Solving the Great Economic Problem

Markets around the world are linked to one another. A change in supply or demand in one market can influence markets for entirely different products thousands of miles away. But what does all this linking accomplish? The great economic problem is to arrange our limited resources to satisfy as many of our wants as possible. Let’s imagine that war in the Middle East reduces the supply of oil. We must economize on oil. But how? It would be foolish to reduce oil equally in all uses—oil is more valuable in some uses than in others. We want to shift oil out of low-valued uses, where we can do without or where good substitutes for oil exist, so that we can keep supplying oil for high-valued uses, where oil has few good substitutes.

The great economic problem is to arrange our limited resources to satisfy as many of our wants as possible.

One way to make this shift would be for a central planner to issue orders. The central planner would order so much oil to be used in the steel industry, so much for heating, and so much for Sunday driving. But how would the central planner know the value of oil in each of its millions of uses? No one knows for certain all the uses of oil, let alone which uses of oil are high-valued uses and which are low-valued uses. Is the oil used to produce steel more valuable than the oil used to produce vegetables? Even if steel is worth more than vegetables, the answer isn’t obvious because electricity might be a good substitute for oil in producing steel but not for producing vegetables. To estimate the value of oil in different uses, therefore, the central planner would have to gather information about all the uses of oil and all of the substitutes for oil in each use (and all of the substitutes for the substitutes!). Using this information, the central planner would then have to somehow compute the optimal allocation of oil and then send out thousands of orders directing oil to its many uses in the economy.

The task of central planning is impossibly complex and we haven’t yet discussed incentives. Why would anyone have an incentive to send truthful information to the central planner? Each user of oil would surely announce that their use is the high-valued use for which no substitute is possible. And what incentive would the central planner have to actually direct oil to its high-value uses?

The U.S. government briefly tried to centrally plan the allocation of oil during the 1973–1974 oil crisis. President Nixon even went so far as to forbid gas stations from opening on Sundays in an attempt to reduce Sunday driving! We describe the consequences of this approach to the oil crisis at greater length in the next chapter. The Soviet Union and China went much further than the United States and tried to centrally plan entire economies. Central planning on a large scale, however, failed and has now been abandoned throughout virtually all the world (Cuba and North Korea, both very poor countries, are the exceptions).

The central planning approach failed because of problems of information and incentives. We need a better approach.

Users of oil have a lot of information about the value of oil in their own uses, much more information than could ever be communicated to a central planner. We need to take advantage of this information without attempting to communicate it to a central bureaucracy. Ideally, each user of oil would compare the value of oil in their use with the value of oil in alternative uses, and each user of oil would have an incentive to give up the oil if it has a lower value in their use than in alternative uses. This is exactly what the price system accomplishes.

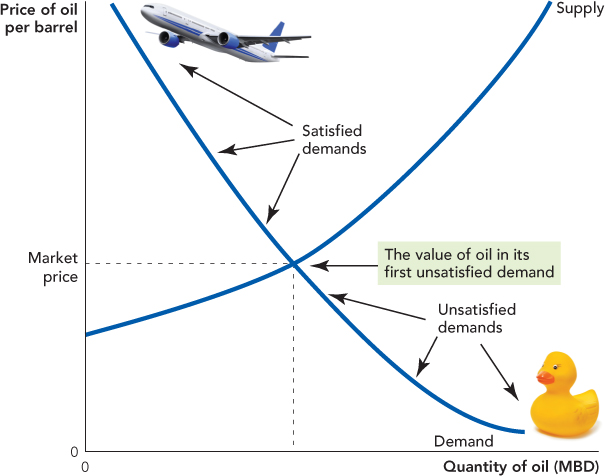

Let’s go back to the person thinking about whether to pave the driveway with asphalt or brick. This person knows the value of a paved driveway but doesn’t know what uses the asphalt has elsewhere in the economy. He or she does know the price of asphalt, and in a free market, the price of asphalt is equal to the value of the asphalt in its next highest-value use. Take a look at Figure 7.1, which is just the now-familiar supply and demand diagram. Remember that the value of a good in its various uses is given by the height of the demand curve. Notice that the equilibrium price splits the uses of the good into two—above the equilibrium price are the high-value, satisfied demands; below the price are the low-value, unsatisfied demands. Now what is the value of the highest-value demand that is not satisfied? It’s just equal to the market price (or if you like, “just below” the market price). In other words, if one more barrel of oil became available, the highest-value use of that barrel would be to satisfy the first presently unsatisfied demand. The market price tells us the value of the good in its next highest-valued use.

FIGURE 7.1

It is part of the marvel of a free market that, under the right conditions, the money price of the motorcycle exactly represents the value of the resources that went into producing the motorcycle, namely the value those resources would have had in their next highest-valued use.

DON NICHOLS/E+/GETTY IMAGES

When a consumer compares the price of asphalt to the value of asphalt for paving his driveway, he is comparing the value of asphalt on his driveway to its opportunity cost. And remember, because markets are linked, the price of asphalt is linked to the price of oil, and the price of oil is linked to the demand for automobiles in China and the supply of ethanol and the price of sugar…. So when the consumer compares the value of asphalt in paving his driveway to the price of asphalt, he may be comparing the value of asphalt in paving his driveway to the value of 500 gallons of gasoline used by a motorist in Brazil. Or, in other words, when you decide whether to drive to school or take the bus, you are deciding whether your use of oil is more valuable than the billions of other uses of oil in the world that are presently unsatisfied!

The market solves the information problem by collapsing all the relevant information in the world about the uses of oil into a single number, the price. As Nobel laureate Friedrich Hayek wrote:*

The most significant fact about this system is the economy of knowledge with which it operates … by a kind of symbol [the price], only the most essential information is passed on and passed on only to those concerned…. The marvel is that in a case like that of a scarcity of one raw material, without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation, are made to use the material or its products more sparingly; i.e., they move in the right direction.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 7.3

Peanuts are used primarily for food dishes, but they are also used in bird feed, paint, varnish, furniture polish, insecticides, and soap. Rank these uses from higher to lower value taking into account in which use the peanuts are critical and in which uses there are good substitutes. Don’t obsess over this: We know you are not a peanut expert, but see if you can come up with a sense of higher and lower values.

Peanuts are used primarily for food dishes, but they are also used in bird feed, paint, varnish, furniture polish, insecticides, and soap. Rank these uses from higher to lower value taking into account in which use the peanuts are critical and in which uses there are good substitutes. Don’t obsess over this: We know you are not a peanut expert, but see if you can come up with a sense of higher and lower values.

Question 7.4

Imagine that there is a large peanut crop failure in China, which produces more than one-third of the world’s supply. Which of the uses that you ranked in the previous question will be cut back?

Imagine that there is a large peanut crop failure in China, which produces more than one-third of the world’s supply. Which of the uses that you ranked in the previous question will be cut back?

In addition to solving the information problem, the price system also solves the incentive problem. It’s in a consumer’s interest to pay attention to prices! When the price of an oil product like asphalt increases, consumers have an incentive to turn to substitutes like bricks and, in so doing, they free up oil to be used elsewhere in the economy where it is of higher value.

The worldwide market accomplishes this immense task of allocating resources without any central planning or control. No one knows or understands all the links between oil, sugar, and brick driveways, but the links are there and the market works even without anyone’s understanding or knowledge. Amazed by what he saw, Adam Smith said the market works as if “an invisible hand” guided the process.

Nobel laureate Vernon Smith, whom we met in Chapter 4, put it this way:

At the heart of economics is a scientific mystery: How is it that the pricing system accomplishes the world’s work without anyone being in charge? Like language, no one invented it. None of us could have invented it, and its operation depends in no way on anyone’s comprehension or understanding of it…. The pricing system—How is order produced from freedom of choice?—is a scientific mystery as deep, fundamental and inspiring as that of the expanding universe or the forces that bind matter.8