REGION

6.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify the importance of region to political geography.

The theme of region is essential to the study of political geography because an array of both formal and functional political regions exists. Among these, the most important and influential is the state.

state

A centralized authority that enforces a single political, economic, and legal system within its territorial boundaries. Often used synonymously with “country.”

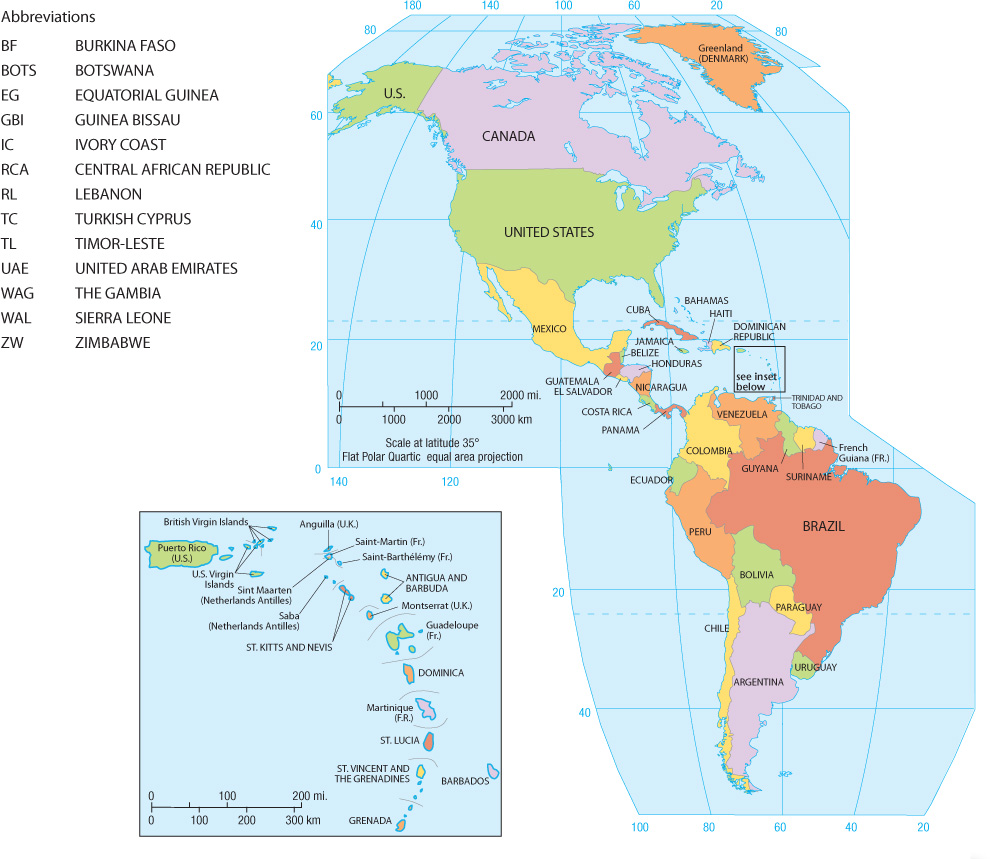

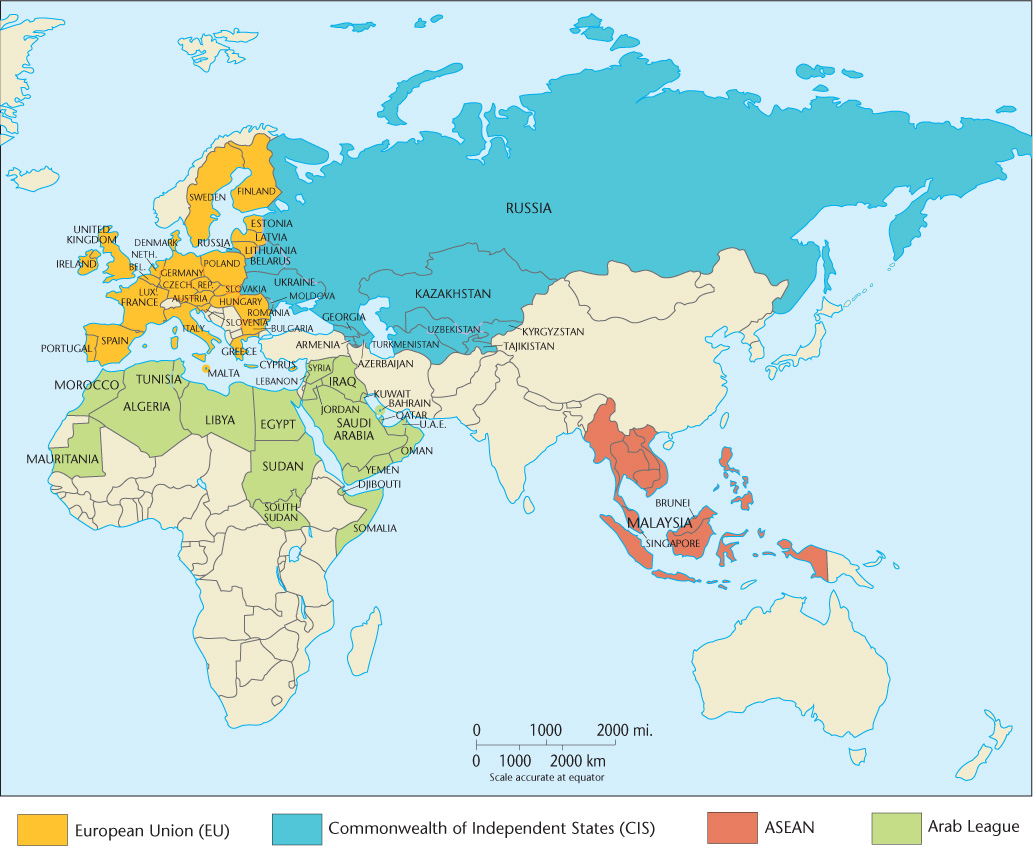

A WORLD OF STATES

The fundamental political-geographical fact is that Earth is divided into roughly 200 independent countries or states, creating a diverse mosaic of functional regions (Figure 6.1). The state is a political institution that has taken a variety of forms over the centuries, ranging from Greek city-states, to Chinese dynastic states, to European feudal states. When we talk about states today, however, we mean something very specific and historically recent. States are independent political units with a centralized authority thatmakes claims to sole jurisdiction over a bounded territory. Within that territory, the central authority controls and enforces a single system of political and legal institutions. Importantly, in the modern international system, states recognize each other’s sovereignty. That is, virtually every state recognizes every other state’s right to exist and control its own affairs within its territorial boundaries.

sovereignty

The right of individual states to control political and economic affairs within their territorial boundaries without external interference.

224

Closer inspection of Figure 6.1 reveals that some parts of the world are fragmented into many different states, whereas others exhibit much greater unity. The United States occupies about the same amount of territory as Europe, but the latter is divided into 47 independent countries. The continent of Australia is politically united, whereas South America has 12 independent entities and Africa has 55.

The modern state is a tangible geographical expression of one of the most common human tendencies: the need to belong to a larger group that controls its own piece of Earth, its own territory. So universal is this trait that scholars coined the term territoriality to describe it. Most geographers view territoriality as a learned cultural response. Robert Sack, for example, regards territoriality as a cultural strategy that uses power to control an area and communicate that control, thereby subjugating the inhabitants and acquiring resources. He argues, for instance, that the precise marking of borders is a practice originally unique to modern Western culture. The modern territorial state, he claims, emerged rather recently in sixteenth-century Europe and diffused around the globe through European colonialism.

territoriality

A learned cultural response, rooted in European history, that produced the external bounding and internal territorial organization characteristic of modern states.

colonialism

The building and maintaining of colonies in one territory by people based elsewhere.

225

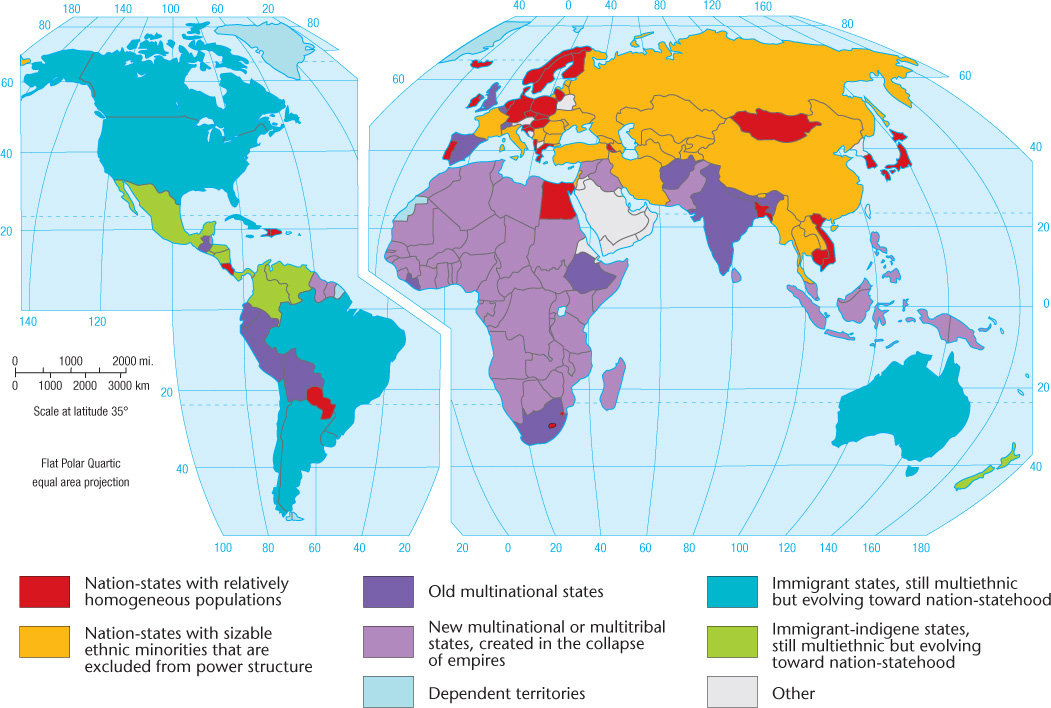

Political territoriality, then, is a thoroughly cultural-geographical phenomenon. The sense of collective identity that we call nationalism springs from a learned or acquired attachment to region and place. Nationalism is the idea that the individual derives a significant part of his or her social identity from a sense of belonging to a nation. We can trace the origins of modern nationalism to the late eighteenth century and the emergence of the nation-state. The nation-state was proposed as the ideal political geographical unit where the geographic boundaries of a nation (a people and its culture) would be identical to the territorial boundaries of the state. Nationality is culturally based in the nation-state, and the country’s raison d'être lies in that cultural identity. The more the people have in common culturally, the more stable and potent is the resultant nationalism. Examples of modern nation-states include Germany, Sweden, Japan, Greece, Armenia, and Finland (Figure 6.2). Geography and identity are thus tightly linked in the concepts of nationalism and the nation-state.

nationalism

The sense of belonging to and self-identifying with a national culture.

nation-state

An independent country dominated by a retatively homogeneous cultural groep.

226

Distribution of National Territory An important geographical aspect of the modern state is the shape and configuration of the national territory. Theoretically, the more compact the territory, the easier is national governance. Circular or hexagonal forms maximize compactness, allow short communication lines, and minimize the amount of border to be defended. Of course, no country actually enjoys this ideal degree of compactness, although some—such as France and Brazil—come close (Figure 6.3).

227

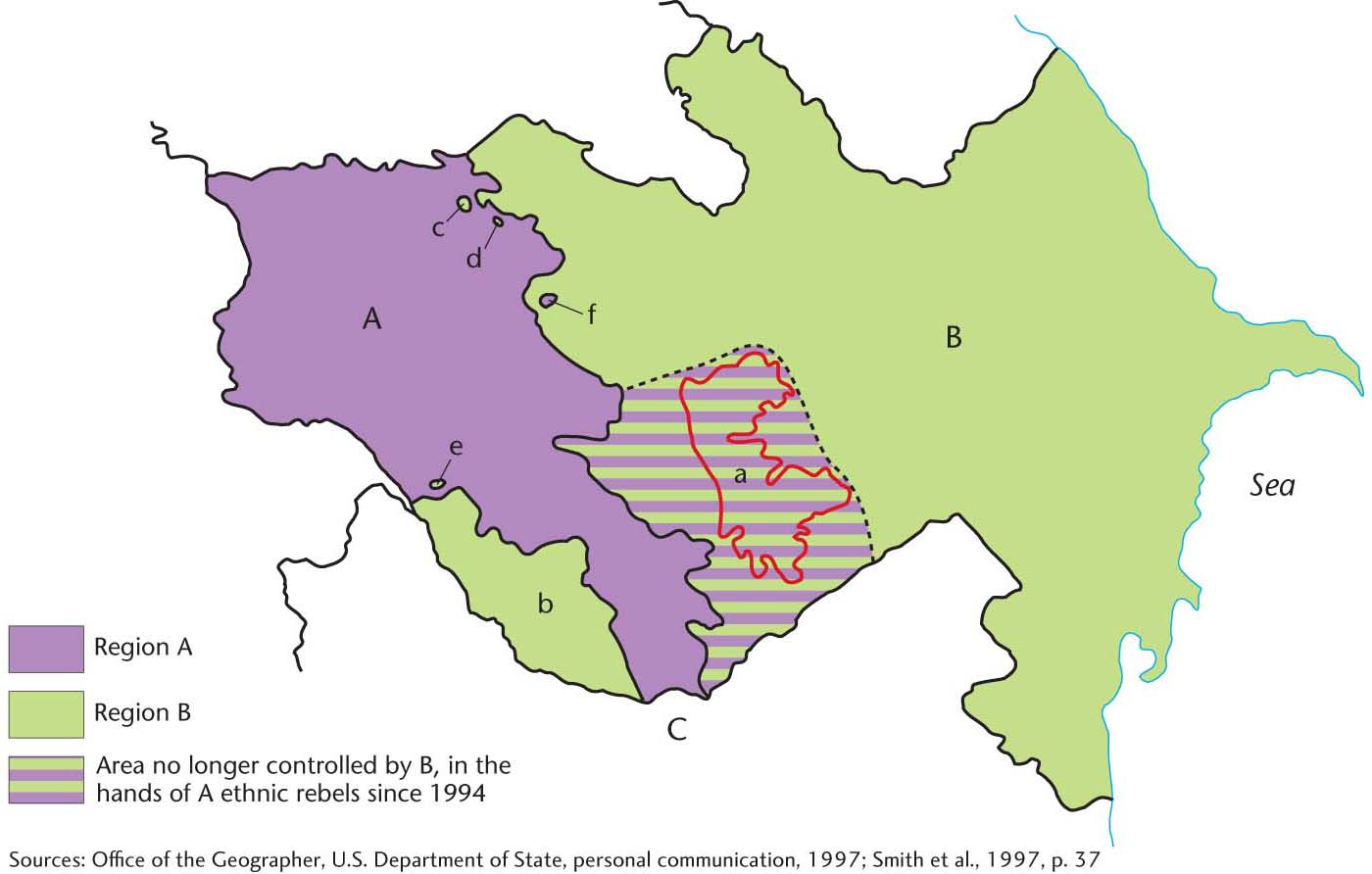

Any one of several unfavorable territorial distributions can inhibit national cohesiveness. Potentially most damaging to a country’s stability are enclaves and exclaves. An enclave is a district surrounded by a country but not ruled by it. Enclaves can be either self-governing (e.g., Lesotho in Figure 6.3) or an exclave of another country. In either case, its presence can pose problems for the surrounding country. Potentially just as disruptive is the pene-enclave, an intrusive piece of territory with only the smallest of outlets (e.g., The Gambia in Figure 6.3).

enclave

A piece of territory surrounded by, but not part of, a country.

Exclaves are parts of a national territory separated from the main body of the country to which they belong by the territory of another (e.g., Russia’s Baltic seaport, Kaliningrad in Figure 6.3; Figure 6.4). Exclaves are particularly undesirable if a hostile power holds the intervening teeritory because defense of such an isolated area is diffkult and makes substanüal demandes on national resources. Moreover, an exclave’s inhabitants, isolated from their compatriots, may develop separatist feelings, thereby causing additional problems. Pakistan provides a good example of the national instability created by exclaves. Pakistan was created in 1947 as two main bodies of territory separated from each other by almost 1000 miles (1600 kilometers) of territory in northern India. West Pakistan held the capital and most of the territory, but East Pakistan was home to most of the people. West Pakistan hoarded the country’s wealth, exploiting East Pakistan’s resources but giving little in return. Ethnic differences between the peoples of the two sectors further complicated matters. In 1971, a quarter of a century after its founding, Pakistan broke apart. The distant exclave seceded and became the independent country of Bangladesh (see Figure 6.1). Even when a national territory is geographically united, instability can develop if the shape of the state is awkward. Narrow, elongated countries, such as Chile, The Gambia, and Norway, can be difficult to administer, as can nations consisting of separate islands (see Figure 6.1 and Figure 6.3). In these situations, transportation and communications are difficult, causing administrative problems. Several major secession movements have challenged the multi-island country of Indonesia; one of these—in East Timor—succeeded in 2002 in creating the first new sovereign state of the twenty-first century (see Figure 6.1). Similarly, the island nations of Japan, Mauritius, Comoros, and Philippines have all faced separatist movements in recent years (see Figure 6.1).

exclave

A piece of national territory separated from the main body of a country by the territory of another country.

228

229

The shape and configuration of a country can make it harder or easier to administer, but they do not determine its stability. We can think of exceptions for all of the territorial forms in Figure 6.3. For example, Alaska is an exclave of the United States, but it is unlikely to produce a secessionist movement similar to the one in Bangladesh. Conversely, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria both have compact territories and both have suffered through secessionist wars. Geography is an important factor in national governance, but it is rarely the determining factor.

Boundaries Political territories have different types of boundaries. Until fairly recent times, many boundaries were not sharp, clearly defined lines but instead were referred to as zones called marchlands.

marchland

A strip of territory, traditionally one day’s march for infantry, that served as a boundary zone for independent countries in premodern times.

Today, the nearest equivalent to the marchland is the buffer state, an independent but small and weak country lying between two powerful, potentially belligerent countries. Mongolia, for example, is a buffer state between Russia and China; Nepal occupies a similar position between India and China (see Figure 6.1). If one of the neighboring countries assumes control of the buffer state, it loses much of its independence and becomes a satellite state.

buffer state

An independent but small and weak country lying between two powerful countries.

satellite state

A small, weak country dominated by one powerful neighbor to the extent that some or much of its independence is lost.

Most modern boundaries are lines rather than zones, and we can distinguish several types. Natural boundaries follow some feature of the natural landscape, such as a river or mountain ridge. Examples of natural boundaries are numerous; for example, the Pyrenees lie between Spain and France, and the Rio Grande serves as part of the border between Mexico and the United States. Ethnographic boundaries are drawn on the basis of some cultural trait, usually a particular language spoken or religion practiced. The border that divides India from predominantly Islamic Pakistan is one case. Geometric boundaries are regular, often perfectly straight lines drawn without regard for physical or cultural features of the area. The U.S.-Canada border west of the Lake of the Woods (about 93° west longitude) is a geometric boundary, as are most county, state, and province borders in the central and western United States and Canada. Not all boundaries are easily categorized; some boundaries are of mixed type, composites of two or more of the types listed.

natural boundary

A political border that follows some feature of the natural environment, such as a river or mountain ridge.

ethnographic boundary

A political boundary that follows some cultural border, such as a linguistic or religious border.

geometric boundary

A political border drawn in a regular, geometric manner, often a straight line, without regard for environmental or cultural patterns.

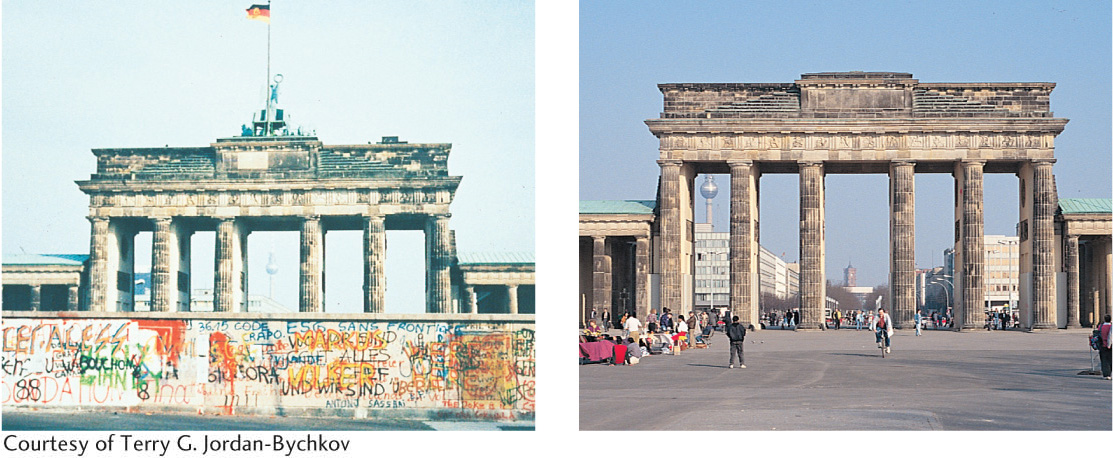

Finally, relic boundaries are those that no longer exist as international borders. Nevertheless, they often leave behind a trace in the local cultures. With the reunification of Germany in the autumn of 1990, the old Iron Curtain border between the former German Democratic Republic in the east and the Federal Republic of Germany in the west was quickly dismantled (Figure 6.5). In a remarkably short time span, measured in weeks, the Germans reopened severed transport lines and created new ones, knitting together the enlarged country. Even so, remnants and reminders of the old border remained, as it continued to function as provincial boundaries within Germany. Furthermore, it still separated two parts of the country with strikingly different levels of prosperity.

relic boundary

A former political border that no longer functions as a boundary.

Spatial Organization of Territory States differ greatly in the way their territory is organized for purposes of administration. Political geographers recognize two basic types of spatial organization: the unitary state and the federal state. In unitary countries, power is concentrated centrally, with little or no provincial authority. All major decisions come from the central government, and policies are applied uniformly throughout the national territory. France and China are unitary in structure, even though one is democratic and the other authoritarian. A federal government, by contrast, is a more geographically expressive political system. That is, it acknowledges the existence of regional cultural differences and provides the mechanism by which the various regions can perpetuate their individual characters. Power is diffused, and the central government surrenders much authority to the individual provinces. The United States, Canada, Germany, Australia, and Switzerland, though exhibiting varying degrees of federalism, provide examples. The trend in the United States has been toward a more unitary, less federal government, with fewer states’ rights. By contrast, federalism remains vital in Canada, representing an effort to counteract French Canadian demands for Québec’s independence. That is, by emphasizing federalism, the central government allows more latitude for provincial self-rule, thus reducing public support for the more radical option of secession.

unitary state

An independent state that concentrates power in the central government and grants little authority to the provinces.

federal state

An independent country that gives considerable powers and even autonomy to its constituent parts.

230

Whether federal or unitary, a country functions through some system of political subdivisions. In federal systems, these subdivisions sometimes overlap in authority, with confusing results. For example, the Native American reservations in the United States occupy a unique and ambiguous place in the federal system of political subdivisions. These semiautonomous enclaves are legally sanctioned political territories that, theoretically, only indigenous Americans can possess. In reality, ownership is often fragmented by non-Native American land holdings within the reservations. Although not completely sovereign, Native Americans do have certain rights to self-government that differ from those of surrounding local authorities. For example, many reservations can (and do) build casinos on their land even though gambling may be illegal in surrounding political jurisdictions. Reservations do not fit neatly into the American political system of states, counties, townships, precincts, and incorporated municipalities.

CENTRIFUGAL AND CENTRIPETAL FORCES

If there is one lesson to learn from the past few decades of global political geography it is that few nation-state boundaries are permanent. We have witnessed countless cycles of countries fragmenting into multiple states and scattered territories coalescing into larger political states. Many countries have, of course, remained more or less intact over the decades. Thus, we must ask, why do some countries break apart while others remain united?

231

Geographers refer to factors that promote national unity and solidarity as centripetal forces. By contrast, anything that disrupts internal order and furthers the breakup of the territory is called a centrifugal force. Many states encourage centripetal forces that help fuel nationalistic sentiment. Such factors as an official national language, national history museums, national parks and monuments, and sometimes even a national religion are actively promoted and supported by the state.

centripetal force

Any factor that supports the internal unity of a country.

centrifugal force

Any factor that disrupts the internal unity of a country.

Although physical factors such as the spatial organization of territory, degree of compactness, and type of boundaries can influence an independent country’s stability, other forces are also at work. In particular, cultural factors often make or break a country. The most viable independent countries, those least troubled by internal discord, have a strong feeling of group solidarity among their population. Strong group identity is often key to a state’s territorial integrity.

In the case of the modern state, the primary source of group identity is nationalism. Political geographer John Agnew cautions us, however, that the meaning and form of nationalism are unstable, making it difficult to generalize. One version is state nationalism, wherein the nation-state is exalted and individuals are called to sacrifice for the good of the greater whole. The twentieth-century history of state nationalism in Europe is marked by two horrific world wars in which millions of lives were sacrificed. Referring to World War I, Agnew points out that the “war itself was also the outcome of a mentality in which the individual person had to sacrifice for the good of the greater whole: the nation-state.”

When a specific ethnic group or ethnically based political party controls the state’s military, we sometimes see forced deportations and even attempted genocides in efforts to create an ethnically homogeneous national citizenry (see Chapter 5). This happened in recent decades in Rwanda in 1994 and in the Balkans through the 1990s. Most recently, the military of Sudan has been accused of attempted genocide in the Darfur region of that country (Figure 6.6). The people of Darfur are ethnically distinct from the dominant culture controlling the Sudanese state. The most notorious modern example is Nazi Germany’s attempt in the 1930s and 1940s to clear German territory of non-Germans, especially Jews and Roma (Gypsies) (see Rod’s Notebook).

Another way to create a homogeneous citizenry is through territorial fission. This happens in cases of substate nationalism, in which ethnic or linguistic minority populations seek to secede from the state or to alter state territorial boundaries to promote cultural homogeneity and political autonomy. In such cases, a smaller, more culturally homogenous country may break off from the larger state. The world’s newest nation-state, South Sudan, is a good example. We consider an array of centripetal and centrifugal forces later, in the sections on globalization and nature-culture.

territorial fission

Occurs when an ethnic or linguistic minority population seeks to secede from the state or to alter state territorial boundaries to promote cultural homogeneity and political autonomy.

POLITICAL BOUNDARIES IN CYBERSPACE

What happens to political boundaries in cyberspace? E-mail, the Internet, and the World Wide Web can cross borders in ways previously not possible, although radio, telephone, and fax machines possess some of the same border-defying qualities. In Germany, for example, Nazi and neo-Nazi propaganda is prohibited, yet the First Amendment right of freedom of speech protects the dissemination of this material in the United States. What happens when this propaganda originates in the United States and is posted electronically to online bulletin boards worldwide? Can the German government prosecute the originator of the message— an American—for violating a German law?

232

How can countries impose their laws and boundaries in the computer age? One way is to restrict citizens’ access to technological hardware such as satellite dishes, computers, phone lines, and cell phones. This is becoming increasingly difficult for even the most totalitarian regimes. Another tactic deployed by states is to allow citizens’ access to the web but to control the flow of information they receive.

The most well-known example is the deal cut between the search engine company Google and the People’s Republic of China in 2006. In order to gain access to China’s rapidly expanding market for Internet services, estimated at 162 million customers in 2007, Google agreed to create a self-censoring search engine. Its Chinese-language version was specially designed to match the Chinese government’s censorship laws. Web sites promoting ideas that the state views as threatening to its ideological dominance, such as free speech and the practice of unauthorized religions, are filtered out by Google’s search engine. Google, based in Mountain View, California, has been widely criticized in the United States for this decision and has even been called to testify before Congress about its actions. In their own defense, Google officials argue that they can do more good for China’s citizens by participating in their Internet business than by withdrawing completely.

As the Google case illustrates, states often rely on the cooperation of private service providers in their efforts to control Internet access. Twitter, an online social networking company, offers another example. In 2013 Twitter initiated a policy of compliance with state censorship laws. Beginning with Germany, Twitter began blocking a neo-Nazi group’s tweets because the country has laws restricting the promotion of Nazi ideology. While we may agree that blocking discriminatory speech is a good thing, such censorship in the United States would violate free speech rights. The Google and Twitter cases show that states still retain significant control over global information flows across borders, sometimes forcing private service providers to choose between complying with state censorship laws or being barred from doing business.

Governments often fear the power of the Internet to disseminate information that can threaten its authority. In such cases, they may take extreme action to halt information flow. In 2012, for example, China blocked its citizens’ Internet access to the New York Times when the newspaper published an article unfavorable to the country’s prime minister. During the political upheavals known as the “Arab Spring,” several Middle Eastern and North African governments tried to limit the role of the Internet in antigovernment organizing. Egypt, Libya, and Syria severed their countries’ Internet connections completely, while in Tunisia and Saudi Arabia governments used Internet censorship and surveillance to control information flow (Figure 6.7).

These cases illustrate that political boundaries are far from irrelevant in the age of the Internet. The Internet is, to a degree, eroding political boundaries by allowing information and ideas to diffuse more rapidly and completely. As a result, political barriers to cultural diffusion have become more fragile. However, countries still have some power to control what ideas are allowed inside their territorial boundaries.

233

SUPRANATIONAL POLITICAL BODIES

In addition to independent countries and their governmental subdivisions, the third major type of political functional region is the supranational organization (Figure 6.8). Supranationalism exists when countries voluntarily give up some portion of their sovereignty to gain the advantages of a closer political, economic, and cultural association with their neighbors. Sometimes supranational organizations take the form of regional trading blocs, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, which comprises Canada, the United States, and Mexico), that promote the freer flow of goods and services across international borders.

supranational organization

A group of independent countries joined together for purposes of mutual interest.

supranationalism

A situation that occurs when states willingly relinquish some degree of sovereignty in order to gain the benefits of belonging to a larger political-economic entity.

regional trading blocs

Agreements made among geographically proximate countries that reduce trade barriers so the nations will be better able to compete with other regional markets.

234

235

In the twentieth century, supranational organizations grew in numbers and importance, coincident with and counterbalancing the proliferation of independent countries. Some represent the vestiges of collapsed empires, such as the British Commonwealth, French Community, and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)—the latter a shadow of the former Soviet Union. Most supranationals, such as the Arab League or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), possess little cohesion.

The European Union, or EU, is by far the most powerful, ambitious, and successful supranational organization in the world (see Figure 6.8). It grew from a central core area of six countries in the 1950s to its present membership of 28. At first, the EU was merely a customs union whose purpose was to lower or remove tariffs that hindered trade, but it gradually took on more and more of a political and cultural role. An underlying motivation was to weaken the power of its member countries to the point that they could never again wage war against one another—a response to the devastation of Europe in two world wars.

The member countries have all sacrificed some of their sovereign powers to the EU administration. A single monetary currency, the euro, has been adopted by most EU members. Most international borders within the EU are now completely open, requiring no passport checks. More importantly for citizenship and national identity, the EU is standardizing a range of social norms related to the tolerance of religious and ethnic difference, human rights, and gender relations. In effect, the EU is pushing supranationalism to its logical conclusion. That is, at some future date nationalism as a focus of identity will be obsolete and people will think of themselves as European rather than as, say, Italian, or Latvian, or Polish. We will have to wait to learn whether centripetal or centrifugal forces will win out in the EU’s grand experiment.

Rod’s Notebook: Places of a Genocidal State

Rod’s Notebook

Places of a Genocidal State

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

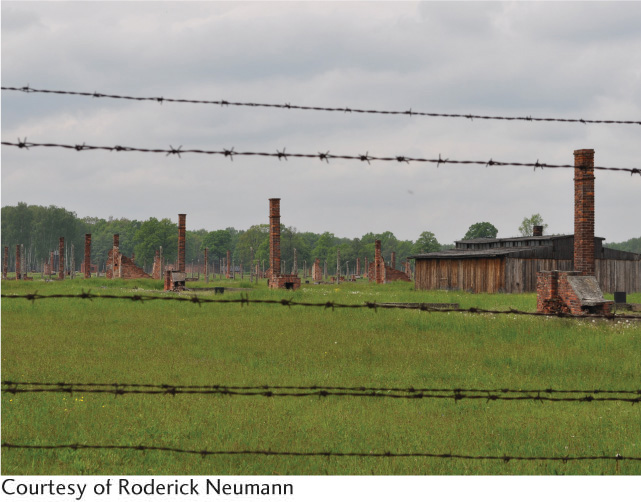

For years I have known of the Holocaust in broad historical outline. I knew that 6 million Jews were systematically murdered by the Nazi-controlled German state. The ideology of the Nazi Party was a rabid form of German nationalism founded on racial hatred, especially anti-Semitism. For Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, the “final solution” to the “problem” of European Jews was their extermination. By the 1940s, Nazi Germany had become the world’s first “genocidal state.”

Although I had long been aware of these historical events, I did not fully grasp the nature of a genocidal state and how it functioned until I traveled to Poland and visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Auschwitz-Birkenau is a Nazi death camp complex where 1.1 million people were murdered during World War II. The abstraction of 6 million murders was suddenly made concrete as I saw firsthand how the German state organized the collection of Jews from as far away as the Netherlands and Greece and brought them to this concentration camp in southern Poland. I saw how the rail lines were built to efficiently unload thousands of prisoners and quickly send them to slave labor or quick death. I saw how the Birkenau camp had been built close to manufacturing facilities of German companies in order to more efficiently exploit prisoners’ labor. Walking through the gas chambers where hundreds of thousands had died, I perceived the unspeakable horror of state-run mass murder.

I left Auschwitz-Birkenau thinking how important the experience of place is to knowledge. I could not have grasped fully the scale and magnitude of industrial mass genocide had I not looked out across the miles of rail lines and hundreds of hectares of barracks where people were stored until they could be murdered. I could never have understood how critical spatial relations were to the conduct of mass murder without physically moving through the spaces of the death camps.

I also came away realizing again how memory and place are so tightly bound. We memorialize places so that we do not forget. The United Nations declared Auschwitz-Birkenau a World Heritage Site in 1979 in hopes that the world will remember and prevent future atrocities. I know I will not forget my encounter with the places of a genocidal state.

ELECTORAL GEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS

Voting in elections creates another set of political regions. A free vote of the people on some controversial issue provides one of the purest expressions of culture, revealing attitudes on religion, ethnicity, and ideology. Geographers can devise formal culture regions based on voting patterns, giving rise to the subspecialty known as electoral geography.

electoral geography

The study of the interactions among space, place, and region and the conduct and results of elections.

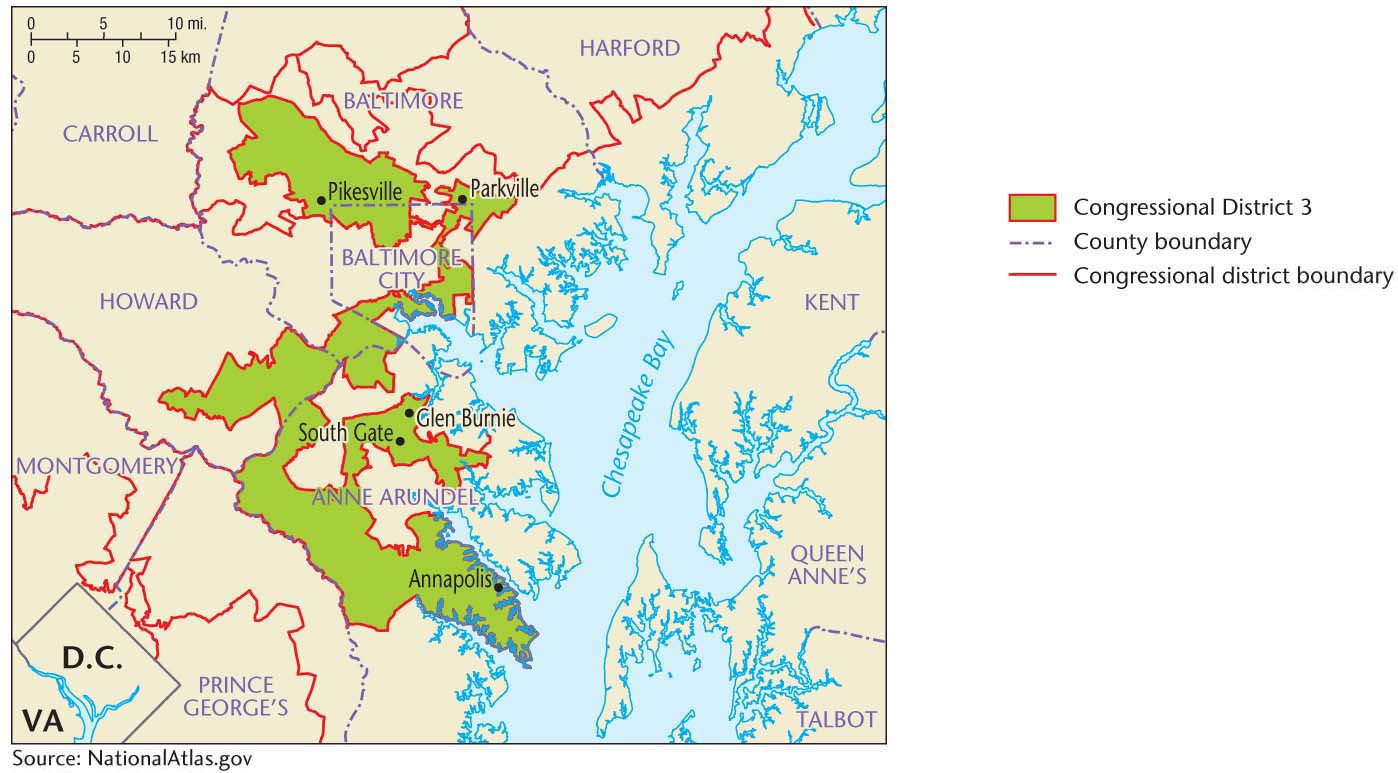

Electoral geographers also concern themselves with functional regions, in this case the voting district or precinct. Their interests are both scholarly and practical. For example, following each national census, political redistricting takes place in the United States. In redistricting, new boundaries are drawn for congressional districts to reflect the population changes since the previous census. The goal is to establish voting areas of more or less equal population and to increase or reduce the number of districts depending on the amount and direction of change in total population. These districts form the electoral basis for the U.S. House of Representatives. State legislatures are based on similar districts.

Geographers often assist in the redistricting process. Indeed, advances in GIS software make it possible to instantly draw and redraw congressional district boundaries to achieve a desired outcome. For example, Maptitude is a mapping software specially designed for professionals to use in redistricting. ProgressiveCongress.org supports the development and free distribution of software called Dave’s Redistricting application. In all such cases, redistricting software offers a way to rapidly draw congressional maps based on the latest census data.

Gerrymandering the Vote The shape of district or precinct boundaries can significantly influences election results. Boundaries can be manipulated to favor one political party over another. If redistricting remains in the hands of legislators, then the majority political party will often try to arrange the voting districts geographically to maximize and perpetuate its power. This practice is called gerrymandering and the resultant voting districts often have awkward, elongated shapes (Figure 6.9). A gerrymandered district in North Carolina was recently referred to as having the shape of a “fat squid,” while a district in Georgia was labeled a “flat-cat roadkill.”

gerrymandering

The drawing of electoral district boundaries in an awkward pattern to enhance the voting impact of one constituency at the expense of another.

236

Gerrymandering can be accomplished by one of two methods. One is to draw district boundaries so as to concentrate all of the opposition party into one district, thereby creating an unnecessarily large majority while also ensuring that it cannot win elsewhere. In the lingo of political operators, this is known as “packing.” A second method is to draw the boundaries so as to divide opposition votes into many districts. This has the effect of diluting the opposition’s vote so that it does not form a simple majority in any district. This is known as “cracking.”

Gerrymandering is nothing new. It has been a recognized, if sometimes illegal, political tactic in the United States since the early 1800s. However, recent demographic shifts, historic racial and ethnic party affiliations, and advances in redistricting software have combined to make gerrymandering an evermore common practice in the United States. Texas provides a good example. Its population grew enough to gain an additional four congressional seats after the 2010 census. Hispanics and African Americans, historic supporters of the Democratic Party, accounted for the vast majority of the population growth. The Republican Party, however, controlled the state legislature, which is responsible for redrawing district boundaries. Seventy percent of the new districts drawn by the Republican legislature had white (traditionally Republican supporters in Texas) majorities even though whites’ share of the state population dropped from 52 percent to 45 percent. Republicans consequently won an additional four districts, while minority populations (now in the majority) gained none. Because the Texas redistricting was so blatantly discriminatory toward minority populations, it was repeatedly and successfully challenged in federal courts.

237

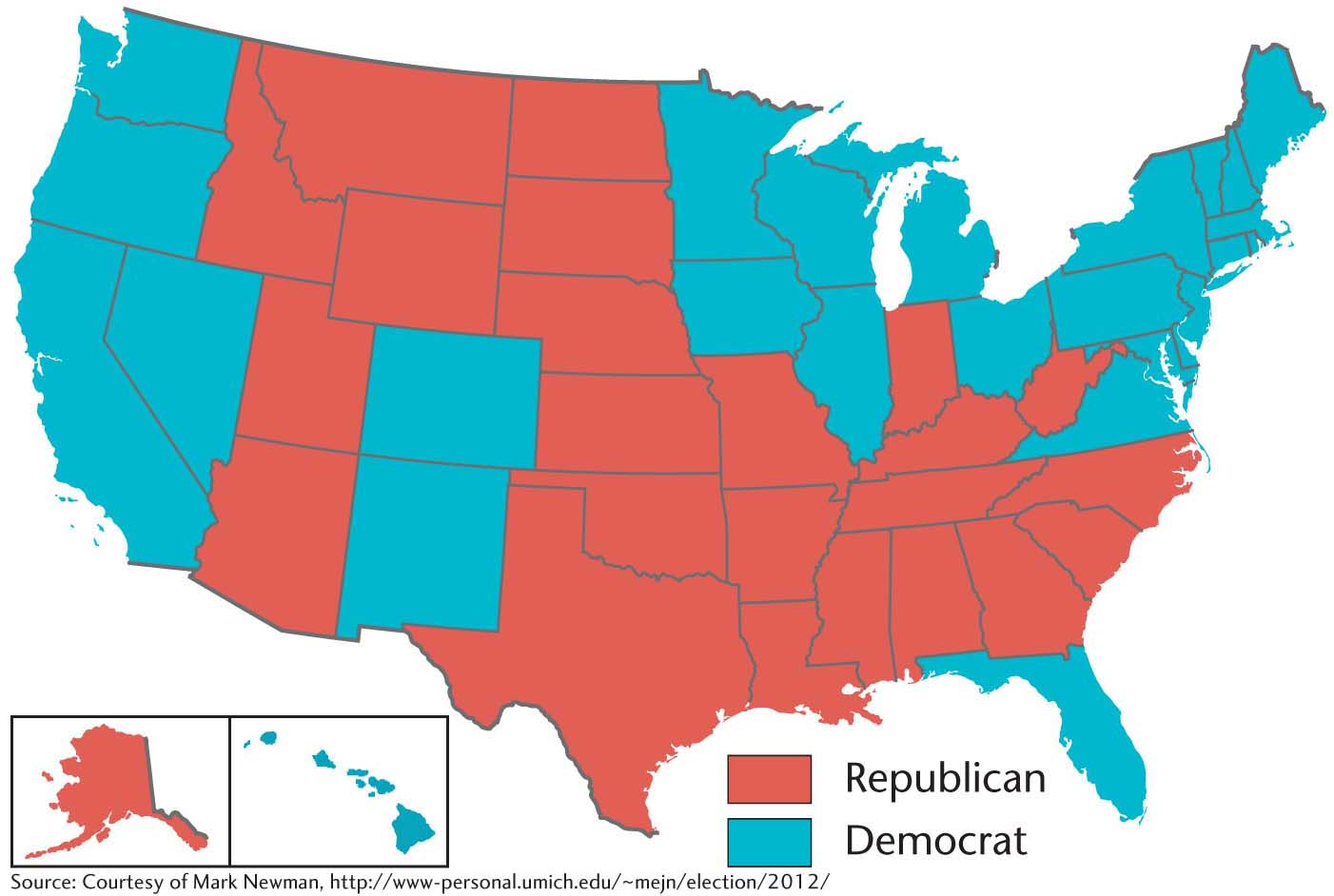

RED STATES, BLUE STATES

In recent years, various commentators in academia and the popular media have used maps of national election results to suggest that the United States is divided into distinct culture regions. We can trace this argument to the postelection analysis of the controversial 2000 presidential election, when, for the first time, news media adopted a universal color scheme for mapping voter preferences. States where the majority of voters favored the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate were assigned the color blue, whereas those favoring the Republican candidate were assigned red. When cartographers mapped the state-by-state results of the 2000 and subsequent presidential elections, the solid blocks of starkly contrasting colors gave the appearance of a deeply divided country (Figure 6.10).

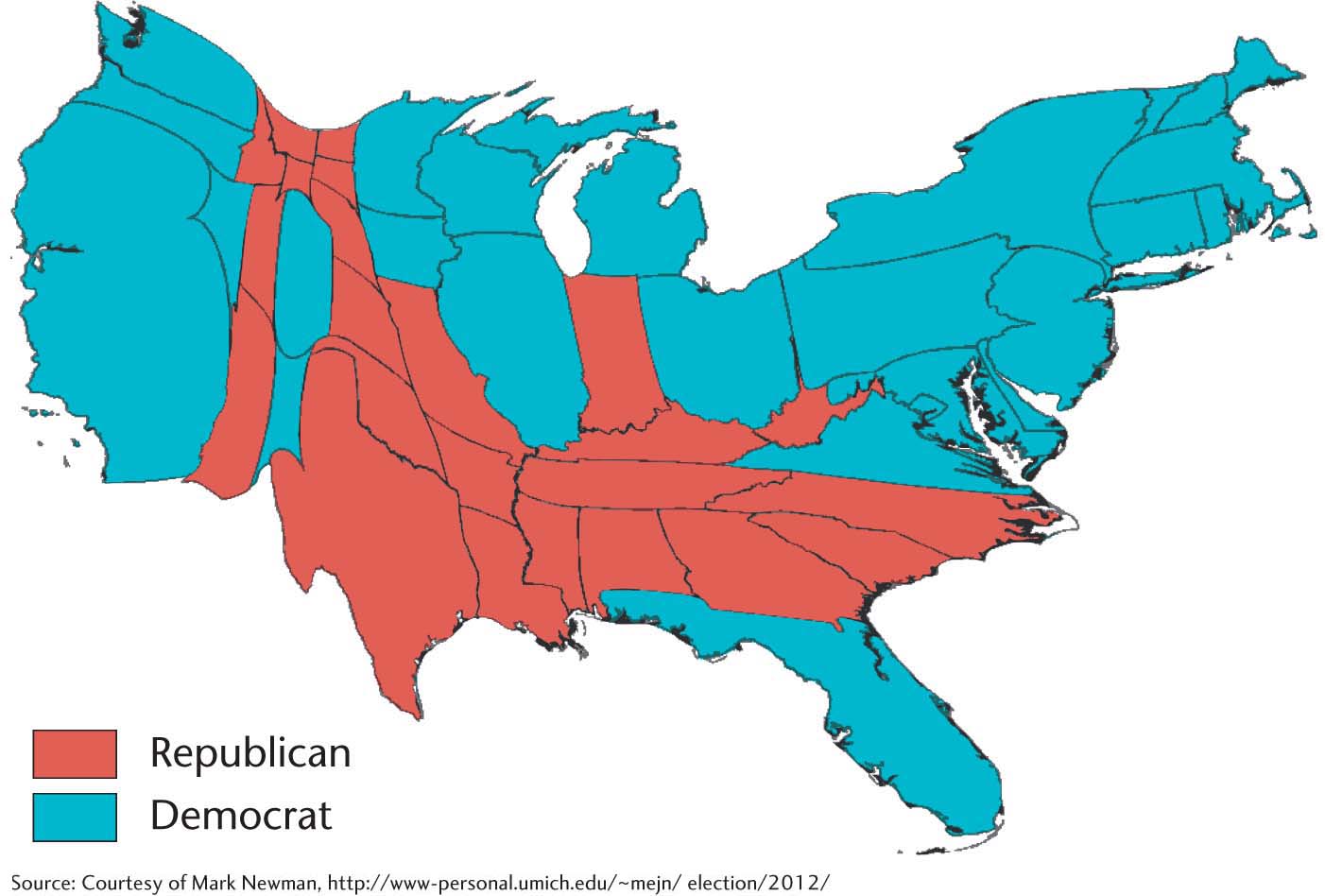

The terms red state and blue state entered the popular lexicon in reference to the division of the United States into regions of “conservative” and “liberal” cultures that these maps implied. Figure 6.10 suggests, for example, that the U.S. South is politically and culturally conservative, whereas the West Coast is liberal. These maps, so common in the popular media, are overly simplistic and, therefore, misleading. For example, the solid red coloring of a large portion of the country in Figure 6.10 implies that most of the United States is culturally and politically conservative. However, this map gives inordinate visual importance to states of larger areal extent, no matter what their population. A cartogram provides a better representation of both the true significance of states in the presidential election and the relative proportion of voters favoring Democrats or Republicans (Figure 6.11). When states’ populations are taken into account, U.S. voters look much more favorable toward Democratic rather than Republican candidates.

The red state/blue state designation also exaggerates the appearance of sharp geographic divisions within the country. Whether a state is designated “red” or “blue” is based on the winner-take-all system that the United States uses for presidential elections. That is, the candidate that receives a simple majority in the popular vote takes all the Electoral College votes for that state. George W. Bush, for example, defeated Al Gore in Florida by only 537 votes in 2000, but he received all 25 of the state’s electoral votes. This was an unusually close result, but it is common in presidential elections for only a small percentage of a state’s popular vote to separate the winner and the loser. Designating a state such as Florida as “red” thus masks the narrow margin of the Republican victory and exaggerates the existence of regional polarization.

238

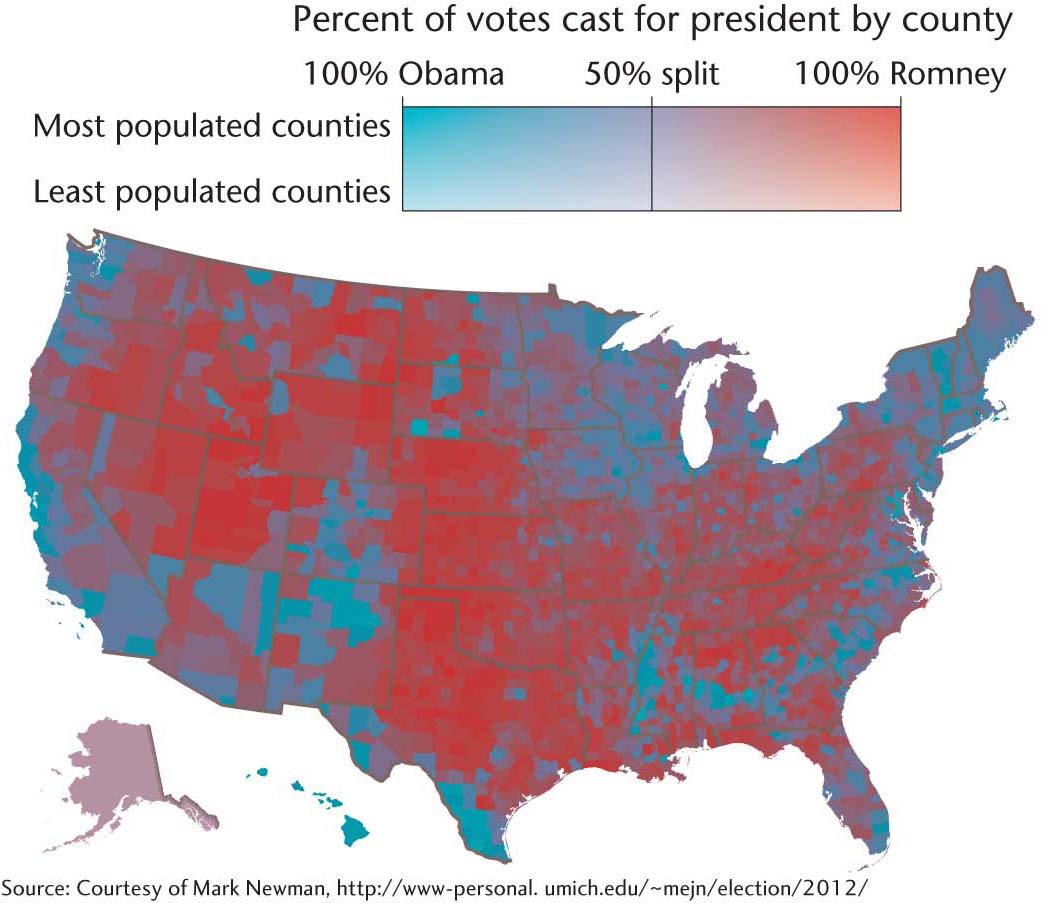

The limitations of the red state/blue state designation have led to the introduction of the term purple state to signify closely divided states. If we apply the purple state idea (i.e., shadings of color rather than stark contrasts) to county-level election results, we find that the simplistic division of the United States into liberal and conservative regions begins to break down (Figure 6.12). There is a great deal of county-by-county variation within states across the United States. New geographic patterns emerge in this map that belie the idea of large regional divisions in the country.

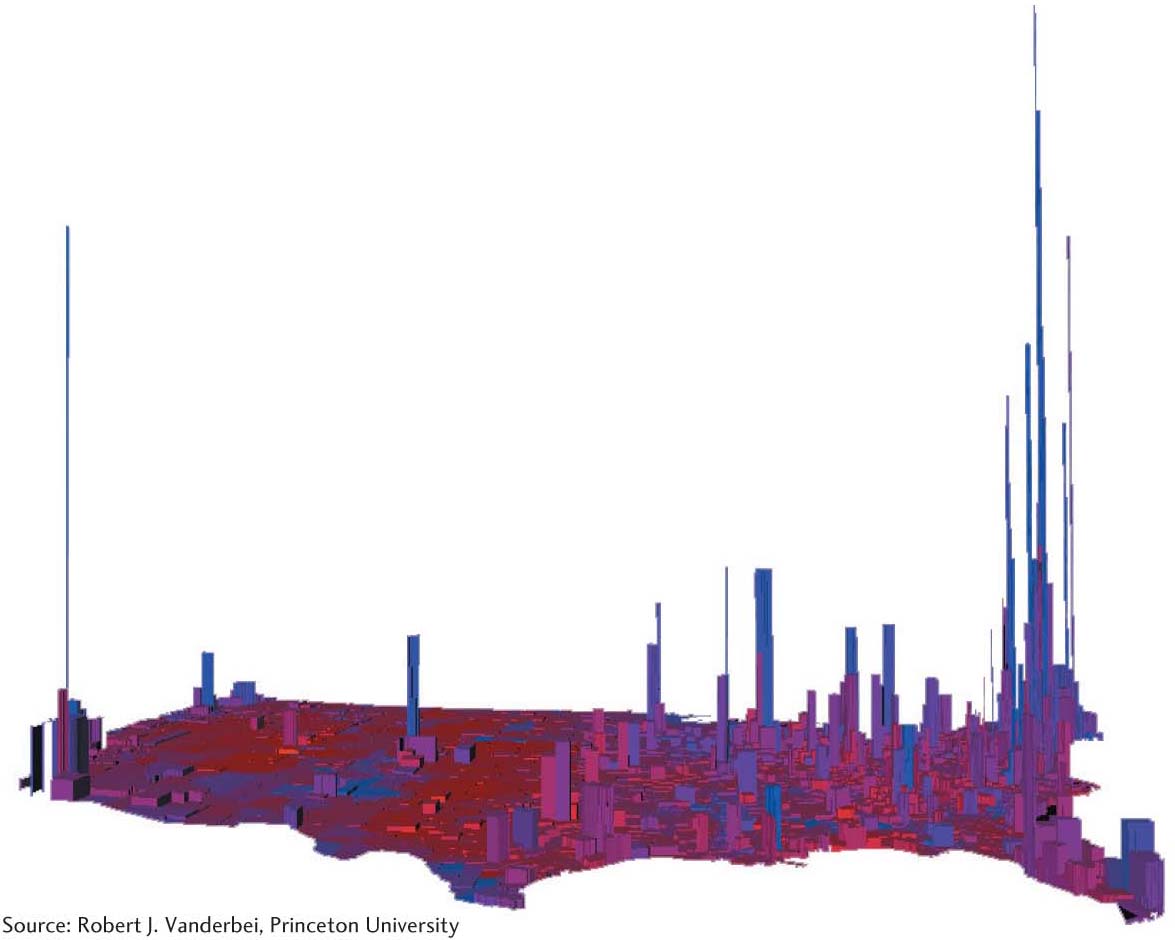

Using shades of color and county-level results— rather than using contrasting colors and state-level results—provides a very different picture of U.S. regional political and cultural differences. Even this nuanced and finely grained cartographic presentation does not reveal all of the geographic complexities of U.S. presidential elections. With three-dimensional cartographic techniques, another pattern emerges. In the map in Figure 6.13, height represents voters per square mile, so that volume represents total number of voters. Here, the core geographic difference appears to exist between cities and rural areas, not between regions. The general pattern we see is that rural areas are predominantly Republican and cities are predominantly Democratic.

A closer analysis of the red state/blue state phenomenon reveals some of the complexities involved in electoral geography. Choices about the scale at which data are aggregated, the cartographic techniques employed, and even the map colors influence the interpretation of election results. This is something to keep in mind when you evaluate claims about a divided America.

239