MOBILITY

11.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain how current trends will shape future mobilities.

Movement on a global scale—of ideas, people, money, and commodities—in many ways will characterize the future. The computer, the Internet, satellite television, smartphones, and other globally available technologies greatly facilitate access to and the diffusion of ideas and information, while also accelerating their spread. At the same time, the spread of new ideas and innovations often produces disruptions that change the world in unexpected and unintended ways. At the very least, the theme of mobility cautions us against counting on predetermined outcomes.

466

MOBILITY IN THE DIGITAL AGE

The Internet allows ideas, music, artwork, money, and indeed any form of cultural expression that can be turned into digital data to be transmitted around the world in a matter of seconds. With the development of the Internet and rapid global transportation systems, transnational corporations are able to advertise, market, and deliver virtually anywhere. Almost all transnational companies manage globally accessible web sites that not only sell products, but also sell the company “brand” (its identity and business model) in an effort to build a global base of loyal customers. Any entrepreneur in any part of the world can open a web site, allowing him or her to market cultural products directly to consumers in every corner of the globe. What’s more, nongovernmental organizations, art museums, indigenous peoples, individual artists and musicians, and just about all imaginable culture groups or producers of culture have their own web sites. Increasingly, social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are linking individuals, communities, governments, and corporations in a complex global network of information sharing. In 2013 industry analysts estimated that Twitter was registering 135,000 new users every day!

The Internet clearly has profoundly altered the speed and character of cultural interaction, but to what effect? The spread of more democratic forms of governance, for example, has accompanied the more rapid movement of information over the Internet. Dictatorships thrive by controlling and manipulating information—an increasingly difficult task in the age of the Internet. And, the Internet is certainly not the only means by which information spreads rapidly. Smartphones that utilize microwave towers and Wi-Fi and global television networks that utilize satellite communications are integral to a worldwide network of digital transmission that is growing in complexity and reach. Social media and mobile devices have played visible roles in organizing new social movements, such as the so-called Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street (Figure 11.7). Although the importance of social media in fomenting democratic revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East is a continuing debate, the Egyptian and Libyan governments felt threatened enough to shut down Internet access nationwide during the height of street protests calling for reform.

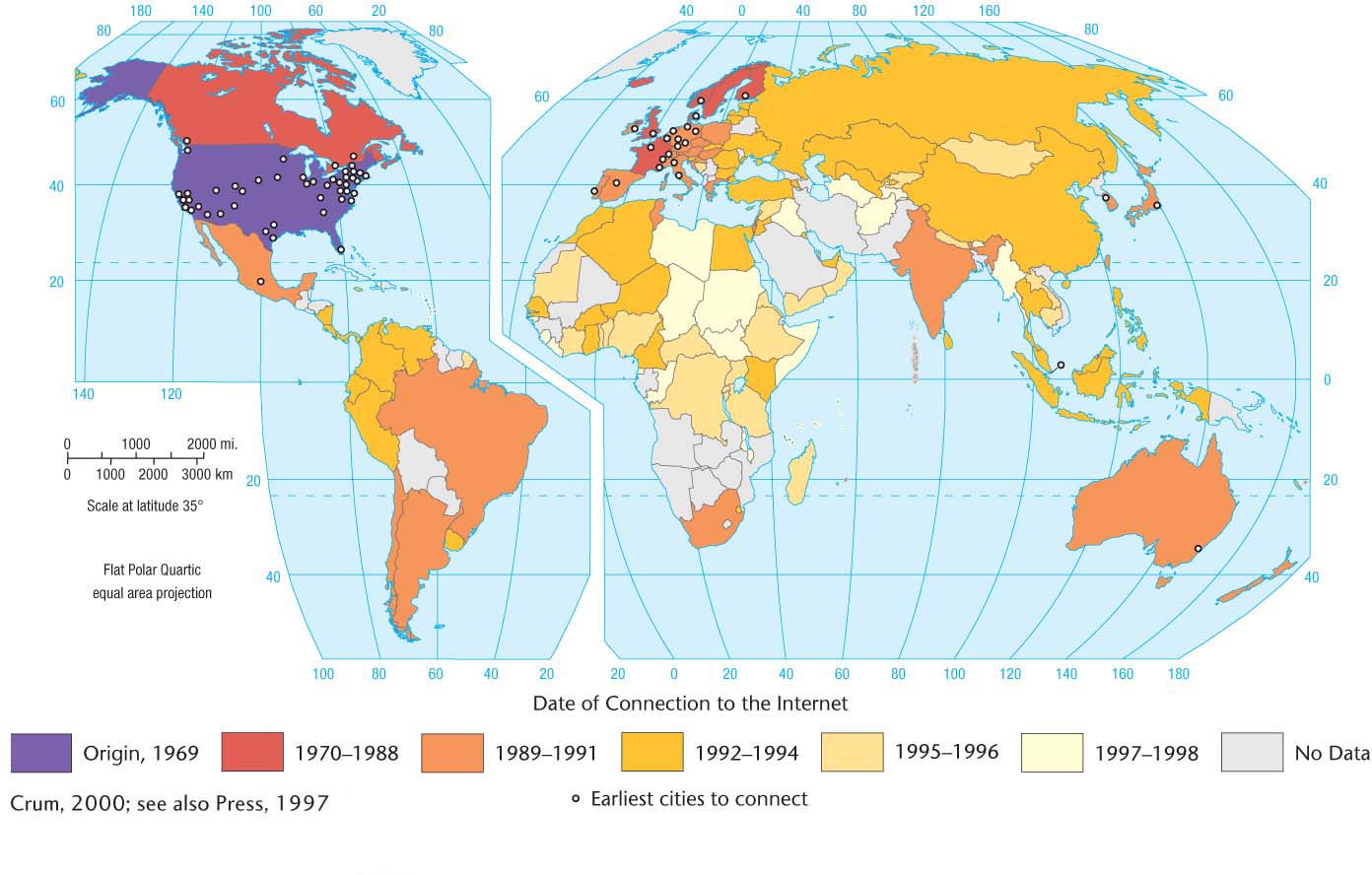

The theme of mobility also applies to the spread of the Internet itself. If the future is to bring the universal diffusion of cultural elements, then surely this new homogenizing tendency ought to be revealed in the spread of this most essential element of globalization (Figure 11.8). The diffusion of the Internet has now spread across much of the world, following the models established in Chapter 1.

Although the Internet now reaches into almost every land, its use varies profoundly (see Figure 11.6 and Figure 11.8). Barriers to access include inadequate infrastructure, poverty, and tyrannical governments. Nonetheless, current trends suggest a near universally connected world. For example, by one industry estimate, there are already 650 million mobile phone users in Africa, the world’s poorest region. As the price of smartphones and other mobile computing devices declines, the Internet will become available to hundreds of millions more people in Africa. Google’s CEO believes that the spread of mobile devices will make it possible for virtually the entire world to be connected through the Internet by 2020. Speculation on how these developments in digital mobility will shape the cultural geography of the future would fill another textbook.

467

NEW (AUTO) MOBILITIES

Back in the mid-twentieth century, there was much popular debate about the future of transportation in the United States. People speculated that anything from a national network of high-speed railways to nuclear-powered flying machines would replace automobiles (Figure 11.9). Hardly anyone predicted that the twenty-first century would be more of the same old thing: the internal combustion engine-propelled family car. No one predicted that the American fascination with the automobile would diffuse to East and South Asia. At that time, these regions were largely agricultural, facing recurring famine, and among the poorest regions of the world.

468

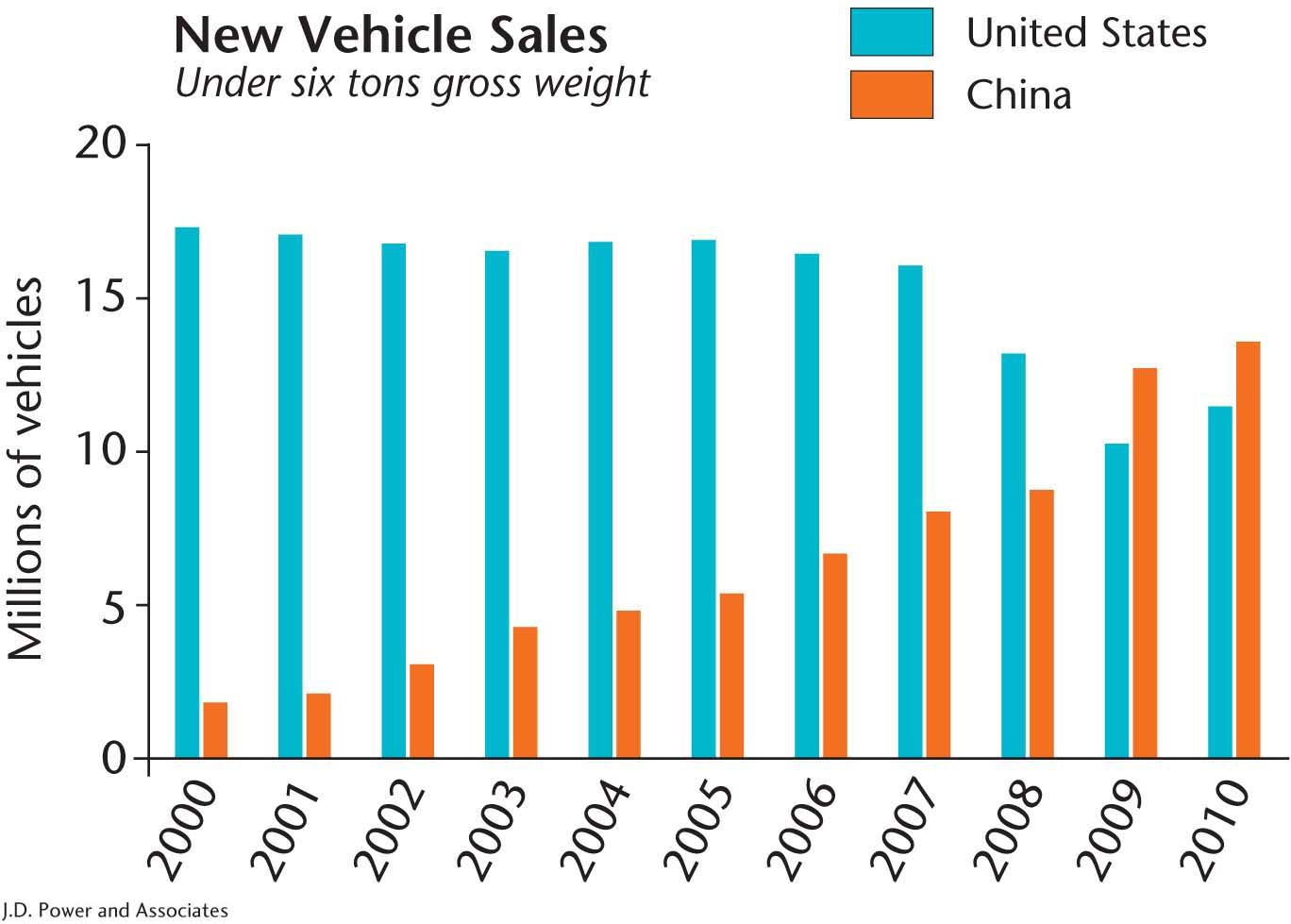

In 2010, however, China overtook the United States to become the largest automobile market in the world in terms of both sales and production (Figure 11.10). By 2012 China accounted for an astounding 23.6 percent of worldwide auto sales. As a region, Asia now boasts the world’s fastest-growing national auto markets, including such relative newcomers to the mass consumption race as Indonesia and Thailand. India has emerged as the region’s third largest exporter of passenger cars behind only Japan and South Korea. It is forecast to become one of the world’s three big auto manufacturers by 2030, with China number one and the United States number two.

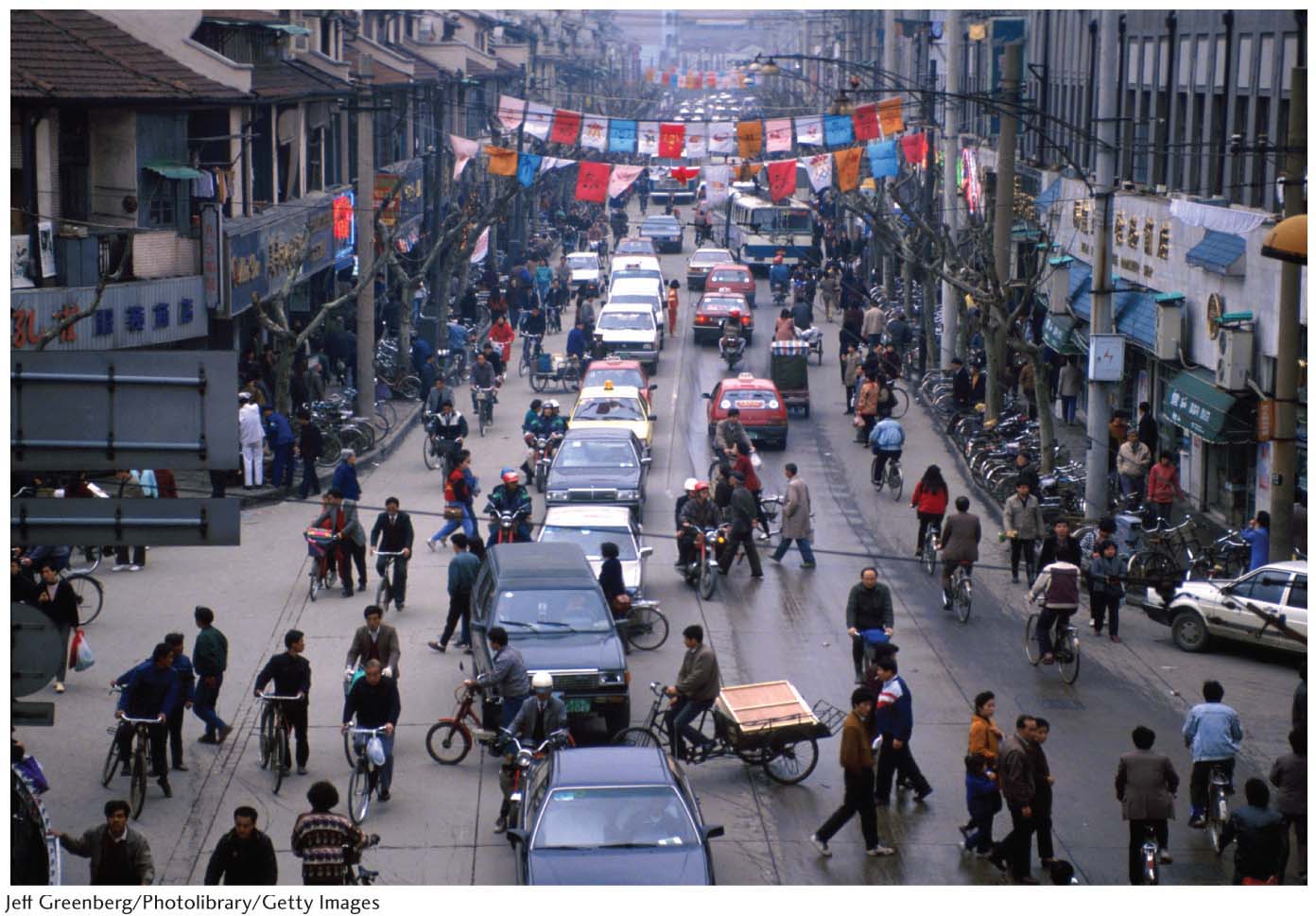

The transformation in China’s urban culture is as profound as it is sudden, with cars now clogging city streets built for pedestrians and bicycles (Figure 11.11). At the end of the twentieth century, only state bureaucrats bought cars and there were only six models from which to choose. Now Volkwagen alone has twenty models on the market and dozens more foreign and domestic automakers are on the scene offering hundreds of models. Businessmen, flush with profits from China’s economic boom, are paying cash. Sales for premium (i.e., luxury) autos are growing at a faster rate than overall sales. China has already surpassed the United States as BMW’s largest market, and it is likely that China will also surpass America in total luxury car sales by 2017.

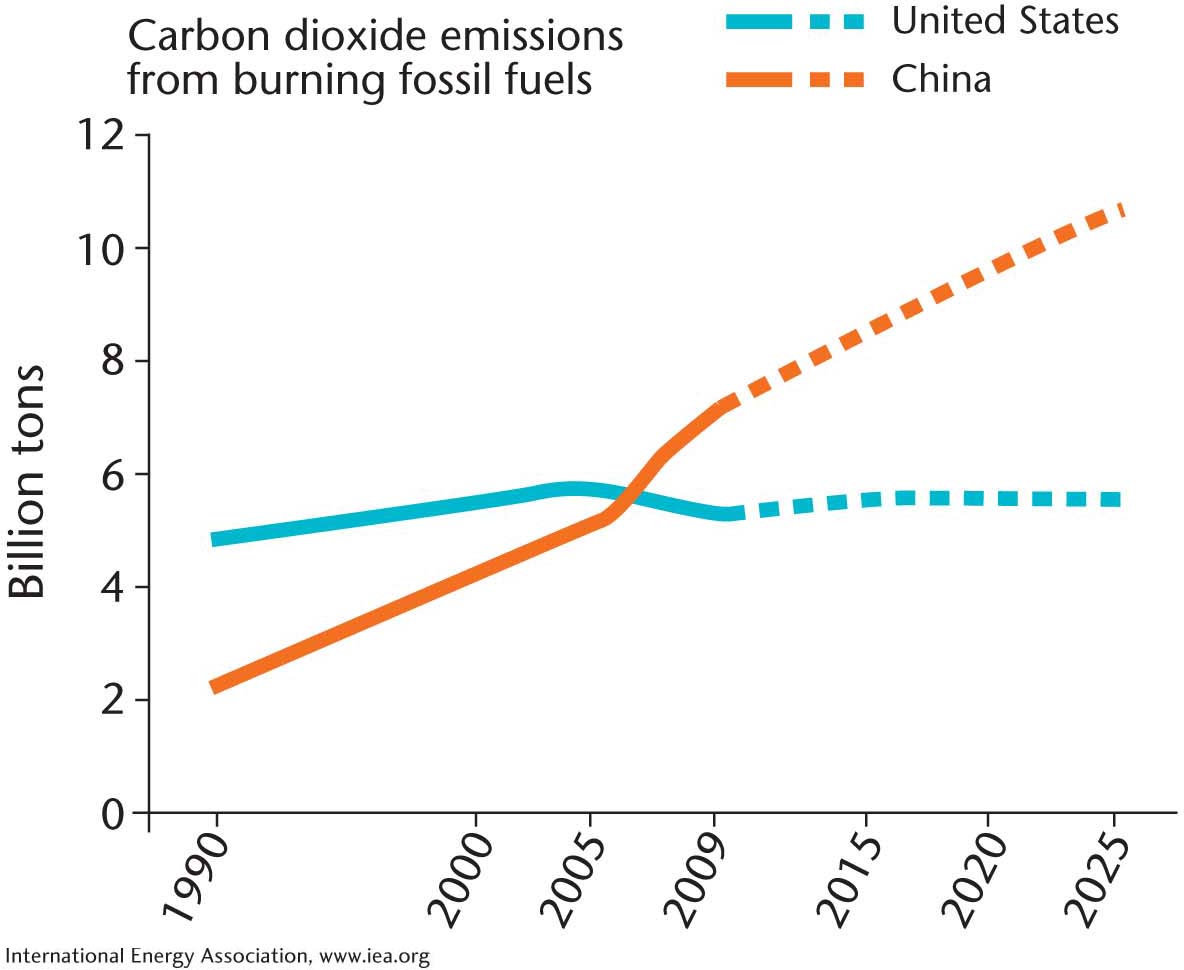

Crowding and associated pollution will only intensify in the future as cities such as Beijing register 1000 new drivers every day. The environmental consequences of expanding automobile sales are numerous and of global importance. Beijing, Shenyang, and Shanghai are ranked among the world’s 10 worst cities for air pollution. Among the biggest concerns is the increase in carbon dioxide emissions, caused by increased car exhausts, auto-manufacturing activities, and power plant growth to meet manufacturing demands for electricity. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that is the main contributor to the problem of global warming. China has overtaken the United States as the world’s number-one source of carbon dioxide and its 2000 emissions are expected to double by 2020 (Figure 11.12).

469

American auto manufacturers have scrambled to gain a foothold in emerging markets such as China. General Motors Corporation, for example, began establishing manufacturing plants in China in the late 1990s (Figure 11.13). It now is involved in nine joint ventures and two wholly owned foreign enterprises in China covering all aspects of the auto industry, including vehicle manufacturing, sales, financing, and parts distribution. Shanghai went from 5 GM dealerships in 2000 to 27 in 2010! Nationwide, GM’s current network of about 3500 dealerships rivals its U.S. network of 4400. Carmakers are betting that the symbolic importance of the luxury automobile will diffuse to not only China but also other regions of East and South Asia. For example, Buick, GM’s top model in China, is perceived as plush, elegant, and an indicator of high social standing. It appears as though a prime status symbol in American middle-class culture is poised to become the same for a new global middle class (Figure 11.14).

470

MIGRATION FUTURES

What can we say about the range of possible futures for human migration? Looking at past experience is helpful, but imprecise. As long as there are environmental disasters, global-scale economic inequalities, and civil wars, we know diasporas will occur. Predicting where diaspora cultures will emerge and when, however, is much more difficult. Unpredictable events aside, tracking trends can provide insight on the future. We would, nevertheless, have to answer a range of questions about demographics, national economic trends, and basic geography, such as location and proximity.

Mexican immigration to the United States illustrates the complexities of trying to predict migration futures. By the start of the twenty-first century, Mexico was by far the single biggest source of the foreign-born population in the United States, exceeding all other Latin American and Caribbean countries combined. However, a close examination of current trends suggests that the main migration from Mexico to the United States has already peaked and is rapidly subsiding. For instance, demographic trends in Mexico show a rapidly declining fertility rate and leveling population growth rate. Mexico’s basic socioeconomic indicators, such as education and income levels, are trending upward. The Mexican national economy continues to diversify, creating more domestic jobs for an expanding middle class, and the wage gap between Mexico and the United States has decreased. Moreover, political and economic changes throughout Latin America have resulted in new migration patterns, particularly an increase in movement within regions. In short, many of the push and pull factors that led to the explosion of Mexican migration to the United States from the 1970s through the 1990s have dissipated. We would need to do similar, and much more complex, comparative analyses of national demographics and socioeconomic indicators to make specific predictions about future international migrations.

Trends of greater temporal and spatial scale than the case of Mexico and the United States allow for more certainty in predicting migration futures. The rural-to-urban migration trend that began with the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe and became a global trend in the twentieth century will likely continue through the twenty-first. Countries in East Asia, such as China and Indonesia, are urbanizing faster than any prior country in history. Africa is following close on the heels of Asia. Populations are urbanizing across the continent and Lagos, Nigeria, became the world’s third largest city in 2015 (Figure 11.15) On a global scale, humanity hit a benchmark in 2008 when for the first time in history over half of the world’s population were living in cities. By 2030 the United Nations predicts that at least 60 percent of the world’s population will live in cities, with further urbanization expected through the century. We can be relatively certain that rural-to-urban migration will continue to transform the human experience worldwide.

THE PLACE(S) OF THE GLOBAL TOURIST

Tourism will be one of the key types of mobility of the twenty-first century. By some estimates, tourism is or soon will be the largest industry in the world, second only to oil as the most important source of revenue for the Third World. Cultural geographers are increasingly interested in understanding this phenomenon. What sort of cultural interactions will take place under global tourism? Will the end result be the preservation, conversion, or elimination of distinct culture regions?

471

As with many global-scale patterns of mobility, there are distinct differences in power that structure the tourist experience. The most glaring inequality is that between the visiting and visited cultures. The vast majority of global tourists are from the First World. The cultures visited are often located in the marginalized sites of the global economy, such as on popular African safaris or spring-break excursions to Cancún, Mexico.

The global tourist industry presumes the existence of unique places that appear “exotic” to the Westerner—or at least serve to emphasize the difference between the experience of home and the experience of the travel destination. Tourism can thus be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, there is an imperative to preserve and nurture folk and indigenous cultures, and, on the other, an imperative to merely create the illusion of cultural difference. The former imperative can gain support from tourism, such as in the case of agricultural tourism, where traditional but uneconomical food production persists with the aid of profits gained from tourist visits. For example, the European Union provides funds to member states to support the production of a range of traditional agricultural products such as local cheeses and rare livestock breeds. The EU believes that these investments keep rural economies intact and spark the tourist trade because urbanites and foreign tourists are attracted to the countryside to sample unique and historically significant agricultural products. The latter imperative is often driven by commercial enterprises that make their profits from entertaining their customers with sights and sounds of the “exotic.” In such cases, “traditional” dress and performance is for the benefit of tourists, not a part of everyday life (Figure 11.16). Some cultural geographers have concluded from these observations that the tourism business packages its offerings to conform to the tastes of the affluent global tourist and so results in an “inauthentic” experience of place.

It would be wrong, however, to simply view local cultures as “made up” or “invented” by the global tourism industry or to suggest that only inauthentic cultural interactions are possible (see Rod’s Notebook). Geographers Peggy Teo and Lim Hiong Li’s study of global and local interactions at a tourist site in Singapore—a former private mansion and fantasy garden—provides an excellent case in point. They favor the view that local groups can use the forces of global tourism to strengthen their cultural identities and traditions. Their study focused on a government-sponsored effort to create from the mansion and garden an “Oriental Disneyland,” a Western-style theme park loosely based on Disney’s technologically enhanced tourist attractions. After the venture failed, local people successfully lobbied the government to redesign the site to more closely replicate its original condition. The motivation behind these efforts was to defend local cultural and historical meanings associated with the site. They conclude that “the global does not annihilate the local.” Rather, tourism can result in “unique outcomes in different locations.”

472

Rod’s Notebook: Rethinking Global Tourism on the Quetzal Quest

Rod’s Notebook

Rethinking Global Tourism on the Quetzal Quest

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As dusk became night on the narrow two-lane highway climbing Costa Rica’s Cerro de la Muerte (Mountain of Death), we leaned toward the windshield, scanning for some sign of our destination. We knew from the web site we had visited back home that we could expect a crude wooden sign signaling the turnoff. We had come for a glimpse of the resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno), a bird revered by ancient Aztecs and contemporary nature tourists alike, though no doubt based on very different sets of cultural values. We found our way down a muddy track to a random collection of rough-hewn wooden buildings. The owner of the finca (farm), a solidly built farmer with a crooked smile, served us rice and beans and cold beer. It was a delightful and memorable meal.

Our experience in the quetzal’s cloud forest home led me to ponder the meaning of the term global tourism and Western tourists’ endless quest for the authentic encounter. Global tourism seems to imply huge institutions or corporations shuttling masses of camera-toting vacationers to every corner of the world. Clearly, there were many multinational corporations involved in this tourist encounter, beginning with the airline that had transported us from Miami to San José. On the other hand, the key global entity in this story was the worldwide Internet, which put us in direct contact with a peasant farmer high in the mountains 1995 kilometers away. And although we were “global tourists,” we were also guests of the farm owner. Our host had been born and raised on this steeply tilted piece of forest that happened to be key quetzal habitat. Our conversations at mealtimes and predawn bird-watching adventures had a feeling of intimacy absent in large, packaged tours. There was no sense of alienation or performance. We talked about his childhood in the mountains, farming, and forest conservation. I came away from our experience thinking that the degree of authenticity in the tourist encounter has a lot to do with who owns the means of producing the tourist experience.

473