CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

10.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Read an urban landscape and identify the trends shaping cities today and into the future.

As you probably already know from your local, regional, or international travels, the look and “feel” of cities varies from place to place. Some cities have bustling downtowns where most of the residents work and perhaps live, while others are characterized by nodes of activities clustered on the suburban fringe; some cities are built around a set of historical buildings with political or religious significance, while the centers of other cities are dominated by new skyscrapers housing financial offices. Finally, some cities’ streets are laid out in a gridlike pattern, while in other cities streets are a crisscrossed jumble without any apparent order.

How can we make sense of this range of urban landscapes? In Doing Geography, you can try your hand at reading the urban landscape in the way that cultural geographers do. Here, we will discuss some of the major trends reshaping the look and feel of cities across the globe: gentrification, efforts to create more livable cities, and movements to “take back the city” from developers who have increasingly privatized formerly public urban spaces.

GENTRIFICATION

Beginning in the 1970s, urban scholars began to observe what seemed to be a trend opposite to suburbanization. This trend, called gentrification, was the movement of upper-middle-class people into deteriorated areas of city centers (see also Chapter 2). Today, some older suburbs are becoming gentrified, as well as some neighborhoods that began their lives as shantytowns (as we saw earlier with respect to Mexico City; Figure 10.33). Gentrification often begins in an inner-city residential district, with gentrifiers moving into rundown housing or even spaces that didn’t start out as housing—for example, warehouses. These places are more affordable than newer suburban housing and are often closer to workplaces or mass transit lines. The infusion of new capital into these neighborhoods usually results in higher property values, and this, in turn, often displaces existing residents who cannot afford the higher prices. The displaced residents are disproportionately poor, immigrant, and racialized populations. Their displacement opens up even more housing for gentrification, and the gentrified district continues its spatial expansion.

gentrification

The displacement of lower-income residents and economic activities by higher-income residents and activities; frequently associated with a restoration of buildings in deteriorated areas of the city.

447

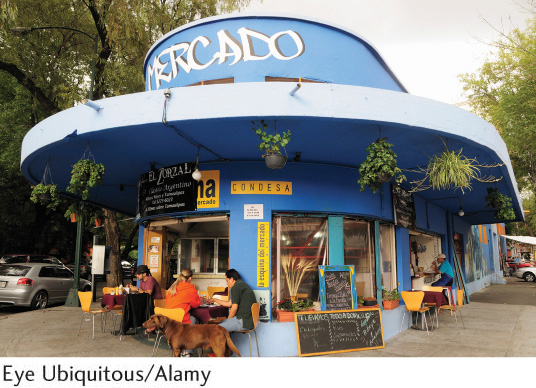

Commercial gentrification usually follows residential gentrification, as new patterns of consumption are introduced into the inner city by the middle-class newcomers. Pedestrian shopping districts with expensive boutiques and art galleries attract cultural consumers, and bars and restaurants catering to this new urban middle class provide entertainment and nightlife for the gentrifiers (see Figure 10.18).

The speed with which gentrification has proceeded in many of our cities, and the extent of changes—in the urban landscape, but also culturally, economically, and politically—that accompany gentrification are causing dramatic shifts in the urban fabric. What factors have led to gentrification?

Economic Factors Some urban scholars look to broad economic trends to explain gentrification. Throughout the post-World War II era in North America and Europe, most investments in metropolitan land were made in the suburbs; as a result, land in the inner city was devalued. By the 1970s, many home buyers and commercial investors found land in the city much more affordable, and a better economic investment, than in the higher-priced suburbs. This situation brought capital into areas that had been undervalued and accelerated the gentrifying process.

In addition, most Western countries have been experiencing deindustrialization, a process whereby the economy is shifting from one based on secondary industry to one based on the service sector. This shift has led to the abandonment of older industrial districts in the inner city, including waterfront areas. Many of these areas are prime targets of gentrifiers, who convert the waterfront from a noisy, commercial port area into an aesthetic asset. In Buenos Aires, for example, one of the new gentrified neighborhoods is Puerto Madero, an area that was once home to docking facilities and a wholesale market (Figure 10.34; see also Mona’s Notebook below). The shift to an economy based on the service sector also means that the new productive areas of the city will be dedicated to white-collar activities. These often take place in relatively clean and quiet office buildings, contributing to a view of the city as a more livable environment.

deindustrialization

The decline of industry, accompanied by a rise in service and information sectors of the economy.

Political Factors Many metropolitan governments in the United States, faced with the abandonment of the central city by the middle class and therefore with the erosion of their tax base, have enacted policies to encourage commercial and residential development in downtown areas. Some policies provide tax breaks for companies willing to locate downtown; others furnish local and state funding to redevelop central-city residential and commercial buildings.

At a more comprehensive level, some larger metropolitan areas have devised long-term planning agendas that target certain neighborhoods for revitalization. Often this is accomplished by first condemning the targeted area, thereby transferring control of the land to an urban-development authority or other planning agency. Such areas are frequently older residential neighborhoods originally built to house people who worked in nearby factories, which have usually been torn down or transformed into lofts or office space. The redevelopment authority might locate a new civic or arts center in the neighborhood. Public-sector initiatives often lead to private investment, thereby increasing property values. These higher property values, in turn, lead to further investment and the eventual transformation of the neighborhood into a middle- to upper-class gentrified district.

448

449

Sexuality and Gentrification Gentrified residential districts are often correlated with the presence of a significant gay and lesbian population (Chapter 2). It is fairly easy to understand this correlation. First, the typical suburban life tends not to appeal to people whose lifestyle is often regarded as different and whose community needs frequently diverge from those of people living in the child-centric suburbs. Second, gentrified inner-city neighborhoods provide access to the diversity of city life and amenities that often include gay cultural institutions. In fact, the association of urban neighborhoods with gays and lesbians has a long history. For example, urban historian George Chauncey has documented gay culture in New York City between 1890 and World War II, showing that a gay world occupied and shaped distinctive spaces in the city, such as neighborhood enclaves, gay commercial areas, and public parks and streets.

Yet, unlike this earlier period, when gay cultures were often forced to remain hidden, the gentrification of the postwar period has provided gay and lesbian populations with the opportunity to reshape entire neighborhoods actively and openly. Indeed, many geographers have explored how gays and lesbians played very influential roles in the gentrification of certain neighborhoods, which have become heavily identified with these populations. Other geographers have focused on black gentrifiers in New York’s Harlem and Chicago’s South Side neighborhoods. Both areas of work underscore that it is not always affluent whites who are the primary movers and shakers in gentrification. More recently, however, urban geographers have pointed out that while these contributions are important, it is vital to remember gentrification is mostly driven by and for affluent white urban populations.

The Costs of Gentrification Gentrification often results in the displacement of lower-income people who are forced to leave their homes because of rising property values. This displacement can have serious consequences for the city’s social fabric. Because many of the displaced people come from disadvantaged groups, gentrification frequently contributes to racial and ethnic tensions. Displaced people are routinely forced into neighborhoods more peripheral to the city, a trend that only adds to their disadvantages. In addition, gentrified neighborhoods usually stand in stark contrast to surrounding areas where investment has not taken place, thus creating a very visible reminder of the uneven distribution of wealth within cities.

The success of a gentrification project is usually measured by its appeal to an upper-middle-class clientele. Indeed, the so-called hipster gentrifiers—artists, musicians, youth, and other creative types initially attracted to these lower-cost neighborhoods—are often displaced by later waves of wealthier incomers who find the “cool factor” of such up-and-coming neighborhoods irresistible. Richard Campanella refers to the final wave as “bona fide gentry, including lawyers, doctors, moneyed retirees, and alpha professionals from places like Manhattan or San Francisco.” Thus, gentrification ultimately gravitates toward the suburban notion of residential homogeneity, eliminating what many people consider to be a great asset of urban life: its diversity and heterogeneity.

Mona’s Notebook: “Seeing” New Places

Mona’s Notebook

“Seeing” New Places

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As a cultural geographer, I’ve thought a bit about how people often see new places through the “eyes” of familiar ones. You, too, have most likely noticed this. For example, when you travel somewhere new, you often compare it to what you know, saying things like “This street reminds me of the one I grew up on” or “Don’t we have almost an identical building in our town?” I shouldn’t have been surprised then when on a trip to Argentina I noticed that parts of Buenos Aires looked like other cities I was familiar with, particularly the recently gentrified neighborhoods in the city (see Figure 10.34). The brick, four-story buildings that had once lodged warehouses and now were home to fancy apartments and upscale restaurants and bars looked to my North American eye to be almost identical to the gentrified waterfronts of Boston and New York City. But, they weren’t. There are similarities, of course, since these waterfronts served similar purposes in the past, but each city and its history have put a particular stamp on its urban landscape. Boston’s gentrified waterfront, for example, was built much earlier and in a style different from the Buenos Aires waterfront, and granite was used as a building material as much as brick.

I was surprised, however, when I visited other parts of Buenos Aires and realized that some neighborhoods were making explicit their similarity to and connection with North American cities through their place-names. Fairly recently, Palermo, a neighborhood in the process of gentrification in northeast Buenos Aires, has been subdivided into smaller districts, including Palermo Soho and Palermo Hollywood. The name Palermo itself is already a place-name taken from somewhere else (a relatively common feature of immigrant nations), but the twinning of that now well-established name with Soho and Hollywood was something new to me. As it turns out, I learned that other places in the world have taken the Soho name and used it to lend a certain trendy and hip connotation to their neighborhoods. Most likely, developers and entrepreneurs thought that using Soho, a term derived from South of Houston Street (a very chic neighborhood of lofts and trendy restaurants and bars in New York City), would boost the area’s commercial potential. And, the global symbol of Hollywood, I realized, needed no explanation: it connoted a West Coast version of glamour. The local and the global often meet in very interesting ways!

THE LIVABLE CITY

Probably for as long as humans have lived in cities, there have been some who have dedicated themselves to contemplating exactly what makes city life so attractive, pondering as well how we might go about making it better. Some five thousand years ago, urbanites in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus River Valley planned their cities to have straight streets that intersected at right angles and devised drainage systems. Since then, we have attempted to invent better—more beautiful and more efficient—ways to house, employ, and entertain city residents; to convey people and the things they need within cities and between them; and to fortify cities for defense from attack.

450

What makes a city livable? In many ways, the answer to that question depends on who you ask. Certainly, beautiful surroundings—natural and man-made—are important. Clean air and water, public transit, freedom from crime, historical importance, accessibility, affordability—all of these factors and more are also vital components of making a city not just livable, but truly great. Indeed, making the list of “the world’s most livable cities” is something many cities would like to achieve; you might not be surprised to learn then that many such lists exist. And, given that there is no real way to measure and thereby quantify many of the positive aspects of cities listed above, a lot of subjectivity goes into compiling these lists. In 2012, for instance, Melbourne, Australia, was at the top of the Economic Intelligence Unit’s “Most Livable Cities” list. Yet, other listings place Vienna or Copenhagen in the top spot. All of the lists, however, skew notably toward Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and continental Europe.

Refocusing cities on people seems to be at the heart of movements to make cities more livable. Moving away from individually owned and operated automobiles as the drivers, literally and figuratively, of our cities is part of the solution (Figure 10.35). As we discussed earlier in this chapter, more and more cities are adopting bike- and car-sharing programs and encouraging mass transit, carpooling, biking, and walking as inexpensive and less polluting ways to get around.

As our reliance on the automobile decreases, cities can be reshaped. No longer beholden to paved roadways, parking lots and garages, and long hours commuting alone in cars across sprawling urban jungles, people are freer to spend time in their neighborhoods. Space becomes available for meeting places such as plazas, parks, and pedestrian areas. With fewer automobiles, city spaces become safer for bicyclists and pedestrians. Danish architect Jan Gehl describes the multiple activities that city residents can engage in when they inhabit more livable city spaces: “purposeful walks from place to place, promenades, short stops, longer stays, window shopping, conversations and meetings, exercise, dancing, recreation, street trade, children’s play, begging and street entertainment.”

THE RIGHT TO THE CITY

Throughout this chapter, we have noted the processes that change cities—their layout, demographic profile, ecology, and what it means to live in them—affect people differently. Almost invariably, immigrants, racialized minorities, and the impoverished experience negative consequences stemming from urban transformations. These are the people who are displaced when neighborhoods gentrify. They are most at-risk from natural disasters and climate change. They have the least access to transportation, housing, and urban services.

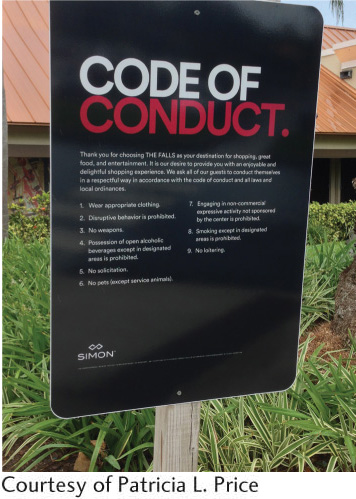

We have also seen, for instance in the case of gated communities discussed earlier in this chapter, that some processes at work in cities are explicitly aimed at excluding disadvantaged people from access to certain parts of the city. To provide an additional example, think about the last time you visited a shopping mall. Did you see a sign like the one pictured in Figure 10.36? Though it may come as a shock to many young people, shopping malls are, in fact, not public spaces. While they may look open to the public—indeed, some open-air shopping malls are not enclosed by any physical barrier such as walls or fences—most shopping malls are owned by developers and function as private spaces. The mall developers look out for the business interests of their tenants: stores renting spaces in the mall. When groups of youths, or homeless individuals, use shopping malls for social gatherings, to take care of daily needs like sleeping or bathing, or as venues for begging, they are swiftly escorted from the premises. If they return, such individuals can be cited for trespassing or even disturbing the peace. Why? As one developer put it, his Albany, New York, mall “had become a babysitting service . . . with thousands of teen mall rats roaming around.” Rambunctious crowds of teens at the food court and theater entrance were seen as frightening away older shoppers.

451

But, what about the truly public spaces of cities: the parks, pedestrian promenades, plazas, libraries, sidewalks, and beaches? Are certain people denied access to public urban spaces? The answer, unfortunately, is yes. What urban scholar Henri Lefebvre called the right to the city, specifically the right of all urban residents to be in and move through public urban places, is becoming increasingly curtailed. More of these spaces are becoming private property, and developers can then decide who stays and who goes. Some beaches, for instance, have been purchased by hotel and condominium developers who then restrict access to them to residents and guests only. Surveillance technologies such as drones and cameras may be used to watch people in public spaces and have them removed based on what is deemed threatening or disruptive behavior. The spaces themselves may be configured in ways that make them inaccessible to certain people or for certain purposes. This area of urban planning goes by the name of “crime prevention through environmental design.” For instance, benches in waiting areas for public transit are often constructed in ways that deter people from sleeping on them (Figure 10.37).

right to the city

The notion that all urban residents, not just the privileged, should be able to access city spaces and have a voice in how the city is shaped and used.

Are our cities made more or less livable by such measures? What is lost when access to city spaces is curtailed? What is gained? Who benefits, and who suffers?

452