Understanding Causal Arguments

Understanding Causal Arguments

Americans seem to be getting fatter, so fat in fact that we hear often about the “obesity crisis” in the United States. But what is behind this rise in weight? Rachel Berl, writing for U.S. News and World Report, points to unhealthy foods and a sedentary lifestyle:

“There is no single, simple answer to explain the obesity patterns” in America, says Walter Willett, who chairs the department of nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health. “Part of this is due to lower incomes and education, which result in purchases of cheap foods that are high in refined starch and sugar. More deeply, this also reflects lower public investment in education, public transportation, and recreational facilities,” he says. The bottom line: cheap, unhealthy foods mixed with a sedentary lifestyle have made obesity the new normal in America. And that makes it even harder to change, Willett says.

— Rachel Pomerance Berl

Many others agree that as processed fast food and other things such as colas have gotten more and more affordable, consumption of them has gone up, along with weight. But others offer different theories for the rise in obesity.

Whatever the reasons for our increased weight, the consequences can be measured by everything from the width of airliner seats to the rise of diabetes in the general population. Many explanations are offered by scientists, social critics, and health gurus, and some are refuted. Figuring out what’s going on is a national concern — and an important exercise in cause-and-effect argument.

Causal arguments — from the causes of poverty in rural communities to the consequences of ocean pollution around the globe — are at the heart of many major policy decisions, both national and international. But arguments about causes and effects also inform many choices that people make every day. Suppose that you need to petition for a grade change because you were unable to turn in a final project on time. You’d probably enumerate the reasons for your failure — the death of your cat, followed by an attack of the hives, followed by a crash of your computer — hoping that an associate dean reading the petition might see these explanations as tragic enough to change your grade. In identifying the causes of the situation, you’re implicitly arguing that the effect (your failure to submit the project on time) should be considered in a new light. Unfortunately, the administrator might accuse you of faulty causality (see “Begging the Question” in Chapter 5, “Fallacies of Argument”) and judge that failure to complete the project is due more to your procrastination than to the reasons you offer.

Causal arguments exist in many forms and frequently appear as part of other arguments (such as evaluations or proposals). It may help focus your work on causal arguments to separate them into three major categories:

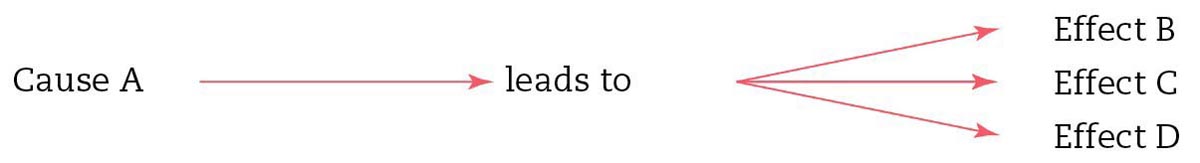

Arguments that state a cause and then examine its effects

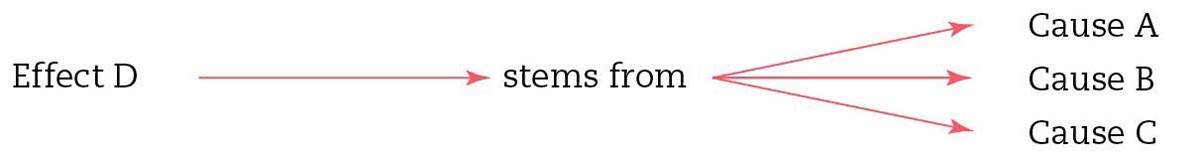

Arguments that state an effect and then trace the effect back to its causes

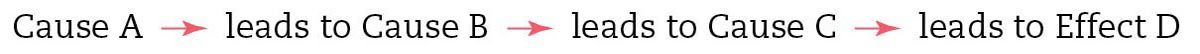

Arguments that move through a series of links: A causes B, which leads to C

and perhaps to D

Arguments That State a Cause and Then Examine Its Effects

What would happen if Congress suddenly came together and passed immigration reform that gave millions of people in the United States a legal pathway to citizenship? Before such legislation could be enacted, the possible effects of this “cause” would have to be examined in detail and argued intensely. Groups on various sides of this hot-button issue are actually doing so now, and the sides present very different scenarios. In this debate, you’d be successful if you could convincingly describe the consequences of such a change. Alternatively, you could challenge the causal explanations made by people you don’t agree with. But speculation about causes and effects is always risky because life is complicated.

In her visual essay “Apples to Oranges,” Claire Ironside depicts the striking effects that would result from the cause she is championing: a move to locally grown, organic food.

Consider the following passage from researcher Gail Tverberg’s blog Our Finite World, from 2011, describing possible consequences of the commitment to increase the production of ethanol from corn:

At the time the decision was made to expand corn ethanol production, we seemed to have an excess of arable land, and corn prices were low. Using some corn for ethanol looked like it would help farmers, and also help increase fuel for our vehicles. There was also a belief that cellulosic ethanol production might be right around the corner, and could substitute, so there would not be as much pressure on food supplies.

Now the situation has changed. Food prices are much higher, and the number of people around the world with inadequate food supply is increasing. The ethanol we are using for our cars is much more in direct competition with the food people around the world are using, and the situation may very well get worse, if there are crop failures.

— Gail Tverberg, Our Finite World

Note that the researcher here begins by pointing out the cause-effect relationship that the government was hoping for and then points to the potential effects of that policy when circumstances change. As it turns out, using corn for fuel did have many unintended consequences, for example, inflating the price not only of corn but of wheat and soybeans as well, leading to food shortages and even food riots around the globe.

Arguments That State an Effect and Then Trace the Effect Back to Its Causes

This type of argument might begin with a specific effect (a catastrophic drop in sales of music CDs) and then trace it to its most likely causes (the introduction of MP3 technology, new modes of music distribution, a preference for single song purchases). Or you might examine the reasons that music executives offer for their industry’s dip and decide whether their causal analyses pass muster.

Like other kinds of causal arguments, those tracing effects to a cause can have far-reaching significance. In 1962, for example, the scientist Rachel Carson seized the attention of millions with a famous causal argument about the effects that the overuse of chemical pesticides might have on the environment. Here’s an excerpt from the beginning of her book-length study of this subject. Note how she begins with the effects before saying she’ll go on to explore the causes:

[A] strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change. Some evil spell had settled on the community: mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was a shadow of death. The farmers spoke of much illness among their families. . . . There had been several sudden and unexplained deaths, not only among adults but even among children, who would be stricken suddenly while at play and die within a few hours. The roadsides, once so attractive, were now lined with browned and withered vegetation as though swept by fire. These, too, were silent, deserted by all living things. Even the streams were now lifeless. Anglers no longer visited them, for all the fish had died.

In the gutters under the eaves and between the shingles of the roofs, a white granular powder still showed a few patches; some weeks before it had fallen like snow upon the roofs and lawns, the fields and streams. No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves. . . . What has silenced the voices of spring in countless towns in America? This book is an attempt to explain.

— Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Today, one could easily write a causal argument of the first type about Silent Spring and the environmental movement that it spawned.

Arguments That Move through a Series of Links: A Causes B, Which Leads to C and Perhaps to D

In an environmental science class, for example, you might decide to argue that, despite reductions in acid rain, tightened national regulations regarding smokestack emissions from utility plants are still needed for the following reasons:

Emissions from utility plants in the Midwest still cause significant levels of acid rain in the eastern United States.

Acid rain threatens trees and other vegetation in eastern forests.

Powerful lobbyists have prevented midwestern states from passing strict laws to control emissions from these plants.

As a result, acid rain will destroy most eastern forests by 2030.

In this case, the first link is that emissions cause acid rain; the second, that acid rain causes destruction in eastern forests; and the third, that states have not acted to break the cause-and-effect relationship that is established by the first two points. These links set the scene for the fourth link, which ties the previous points together to argue from effect: unless X, then Y.

RESPOND •

The causes of some of the following events and phenomena are well known and frequently discussed. But do you understand these causes well enough to spell them out to someone else? Working in a group, see how well (and in how much detail) you can explain each of the following events or phenomena. Which explanations are relatively clear, and which seem more open to debate?

earthquakes/tsunamis

popularity of Lady Gaga or Taylor Swift or the band Wolf Alice

Cold War

Edward Snowden’s leak of CIA documents

Ebola crisis in western Africa

popularity of the Transformers films

swelling caused by a bee sting

sharp rise in cases of autism or asthma

climate change