REGION

10.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe the historical and contemporary regional patterns of urbanization, and the models geographers use to understand cities.

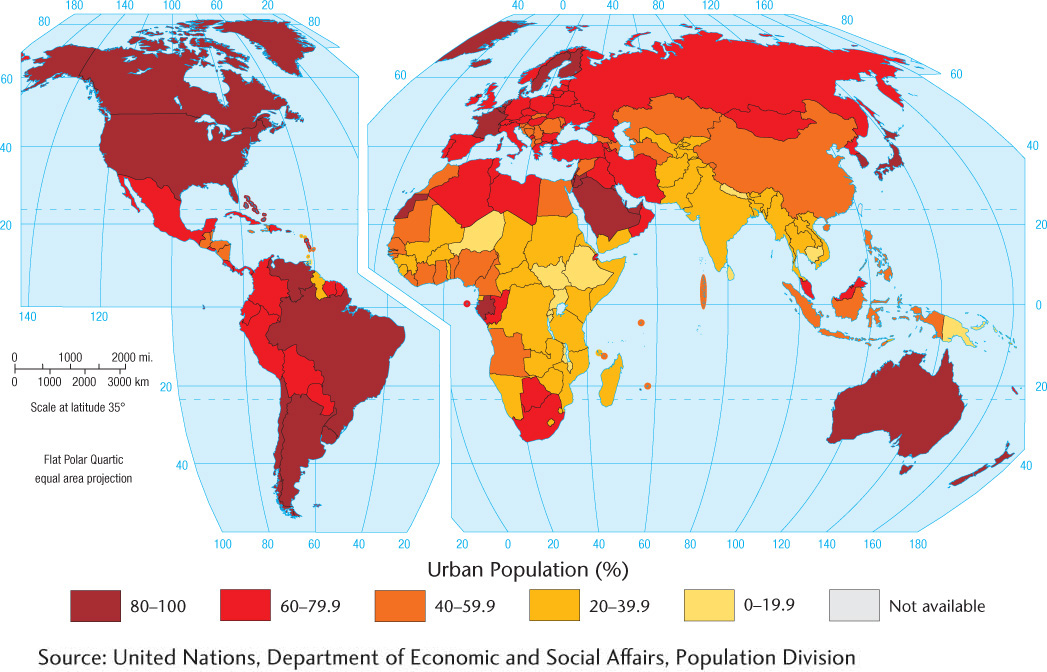

We all know from our own travels, locally or internationally, that some regions contain lots of cities, while others contain relatively few, and that the size, population density, and look and feel of those cities can vary greatly. How then can we begin to understand the location, distribution, and size of cities? We start with a consideration of global patterns of urbanization, examining the general distribution of urban populations around the world. A quick look at Figure 10.2 reveals differing patterns of urbanized population—the percentage of a nation’s population living in towns and

urbanized population

The proportion of a country’s population living in cities.

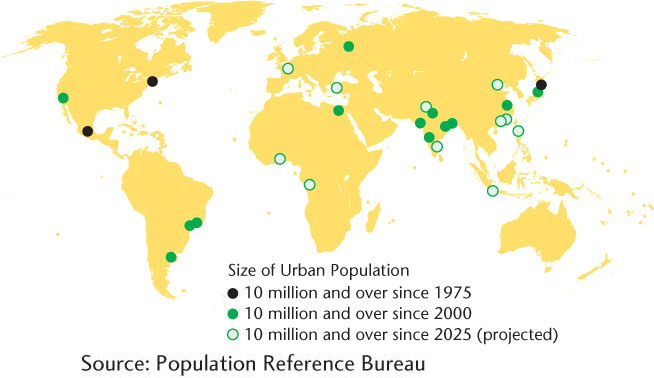

PATTERNS AND PROCESSES OF URBANIZATION

According to United Nations estimates, almost all the worldwide population growth in the next several decades will be concentrated in urban areas, with the cities of the less developed regions accounting for most of that increase (Figure 10.3). The reasons for this urban population growth and its uneven distribution around the world vary, as each country’s unique history and society present a slightly different narrative of urban and economic development. Making matters more complex is the lack of a standard definition of what constitutes a city. Consequently, the criteria used to calculate a country’s urbanized population differ from nation to nation. Using data based on these varying criteria would result in misleading conclusions. For example, the Indian government defines an urban center as an area having 5000 inhabitants, with an adult male population employed predominantly in nonagricultural work. In contrast, the U.S. Census Bureau defines a city as a densely populated area of 2500 people or more, and South Africa counts as a city any settlement of 500 or more people. It is important to remember, then, that an international comparison of urbanized population data can be made only by taking into account the varying definitions of a city.

415

416

Urban growth comes from two sources: the migration of people from rural areas to cities (see also the section on mobility) and the higher natural birth rates of these recent migrants (see Chapter 3). People move to the cities for a variety of reasons, most of which relate to the effects of uneven economic development in their country (see Chapter 9). Cities are often the centers of economic growth, whereas opportunities for land ownership and/or farming-based jobs are, in many countries, rare. Because urban employment is unreliable, many migrants continue to have large numbers of children to construct a more extensive family support system. Having a larger family increases the chance that someone in the household will get work. The demographic transition to smaller families comes later, when a certain degree of security is ensured. Often, this transition occurs as women enter the workforce (see Chapter 3).

A BRIEF HISTORY OF URBANIZATION

Humans have not always lived in cities. Indeed, for most of our existence we humans have lived in small, nomadic groups of 25 to 50 hunter-gatherers. Such groups eventually became sedentary and formed into small villages, but these were nothing like what you would recognize as a real city today.

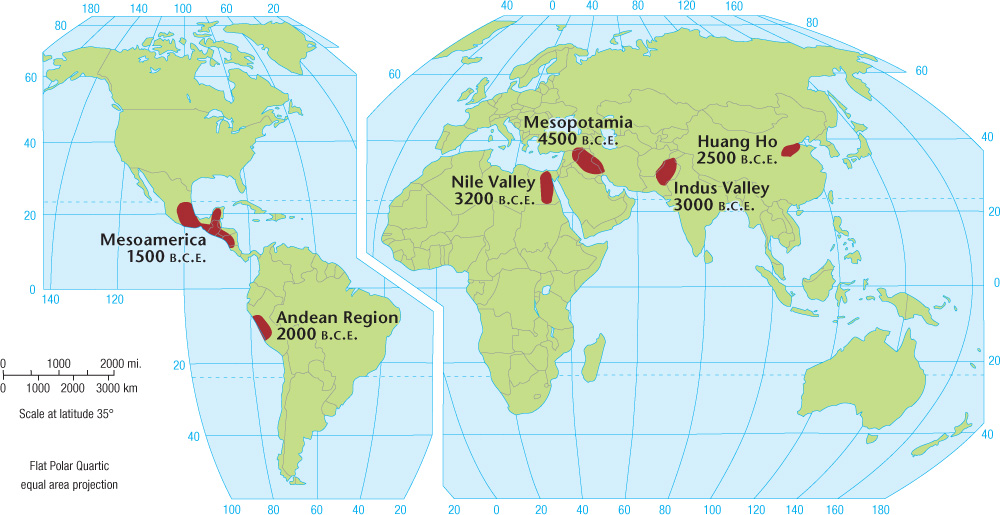

In the Middle East, where the first cities appeared, a network of permanent agricultural villages developed about 10,000 years ago. These farming villages were modest in size, rarely with more than 200 people, and were probably organized on a kinship basis.

Although small farming villages predate cities, it is wrong to assume that a simple quantitative change took place whereby villages slowly grew, first into towns and then into cities. Neolithic settlements that date from around 9000 b.c.e. (Jericho, in the modern-day Palestinian territories on the West Bank) and 7500 b.c.e. (Çatalhöyük, in modern-day Turkey) are considered by some archaeologists to be the earliest real cities (Figure 10.4). Others do not believe they qualified as true cities, based on their small populations and lack of apparent social stratification.

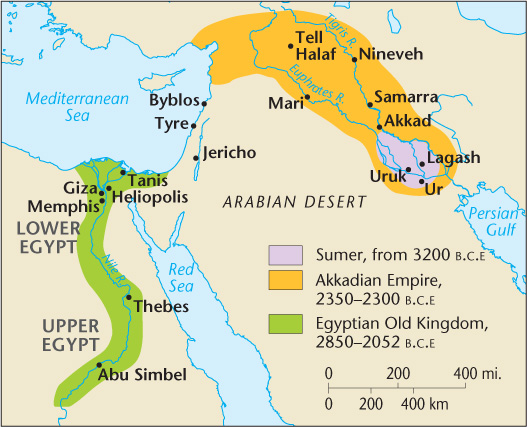

Urban settlements dating to around 4000 b.c.e. in Mesopotamia (the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq) were without doubt true cities (Figure 10.5). Small by current standards, Mesopotamian cities covered 0.5 to 2 square miles (1.3 to 5 square kilometers), with populations that rarely exceeded 30,000. Nevertheless, the densities within these cities could easily reach 10,000 people per square mile (4000 per square kilometer), which is comparable to the densities in many contemporary cities.

By that time, agricultural technologies in Southwest Asia permitted larger settlements. True cities, then and now, differ qualitatively from agricultural villages. All the inhabitants of agricultural villages were involved in some way in food procurement—tending the agricultural fields or harvesting and preparing the crops. Cities, however, were more removed, both physically and psychologically, from everyday agricultural activities. Food was supplied to the city, but not all city dwellers were involved in obtaining it.

417

Two elements were necessary for this dramatic social change: the creation of an agricultural surplus and the development of a stratified social system. Surplus food, which is a food supply larger than the everyday needs of the agricultural labor force, is a prerequisite for supporting nonfarmers—people who work at administrative, religious, military, or handicraft tasks. Social stratification, understood as the existence of distinct socioeconomic classes, facilitates the collection, storage, and distribution of resources through well-defined channels of authority that can exercise control over goods and people. A society with these two elements—surplus food and a means of storing and distributing it—was prepared for urbanization.

agricultural surplus

The amount of food grown by a society that exceeds the demands of its population.

MODELS FOR THE RISE OF CITIES

One way to understand the transition from village to city life is to model the development of urban life assuming that a single factor is the trigger behind the transition. The question that scholars ask is: “What activity could be so important to an agricultural society that its people would be willing to give some of their surplus to support a social class that specializes in that activity?”

The hydraulic civilization model, developed by Karl Wittfogel, assumes that the development of large-scale irrigation systems was the primary driver of urbanization and that a class of technical specialists were the first urban dwellers. Irrigating agricultural crops yielded more food, and this surplus supported the development of a large nonfarming population. A strong, centralized government backed by an urban-based military could expand its power into the surrounding areas. Farmers who resisted the new authority were denied water. Continued reinforcement of the power elite derived from the need for organizational coordination to ensure continued operation of the irrigation system. Labor specialization developed. Some people farmed; others worked on the irrigation system. Still others became artisans, creating the implements needed to maintain the system, or administrative workers in the direct employ of the power elite’s court.

hydraulic civilization

A civilization based on large-scale irrigation.

Although the hydraulic civilization model fits several areas where cities first arose—China, Egypt, and Mesopotamia—it cannot be applied to all urban hearths. In parts of Mesoamerica, for example, an urban civilization blossomed without widespread irrigated agriculture and therefore without a class of technical experts.

URBAN HEARTH AREAS

The first cities appeared in distinct regions, such as Mesopotamia, the Nile River valley, Pakistan’s Indus River valley, the Yellow River valley of China, Mesoamerica, and the Andean highlands and coastal areas of Peru. These are called urban hearth areas (Figure 10.6).

urban hearth areas

Regions in which the world’s first cities evolved.

418

Scholars have referred to these first cities in Mesopotamia and elsewhere as cosmomagical cities, cities that are arranged spatially according to religious principles. The spatial layouts of cosmomagical cities are similar in three important ways. First, great importance was given to the city’s symbolic center, which was also believed to be the center of the known world. It was therefore the most sacred spot and was frequently identified by a vertical structure of monumental scale that represented the point on Earth closest to the heavens. This symbolic center, or axis mundi, took the form of the ziggurat (a massive structure having the form of a terraced step pyramid with receding levels) in Mesopotamia, the palace or temple in China, and the pyramid in Mesoamerica. Often this elevated structure, which usually served a religious purpose, was close to the palace or seat of political power and to the granary (a storehouse for grain). These three structures were often walled off from the rest of the city, forming a symbolic center that both reflected the significance of these societal functions and dominated the city physically and spiritually. The Forbidden City in Beijing remains one of the best examples of this guarded, fortress-like “city within the city” (Figure 10.7). The second spatial characteristic common to cosmomagical cities is that they were oriented toward the four cardinal directions. By aligning the city in the north-south and east-west directions, the geometric form of the city reflected the order of the universe. It was thought that this alignment would ensure harmony and order over the known world, which was bounded by the city walls.

cosmomagical cities

Types of cities that are arranged spatially according to religious principles; characteristic of very early cities.

axis mundi

The symbolic center of cosmomagical cities, often demarcated by a large vertical structure.

In all these early cities, one sees evidence of a third spatial characteristic: an attempt to shape the form of the city according to that of the universe. The ordering of the space of the city was believed to be essential to maintaining harmony between the human and spiritual worlds. In this way, the world of humans would symbolically replicate the world of the gods. This characteristic may have taken a literal form—a city laid out, for example, in a pattern of a major star constellation. Far more common, however, were cities that symbolically approximated mythical conceptions of the universe. Angkor Thom was an early city in Cambodia that presents one of the best examples of this parallelism. An urban cluster that spread over 6 square miles (15.5 square kilometers), Angkor Thom was a representation in stone of a series of religious beliefs about the nature of the universe. Thus, the city was a microcosmos, a re-creation on Earth of an image of the larger universe.

419

IMPERIALISM AND URBANIZATION

Although urban life originated at several specific places in the world, cities are now found everywhere. How did city life come to these regions? There are two possible explanations. Cities could have evolved spontaneously in different places across the globe, as populations developed new agricultural technologies allowing for a surplus, and their societies differentiated. Or, contact with city dwellers, whether through trade, trans-oceanic voyages, or conquest, could have diffused the techniques and ideas associated with urban dwelling to other areas.

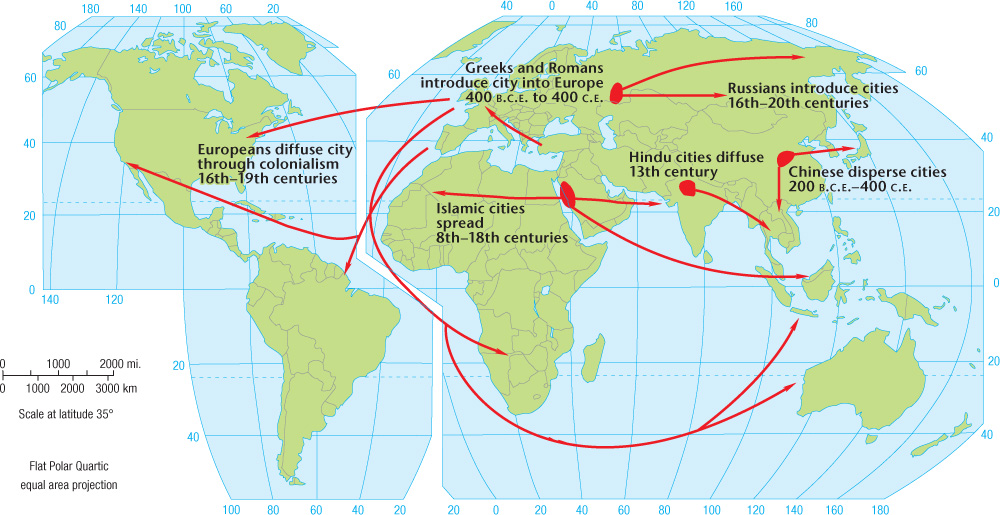

Cities and Conquest There is little doubt that diffusion has been responsible for the dispersal of the city in historical times (Figure 10.8), because the city has commonly been used as a means for imperial expansion. Typically, urban life is carried outward in waves of conquest as the borders of an empire expand. Initially, the military controls newly won lands and sets up collection points for local resources, which are then shipped back to the heart of the empire. As the surrounding countryside is increasingly pacified, the new collection points lose some of their military atmosphere and begin to show the social diversity of a city. Artisans, merchants, and bureaucrats increase in number; families appear; the native people are slowly assimilated into the settlement as workers and may eventually control the city. Finally, the process repeats itself as the empire pushes farther outward: with first a military camp, next a collection point for resources, then a full-fledged city expressing a true division of labor and social diversity.

420

Such a process, however, did not always proceed without opposition. The imposition of a foreign civilization on native peoples was often met with resistance, both physical and symbolic. Expanding urban centers relied on the surrounding countryside for support. Their food was supplied by farmers living fairly close to the city walls, and tribute was demanded from the agricultural peoples living on the edges of the urban world. The increasing needs of the city required more and more land from which to draw resources. However, the peasants farming that land may not have wanted to change their way of life to accommodate the city. The fierce resistance of many Native American groups to the spread of Western urbanization is testimony to the potential power of indigenous society to defy urbanization, although the destructive long-term effects of this kind of resistance suggest that the organized military efforts of urban society were difficult to overcome.

Ancient Empires and Imperial Expansion The ancient Greek civilization, to which both Western civilization and the Western city trace their roots, expanded in part through spreading cities throughout the Mediterranean. Greek imperial cities reached as far as the north shore of Africa, Spain, southern France, and Italy. These cities were of modest size, rarely containing more than 5000 inhabitants. Athens, however, may have reached a population of 300,000 in the fifth century b.c.e.

The Roman civilization supplanted ancient Greece, and was itself centered on a city: Rome. The Romans adopted many urban traits from the Greeks as well as the Etruscans, a civilization of central Italy that Rome had conquered. As the Roman Empire expanded, city life diffused farther into France, while also reaching Germany, England, interior Spain, the Alpine countries, and parts of eastern Europe—areas that had not previously experienced urbanization. Most of these cities were, initially, military and trading outposts of the Roman Empire.

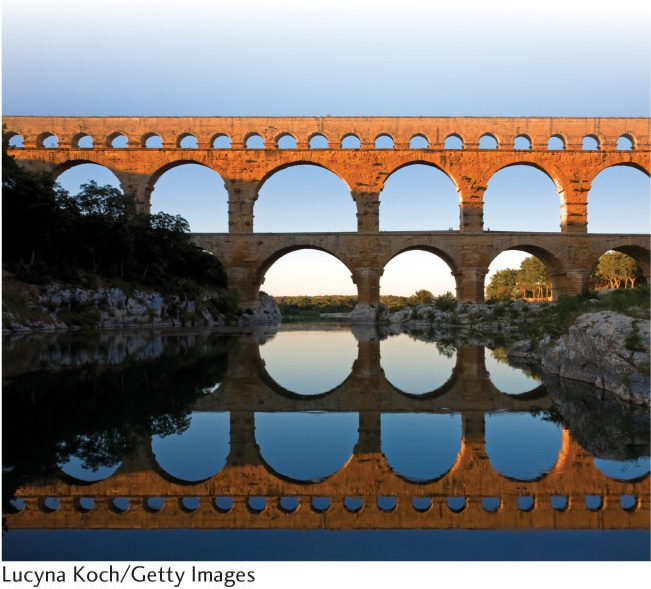

Fundamental to Roman cities was the gridiron street pattern, composed of straight streets intersecting at right angles. Indeed, transportation lay at the heart of Roman cities. Water was transported into cities from remote regions using aqueducts, many of which still punctuate the landscapes of European cities today (Figure 10.9). The Roman Empire itself was held together by a complicated system of roads and highways linking towns and cities. In choosing a site for a new urban settlement, the Romans made access to transportation a major consideration. By 400 c.e., the Roman Empire had declined and so too urban life throughout much of Europe (see Chapter 3, Figure 3.34). The highway system that linked them fell into disrepair, so that cities could no longer exchange goods and ideas. Cities were either destroyed or left to decay on their own, becoming small villages where a few hundred people eked out a living. The urban areas, as with the rest of the territory formerly under Roman rule, fell into the Dark Ages.

421

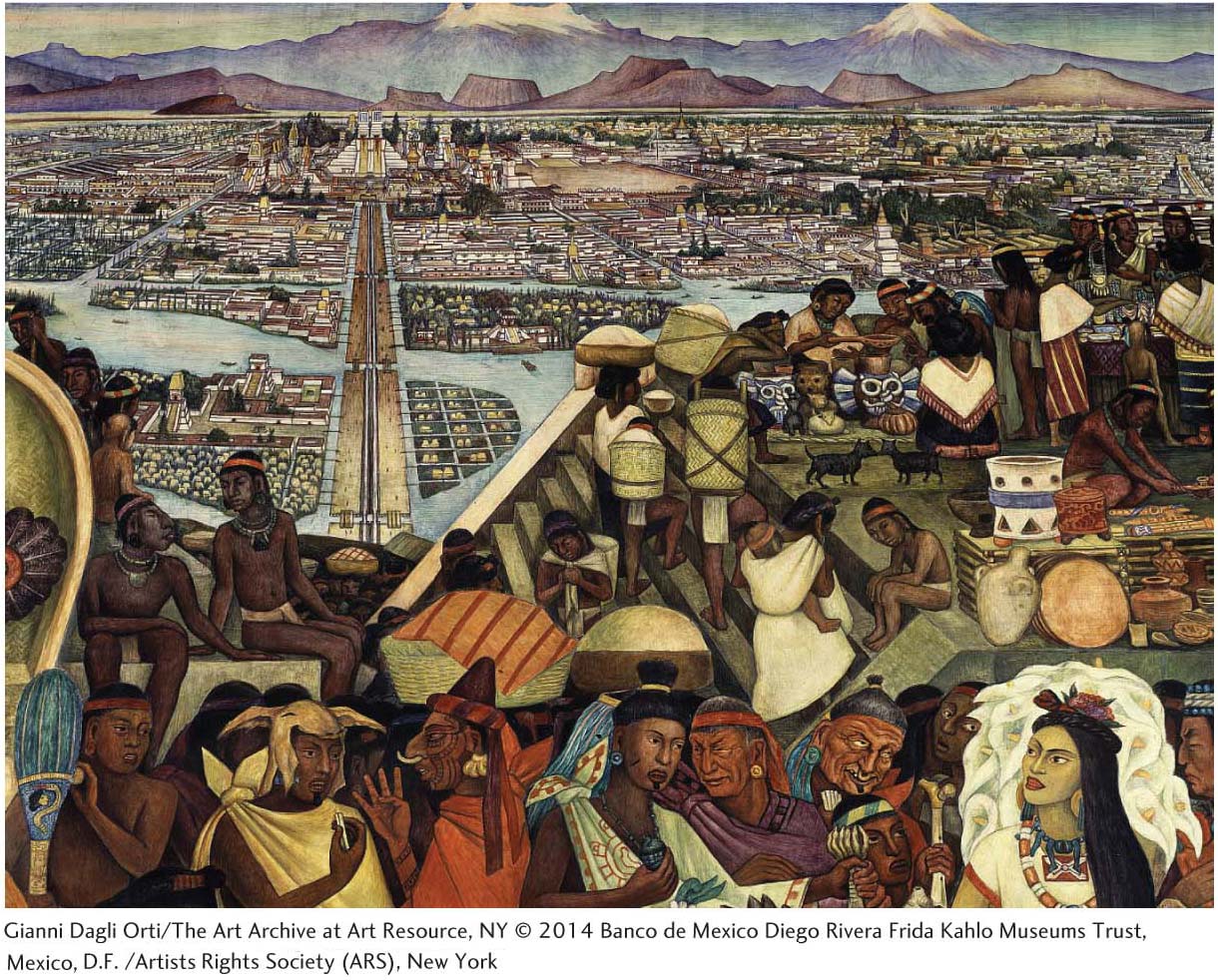

Cities in other parts of Europe and in other world regions, however, thrived. Spanish cities, for example, flourished as centers of learning, commerce, and governance thanks to the North African Moorish imperial presence in Iberia from the eighth through fifteenth centuries. (See the World Heritage Site in Chapter 4 on Alhambra, Generalife, and Albayzín.) Chinese cities developed their own cosmomagical features, including sacred sites connecting residents to ancestors, pagodas that functioned as axis mundi, and fabulous palaces reflecting divine order on Earth (see Figure 10.7). In the Americas, several indigenous cultures established urban centers prior to their colonization by the Spanish in the fifteenth century. American cities were religious ceremonial centers, as well as control centers for the subjugation of surrounding conquered rural peoples. Some grew in size and complexity that outpaced anything that Europeans of the time had experienced.

Tenochtitlan—the Aztec capital now known as Mexico City—was founded in 1325 on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, with canals providing transportation routes within the city and causeways reportedly wide enough to accommodate 10 horses leading to and from the mainland (Figure 10.10). By the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521, the city boasted over 200,000 inhabitants, far outstripping any Spanish city at that time. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a foot soldier in Hernán Cortés’s army, described coming upon it in awe-inspired tones: “And when we saw all those cities and villages built in the water, and other great towns built on dry land, and that straight and level causeway leading to Tenochtitlan, we were astounded. These great towns and cues (temples) and buildings rising from the water, all made of stone, seemed like an enchanted vision.... Indeed, some of our soldiers asked whether it was not all a dream.”

CITIES OF THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The agricultural innovations mentioned in the previous section—primarily, technological innovations leading to the domestication of crops and animals that allowed for the production of a food surplus—permitted the world’s first true cities to develop because they facilitated support of a dense human population in one place, the rise of a nonagricultural class, and the accompanying social differentiation. The connection of agricultural innovations with the rise of cities is often referred to as the first urban revolution.

first urban revolution

The connection between agricultural innovations with the rise of the world’s first true cities.

Cities obviously did not stop evolving, as evidenced by the many differences between early cities such as Tenochtitlan or ancient Rome and the contemporary cities you are familiar with today. Why and in what ways have cities changed over the last six millennia?

422

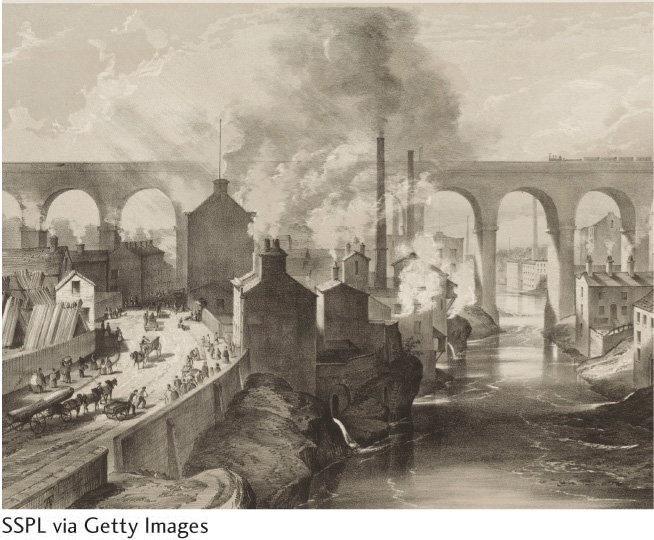

The answer to this question can be traced, in large part, to what scholars term the second urban revolution. Rather than being tied to technological innovations in agriculture, the second urban revolution arose as societies, initially those located in western Europe and later North America, became industrialized. At its heart, the second urban revolution developed from innovations in mining and manufacturing. As industrialization progressed, many transformations occurred in society that fundamentally reshaped cities, both spatially and in terms of the social, cultural, political, and economic functions assumed by cities.

second urban revolution

The connection between industrial innovations with the rise of capitalist cities.

The transformations that culminated in capitalism had begun to reshape the cities of western Europe from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth century. Agriculture became increasingly specialized and commercialized. Land formerly owned and worked collectively became enclosed and owned by individuals who purchased it and then paid others to work the land for them. The very landscape of the European countryside became reorganized (see Chapter 8, Seeing Geography).

Perhaps of greatest significance was how the capitalist mentality introduced a notion of urban land as a source of income. Proximity to the center of the city, and therefore to the most pedestrian traffic, added economic value to the land. Other specialized locations, such as areas close to the river or harbor, or along major thoroughfares into and out of the city, also increased land value.

In the emerging capitalist city, the ability to pay determined where one would live. The city’s residential areas became segregated by economic class. The wealthy lived in the desirable neighborhoods; those without much money were forced to live in the more disagreeable parts of the city—for example, low-lying flood-prone zones, places contaminated by factory waste, or parts of the city located at higher altitudes where roadways and urban services were not easily provided (Figure 10.11).

In earlier urban configurations, there was no separation between one’s home and one’s workplace. For most people, work was organized by family units, it centered on the home, and the workday was governed by the seasons and the rising and setting of the sun. In the capitalist city, the place of work became spatially distinct from the home, such that the laborer had to travel back and forth between them. This spatial separation of work from home, of public space from private space, both reflected and helped to shape the changing worlds of men and women. In general, men generated monetary income from work outside the home and therefore became associated with moving about and occupying the public spaces of the city. Women, who primarily did domestic work, were considered the keepers of the private world of the home and family. They were not monetarily compensated for their labors. This association of women with private domestic space and men with public work space deepened and became more complex over the next few hundred years. (See also Chapter 3 and Chapter 9.)

The center of the capitalist city—its axis mundi— was not the ziggurat, palace, or cathedral, but instead the buildings devoted to business enterprises. A downtown defined by economic activity emerged, and as industrialization progressed, it expanded and evolved into specialized districts. With the downtown devoted to commerce and industry, the upper classes moved to the outskirts of the city and built large houses that displayed their wealth.

423

A Short History of the Highrise

![]() A Short History of the Highrise

A Short History of the Highrise

Part I: Mud (4:30 min): www.tinyurl.com/kqquv4b

Part II: Concrete (7:08 min): www.tinyurl.com/m9tth6q

Part III: Glass (4:20 min): www.tinyurl.com/ktfygst

Part IV: Home (5:52 min): www.tinyurl.com/odlp85a

This series of four videos profiles the evolution of high-rise residential buildings over time and in different places. Innovations in building materials and technology were key to enabling humans to build higher. In addition, social attitudes, conditions, and policies formed a crucial component of whether and how high-rise housing has been adopted in different places and times.

Thinking Geographically:

Figure 10.27 depicts how high-rise urban zones, and individual buildings, tend to look similar throughout the world. These videos, however, note that changing social policies, conditions, and attitudes in regions such as North America, Europe, and Asia have led to very different ways of utilizing—or not—high-rise housing. Give some specific examples from what you have just watched.

People from all urban-based socioeconomic classes, from the very wealthy to the impoverished, have lived in high-rise housing at different points in history. Give some specific examples of the ways in which poor, middle-income, and wealthy occupants have been included or excluded from these dwellings. How has this varied from place to place, as well as historically?

High-rise housing has long had a reputation of being impersonal and ugly. But, some of the buildings you’ve just looked at are very beautiful. What’s beautiful and what’s ugly, in your opinion, about the buildings you’ve seen, with respect to their interiors as well as their exteriors? How do people make these places into their homes?

URBAN LOCATION

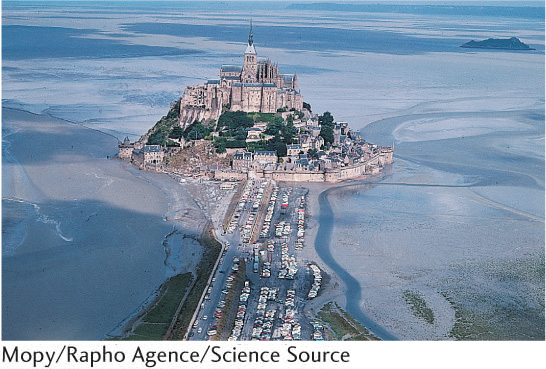

The geographic criteria for city placement changed as industrialization took hold. Early cities tended to be located in places that were easily defended—on islands, hilltops, sheltered harbors, or river bends—or along trade routes (Figure 10.12). Industrial-era cities sought locations near sources of raw materials, such as coal, wood, or metals, used in factories. Location along trade routes continued to be important but the parameters broadened, inasmuch as the waterways, railways, and roadways needed to accommodate increased traffic associated with raw materials entering and finished goods exiting the sites of industrial production (Figure 10.13).

424

Geographers are, as you are no doubt aware by now, fond of using models—including maps—to represent how space is ordered in the abstract, as well as to predict and plan for its optimal ordering. Urban geographers are no exception, and they have used a wide variety of models to understand how urban space is arranged and how to guide its arrangement in better ways. Central-place theory is the term given to a set of models that attempts to understand why cities are located where they are, as well as to help planners position cities in space most efficiently.

central place theory

A set of models designed to explain the spatial distribution of urban centers.

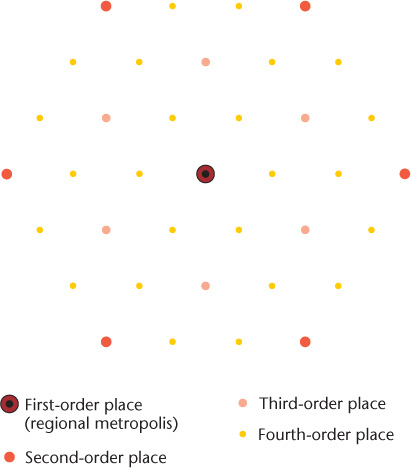

Central place theory is associated with Walter Christaller, a German urban geographer who first published his work on this concept in 1933. Christaller understood cities primarily as economic centers concerned with distributing goods to people, who would travel certain distances to acquire them. According to Christaller, people would travel only short distances to acquire everyday low-order goods such as food and other regularly purchased household items. However, in order to obtain specialized or costly high-order goods and services such as automobiles, the advice of a cardiologist, or to interview for a passport, he hypothesized that people would travel much longer distances. These travel distances dictated the placement of different orders of urban settlements, ranging from tiny hamlets and villages on one end, through towns and cities, and finally to regional capitals (Figure 10.14).

Because people would travel only short distances to acquire the low-order goods sold in smaller urban settlements, there were many villages and hamlets (what Christaller termed fourth-order places) and to a lesser extent towns (third-order places) located relatively close to one another. Each one could be supported by the routine traffic in low-order goods that nobody would travel very far to purchase. In Christaller’s model, smaller urban places have a lower threshold, the number of people required to make provision of a good feasible, and a smaller range, the distance people will travel to acquire a good.

threshold

In central place theory, the size of the population required to make the provision of goods and services economically feasible.

range

In central place theory, the average maximum distance people will travel to purchase a good or service.

425

Costlier and less frequent high-order purchases, however, could only be made in cities (second-order places) and regional capitals (first-order places). This is because people were willing to travel longer distances to obtain high-order goods and services (in other words, big cities have a larger range), while on the other hand, fewer urban areas could actually afford to carry these high-order goods and services because people didn’t purchase them as frequently (in other words, the higher-order goods have a higher threshold).

The requirements of trade-based urban locations continue to shift to this day. For instance, San Francisco’s importance as a West Coast port city was high before the advent of container ships. But once containerized cargo became the norm starting in the 1970s, San Francisco’s piers were no longer needed and there was no room in the city to build the large holding lots needed for containers to go from port to rail. Oakland, San Francisco’s rival city just across the bay, was quick to invest in the large cranes and other equipment needed to handle containers. Oakland was also able to accommodate containerized cargo because it filled in huge tracts of shallow bay lands, creating a massive area for the loading, unloading, and storage of cargo containers. As a result, San Francisco’s importance as a port city declined, and Oakland is now the second-largest West Coast port city (Figure 10.15).

As capitalism shifts from a focus on manufacturing goods and exchanging them for money, and toward the provision of services and information, the question of what constitutes an ideal urban location changes yet again. It is no longer as critical to be located near physical transportation routes as it once was. Indeed, an argument may be made that other sorts of networks, particularly those associated with communications technology, are just as important (if not more so) criteria for city placement. It is worth considering whether the historical legacy of where the world’s major cities are located today will be outweighed by these new considerations, and whether the sites of the important cities of the future will shift accordingly.