonal changes accompanying childbirth trigger postpartum depression. All women go through a kind of hormone “withdrawal” after delivery, as estrogen and progesterone levels, which rise as much as 50 times above normal during pregnancy, now drop sharply to levels far below normal (Horowitz et al., 2005, 1995). Perhaps some women are particularly influenced by these dramatic hormone changes (Mehta et al., 2014). Other theorists suggest that some women may have a genetic predisposition to postpartum depression (Guintivano et al., 2014).

At the same time, psychological and sociocultural factors may play important roles in the disorder (Mauthner, 2010). The birth of a baby brings enormous changes for women—

Fortunately, treatment can make a big difference for most women with postpartum depression. Self-

However, many women who would benefit from treatment do not seek help because they feel ashamed about being sad at a time that is supposed to be joyous and are concerned about being judged harshly (Bina, 2014; Mauthner, 2010). For them, a large dose of education is in order. Even positive events, such as the birth of a child, can be stressful if they also bring major change to one’s life. Recognizing and addressing such feelings are in everyone’s best interest.

Still other biological researchers are starting to believe that unipolar depression is tied more closely to what happens within neurons than to the chemicals that carry messages between neurons. They believe that activity by key neurotransmitters or hormones ultimately leads to deficiencies of certain proteins and other chemicals within neurons—

The biochemical explanations of unipolar depression have produced much enthusiasm, but research in this area has certain limitations. Some of it has relied on analogue studies, which create depression-

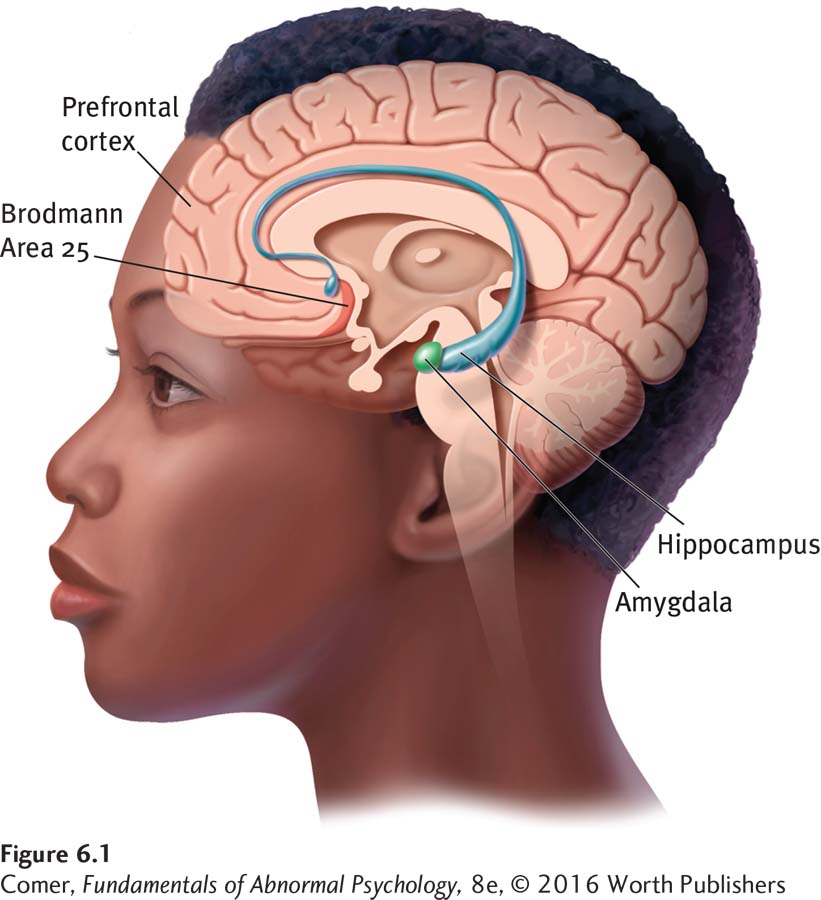

Brain Anatomy and Brain Circuits In earlier chapters, you read that many biological researchers now believe that emotional reactions of various kinds are tied to brain circuits—networks of brain structures that work together, triggering each other into action and producing a particular kind of emotional reaction. Although research is far from complete, a brain circuit responsible for unipolar depression has begun to emerge (Treadway & Pizzagalli, 2014; Brockmann et al., 2011). An array of brain-

The Immune System As you will see in Chapter 8, the immune system is the body’s network of activities and body cells that fight off bacteria, viruses, and other foreign invaders. When people are under intense stress for a while, their immune systems may become dysregulated, leading to lower functioning of important white blood cells called lymphocytes and to increased production of C-

What Are the Biological Treatments for Unipolar Depression? Usually biological treatment means antidepressant drugs or popular herbal supplements, but for severely depressed people who do not respond to other forms of treatment, it sometimes means electroconvulsive therapy, or a relatively new group of approaches called brain stimulation.

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) A treatment for depression in which electrodes attached to a patient’s head send an electrical current through the brain, causing a convulsion.

ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY One of the most controversial forms of treatment for depression is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). In this procedure, two electrodes are attached to the patient’s head, and 65 to 140 volts of electricity are passed through the brain for half a second or less. This results in a brain seizure that lasts from 25 seconds to a few minutes. After 6 to 12 such treatments, spaced over two to four weeks, most patients feel less depressed (Fink, 2014, 2007).

The discovery that electric shock can be therapeutic was made by accident. In the 1930s, clinical researchers mistakenly came to believe that brain seizures, or the convulsions (severe body spasms) that accompany them, could cure schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, and so they searched for ways to induce seizures as a treatment for patients with psychosis. One early technique was to give patients the drug metrazol. Another was to give them large doses of insulin (insulin coma therapy). These procedures produced the desired brain seizures, but each was quite dangerous and sometimes even caused death. Finally, an Italian psychiatrist named Ugo Cerletti discovered that he could produce seizures more safely by applying electric currents to a patient’s head. ECT soon became popular and was tried out on a wide range of psychological problems, as new techniques so often are. Its effectiveness with severe depression in particular became apparent.

In the early years of ECT, broken bones and dislocations of the jaw or shoulders sometimes resulted from patients’ severe convulsions. Today’s practitioners avoid these problems by giving patients strong muscle relaxants to minimize convulsions. They also use anesthetics to put patients to sleep during the procedure, reducing their terror.

Patients who receive ECT often have difficulty remembering certain events, most often events that took place immediately before and after their treatments (Martin et al., 2015; Merkl et al., 2011). In most cases, this memory loss clears up within a few months, but some patients are left with gaps in more distant memory, and this form of amnesia can be permanent (Hanna et al., 2009; Wang, 2007).

ECT is clearly effective in treating unipolar depression, although it has been difficult to determine why it works so well (Baldinger et al., 2014; Fink et al., 2014). The procedure seems to be particularly effective in cases of depression that include delusions (Rothschild, 2010).

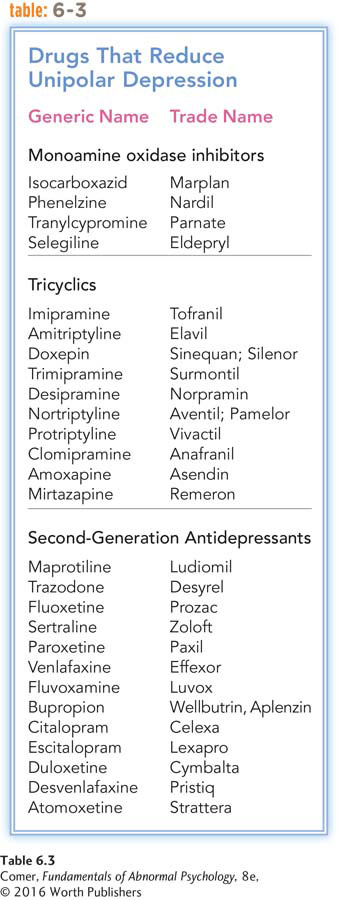

ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS Two kinds of drugs discovered in the 1950s reduce the symptoms of depression: monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and tricyclics. These drugs have now been joined by a third group, the so-

MAO inhibitor An antidepressant drug that prevents the action of the enzyme monoamine oxidase.

The effectiveness of MAO inhibitors as a treatment for unipolar depression was discovered accidentally. Physicians noted that iproniazid, a drug being tested on patients with tuberculosis, had an interesting effect: it seemed to make the patients happier (Sandler, 1990). It was found to have the same effect on depressed patients (Kline, 1958; Loomer et al., 1957). What this and several related drugs had in common biochemically was that they slowed the body’s production of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). Thus they were called MAO inhibitors.

Normally, brain supplies of the enzyme MAO break down, or degrade, the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. MAO inhibitors block MAO from carrying out this activity and thereby stop the destruction of norepinephrine. The result is a rise in norepinephrine activity and, in turn, a reduction of depressive symptoms. Approximately half of depressed patients who take MAO inhibitors are helped by them (Ciraulo et al., 2011; Thase et al., 1995). There is, however, a potential danger with regard to these drugs. When people who take MAO inhibitors eat foods containing the chemical tyramine—including such common foods as cheeses, bananas, and certain wines—

tricyclic An antidepressant drug such as imipramine that has three rings in its molecular structure.

The discovery of tricyclics in the 1950s was also accidental. Researchers who were looking for a new drug to combat schizophrenia ran some tests on a drug called imipramine (Kuhn, 1958). They discovered that imipramine was of no help in cases of schizophrenia, but it did relieve unipolar depression in many people. The new drug (trade name Tofranil) and related ones became known as tricyclic antidepressants because they all share a three-

In hundreds of studies, depressed patients taking tricyclics have improved much more than similar patients taking placebos, although the drugs must be taken for at least 10 days before such improvements take hold (Advokat et al., 2014). About 65 percent of patients who take tricyclics are helped by them (FDA, 2014). If the patients stop taking tricyclics immediately after obtaining relief, they run a high risk of relapsing within a year. If, however, they continue taking the drugs for five months or more after being free of depressive symptoms—

If antidepressant drugs are effective, why do many people seek out herbal supplements for depression?

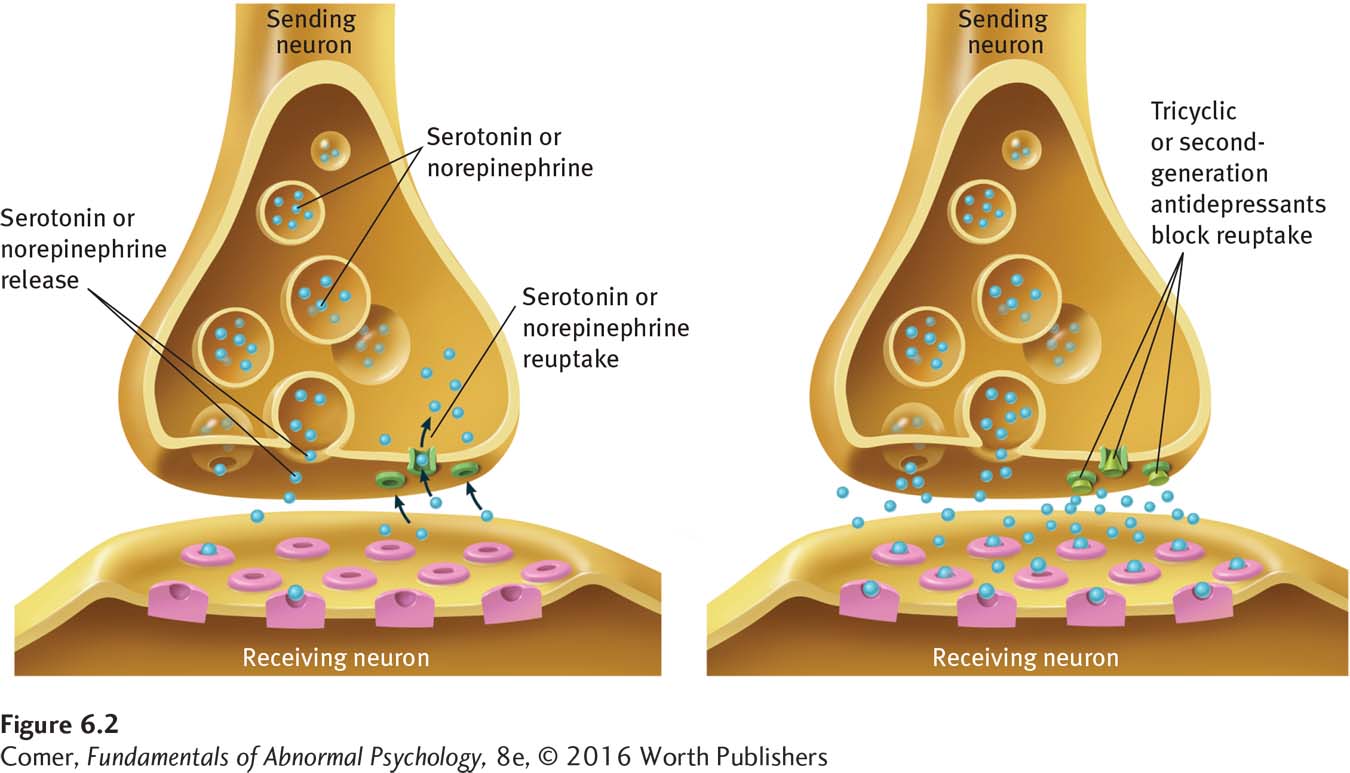

Most researchers have concluded that tricyclics reduce depression by acting on neurotransmitter “reuptake” mechanisms (Ciraulo et al., 2011). Remember from Chapter 2 that messages are carried from the “sending” neuron across the synaptic space to a receiving neuron by a neurotransmitter, a chemical released from the axon ending of the sending neuron. However, there is a complication in this process. While the sending neuron releases the neurotransmitter, a pumplike mechanism in the neuron’s ending immediately starts to reabsorb it in a process called reuptake. The purpose of this reuptake process is to control how long the neurotransmitter remains in the synaptic space and to prevent it from overstimulating the receiving neuron. Unfortunately, the reuptake mechanism may be too successful in some people—

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) A group of second-

A third group of effective antidepressant drugs, structurally different from the MAO inhibitors and tricyclics, has been developed during the past few decades. Most of these second-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Publication Bias

A review of 74 FDA-

In effectiveness and speed of action, the second-

As popular as the antidepressants are, it is important to recognize that they do not work for everyone. In fact, as you have read, even the most successful of them fails to help at least 35 percent of clients with depression. In fact, some recent reviews have raised the possibility that the failure rate is higher still (Hegerl et al., 2012; Isacsson & Alder, 2012). How are clients who do not respond to antidepressant drugs treated currently? Researchers have noted that, all too often, their psychiatrists or family physicians simply prescribe alternative antidepressants or antidepressant mixtures—

[S]he spoke, in a wistful manner, of how she wished her treatment could have been different. “I do wonder what might have happened if [at age 16] I could have just talked to someone, and they could have helped me learn about what I could do on my own to be a healthy person…. Instead, it was you have this problem with your neurotransmitters, and so here, take this pill Zoloft, and when that didn’t work, it was take this pill Prozac, and when that didn’t work, it was take this pill Effexor, and then when I started having trouble sleeping, it was take this sleeping pill,” she says, her voice sounding more wistful than ever. “I am so tired of the pills.”

(Whitaker, 2010)

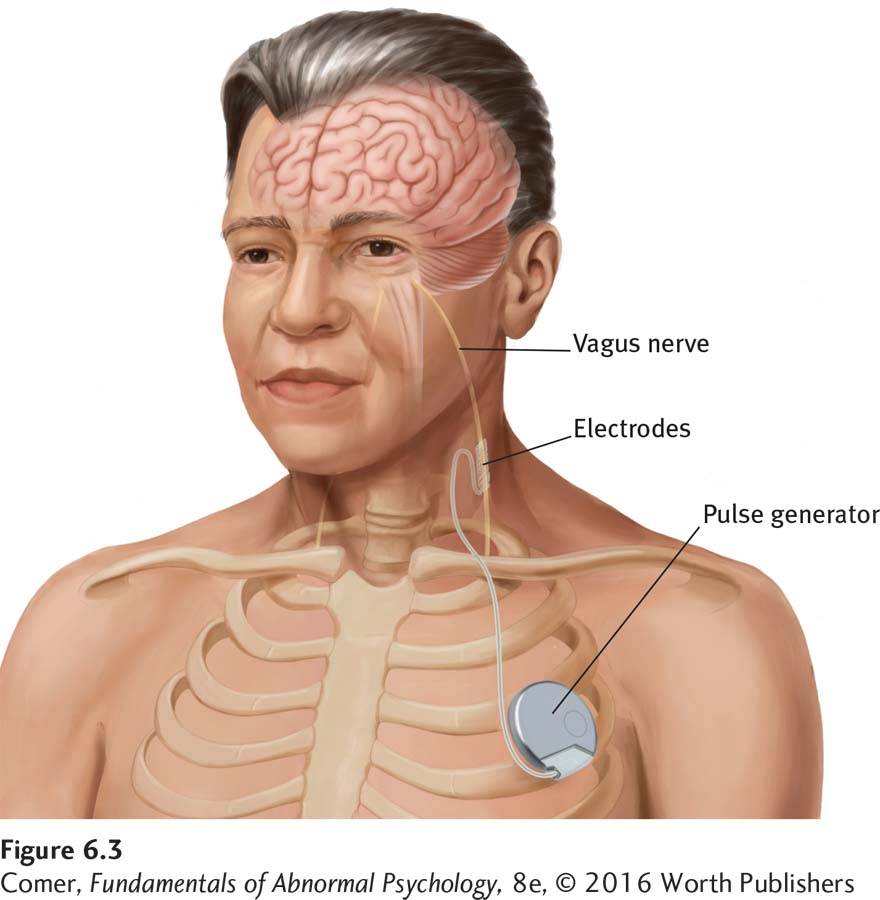

BRAIN STIMULATION In recent years, three additional biological approaches have been developed for the treatment of depressive disorders—

vagus nerve stimulation A treatment procedure for depression in which an implanted pulse generator sends regular electrical signals to a person’s vagus nerve; the nerve then stimulates the brain.

The vagus nerve, the longest nerve in the human body, runs from the brain stem through the neck down the chest and on to the abdomen. A number of years ago, a group of depression researchers surmised that they might be able to stimulate the brain by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve with ECT. Their efforts gave birth to a new treatment for depression—

In this procedure, a surgeon implants a small device called a pulse generator under the skin of the chest. The surgeon then guides a wire, which extends from the pulse generator, up to the neck and attaches it to the vagus nerve (see Figure 6.3). Electrical signals travel from the pulse generator through the wire to the vagus nerve. The stimulated vagus nerve then delivers electrical signals to the brain. In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved this procedure.

Ever since vagus nerve stimulation was first tried on depressed human beings, research has found that it brings significant relief to many depressed people. In fact, in studies of severely depressed people who have not responded to any other form of treatment, as many as 40 percent improve significantly when treated with this procedure (Howland, 2014; Berry et al., 2013).

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) A treatment procedure for depression in which an electromagnetic coil, which is placed on or above a patient’s head, sends a current into the individual’s brain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is another technique that is used to try to stimulate the brain without subjecting depressed patients to the undesired effects or trauma of ECT. In this procedure, the clinician places an electromagnetic coil on or above the patient’s head. The coil sends a current into the prefrontal cortex. As you’ll remember, some parts of the prefrontal cortex of depressed people are underactive; TMS appears to increase neuron activity in those regions. A number of studies have found that TMS reduces depression for many patients when it is administered daily for two to four weeks (Dunner et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2012).

deep brain stimulation (DBS) A treatment procedure for depression in which a pacemaker powers electrodes that have been implanted in Brodmann Area 25, thus stimulating that brain area.

As you read earlier, researchers have recently linked depression to high activity in Brodmann Area 25. This finding led neurologist Helen Mayberg and her colleagues (2005) to administer an experimental treatment called deep brain stimulation (DBS) to six severely depressed patients who had previously been unresponsive to all other forms of treatment. The Mayberg team drilled two tiny holes into the patient’s skull and implanted electrodes in Area 25. The electrodes were connected to a battery, or “pacemaker,” that was implanted in the patient’s chest (for men) or stomach (for women). The pacemaker powered the electrodes, sending a steady stream of low-

In the initial study of DBS, four of the six severely depressed patients became almost depression-

Psychological Models of Unipolar Depression

The psychological models that have been most widely applied to unipolar depression are the psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive models. The psychodynamic model has not been strongly supported by research, and the behavioral model has received moderate support. In contrast, the cognitive model has received considerable research support and gained a large following.

The Psychodynamic Model Sigmund Freud (1917) and his student Karl Abraham (1916, 1911) developed the first psychodynamic explanation and treatment for depression. Their emphasis on dependence and loss continues to influence today’s psychodynamic clinicians.

Why do you think so many comedians and other entertainers report having been depressed earlier in their lives?

PSYCHODYNAMIC EXPLANATIONS Freud and Abraham began by noting the similarity between clinical depression and grief in people who lose loved ones: constant weeping, loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping, loss of pleasure in life, and social withdrawal. According to the theorists, a series of unconscious processes is set in motion when a loved one dies. Unable to accept the loss, mourners at first regress to the oral stage of development, the period of total dependency when infants cannot distinguish themselves from their parents. By regressing to this stage, the mourners merge their own identity with that of the person they have lost, and so symbolically regain the lost person. They direct all their feelings for the loved one, including sadness and anger, toward themselves. For most mourners, this reaction is temporary. For some, however, grief worsens over time, and they, in fact, become depressed.

symbolic loss According to Freudian theory, the loss of a valued object (for example, a loss of employment) that is unconsciously interpreted as the loss of a loved one. Also called imagined loss.

BETWEEN THE LINES

DSM-

In past editions of the DSM, people who lose a loved one were excluded from receiving a diagnosis of major depressive disorder during the first 2 months of their bereavement. However, according to DSM-

Of course, many people become depressed without losing a loved one. To explain why, Freud proposed the concept of symbolic loss, or imagined loss, in which a person equates other kinds of events with the loss of a loved one. A college student may, for example, experience failure in a calculus course as the loss of her parents, believing that they love her only when she excels academically.

Although many psychodynamic theorists have parted company with Freud and Abraham’s theory of depression, it continues to influence current psychodynamic thinking (Desmet, 2013; Zuckerman, 2011). For example, object relations theorists (the psychodynamic theorists who emphasize relationships) propose that depression results when people’s relationships leave them feeling unsafe and insecure (Schattner & Sharar, 2011; Blatt, 2004). People whose parents pushed them toward either excessive dependence or excessive self-

The following description by the therapist of a depressed middle-

Marie Carls ….ad always felt very attached to her mother…. She always tried to placate her volcanic [emotions], to please her in every possible way….

After marriage [to Julius], she continued her pattern of submission and compliance. Before her marriage she had difficulty in complying with a volcanic mother, and after her marriage she almost automatically assumed a submissive role….

[W]hen she was thirty years old ….Marie] and her husband invited Ignatius, who was single, to come and live with them. Ignatius and [Marie] soon discovered that they had an attraction for each other. They both tried to fight that feeling; but when Julius had to go to another city for a few days, the so-

Her suffering had become more acute as she [came to believe] that old age was approaching and she had lost all her chances. Ignatius remained as the memory of lost opportunities…. Her life of compliance and obedience had not permitted her to reach her goal…. When she became aware of these ideas, she felt even more depressed…. She felt that everything she had built in her life was false or based on a false premise.

(Arieti & Bemporad, 1978, pp. 275–

Studies have offered general support for the psychodynamic idea that major losses, especially ones suffered early in life, may set the stage for later depression (Gilman, 2013; Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011). When, for example, a depression scale was administered to 1,250 medical patients during visits to their family physicians, the patients whose fathers had died during their childhood scored higher on depression (Barnes & Prosen, 1985). At the same time, research does not indicate that loss is always at the core of depression. In fact, it is estimated that less than 10 percent of all people who have major losses in life actually become depressed (Bonanno, 2004; Paykel & Cooper, 1992). Moreover, research into the loss–

WHAT ARE THE PSYCHODYNAMIC TREATMENTS FOR UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION? Believing that unipolar depression results from unconscious grief over real or imagined losses, compounded by excessive dependence on other people, psychodynamic therapists seek to help clients bring these underlying issues to consciousness and work through them. They encourage the depressed client to associate freely during therapy; suggest interpretations of the client’s associations, dreams, and displays of resistance and transference; and help the person review past events and feelings (Busch et al., 2004). Free association, for example, helped one man recall the early experiences of loss that, according to his therapist, had set the stage for his depression:

Among his earliest memories, possibly the earliest of all, was the recollection of being wheeled in his baby cart under the elevated train structure and left there alone. Another memory that recurred vividly during the analysis was of an operation around the age of five. He was anesthetized and his mother left him with the doctor. He recalled how he had kicked and screamed, raging at her for leaving him.

(Lorand, 1968, pp. 325–

Despite successful case reports such as this, researchers have found that long-

The Behavioral Model Behaviorists believe that unipolar depression results from significant changes in the number of rewards and punishments people receive in their lives, and they treat depressed people by helping them build more desirable patterns of reinforcement (Dygdon & Dienes, 2013). Clinical researcher Peter Lewinsohn was one of the first clinical theorists to develop a behavioral explanation (Lewinsohn et al., 1990, 1984).

THE BEHAVIORAL EXPLANATION Lewinsohn suggested that the positive rewards in life dwindle for some people, leading them to perform fewer and fewer constructive behaviors. The rewards of campus life, for example, disappear when a young woman graduates from college and takes a job; and an aging baseball player loses the rewards of high salary and adulation when his skills deteriorate. Although many people manage to fill their lives with other forms of gratification, some become particularly disheartened. The positive features of their lives decrease even more, and the decline in rewards leads them to perform still fewer constructive behaviors. In this manner, they spiral toward depression.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Loss of Confidants

Intimate social contact has been declining over the past 30 years. When research participants were asked in 1985 how many confidants they turned to for discussion of important matters, most answered 3. Today, the most common response to the same question is 2 (Bryner, 2011; McPherson, Smith-

In a number of studies, behaviorists have found that the number of rewards people receive in life is indeed related to the presence or absence of depression. Not only do depressed participants typically report fewer positive rewards than nondepressed participants, but when their rewards begin to increase, their mood improved as well (Bylsma et al., 2011; Lewinsohn et al., 1979). Similarly, other investigations have found a strong relationship between positive life events and feelings of life satisfaction and happiness (Carvalho & Hopko, 2011).

Lewinsohn and other behaviorists have further proposed that social rewards are particularly important in the downward spiral of depression (Martell et al., 2010). This claim has been supported by research showing that depressed persons receive fewer social rewards than nondepressed persons and that as their mood improves, their social rewards increase. Although depressed people are sometimes the victims of social circumstances (see MediaSpeak below), it may also be that their dark mood and flat behaviors help produce a decline in social rewards (Constantino et al., 2012; Coyne, 2001).

MediaSpeak

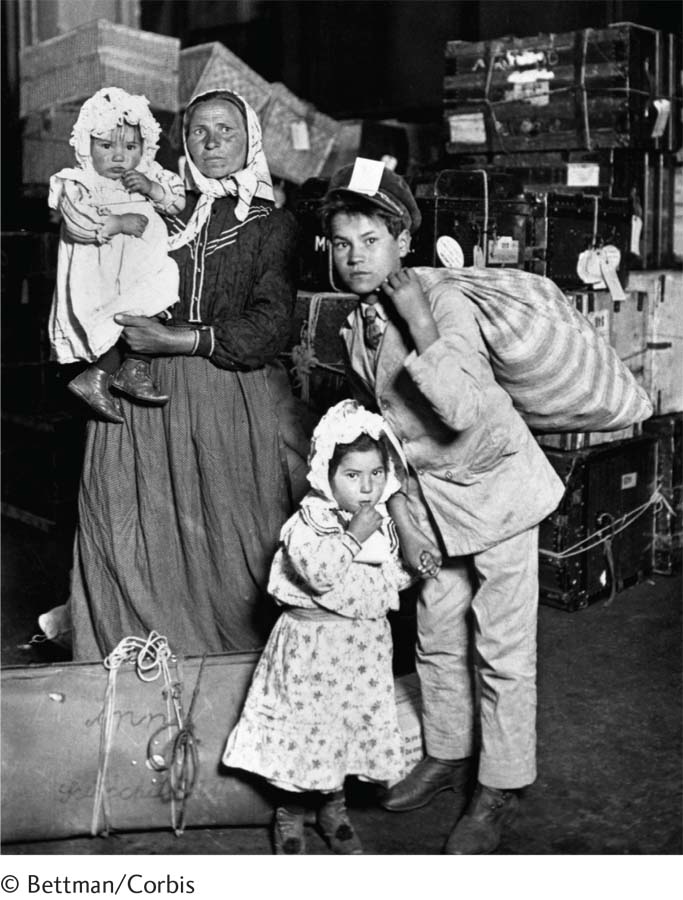

Immigration and Depression in the 21st Century

By Andrew Solomon, New York Times, December 8, 2013

A Canadian woman was denied entry to the United States last month because she had been hospitalized for depression in 2012. Ellen Richardson could not visit, she was told, unless she obtained “medical clearance” from one of three Toronto doctors approved by the Department of Homeland Security. Endorsement by her own psychiatrist, which she could presumably have obtained more efficiently, “would not suffice.” She had been en route to New York, where she had intended to board a cruise to the Caribbean….

The border agent told her he was acting in accordance with the United States Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 212, which allows patrols to block people from visiting the United States if they have a physical or mental disorder that threatens anyone’s “property, safety or welfare.” The [Toronto] Star reported that the agent produced a signed document stating that Ms. Richardson would need a medical evaluation because of her “mental illness episode.” …

This is not the first time such measures have been reported. In 2011, Lois Kamenitz, a Canadian and a former teacher, was barred from entering the United States because she had once attempted suicide. [A police official] told the Star that he had heard of eight similar cases that year. After the incident, he wrote to me: “My sense is that there are a great many people being turned away….”

People in treatment for mental illnesses do not have a higher rate of violence than people without mental illnesses. Furthermore, depression affects one in 10 American adults…. Pillorying depression is regressive, a swoop back into a period when any sign of mental illness was the basis for social exclusion…. [T]his border policy is not only unfair to visitors, but also constitutes an affront to the millions of Americans who are grappling with mental-

What kind of roles should mental health experts play in the development of immigration, gun, or other laws that target people with mental disorders?

Stigmatizing the condition is bad; stigmatizing the treatment is even worse…. Yet this incident will serve only to warn people against seeking treatment for mental illness…. Ms. Richardson, who attempted suicide in 2001 and as a result is paraplegic, has asserted that she has had appropriate treatment, and that she now has a fulfilling, purposeful life. We should applaud people who get treatment and manage to live deeply despite their challenges [and] put to rest the idea that people with mental health conditions who pose no danger are unwelcome in our country.

December 8, 2013, “Opinion: Shameful Profiling of the Mentally Ill” by Andrew Solomon. From the New York Times, 12/8/2013, © 2013 New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

WHAT ARE THE BEHAVIORAL TREATMENTS FOR UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION? Behavioral therapists use a variety of strategies to help increase the number of rewards experienced by their depressed clients (Dimidjian et al., 2014; Martell et al., 2010): (1) First the therapist selects activities that the client considers pleasurable, such as going shopping or taking photos, and encourages the person to set up a weekly schedule for engaging in them. Studies have shown that adding positive activities to a person’s life—

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened.”

Dr. Seuss

These behavioral techniques seem to be of only limited help when just one of them is applied. However, when two or more such techniques are combined, behavioral treatment does appear to reduce depressive symptoms, particularly if the depression is mild. It is worth noting that Lewinsohn himself has combined behavioral techniques with cognitive strategies in recent years in an approach similar to the cognitive-

The Cognitive Model Cognitive theorists believe that people with unipolar depression persistently view events in negative ways and that such perceptions lead to their disorder. The two most influential cognitive explanations are the theory of learned helplessness and the theory of negative thinking.

LEARNED HELPLESSNESS Feelings of helplessness fill this account of a young woman’s depression:

Mary was 25 years old and had just begun her senior year in college…. Asked to recount how her life had been going recently, Mary began to weep. Sobbing, she said that for the last year or so she felt she was losing control of her life and that recent stresses (starting school again, friction with her boyfriend) had left her feeling worthless and frightened. Because of a gradual deterioration in her vision, she was now forced to wear glasses all day. “The glasses make me look terrible,” she said, and “I don’t look people in the eye much any more.” Also, to her dismay, Mary had gained 20 pounds in the past year. She viewed herself as overweight and unattractive. At times she was convinced that with enough money to buy contact lenses and enough time to exercise she could cast off her depression; at other times she believed nothing would help…. Mary saw her life deteriorating in other spheres, as well. She felt overwhelmed by schoolwork and, for the first time in her life, was on academic probation…. In addition to her dissatisfaction with her appearance and her fears about her academic future, Mary complained of a lack of friends. Her social network consisted solely of her boyfriend, with whom she was living. Although there were times she experienced this relationship as almost unbearably frustrating, she felt helpless to change it and was pessimistic about its permanence.

(Spitzer et al., 1983, pp. 122–

learned helplessness The perception, based on past experiences, that one has no control over one’s reinforcements.

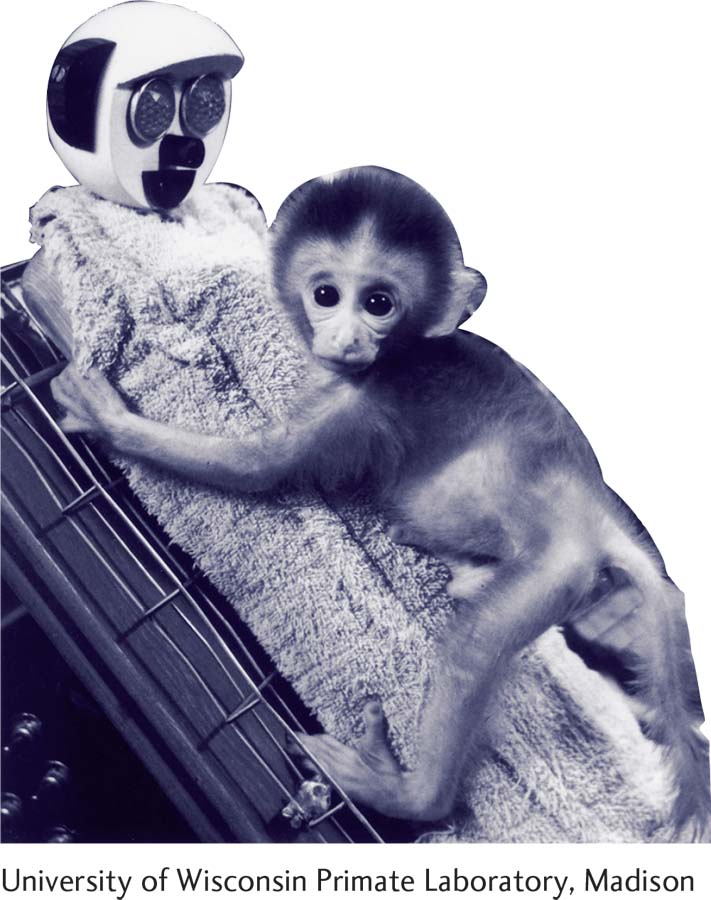

Mary feels that she is “losing control of her life.” According to psychologist Martin Seligman (1975), such feelings of helplessness are at the center of her depression. Since the mid-

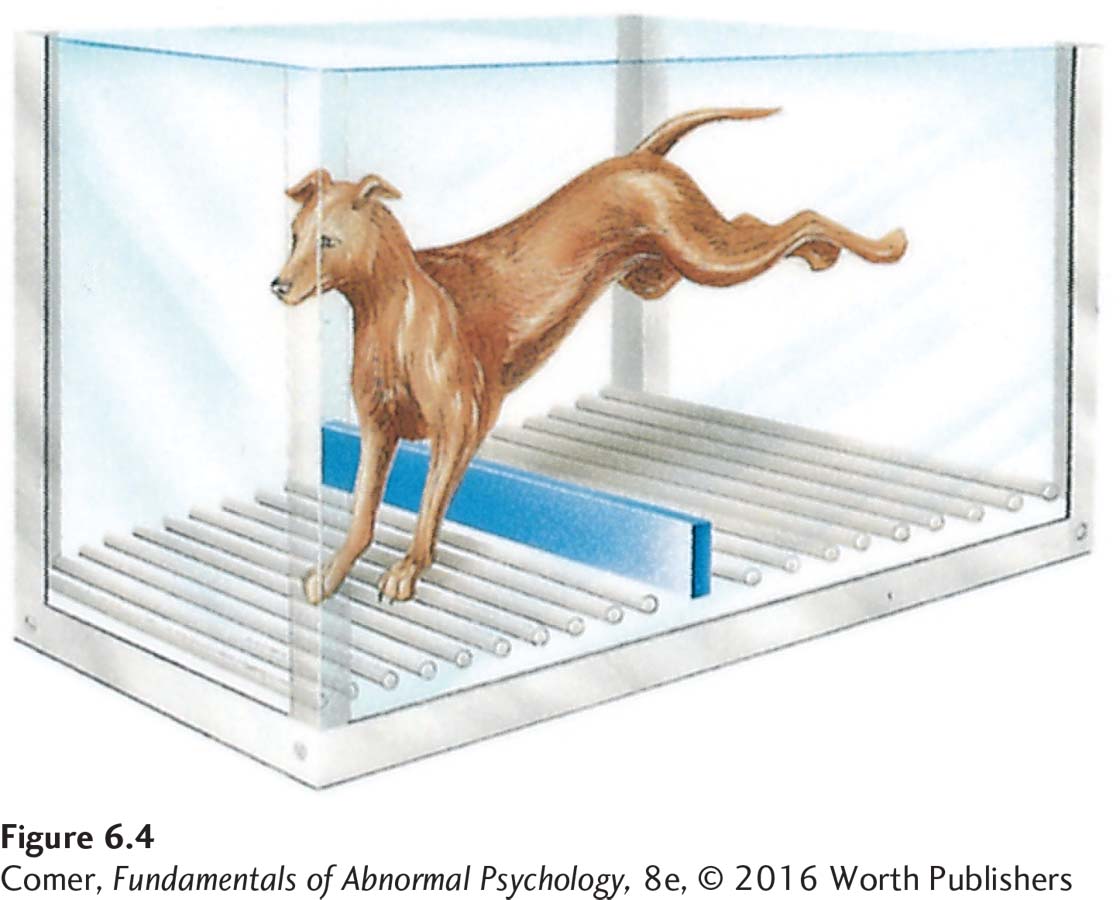

Seligman’s theory first began to take shape when he was working with laboratory dogs. In one procedure, he strapped dogs into an apparatus called a hammock, in which they received shocks periodically no matter what they did. The next day each dog was placed in a shuttle box, a box divided in half by a barrier over which the animal could jump to reach the other side (see Figure 6.4). Seligman applied shocks to the dogs in the box, expecting that they, like other dogs in this situation, would soon learn to escape by jumping over the barrier. However, most of these dogs failed to learn anything in the shuttle box. After a flurry of activity, they simply “lay down and quietly whined” and accepted the shock.

Seligman decided that while receiving inescapable shocks in the hammock the day before, the dogs had learned that they had no control over unpleasant events (shocks) in their lives. That is, they had learned that they were helpless to do anything to change negative situations. Thus, when later they were placed in a new situation (the shuttle box) where they could in fact control their fate, they continued to believe that they were generally helpless. Seligman noted that the effects of learned helplessness greatly resemble the symptoms of human depression, and he proposed that people in fact become depressed after developing a general belief that they have no control over reinforcements in their lives.

In numerous human and animal studies, participants who undergo helplessness training have displayed reactions similar to depressive symptoms (Dygdon & Dienes, 2013). When, for example, human participants are exposed to uncontrollable negative events, they later score higher than other individuals on a depressive mood survey (Miller & Seligman, 1975). Similarly, helplessness-

The learned helplessness explanation of depression has been revised somewhat over the past several decades. According to a newer version of the theory, the attribution-

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Color of Depression

In Western society, black is often the color of choice in describing depression. British prime minister Winston Churchill called his recurrent episodes a “black dog always waiting to bare its teeth.” American novelist Ernest Hemingway referred to his bouts as “black-

Consider a college student whose girlfriend breaks up with him. If he attributes this loss of control to an internal cause that is both global and stable—

Some theorists have refined the helplessness model yet again in recent years. They suggest that attributions are likely to cause depression only when they further produce a sense of hopelessness in a person (Wain et al., 2011). By taking this factor into consideration, clinicians are often able to predict depression with still greater precision (Wang et al., 2013).

Although the learned helplessness theory of unipolar depression has been very influential, it too has imperfections. First, much of the learned helplessness research relies on animal subjects. It is impossible to know whether the animals’ symptoms do in fact reflect the clinical depression found in humans. Second, the attributional feature of the theory raises difficult questions. What about the dogs and rats who learn helplessness? Can animals make attributions, even implicitly?

NEGATIVE THINKING Like Seligman, Aaron Beck believes that negative thinking lies at the heart of depression (Beck & Weishaar, 2014; Beck, 2002, 1991, 1967). According to Beck, maladaptive attitudes, a cognitive triad, errors in thinking, and automatic thoughts combine to produce the clinical syndrome.

One-

cognitive triad The three forms of negative thinking that Aaron Beck theorizes lead people to feel depressed. The triad consists of a negative view of one’s experiences, oneself, and the future.

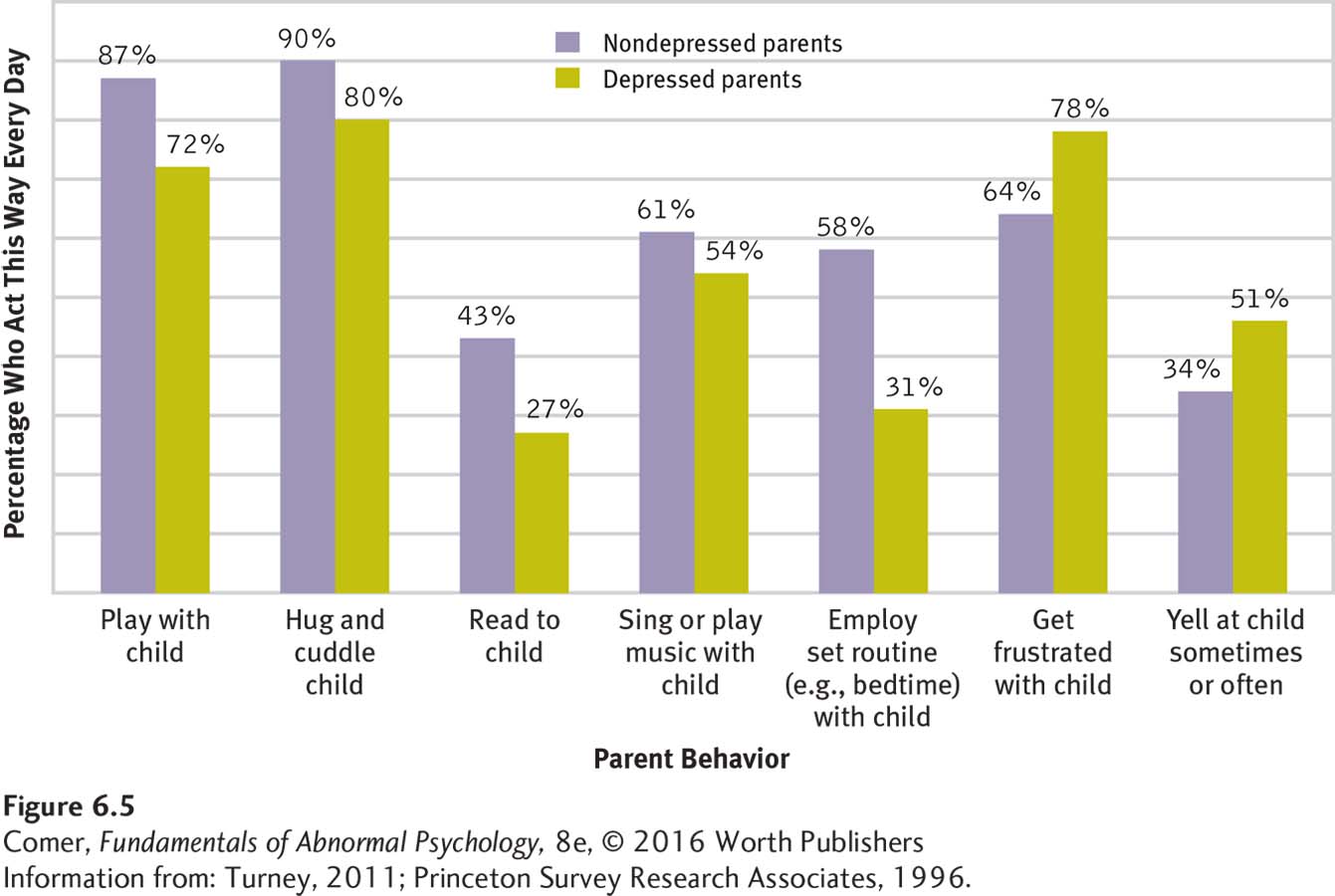

Beck believes that some people develop maladaptive attitudes as children, such as “My general worth is tied to every task I perform” or “If I fail, others will feel repelled by me.” The attitudes result from their early interactions and experiences (see Figure 6.5). Many failures are inevitable in a full, active life, so such attitudes are inaccurate and set the stage for all kinds of negative thoughts and reactions. Beck suggests that later in these people’s lives, upsetting situations may trigger an extended round of negative thinking. That thinking typically takes three forms, which he calls the cognitive triad: the individuals repeatedly interpret (1) their experiences, (2) themselves, and (3) their futures in negative ways that lead them to feel depressed. The cognitive triad is at work in the thinking of this depressed person:

I can’t bear it. I can’t stand the humiliating fact that I’m the only woman in the world who can’t take care of her family, take her place as a real wife and mother, and be respected in her community. When I speak to my young son Billy, I know I can’t let him down, but I feel so ill-

(Fieve, 1975)

According to Beck, depressed people also make errors in their thinking. In one common error of logic, they draw arbitrary inferences—

Finally, depressed people have automatic thoughts, a steady train of unpleasant thoughts that keep suggesting to them that they are inadequate and that their situation is hopeless. Beck labels these thoughts “automatic” because they seem to just happen, as if by reflex. In the course of only a few hours, depressed people may be visited by hundreds of such thoughts: “I’m worthless…. I’ll never amount to anything …. let everyone down…. Everyone hates me…. My responsibilities are overwhelming…. I’ve failed as a parent…. I’m stupid…. Everything is difficult for me…. Things will never change.”

Many studies have produced evidence in support of Beck’s explanation (Pössel & Black, 2014). Several of them confirm that depressed people hold maladaptive attitudes and that the more of these maladaptive attitudes they hold, the more depressed they tend to be (Thomas & Altareb, 2012). Still other research has found the cognitive triad at work in depressed people (Lai et al., 2014). And still other studies have supported Beck’s claims about errors in logic (Alcalar et al., 2012). In one study, female participants—

Finally, research has supported Beck’s claim that automatic thoughts are tied to depression (Alcalar et al., 2012). In several classic studies, nondepressed participants who are tricked into reading negative automatic-

cognitive therapy A therapy developed by Aaron Beck that helps people identify and change the maladaptive assumptions and ways of thinking that help cause their psychological disorders.

WHAT ARE THE COGNITIVE TREATMENTS FOR UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION? To help clients overcome this negative thinking, Beck has developed a treatment approach that he calls cognitive therapy (Beck & Weishaar, 2014). However, as you will see, the approach also includes a number of behavioral techniques, particularly as therapists try to get clients moving again and encourage them to try out new behaviors. Thus, many theorists consider this approach a cognitive-

PHASE 1: Increasing activities and elevating mood Using behavioral techniques to set the stage for cognitive treatment, therapists first encourage clients to become more active and confident. Clients spend time during each session preparing a detailed schedule of hourly activities for the coming week. As they become more active from week to week, their mood is expected to improve.

PHASE 2: Challenging automatic thoughts Once people are more active and feeling some emotional relief, cognitive therapists begin to educate them about their negative automatic thoughts. The individuals are instructed to recognize and record automatic thoughts as they occur and to bring their lists to each session. Therapist and client then test the reality behind the thoughts, often concluding that they are groundless.

PHASE 3: Identifying negative thinking and biases As people begin to recognize the flaws in their automatic thoughts, cognitive therapists show them how illogical thinking processes are contributing to these thoughts. The therapists also guide clients to recognize that almost all their interpretations of events have a negative bias and to change that style of interpretation.

PHASE 4: Changing primary attitudes Therapists help clients change the maladaptive attitudes that set the stage for their depression in the first place. As part of the process, therapists often encourage clients to test their attitudes, as in the following therapy discussion:

| Therapist: | On what do you base this belief that you can’t be happy without a man? |

| Patient: | I was really depressed for a year and a half when I didn’t have a man. |

| Therapist: | Is there another reason why you were depressed? |

| Patient: | As we discussed, I was looking at everything in a distorted way. But I still don’t know if I could be happy if no one was interested in me. |

| Therapist: | I don’t know either. Is there a way we could find out? |

| Patient: | Well, as an experiment, I could not go out on dates for a while and see how I feel. |

| Therapist: | I think that’s a good idea. Although it has its flaws, the experimental method is still the best way currently available to discover the facts. You’re fortunate in being able to run this type of experiment. Now, for the first time in your adult life you aren’t attached to a man. If you find you can be happy without a man, this will greatly strengthen you and also make your future relationships all the better. |

(Beck et al., 1979, pp. 253–

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.”

Eleanor Roosevelt

Over the past several decades, hundreds of studies have shown that Beck’s therapy and similar cognitive and cognitive-

It is worth noting that a growing number of today’s cognitive-

The Sociocultural Model of Unipolar Depression

Sociocultural theorists propose that unipolar depression is strongly influenced by the social context that surrounds people. Their belief is supported by the finding, discussed earlier, that depression is often triggered by outside stressors. Once again, there are two kinds of sociocultural views—

Why might problems in the social arena—

The Family-

Researchers have also found that people whose lives are isolated and without intimacy are particularly likely to become depressed at times of stress (Hölzel et al., 2011; Nezlek et al., 2000). Some highly publicized studies conducted in England several decades ago showed that women who had three or more young children, lacked a close confidante, and had no outside employment were more likely than other women to become depressed after going through stressful events (Brown, 2002; Brown & Harris, 1978). Studies have also found that depressed people who lack social support remain depressed longer than those who have a supportive spouse or warm friendships.

Family-

interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) A treatment for unipolar depression that is based on the belief that clarifying and changing one’s interpersonal problems helps lead to recovery.

INTERPERSONAL PSYCHOTHERAPY Developed by clinical researchers Gerald Klerman and Myrna Weissman, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) holds that various interpersonal situations may lead to depression and must be addressed. Particularly problematic are interpersonal loss, interpersonal role dispute, interpersonal role transition, and interpersonal deficits (Bleiberg & Markowitz, 2014; Verdeli, 2014). Over the course of around 16 sessions, IPT therapists address these areas.

First, depressed people may, as psychodynamic theorists suggest, be having a grief reaction over an important interpersonal loss, the loss of a loved one. In such cases, IPT therapists encourage clients to look closely at their relationship with the lost person and express any feelings of anger they may discover. Eventually clients develop new ways of remembering the lost person and also look for new relationships.

Second, depressed people may find themselves in the midst of an interpersonal role dispute. Role disputes occur when two people have different expectations of their relationship and of the role each should play. IPT therapists help clients examine whatever role disputes they may be involved in and then develop ways of resolving them.

Depressed people may also be going through an interpersonal role transition, brought about by major life changes such as divorce or the birth of a child. They may feel overwhelmed by the role changes that accompany the life change. In such cases, IPT therapists help them develop the social supports and skills the new roles require.

Finally, some depressed people display interpersonal deficits, such as extreme shyness or social awkwardness, that prevent them from having intimate relationships (see MindTech below). IPT therapists may help such clients identify their deficits and teach them social skills and assertiveness in order to improve their social effectiveness. In the following discussion, the therapist encourages a depressed man to recognize the effect his behavior has on others:

| Client: | (After a long pause with eyes downcast, a sad facial expression, and slumped posture) People always make fun of me. I guess I’m just the type of guy who really was meant to be a loner, damn it. (Deep sigh) |

| Therapist: | Could you do that again for me? |

| Client: | What? |

| Therapist: | The sigh, only a bit deeper. |

| Client: | Why? (Pause) Okay, but I don’t see what ….kay. (Client sighs again and smiles) |

| Therapist: | Well, that time you smiled, but mostly when you sigh and look so sad I get the feeling that I better leave you alone in your misery, that I should walk on eggshells and not get too chummy or I might hurt you even more. |

| Client: | (A bit of anger in his voice) Well, excuse me! I was only trying to tell you how I felt. |

| Therapist: | I know you felt miserable, but I also got the message that you wanted to keep me at a distance, that I had no way to reach you. |

| Client: | (Slowly) I feel like a loner, I feel that even you don’t care about me— |

| Therapist: | I wonder if other folks need to pass this test, too? |

(Beier & Young, 1984, p. 270)

Studies suggest that IPT and related interpersonal treatments for depression have a success rate similar to that of cognitive and cognitive-

MindTech

Texting: A Relationship Buster?

Texting: A Relationship Buster?

Can you think of ways in which texting might sometimes be helpful to relationships and communications?

Texting has now become the leading way that most people communicate with others (Pew Research Center, 2015; Cocotas, 2013). The average 18-

Based on her studies, MIT professor Sherry Turkle (2013, 2012) has concluded that communicating primarily via text does indeed affect relationships negatively. Many of her participants reported, “I’d rather text than talk.” Turkle concludes from her research that people often use texting as a crutch to avoid direct communication and possible confrontations. Moreover, her participants said that texting saves valuable time over face-

In related work, researcher Karla Klein Murdock (2013) interviewed 83 college freshmen about their daily texting habits, along with their levels of social and personal stress, sleep patterns, and happiness. She found that hastily written texts (which is to say, most texts) often lend themselves to misunderstandings between senders and receivers—

None of this suggests that texting per se is a detriment to social or personal happiness. Rather, it seems to be the exclusive and excessive use of it that is the problem. It just may be that many important discussions are better served by in-

couple therapy A therapy format in which the therapist works with two people who share a long-

COUPLE THERAPY As you have read, depression can result from marital discord, and recovery from depression is often slower for people who do not receive support from their spouse (Park & Unützer, 2014). In fact, as many as half of all depressed clients may be in a dysfunctional relationship. Thus many cases of depression have been treated by couple therapy, the approach in which a therapist works with two people who share a long-

Therapists who offer integrative behavioral couples therapy teach specific communication and problem-

The Multicultural Perspective Two issues have captured the interest of multicultural theorists: (1) links between gender and depression and (2) ties between cultural and ethnic background and depression.

GENDER AND DEPRESSION As you have read, there is a strong link between gender and depression. Women in places as far apart as France, Sweden, Lebanon, New Zealand, and the United States are at least twice as likely as men to receive a diagnosis of unipolar depression (Schuch et al., 2014). Why the huge difference between the sexes? A variety of theories have been offered.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Paternal Postpartum Depression

Considerable research has already indicated that a mother’s postpartum depression can lead to disturbances in a child’s social, behavioral, and cognitive development. Research suggests that a father’s postpartum depression can have similar effects (Koh et al., 2014; Edoka et al., 2011).

The artifact theory holds that women and men are equally prone to depression but that clinicians often fail to detect depression in men (Emmons, 2010). Perhaps depressed women display more emotional symptoms, such as sadness and crying, which are easily diagnosed, while depressed men mask their depression behind traditionally “masculine” symptoms such as anger. Although a popular explanation, this view has failed to receive consistent research support. It turns out that women are actually no more willing or able than men to identify their depressive symptoms and to seek treatment (McSweeney, 2004; Nolen-

The hormone explanation holds that hormone changes trigger depression in many women (Kurita et al., 2013). A woman’s biological life from her early teens to middle age is marked by frequent changes in hormone levels. Gender differences in rates of depression also span these same years. Research suggests, however, that hormone changes alone are not responsible for the high levels of depression in women (Whiffen & Demidenko, 2006). Important social and life events that occur at puberty, pregnancy, and menopause could likewise have an effect. Hormone explanations have also been criticized as sexist, since they imply that a woman’s normal biology is flawed (see PsychWatch below).

The life stress theory suggests that women in our society are subject to more stress than men (Astbury, 2010). On average they face more poverty, more menial jobs, less adequate housing, and more discrimination than men—

The body dissatisfaction explanation states that females in Western society are taught, almost from birth, to seek a low body weight and slender body shape—

PsychWatch

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Déjà Vu All Over Again

Back in the early 1990s, one of the biggest controversies in the development of DSM-

This recommendation set off an uproar. Many clinicians (including some dissenting members of the work group), several national organizations, interest groups, and the media warned that this diagnostic category would “pathologize” severe cases of premenstrual syndrome, or PMS, the premenstrual discomforts that are common and normal, and might cause women’s behavior in general to be attributed largely to “raging hormones” (a stereotype that society was finally rejecting). They argued that data were lacking to include the new category (Chase, 1993; DeAngelis, 1993).

The solution? A compromise. PMDD was not listed as a formal category in DSM-

The lack-

A final explanation for the gender differences found in depression is the rumination theory. As you read earlier, rumination is the tendency to keep focusing on one’s feelings when depressed and to consider repeatedly the causes and consequences of that depression (“Why am I so down? …. won’t be able to finish my work if I keep going like this….”). It turns out that women are more likely than men to ruminate when their mood darkens, perhaps making them more vulnerable to the onset of clinical depression (Johnson & Whisman, 2013; Nolen-

Each of these explanations for the gender difference in unipolar depression offers food for thought. Each has gathered just enough supporting evidence to make it interesting and just enough evidence to the contrary to raise questions about its usefulness. Thus, at present, the gender difference in depression remains one of the most talked-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Parental Impact

It has been estimated that 400,000 infants are born each year to depressed mothers (Murray & Nyp, 2011).

CULTURAL BACKGROUND AND DEPRESSION Depression is a worldwide phenomenon, and certain symptoms of this disorder seem to be constant across all countries. A landmark study of four countries—

BETWEEN THE LINES

World Count

More than 350 million people suffer from depression worldwide (World Health Organization, 2012).

Within the United States, researchers have found few differences in the symptoms of depression among members of different ethnic or racial groups. Nor have they found significant differences in the overall rates of depression between such minority groups. On the other hand, recent research has revealed that there are often striking differences between ethnic/racial groups in the recurrence of depression. Hispanic Americans and African Americans are 50 percent more likely than white Americans to have recurrent episodes of depression (González et al., 2010). Why this difference? Around 54 percent of depressed white Americans receive treatment for their disorders (medication and/or psychotherapy), compared with 34 percent of depressed Hispanic Americans and 40 percent of depressed African Americans (González et al., 2010). It may be that minority groups in the United States are more vulnerable to repeated experiences of depression partly because many of their members have more limited treatment opportunities when they are depressed.

Research has also revealed that depression is distributed unevenly within some minority groups. This is not totally surprising, given that each minority group itself consists of people of varied backgrounds and cultural values. For example, depression is more common among Hispanic and African Americans born in the United States than among Hispanic and African American immigrants (González et al., 2010; Miranda et al., 2005). Moreover, within the Hispanic American population, Puerto Ricans have a higher rate of depression than do Mexican Americans or Cuban Americans.

Do you think culture-

Multicultural Treatments In Chapter 2, you read that culture-

In the treatment of unipolar depression, culture-

Summing Up

UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION: THE DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS People with unipolar depression, the most common pattern of mood disorder, suffer from depression only. The various disorders characterized by unipolar depression are called depressive disorders in DSM-

According to the biological view, low activity of two neurotransmitters, norepinephrine and serotonin, helps cause depression. Hormonal factors may also be at work. So, too, may deficiencies of key proteins and other chemicals within certain neurons. Brain-

According to the psychodynamic view, certain people who experience real or imagined losses may regress to an earlier stage of development, fuse with the person they have lost, and eventually become depressed. Psychodynamic therapists try to help persons with unipolar depression recognize and work through their losses and excessive dependence on others.

The behavioral view says that when people experience a large reduction in their positive rewards in life, they become more and more likely to become depressed. Behavioral therapists try to reintroduce clients to activities that they once found pleasurable, reward nondepressive behaviors, and teach effective social skills.

The leading cognitive views focus on learned helplessness and negative thinking. According to Seligman’s learned helplessness theory, people become depressed when they believe that they have lost control over the reinforcements in their lives and when they attribute this loss to causes that are internal, global, and stable. According to Beck’s theory of negative thinking, maladaptive attitudes, the cognitive triad, errors in thinking, and automatic thoughts help produce unipolar depression. Cognitive therapists help depressed persons identify and change their dysfunctional cognitions, and cognitive-

Sociocultural theories propose that unipolar depression is influenced by social and cultural factors. Family-