GLOBALIZATION

7.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Critically analyze how globalization has affected the practice of religion.

Religion is seen by many people as providing a stable anchor, one that is particularly necessary amidst the flux and turmoil that characterizes globalization. Religious customs, meetings, and obligations serve to form a strong basis of community. Typically, these communities are experienced locally; however, through long-distance pilgrimage, the faithful from across the globe may gather together in one place. Today’s increased mobility and communication make possible religious communities at a truly global scale.

THE RISE OF EVANGELICAL PROTESTANTISM IN LATIN AMERICA

As economic, social, and political changes occur in places, cultural forces such as religion must adapt. For instance, in Chapter 4, we saw how languages change over time in response to immigration, urbanization, and trade-based exchanges. At other times, cultural forces drive changes in politics, economics, and societies. In Chapter 5, we saw how Hispanic immigration to the United States has resulted in major shifts in consumption, political behavior, and social attitudes.

A good example of how the cultural, economic, social, and political arenas work together is provided by the contemporary religious landscape of Latin America and the Caribbean. In this region, Roman Catholicism has dominated the religious landscape since the time of the Iberian conquerors in the late 1400s. More Catholics live in this region than in any other on Earth, with three out of every five Catholics residing here. Brazil is the largest Catholic country in the world in terms of population, with more than 120 million adherents. However, the Catholic Church has been on the decline in Brazil and throughout the region in recent decades. Only about 65 percent of Brazilians are Catholics today, whereas 50 years ago that figure was more than 95 percent. If Protestantism continues to grow as it has in recent years, by 2020 Brazil’s Protestants will outnumber Catholics. What has happened to the region’s Catholics?

Briefly, more and more Latin Americans believe that the Catholic Church has failed to keep in touch with the needs and concerns of contemporary urban societies. Indeed, the naming of Pope Francis of Argentina to the papacy in 2013 may, in part, have been the Church’s attempt to underscore that humility and service to others are important to Catholic leadership. But birth control, divorce, and persistent poverty are issues that simply have not been addressed by Roman Catholicism to the satisfaction of many Latin Americans. The ongoing sexual abuse scandals that have rocked the Catholic Church have also led to diminished loyalty. As a result, more and more are turning to evangelical Protestant faiths, such as the Seventh-Day Adventist and Pentecostal churches (Figure 7.19). The focus of these churches on thrift, sobriety, and resolving problems directly rather than through the mediation of priests is appealing to many. Others find their needs are best addressed by an array of African-based spiritist religions, which include Umbanda, Candomblé, and Santería. Whether Catholicism will ultimately reform from within to become more current, or whether it will continue to lose out to rival denominations, is a key question in regard to the Latin American religious landscape.

292

293

RELIGION ON THE INTERNET

In the mid-fifteenth century, Gutenberg’s printing press made the Bible available to a mass audience. The Internet, proponents argue, represents a similar technological revolution, one that will inevitably attract new adherents to religious faiths. Gathering together regularly in a holy place—a mosque, temple, church, or shrine—is at the heart of most organized religions. Traditionally, people have come together to receive sacraments, sing, pray, and celebrate major life events in houses of worship. With the tens of thousands of religious web sites now in existence, it is no longer necessary to physically go to a place of worship. Rather, you can sit in front of a computer, at any time of the day or night, and read a holy book, submit and read online prayers, engage in theological debate, or watch broadcasts of religious services (Figure 7.20).

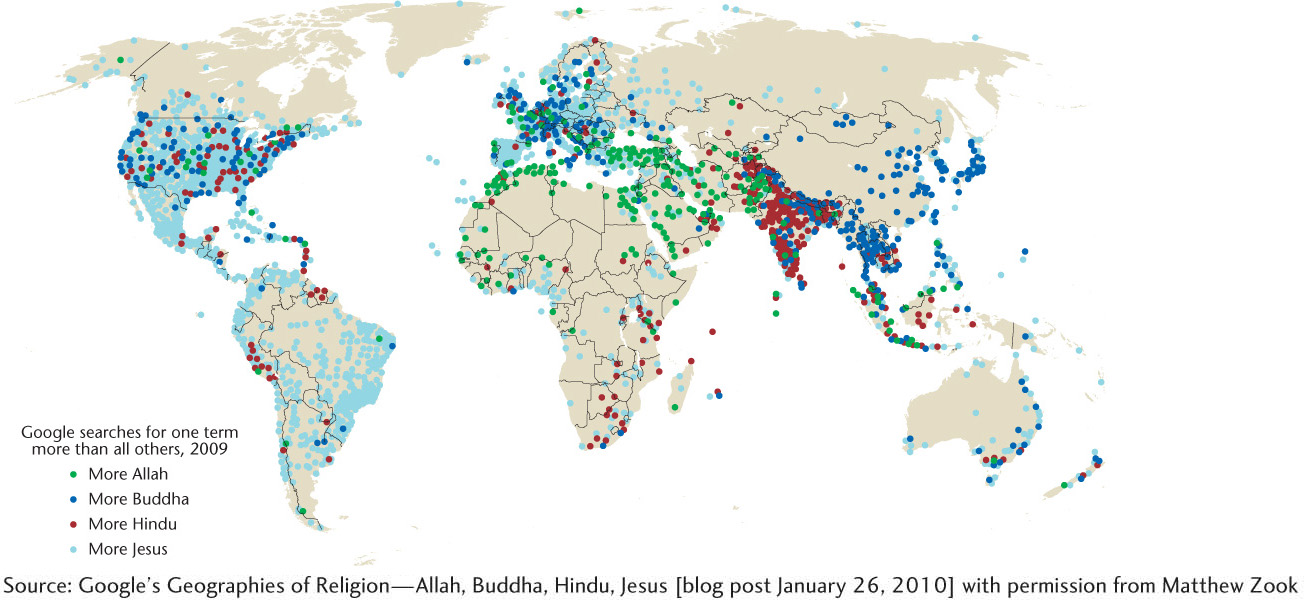

For cultural geographers, the most interesting dimension of online worship concerns what it does to the role of place in a global society. Clearly, the Internet has made it possible to practice religion in a way that is not linked to a specific place of worship, but is this a good thing? Supporters of practicing religion online contend that it allows people to become members of virtual communities that would not otherwise have been available to them in times of spiritual need. Now illness, invalidism, or the pressures of a busy life need not present a barrier to worship. Detractors argue that solitary worship online erodes the place-based communities that are at the heart of many religions. Recall from Chapter 1 that debates center on whether globalization dilutes the role of place and of place-based differences. As people pick and choose elements from the different faiths available online, will religions converge into a watered-down, homogeneous “McFaith”?

RELIGION’S RELEVANCE IN A GLOBAL WORLD

A 2012 Gallup poll revealed that 69 percent of Americans consider themselves very (40 percent) or moderately (29 percent) religious, making the United States one of the more religious nations on Earth. Religiosity will only increase in the United States over time, according to Gallup Editor Frank Newport. Yet the percentage of Americans who do not have a specific religious identification has also increased, and some believe that American culture is becoming more religiously mixed. Newer religious influences, too, are making an entrance onto the American religious stage. For example, if you have ever practiced yoga or meditation, you are engaging in Hindu and Buddhist practices (Figure 7.21). Many Americans do yoga or meditate to enhance physical well-being, to promote spiritual growth, to relieve stress, or even to keep up with the latest trends, rather than as part of a religious practice. Yet they are among the growing number of Americans who have found a blend of Eastern and Western religious practices to be compatible with their beliefs and lifestyles.

294

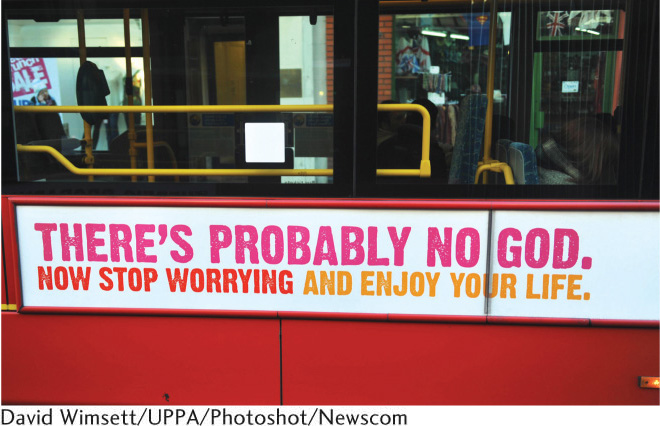

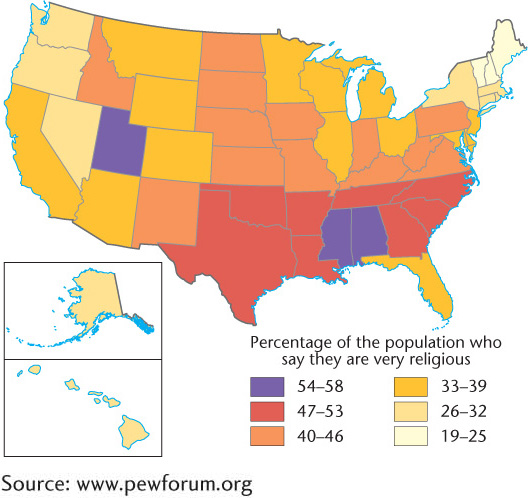

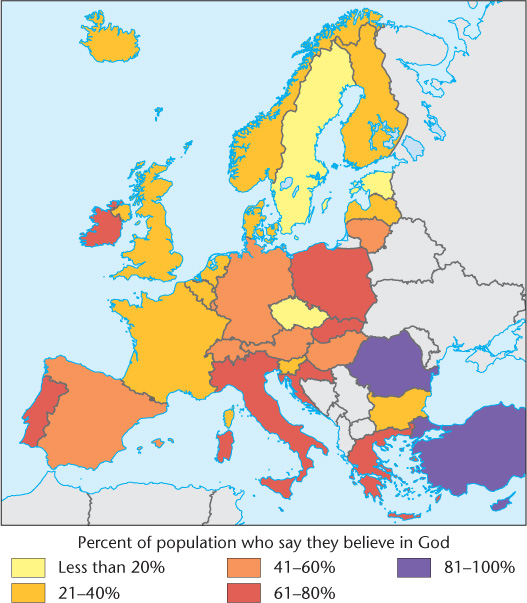

The number of Americans who identify as atheists, agnostics, or adherents to “nothing in particular” stands at about one in five; whereas one in six worldwide, or 1.1 billion people, fall into this category of religious nonaffiliation known as “nones” (Figure 7.22). Across the United States, the importance of religion varies, as depicted in Figure 7.23. In some parts of the world, especially in much of Europe, religious affiliation has declined, giving way to secularization (Figure 7.24). In some instances, the retreat from organized religion has resulted from a government’s active hostility toward a particular faith or toward religion in general. The French government has long—since the French Revolution, in fact—discouraged public displays of religious faith. This extends not only to France’s traditional Roman Catholicism but also to Jews and the rising Muslim population. In 2004 French law banned the wearing of skullcaps, headscarves, or large crosses in public schools, and in 2011 burqas—veils worn by some Muslim women—were outlawed in all public areas.

Yet nonbelief has always been a feature of the religious landscape. In Medieval Europe, according to historian Molly Worthen, “Ordinary people often skipped church and had a feeble grasp of basic Christian dogma. Many priests barely understood the Latin they chanted—and many parishes lacked any priest at all. Bishops complained about towns that used their cathedrals mainly as indoor markets or granaries.” Such patterns once again reveal the inherent spatial variety of humankind and invite analysis by the cultural geographer.

295