MOBILITY

5.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Define the different types of migration.

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, it is often through migration that a group formerly in the majority becomes, in a new land, different from the mainstream and thus labeled as ethnic or racialized. The many motives for mobility can have different results in terms of where a group chooses to go, which parts of its original culture relocate and which do not, and who may become its neighbors in its new home.

MIGRATION AND ETHNICITY

National Geographie’s Genographic Project uses DNA samples from volunteers worldwide to substantiate the claim that all humans descended from a group of Africans who began to migrate out of Africa about 60,000 years ago. The contemporary global pattern of ethnic populations can be traced to their specific journeys. Thus, much of the ethnic pattern in many parts of the world is the result of migration. The migration process itself often creates ethnicity, as people leave places where they belonged to a nonethnic majority and become a minority in a new home. Voluntary migrations have produced much of the ethnic diversity in the United States and Canada, and the involuntary migration of political and economic refugees has always been an important factor in ethnicity worldwide and is becoming ever more so in North America.

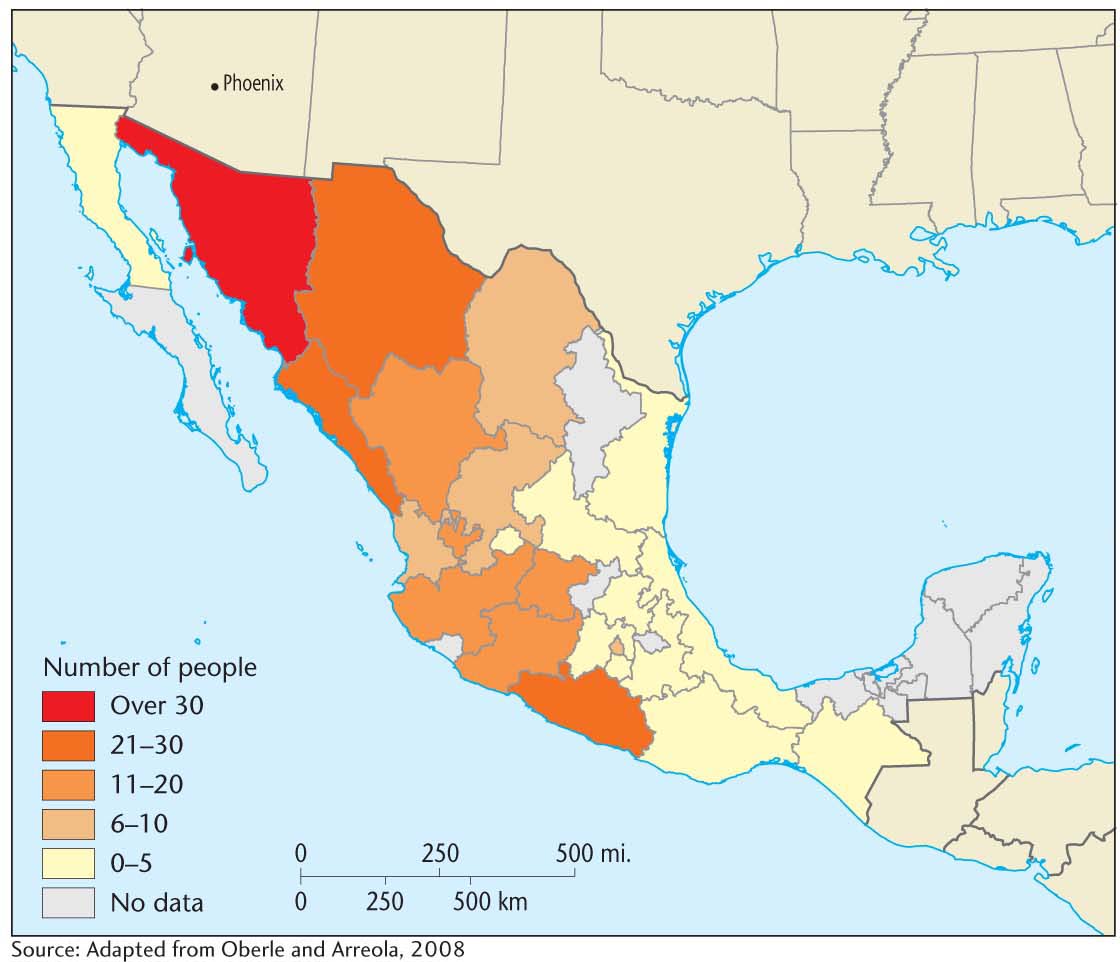

Chain migration may be involved in relocation diffusion. In chain migration, an individual or small group decides to migrate to a foreign country. This decision typically arises from negative conditions in the home area, such as political persecution or lack of employment, and the perception of better conditions in the receiving country. Often ties between the sending and receiving areas are preexisting, such as those formed when military bases of receiving countries are established in sending countries. The first emigrants, or “innovators,” may be natural leaders who influence others, particularly friends and relatives, to accompany them in the migration. The word spreads to nearby communities, and soon a sizable migration is under way from a fairly small district in the source country to a comparably small area or neighborhood in the destination country (Figure 5.15). In village after village, the first emigrants often rank high in the local social order, so that hierarchical diffusion also occurs. That is, the decision to migrate spreads by a mixture of hierarchical and contagious diffusion, whereas the actual migration itself represents relocation diffusion. This type of ethnic migration is also channelized. Channelization is a process whereby a specific source region becomes linked to a particular destination, so that neighbors in the old place became neighbors in the new place as well.

chain migration

The tendency of people to migrate along routes, over a period of time, from specific source areas to specific destinations.

channelization

A process whereby a specific source region becomes linked to a particular destination, so that neighbors in the old place became neighbors in the new place as well.

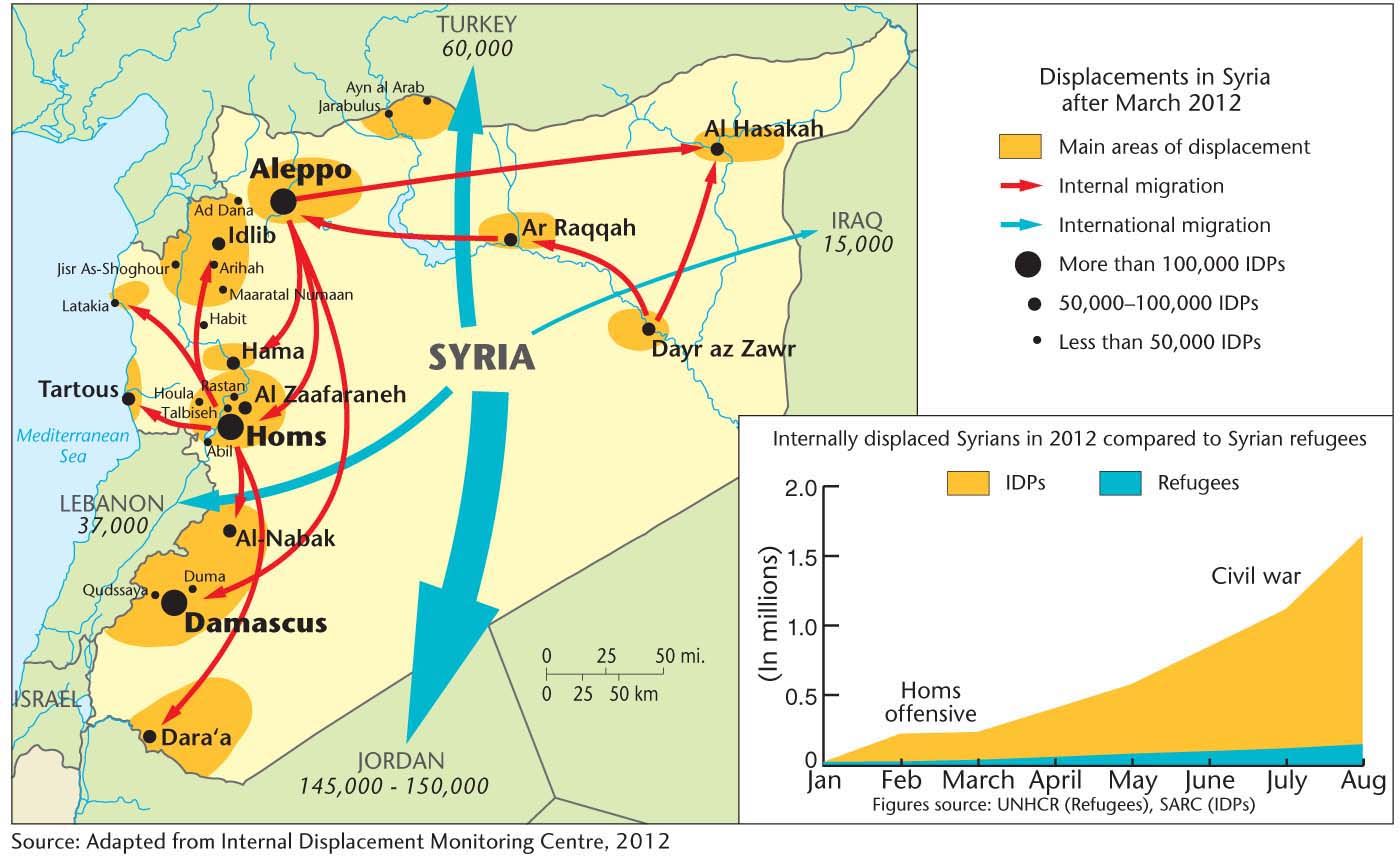

Involuntary migration also contributes to ethnic diffusion and the formation of ethnic culture regions. African slavery constituted the most demographically significant involuntary migration in human history (see the World Heritage Site) and has strongly shaped the ethnic mosaic of the Americas. Refugees from Cambodia and Vietnam created ethnic groups in North America, as did Guatemalans and Salvadorans fleeing political repression in Central America. Following forced migration and initial resettlement, the relocated group often engages in voluntary migration to concentrate in some new locality. Cuban political refugees, scattered widely throughout the United States in the 1960s, reconvened in south Florida, and Vietnamese refugees continue to gather in Southern California, Louisiana, and Texas. This is an example of step migration whereby a group proceeds to its final destination via a series of intermediate migrations. Outright warfare can also displace populations, both within the country as internally displaced persons (IDPs) and beyond its borders, as refugees. Syria presents a recent example, with internally displaced persons far outnumbering Syrian refugees fleeing the country’s borders (Figure 5.16).

Involuntary migration

Also called forced migration, refers to the forced displacement of a population, whether by government policy (such as a resettlement program), warfare or other violence, ethnic cleansing, disease, natural disaster, or enslavement.

step migration

A process by which a group proceeds to its final destination via a series of intermediate migrations.

internally displaced persons

Persons or groups that have been forced to flee their homes due to conflict, natural disaster, or persecution but who remain within the borders of their home country.

refugees

Persons or groups that have been forced to flee their home country due to conflict, natural disaster, or persecution.

196

Often, such involuntary migrations may result from policies of ethnic cleansing, whereby countries expel or massacre minorities in an attempt to produce cultural homogeneity in their populations. In addition, the culturally important sites of the targeted group, such as houses of worship, graveyards, and homes, are destroyed or desecrated. Notable past ethnic cleansings include Spain’s expulsion of its Sephardic Jewish population in 1492, several forced removals of Native Americans to reservations in the United States over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the murder or expulsion of 1.5 million Kosovar Albanians by the Serbian ethnic majority in the Balkans in the first half of the 1990s.

ethnic cleansing

The removal of unwanted ethnic minority populations from a nation-state through mass killing, deportation, or imprisonment.

Return migration represents another type of ethnic mobility and involves the voluntary movement of a group back to its ancestral homeland or native country. The large-scale return since 1975 of African Americans from the cities of the northern and western United States to the Black Belt ethnic homeland in the South is one of the most notable such movements now under way. The 2010 census found that, thanks to migration from cities like Los Angeles and Philadelphia, the South is home to 57 percent of the black population. This proportion is higher than that at any time in the preceding 50 years. Black Americans are returning to the South, particularly to cities like Atlanta, because of greater economic opportunities there than elsewhere in the country. Cultural factors play a role as well, particularly the historic attachment to place and the perception that racial prejudice has lessened in the region. Return migration has recently revitalized the once-moribund Black homeland (see Figure 5.6).

return migration

A type of ethnic diffusion that involves the voluntary movement of a group of migrants back to their ancestral or native country or homeland.

197

SIMPLIFICATION AND ISOLATION

When groups migrate and become ethnic in a new land, they have, in theory at least, the potential to introduce the totality of their culture by relocation diffusion. Conceivably, they could reestablish every facet of their traditional way of life in the area where they settle. However, ethnic immigrants never successfully introduce the totality of their culture. Rather, profound cultural simplification occurs. This happens, in part, because of chain migration: only localized fragments of a national culture diffuse overseas, borne by groups from particular places migrating in particular eras. In other words, some simplification occurs at the point of departure. Moreover, far more cultural traits are implanted in the new home than actually survive. Only selected traits are successfully introduced, and others undergo considerable modification before becoming established in the new homeland. In other words, absorbing barriers prevent the diffusion of many traits, and permeable barriers cause changes in many other traits, greatly simplifying the migrant cultures. In addition, choices that did not exist in the old home become available to immigrant ethnic groups. They can borrow novel ways from those they encounter in the new land, invent new techniques better suited to the adopted place, or modify existing approaches as they see fit. Most immigrant ethnic groups resort to all these devices to varying degrees.

cultural simplification

The process by which immigrant ethnic groups lose certain aspects of their traditional culture in the process of settling overseas, creating a new culture that is less complex than the old.

198

200

The displacement of a group and its relocation to a new homeland can have widely differing results. The degree of isolation an ethnic group experiences in a new home helps determine whether traditional traits will be retained, modified, abandoned, or even adopted by the host culture. If the new settlement area is remote and contacts with outsiders are few, diffusion of traits from the sending area is more likely. Because contacts with groups in the receiving area are rare, little borrowing of traits can occur. Isolated ethnic groups often preserve in archaic form cultural elements that disappear from their ancestral country; that is, they may, in some respects, change less than their kinfolk back in the mother country.

Language and dialects offer some good examples of this preservation of the archaic. Germans living in ethnic islands in the Balkan region of southeastern Europe preserve archaic South German dialects better than do Germans living in Germany itself, and some medieval elements survive in the Spanish spoken in the Hispano homeland of New Mexico. The highland location of Taiwanese aboriginal peoples helped maintain their archaic Formosan language, belonging to the Austronesian family, despite attempts by Chinese conquerors to acculturate them to the Han Chinese culture and language.

World Heritage Site: Island of Gorée

World Heritage Site

Island of Gorée

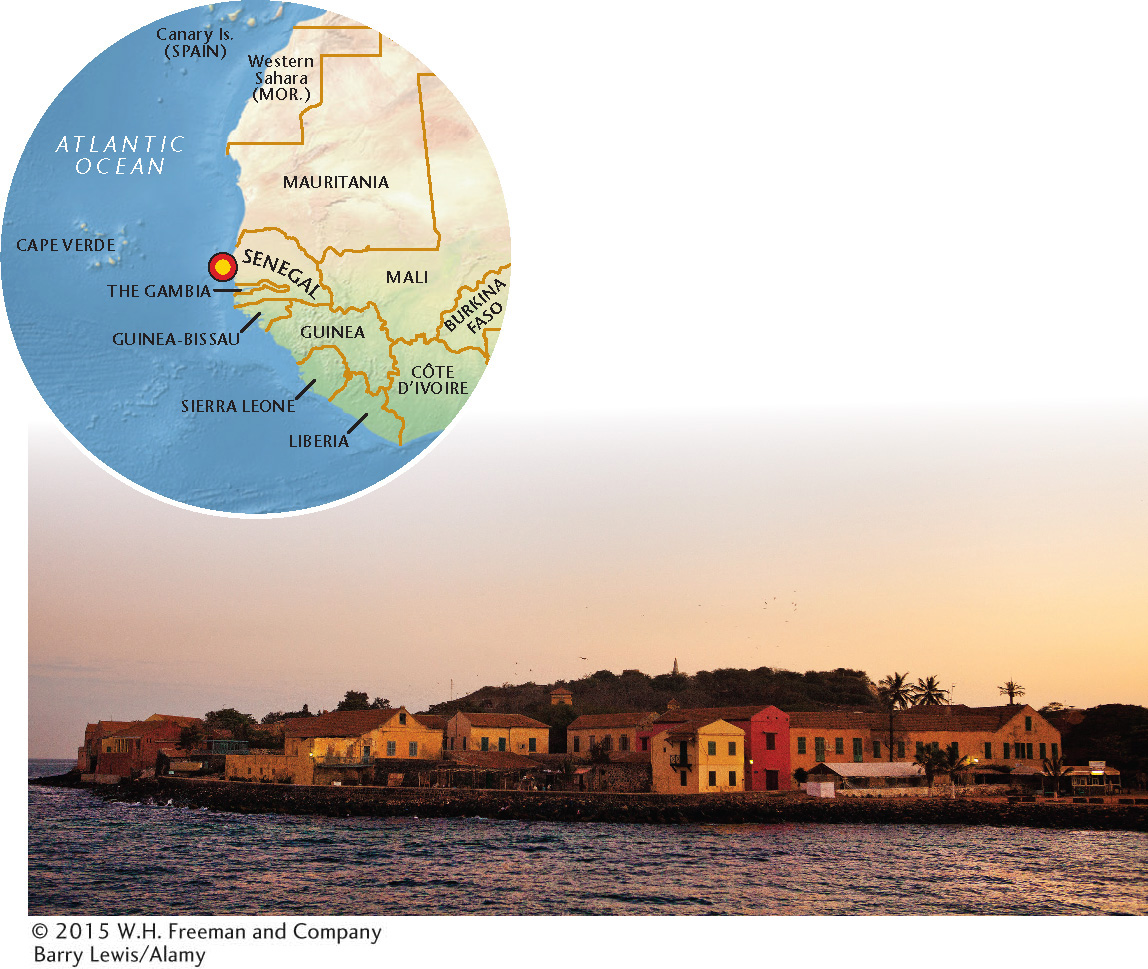

The small island of Gorée is located just 2 miles off the coast of Dakar, the capital city of Senegal. The island is positioned midway between the northern and southern tips of the west African coast, which made it centrally located for the slave trade funneling in from the west African interior. As UNESCO notes, “Gorée owes its singular destiny to the extreme centrality of its geographic positioning.” The island was used as a stopover point by Europeans on the long sea voyage down the west African coast and as a warehouse for slaves. It was claimed by the Portuguese, the Dutch, the English, and the French.

◼ Mobility is a central dimension of the slave trade. Eleven million enslaved Africans are estimated to have crossed the ocean over the three centuries encompassing the trans-Atlantic slave trade, from the 1500s to the 1800s, on their way to European colonies in the Americas.

◼ The island is a site of both painful historical memories and reconciliation. Much as with Holocaust memorials, Gorée Island is preserved and visited in order that humankind not forget the human rights atrocity that was African slavery.

◼ The island is home to three museums, a seventeenth-century police station, a castle, a small beach, and colonial houses.

◼ Though debates persist about Gorée Island’s historical significance in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, it has become a symbolically important site of remembrance, particularly for African diaspora populations.

◼ The House of Slaves, with its Door of No Return, is a museum visited by over 200,000 tourists annually.

◼ Gorée Island was declared a World Heritage Site in 1978; before that, the colonial government of Senegal had declared it a National History Site in 1944.

199

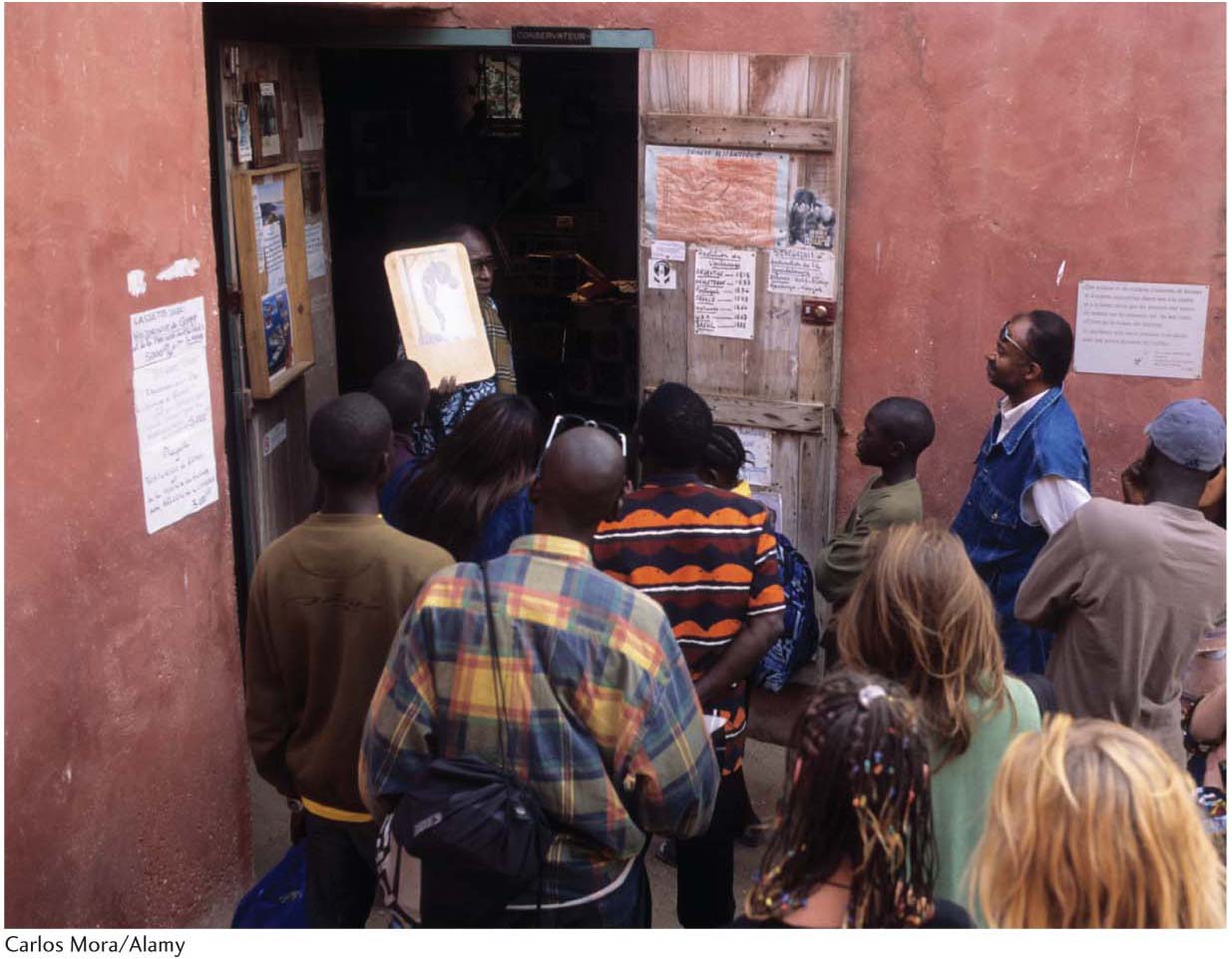

THE HOUSE OF SLAVES: Built in the 1770s, this house later belonged to a Senegalese métis (mixed-ancestry) woman, Anna Colas Pépin. Scholars believe that though she may have sold small numbers of slaves and kept domestic slaves herself, the actual slave transshipment site was not the house itself, but a location nearby. The house was restored and opened as a museum in 1962. Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye oversaw and curated the museum for 40 years, until his death in 2009.

◼ The Door of No Return. The corridor ending in a gate opening onto a wharf from which slave ships departed was known as “the trip from which no one returned.” Ndiaye claimed that a total of over 1 million African slaves made their final exit through the doors of this house over the four centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

◼ Some scholars have contested these numbers, claiming that they were, in fact, much smaller, and that Gorée itself was not central to the Senegalese slave trade. This controversy notwithstanding, the island is hugely symbolic and therefore remains meaningful to many.

TOURISM: Gorée Island attracts so-called heritage tourists, who can be defined as people looking for significant traces of their own past. Indeed, UNESCO refers to it as a “memory island.”

◼ Gorée Island is a pilgrimage site (see also Chapter 7) for the global African diaspora. Approximately 200,000 tourists visit the House of Slaves annually.

◼ Most visitors to Gorée Island, whether or not they identify as descendants of African slaves, report being extremely moved by their visit.

◼ The island’s only real source of income is tourism, which supports the fewer than 1500 local residents.

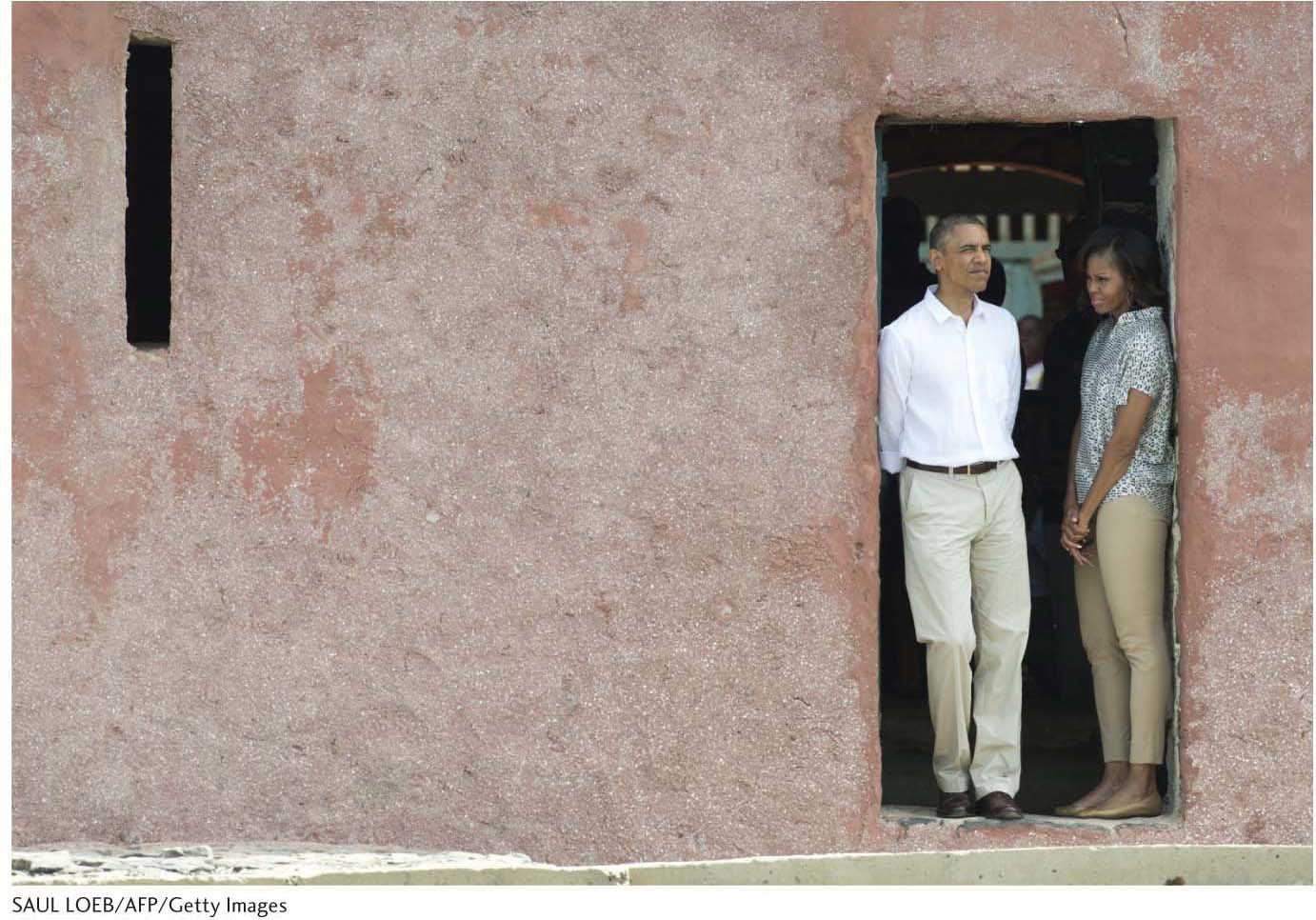

◼ Because of Gorée Island’s historical significance, it has been visited by presidents, prime ministers, and even the pope himself. The Door of No Return is a popular framing for photographs.