MOBILITY

4.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze how languages and dialects have come to exist.

Different types of cultural diffusion have helped shape the linguistic map. Relocation diffusion has been extremely important because languages spread when groups, in whole or in part, migrate from one area to another. Some individual tongues or entire language families are no longer spoken in the regions where they originated, and in certain other cases the linguistic hearth is peripheral to the present distribution (compare Figures 4.2 and 4.6). Today, languages continue to evolve and change based on the shifting locations of peoples and on their needs as well as on outside forces.

INDO-EUROPEAN DIFFUSION

How did Indo-European languages arise and spread, to become the largest language family on Earth? One theory suggests that the earliest speakers of the Indo-European languages lived in southern and southeastern Turkey, a region known as Anatolia, about 9000 years ago. According to the Anatolian hypothesis, the initial diffusion of these Indo-European speakers was facilitated by the innovation of plant domestication. As sedentary farming became adopted throughout Europe, a gradual and peaceful expansion diffusion of Indo-European languages occurred. As these people dispersed and lost contact with one another, different Indo-European groups gradually developed variant forms of the language, causing fragmentation of the language family.

Anatolian hypothesis

A theory of language diffusion holding that the movement of Indo-European languages from the area in contemporary Turkey known as Anatolia followed the spread of plant domestication technologies.

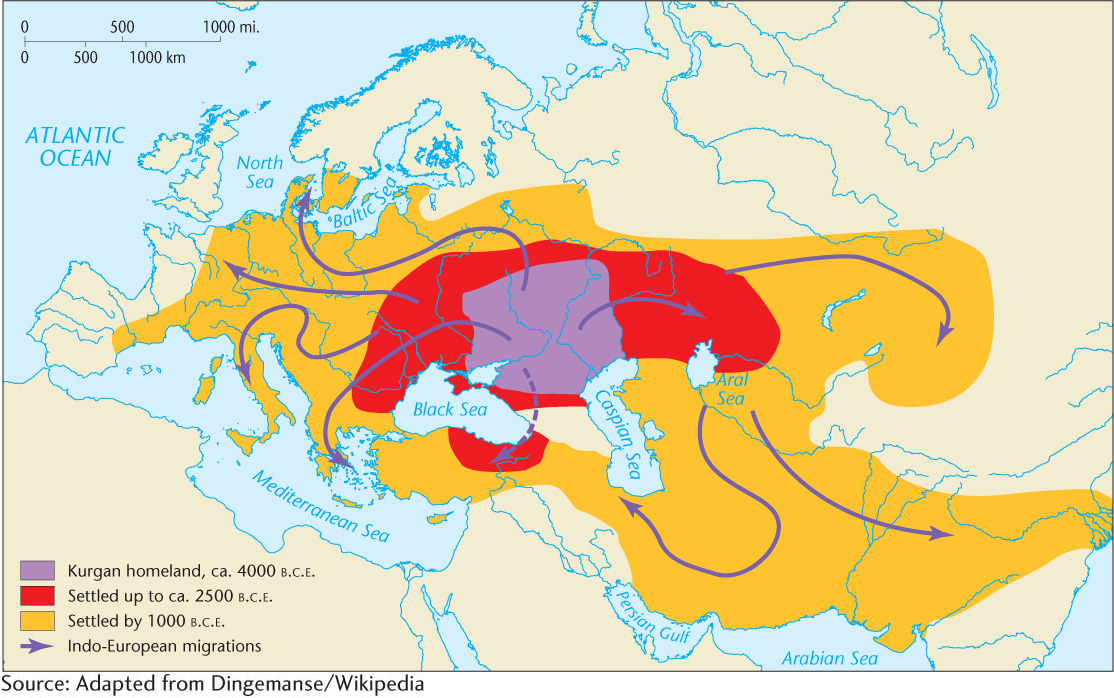

The Anatolian hypothesis has been criticized by scholars who note that specific terms related to animals (particularly horses), as opposed to agriculture, appear to link Indo-European languages to a common origin. The so-called Kurgan hypothesis, which is more widely accepted than the Anatolian hypothesis, places the rise of Indo-European languages in the central Asian steppes only 6000 years ago (Figure 4.6). It asserts that the spread of Indo-European languages was both swifter and less peaceful than is maintained by those who subscribe to the Anatolian hypothesis. The domestication of horses by militaristic Kurgans allowed them to overtake the more peaceful agricultural societies and to rapidly spread their languages through imposition. No one theory has been definitively proven.

Kurgan hypothesis

A theory of language diffusion holding that the spread of Indo-European languages originated with animal domestication in the central Asian steppes and grew more aggressively and swiftly than proponents of the Anatolian hypothesis maintain.

What is more certain is that in later millennia, the diffusion of certain Indo-European languages—in particular, Latin, English, and Russian—occurred in conjunction with the territorial spread of great political empires. In such cases of imperial conquest, relocation and expansion diffusion were not mutually exclusive. Relocation diffusion occurred as a small number of conquering elites came to rule an area. The language of the conqueror, implanted by relocation diffusion, often gained wider acceptance through expansion diffusion. Typically, the conqueror’s language spread hierarchically—adopted first by the more important and influential persons and by city dwellers. The diffusion of Latin with Roman conquests, and Spanish with the conquest of Latin America, occurred in this manner.

146

MIGRATION AND THE SURVIVAL OF LANGUAGE

As we have seen above, conquest can lead to the imposition of a new language and the abandonment or suppression of native tongues. However, these threatened languages may reappear and thrive in new places, as their speakers migrate for reasons of economic or cultural survival.

New York City is thought to be home to as many as 800 languages, making it the most linguistically dense place in the world. There are more speakers of Vlashki in Queens than in the Croatian mountain villages where the language originated, and a roughly equal number of Garifuna speakers in the Bronx and Brooklyn as in Honduras and Belize. These are but two of “a remarkable trove of endangered tongues that have taken root in New York” (Roberts, 2010).

How did New York City become home to such linguistic riches? These languages relocated there through the migration of their native speakers. While populations in the language source region may fall victim to ethnic conflict, disease, starvation, compulsory schooling, or merely assimilation into dominant language groups, thereby losing their ability to speak their native language, migrant speakers from these places may better manage to keep the tongue alive and well in their new homes.

147

Yet, many of these relocated languages find themselves under new pressure from the dominant English language in the United States. For this reason, the City University of New York started the Endangered Language Alliance, whose members canvass city neighborhoods in search of immigrant speakers of vulnerable languages. The speakers are videotaped, and the Alliance encourages the teaching and use of these languages. The reality, however, is that many of these languages will vanish from New York City’s linguistic landscape when the children of these immigrants cease to speak them regularly or stop teaching them to their children.

RELIGION AND LINGUISTIC MOBILITY

Cultural interaction creates situations in which language is linked to a particular religious faith or denomination, a linkage that greatly heightens cultural identity. Perhaps Arabic provides the best example of this cultural link. It spread from a core area on the Arabian Peninsula with the expansion of Islam. Had it not been for the evangelical success of the Muslims, Arabic would not have diffused so widely. The other Semitic languages also correspond to particular religious groups. Hebrew-speaking people are of the Jewish faith, and the Amharic speakers in Ethiopia tend to be Coptic, or Eastern, Christians. Indeed, we can attribute the preservation and recent revival of Hebrew to its active promotion by Jewish nationalists who believe that teaching and promoting Hebrew to diasporic Jews facilitate unity.

Certain languages have even acquired a religious status. Latin survived mainly as the ceremonial language of the Roman Catholic Church and Vatican City. In non-Arabic Muslim lands, such as Iran, where people consider themselves Persians and speak Farsi, Arabic is still used in religious ceremonies. Great religious books can also shape languages by providing them with a standard form. Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible led to the standardization of the German language, and the Qur’an is the model for written Arabic. Because they act as common points of frequent cultural reference and interaction, great religious books can also aid in the survival of languages that would otherwise become extinct. The early appearance of a hymnal and the Bible in the Welsh language aided the survival of that Celtic tongue, and Christian missionaries in diverse countries have translated the Bible into local languages, helping to preserve them. In Fiji, the appearance of the Bible in one of the 15 local dialects elevated that dialect to the dominant native language of the islands.

LANGUAGE’S SHIFTING BOUNDARIES

Dialects, as well as the language families discussed previously, reveal a vivid geography. Their boundaries—what separates them from other dialects and languages—shift over time, both spatially and in terms of what elements they contain or discard.

Geolinguists map dialects by using isoglosses, which indicate the spatial borders of individual words or pronunciations. The dialect boundaries between Latin American Spanish speakers using tú and those using vos are clearly defined in some areas, as shown in Figure 4.7. The choice of tú or vos for the second-person singular carries with it a cultural indication. Vos represents a usage closer to the original Spanish but is considered by many in the Spanish-speaking world to be rather archaic and, in fact, has died out in Spain itself. In other regions, particularly throughout Argentina, vos has long been used by the media; often, it is considered to reflect the “standard” dialect and usage for the area in which it is used. Because certain words or dialects can fall out of fashion or simply become overwhelmed by an influx of new speakers, isogloss boundaries are rarely clear or stable over time. Indeed, in Central America, the media are increasingly using vos—long used in conversation in the region—thus elevating vos to a more official status covering a larger territory. Because of this, geolinguists often disagree about how many dialects are present in an area or exactly where isogloss borders should be drawn. The language map of any place is a constantly shifting kaleidoscope.

isogloss

The border of usage of an individual word or pronunciation.

148

The dialects of American English provide another good example. At least three major dialects, corresponding to major culture regions, had developed in the eastern United States by the time of the American Revolution: the Northern, Midland, and Southern dialects (Figure 4.8). As the three subcultures expanded westward, their dialects spread and fragmented. Nevertheless, they retained much of their basic character, even beyond the Mississippi River. These culture regions have unusually stable boundaries. Even today, the “r-less” pronunciation of words such as car (“cah”) and storm (“stohm”), characteristic of the East Coast Midland regions, is readily discernible in the speech of its inhabitants.

Although we are sometimes led to believe that Americans are becoming more alike, as a national culture overwhelms regional ones, the current status of American English dialects suggests otherwise. Linguistic divergence is still under way, and dialects continue to mutate on a regional level, just as they always have. Local variations in grammar and pronunciation proliferate, confounding the proponents of standardized speech and defying the homogenizing influence of the Internet, television, and other mass media.

Shifting language boundaries involve content as well as spatial reach, and this, too, changes over time. Today, for example, some of the unique vocabulary of American English dialects is becoming old-fashioned. For instance, the term icebox, which was literally a wooden box with a compartment for ice that was utilized to cool food, was used widely throughout the United States to refer to the precursor of the refrigerator. Although the modern electric refrigerator is ubiquitous in the United States today, some people, particularly those of older generations and in the South, still use the term icebox. Many young people, by contrast, no longer pause to say the entire word refrigerator, shortening it instead to fridge.

149

As illustrated by the birth of the new word fridge, slang terms are quite common in most languages, and American English is no exception. Slang refers to words and phrases that are not a part of a standard, recognized vocabulary for a given language but are nonetheless used and understood by some or most of its speakers. Often, subcultures—for example, youth, drug dealers, and nightclub-goers—have their own slang that is used within that community but is not readily understood by nonmembers. Slang words tend to be used for a period of time and then discarded as newer terms replace them. For example, fresh, the bomb, and phat were used to refer to desirable, attractive, or fashionable things in the 1990s. Although many people today still recognize these words, a new generation of young people is much more likely to use a new set of words. Their children, in turn, will more than likely use yet another set of words. Slang illustrates another way in which American English changes over time.

slang

Words and phrases that are not part ofastandard,recognized vocabulary for a given languagebutthatare nonethelessusedand understood by some of itsspeakers.

Some African Americans speak a distinctive form of English. African American Vernacular English (AAVE) shares characteristics with the Southern dialect and also displays considerable African influence in pitch, rhythm, and tone. Some linguists understand AAVE as a creole language that grew out of a pidgin that developed on the early slave plantations and is today spoken by some African Americans. Indeed, AAVE shares many characteristics with other English creole languages worldwide. Today, it is considered a dialect, or variation, of Standard American English. It is also considered an ethnolect, a dialect spoken by an ethnic group, in this case, African Americans. The popularity of AAVE’s distinctive vocabulary and syntax among some white Americans, however, calls into question its ethnic exclusivity and serves to point out the instability of any language boundaries, including ethnic ones.

ethnolect

A dialect spoken by a particular ethnic group.

150

The grammar of AAVE is virtually uniform across the country, which has been attributed to the segregation of African American speakers or their relatively recent migration from the South (see Chapter 5). Some distinguishing characteristics of AAVE’s speech patterns include the use of double negatives (“She don’t like nothing”), omission of forms of the verb to be (“He my friend”), and nonconjugation of verbs (“She give him her paper yesterday”). There is some controversy over the place of AAVE in the U.S. educational system. Does AAVE constitute a distinctive language, rather than simply a dialect of English? Should it be taught—with its attendant grammar, structure, and literature—to American schoolchildren? Are those who speak AAVE and Standard English technically bilingual? This has led some linguists to refer to AAVE as African American Language (AAL), indicating the status of a separate language.

In the United States today, many descendants of Spanish speakers have adapted their speech to include words and variants of words in both Spanish and English, in a dialect known as “Spanglish” (see Seeing Geography). Although acceptance of AAVE and Spanglish as legitimate language forms is hardly without conflict (see Patricia’s Notebook and Subject to Debate), they illustrate the fluidity of languages and how they are constantly evolving and changing as the needs and experiences of their users change.