GLOBALIZATION

6.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe the effects of globalization on political geography.

The effects of globalization are complex. On the one hand, the idea of national self-determination continues to spread with the increase in global communications. Thus, new states continue to appear on the world map. On the other hand, the forces of globalization may be rendering some functions of the territorial state obsolete. As we will learn in this section, a great deal of speculation exists regarding the impact of globalization on political geography (see Subject to Debate).

THE NATION-STATE

As globalization has evolved, one of the most profound effects has been the division of the entire globe into nation-states. The link between global political and cultural patterns is epitomized by the nation-state, created when a nation—a people of common heritage, memories, myths, homeland, and culture; speaking the same language; and/or sharing a particular religious faith—achieves independence as a separate country.

Scholars generally trace the nation-state model to Europe and the European settler colonies in the Americas of the late eighteenth century. Political philosophers of the time argued that self-determination—the freedom to rule one’s own country—was a fundamental right of all peoples. The ideal of self-determination spread, and over the course of the nineteenth century, a globalized system of nearly 100 nation-states emerged. Many of these nation-states, such as England, Portugal, Holland, and France, ruled overseas territories as colonies of the mother country. These territories were considered imperial holdings. Thus, in colonial territories, the important boundaries were those between European empires rather than nation-states. Under European Empire, self-determination did not apply to colonies.

However, when the United Nations was created in 1945, it incorporated the principle of national self-determination into its charter. This principle was adopted by independence movements in European colonies around the globe and led ultimately to decolonization. By the end of the 1960s, most colonial empires had dissolved into dozens of new nation-states. The Soviet Union, the last great empire to fall, disintegrated into 15 sovereign nation-states in 1991. The nation-state is now the primary political-geographic form for the entire globe (see Figure 6.1).

GLOBALIZATION AND SOVEREIGNTY

Many commentators have argued in recent years that globalization is eroding the sovereignty of the nation-state. Globalization, it is said, operates in networks and flows that are less and less affected by international borders. Best-selling journalist Thomas Friedman is a leading proponent of this position. He suggests that the power of states in the global order has been greatly diminished by free trade agreements, the Internet, satellite communications, and other such developments. In addition, many economists argue that “global markets” will increasingly dictate an individual state’s social policies. That is, the global market will force states to reduce the cost of doing business so that they may remain competitive. The cumulative effect of globalizing processes, then, is a diminution of a nation-state’s control over affairs within its boundaries.

246

247

According to geographer John Agnew, the idea that globalization is diminishing the role of states is based on a misunderstanding of the history and character of state sovereignty. Agnew argues that sovereignty has been (1) mistakenly equated to territory and (2) assumed to be equally distributed among states. That is, neither the assumption that a state has total control over affairs within its territorial boundaries nor the assumption that a state’s sovereignty ends at its borders is historically accurate. These mistaken assumptions lead to an all-or-nothing view of sovereignty. Agnew suggests it is more accurate to think in terms of effective sovereignty. That, is we should give attention to the power of states to effectively enforce or ignore sovereignty claims irrespective of territorial boundaries.

effective sovereignty

The idea that states’ power to effectively enforce or ignore sovereignty claims irrespective of territorial boundaries varies in time and from country to country.

An example will help to illustrate these points. The U.S. government began holding international prisoners in a detention center in a naval base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in 2002 (Figure 6.19). The government argued that the Guantánamo center is outside of federal court jurisdiction because it is not part of U.S. territory. At the same time, the U.S. government ignored the Cuban state’s claim of sovereignty over the area and enforced sole authority within the boundaries of the naval base. In short, the United States exercised effective sovereignty over a space that is contained within Cuba’s territorial boundaries but completely outside of the U.S.’s. Sovereignty is not matched to nation-state territory in this case nor is it equally distributed between Cuba and the United States. We could present many similar examples related to international migration, Internet use, global transportation, and other such globalizing processes.

So how does Agnew’s argument help us understand globalization’s effects on state sovereignty? First, not all states will be affected by globalization in the same way and many stronger states will have a great deal of influence over the way globalization unfolds. For example, the U.S. government’s new banking regulations implemented within the country’s borders after the 2008-2009 credit crisis greatly altered the way global financial markets operate. Second, many of the challenges to sovereignty presented by globalization have always existed in some form. Globalization did not create these challenges, but has made them vastly more complicated and wide ranging. As Agnew concludes, the problem is “simply too complex for the binary thinking—globalization versus states.”

248

Subject To Debate: Whither the Nation-State?

Subject To Debate

WHITHER THE NATION-STATE?

Globalization presents powerful new challenges to the nation-state’s dominant position in political geography. Undeniably, globalization has redefined the nation-state’s role in regulating cultural, economic, and political life within its territorial boundaries. For instance, some scholars suggest that the increasing mobility of people on a global scale means that the ideal of a culturally homogeneous national identity is less and less attainable. In the economic sphere, production, trade, and finance are organized through transnational networks that operate as if national borders did not exist. Politically, the power of the nation-state is weakened by the rise of global institutions, such as the World Trade Organization, that have the power to penalize countries through trade sanctions.

There is, however, counterevidence suggesting that the nation-state is stronger than ever under globalization. In response to the greater transnational mobility of people, nationalist opposition has grown through so-called nativist movements that seek to stem the flow of immigrants at their countries’ borders. Although finance and trade operate through global networks, transnational flows remain constrained and directed by the laws and policies of nation-states. Capital investment remains solidly grounded in the legal and institutional structures of the nation-state. The international pecking order, in place for more than a century, remains intact because globalization has done little to shift the structural inequalities among nation-states. Clearly, globalization’s implications for the continued supremacy of the nation-state are complex and unresolved.

Continuing the Debate

Based on the discussion above, consider these questions:

•Is globalization a new phenomenon operating independently of the nation-state, or is it a set of processes structured by an underlying foundation of sovereign countries?

•Are the territorial barriers erected by nation-states being dissolved or reinforced by globalization?

• Under what circumstances and because of what cultural, economic, or political phenomena might globalization strengthen or weaken nation-states?

•Is a major reorganization of the world’s political geography still unfolding, with the consequences of globalization yet to be fully evident?

•What new forms of political-geographic organization might emerge to supplant the territorial nation-state?

THE CONDITION OF TRANSNATIONALITY

Transnationalism and transnationality are terms that are increasingly being heard in the halls of academia as well as in popular media. Among other things, these terms suggest that the processes of globalization are raising new questions about cultural identities. Nationality and ethnicity may continue to be important in an era of globalization, but what should one make of the increasing number of people who live, work, and play in a way that is neither rooted in a tightly knit ethnic community nor territorially grounded in the traditional nation-state? What sorts of cultural identities do these people create and defend? Is a culture of transnationalism emerging?

Geographer Katharyne Mitchell suggests that we might think about some of the cultural implications of globalization in terms of a “condition of transnationality.” She points out that the restructuring of the world economy caused by globalization has produced a great increase in the movement of people across borders. One of the key ways in which this movement differs from other historical migrations is that it tends not to be unidirectional and permanent. With the aid of new transportation and communications technologies, people are able to maintain social networks and physically move about in ways that transcend political boundaries. The experience of cultural “in-betweenness”—of living in and being linked to multiple places around the globe, while being rooted in no single place—has become fundamental to the identity of a growing group of people.

Mitchell’s study of Hong Kong Chinese immigrants in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, illustrates the idea of transnationalism. Immigrants entering the country under a law designed to attract business investment had to establish businesses based in Canada. The main immigrants taking advantage of this law were Hong Kong Chinese businesspeople leaving the colony in anticipation of its handover to the People’s Republic of China.

As it happened, these immigrants maintained business and social ties in both Hong Kong and Canada, moving freely and frequently between them. In the process, a whole set of cultural conflicts were ignited between longtime Vancouver residents and the transnational Chinese. Neighborhoods were transformed as the transnationals attempted to establish themselves economically and culturally. They rapidly bought up real estate, demolished old houses, built houses in uncharacteristic architectural styles, and redesigned residential landscaping. Their mobility—a culturally defining characteristic of transnationals—made them appear transient and rootless in the eyes of longerterm residents and weakened the legitimacy of their claims and practices. This case shows us that the cultural aspects of transnationalism are bound up with the economic and political processes of globalization.

ETHNIC SEPARATISM

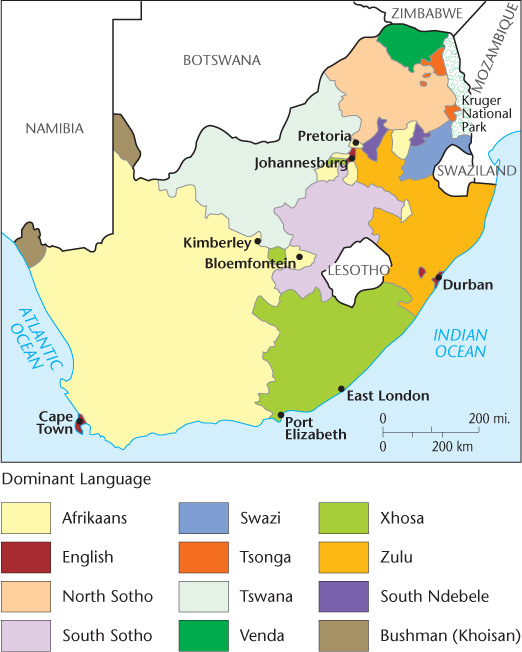

Many independent countries—the large majority, in fact—are not nation-states but instead contain multiple national, ethnic, and religious groups within their boundaries. India, Spain, and South Africa provide examples of older multiethnic countries. Figure 6.20 illustrates this point by dividing up South Africa linguistically. Many, though not all, multiethnic countries came into being in the second half of the twentieth century. These were former colonies in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia whose boundaries were a product of colonialism. European colonial powers drew political boundaries without regard to the territories of indigenous ethnic or tribal groups. These boundaries remained in place when the countries gained the right of self-determination. Although these states are often culturally diverse, they are sometimes plagued by internal ethnic conflict. What’s more, members of a single, territorially homogeneous ethnic group may find themselves divided among different states by culturally arbitrary international borders.

249

Many independent countries function as nation-states because the political power rests in the hands of a dominant, nationalistic cultural group, whereas sizable ethnic minority groups reside in the national territory as second-class citizens. This creates a centrifugal force, disrupting the country’s unity. Many of the newest nation-states carved out of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, such as Estonia, Armenia, and Serbia, are relatively linguistically and ethnically homogeneous. These states’ cultural homogeneity represents a centripetal force that supports national unity.

Globalization, particularly the establishment of rapid global communications, has encouraged once isolated and voiceless minority populations to appeal their rights of autonomy and self-determination to the global community beyond their nation-state borders. Ethnic groups and indigenous peoples are cultural minorities living in a state dominated by a culturally distinct majority. Those who inhabit ethnic homelands (see Chapter 5) often seek greater autonomy or even full independence as nation-states. Even some old and traditionally stable multinational countries have felt the effects of separatist movements, including Canada and the United Kingdom. Certain other countries discarded the unitary form of government and adopted an ethnic-based federalism, in hopes of preserving the territorial boundaries of the state. The expression of ethnic nationalism ranges from public displays of cultural identity to organized protests and armed insurgencies. Occasionally, successful secessions occur, resulting in the birth of a new nation-state.

THE CLEAVAGE MODEL

Why do so many cultural minorities seek political autonomy or independence? The cleavage model, originally developed by Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan to explain voting patterns in electoral geography, sheds light on this phenomenon. It proposes to explain persistent regional patterns in voting behavior (which, in extreme cases, can presage separatism) in terms of tensions pitting the national core area against peripheral districts, urban against rural, capitalists against workers, and the dominant culture against minority ethnic cultures. Frequently, these tensions coincide geographically: an urban core area monopolizes wealth and cultural and political power, while ethnic minorities, excluded from the power structure, reside in peripheral, largely rural, and less affluent areas.

cleavage model

A political-geographic model suggesting that persistent regional patterns in voting behavior, sometimes leading to separatism, can usually be explained in terms of tensions pitting urban against rural, core against periphery, capitalists against workers, and power group against minority culture.

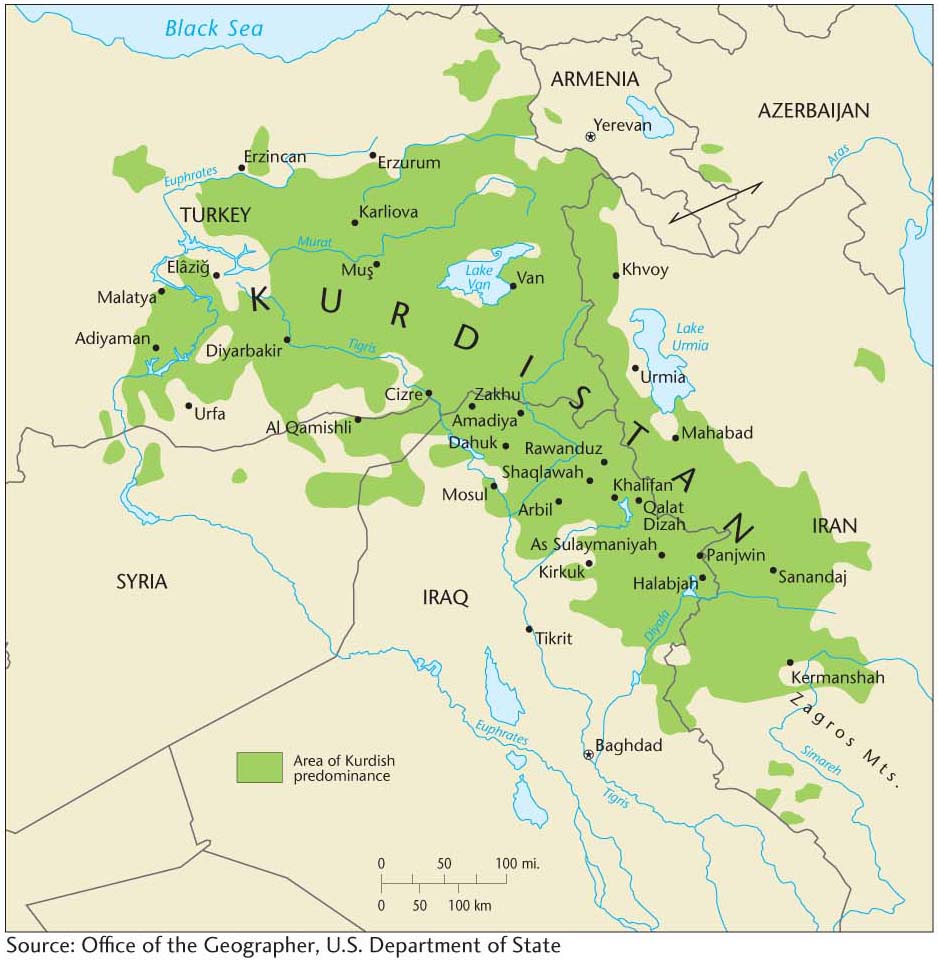

The great majority of ethnic separatist movements, particularly those that have moved beyond unrest to violence or secession, are made up of peoples living in national peripheries, away from the core area of the country. Every republic that seceded from the defunct, Russian-dominated Soviet Union lay on the borders of that former country. Similarly, the Slovenes and Croats, who withdrew from the former Yugoslavia, occupied border territories peripheral to Serbia, which contained the former national capital of Belgrade. Kurdistan is made up of the peripheral areas of Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey—the countries that currently rule the Kurdish lands (Figure 6.21). Slovakia, long poorer and more rural than Czechia (the Czech Republic) and remote from the center of power at Prague, became another secessionist ethnic periphery. In a few cases, the secessionist peripheries were actually more prosperous than the political core area, and the separatists resented the confiscation of their taxes to support the less affluent core. Slovenia and Croatia both occupied such a position in the former Yugoslavia.

250

251

By distributing power, a federalist government reduces such core-periphery tensions and decreases the appeal of separatist movements. Switzerland, which epitomizes such a country, has been able to join Germans, French, Italians, and speakers of Raeto-Romansh into a single, stable independent country. Canada developed under Francophone pressure toward a Swiss-type system, extending considerable self-rule privileges even to the Inuit and Native American groups of the north. Russia, too, has adopted a more federalist structure to accommodate the demands of ethnic minorities, and 31 ethnic republics within Russia have achieved considerable autonomy. One of these, Chechnya (called Ichkeria by its inhabitants), has been fighting for independence.

Less common than the core-periphery pattern of ethnic separatism are cases where two competing cores exist within one state. Spain is a good example. Madrid, the political capital of Spain, is culturally and economically rivaled by Barcelona, one of Europe’s largest and most vital industrial cities. Located on the northeast coast of Spain, Barcelona is the capital city of the Autonomous Community of Catalonia, home to Spain’s large ethnic Catalan minority. Residents have a native tongue, Catalan, distinct from Spain’s official language, Castilian (what English speakers call Spanish). Catalonian nationalists, active for nearly a century, have organized a major political movement for the secession of Catalonia from Spain. By turn of the twenty-first century, the movement had picked up a significant head of steam. A series of polls were conducted among Catalonian residents in 2011 and 2012, the results of which indicated small to overwhelming majorities in favor of secession and Catalonian independence (Figure 6.22). The central government in Madrid has made clear that independence for Catalan is not an option. As this edition of the textbook goes to press, the question of Catalan secession remains an open one.

On a more general level, one result of unrest and separatist desires is that the international political map reflects a strong linguistic-religious character. Nevertheless, the distribution of cultural groups is so confoundingly complicated and peoples are so thoroughly mixed in many regions that ethnographic political boundaries can rarely be drawn to everybody’s satisfaction.