Seeing Your Project through a Director’s Eyes

The director’s first step is to choose a solid script and build a team of good people to delegate responsibilities to. For your class film project, you may not be able to assign all the necessary jobs out—

DECISION MAKING IN THE MIDDLE OF PRODUCTION

DECISION MAKING IN THE MIDDLE OF PRODUCTION

What if you can’t have everything? Directors face this problem in almost every movie, when time or money is short. To practice how you’d respond, watch a feature or short film with your classmates, and then try to come to a decision on what scene you would cut if you had to choose one. Give clear reasons to justify your decision. Would any other scenes need to be changed if you cut the scene?

Getting the Script and Working It

Even if you wrote the script yourself, try this thought experiment: Walk out of the room, shut the door, open the door, come back into the room, and see the script waiting there for you. Sit down and begin to read it. Imagine that you have just been offered this script to direct. Will you accept the offer—yes or no?

Choosing your material is the single most important decision you will make as a director, even more important than casting your actors. Make sure that the script works, that the emperor is always wearing clothes. The material you choose defines you as an artist; it says what you are interested in, how you see the world, and what you deem worthy of your and the audience’s time. By saying, “I will direct this script,” you are stating that this project reflects some part of your identity and personal vision that you want to share intimately with as many people as possible. Every movie you make, even a two-minute film for class, makes a statement about who you are. Even a two-minute movie takes time, passion, and attention to detail, and, most important, represents a choice: you are making this movie, not that movie.

In contrast to the days or weeks you may spend on a class project, you might spend two years of your life, or more, working on a single studio feature. Such an enormous time commitment is only worthwhile if it reflects who you are. Moreover, the wrong decision or chain of decisions can be costly. Unfortunately, the professional movie business has many examples of directors so hungry to make their mark that they accept scripts just because it will give them the opportunity to direct—not because the scripts are great or because the stories reflect their values. In most cases, those movies don’t succeed creatively or at the box office, and those directors don’t get many chances to work again.

KEEP INFORMATION HANDY

KEEP INFORMATION HANDY

Many professional directors and producers still keep their scripts in a three-ring binder, with different sections for notes, reference images, and contact sheets for everyone involved in the movie.

No matter what kind of movie you are making—class project or webcast, TV show or expensive Hollywood extravaganza—the script will be your formative blueprint. Therefore, as director, you must take responsibility for getting the script right before you start shooting—before you “go to the floor,” in the terminology of the industry. “If it doesn’t work on the page, it won’t work on the stage” is an adage that proves itself true over and over again. Some of the best movies ever made are from scripts that have been worked on for many years by many hands to figure out the right tone—or even what the story is truly about.

In a class situation in which you have written the script yourself, getting it right is more difficult because none of us can really be objective about our own work. It will be helpful to have trusted friends read your script and give their reactions—whether they laughed, felt emotional, liked the characters, or felt involved (or bored) with the story. If you have written a script yourself, you will probably see more in it than is physically on the page. If you are working with a script written by someone else, you are at a creative advantage because you can feel your way through the pages more objectively—more as your eventual audience will.

CONSIDER COLLABORATIONS

CONSIDER COLLABORATIONS

Sometimes it’s advantageous to direct another person’s script—you can be more objective about the writing.

In either case, read the script as if you are not the writer. You should read it first as the director, imagining how you see the movie, how you feel, and what you will tell the actors to evoke in their performances. Then you should read it as if you are one of the actors: does the script give you the dialogue you need and the context (the situations and character background) to deeply develop the characters into who they really are?

As you read the script, take notes and share them with the writer, or with your writer-self if you are the author (see Action Steps: How to Mark Up Your Script, below). Strive to make the script better in every way. Make sure that it is the right length and that you have only the scenes you need, as it is far cheaper and simpler to cut pages than it is to shoot scenes and not use them. At the same time, check that the script devotes enough pages to the most important scenes—that is, the pivotal scenes of plot and emotion. If the drama isn’t on the page, it won’t be on the screen. In ideal circumstances, directors and writers have close collaborations, although far too infrequently do these collaborations extend all the way through production; many movies would be better if the writer were on-set all the time, able to adjust scenes to the necessities of each day’s work.

UNDERSTAND YOUR CHARACTERS

UNDERSTAND YOUR CHARACTERS

Try acting out the different characters’ roles yourself. This exercise (even if you do it in the privacy of your room) will deepen your understanding of the characters’ desires and where the script may not support them.

Once the script is right, you will need to explain, or “sell,” your vision to your collaborators—the people who will help you realize your movie. In your class project, these people will certainly include your actors. Depending on how many things you are doing yourself and how many team members you have, they may also include your producer, cinematographer, editor, and designer.

You will also need to sell your vision to the people who are funding the budget, particularly if you are making a longer or feature-length movie. These individuals may be independent financiers, a movie studio, a production company, or a board of teachers at your school who need to approve the use of school resources for your project. You will likely have one or more meetings to discuss your project, and you will need to be at your convincing best. Often the director’s enthusiasm, energy, and ability to be articulate and answer tough questions make the difference between approval and skepticism on the part of decision makers. This situation occurs most frequently when high-ticket items are on the table, such as casting choices, expensive visual effects, or extra days of shooting. And yes, as the director, you will wind up making some compromises to make everyone happy and get the film approved for production. Pick your battles, and play to win the ones that are most important.

ACTION STEPS

How to Mark Up Your Script

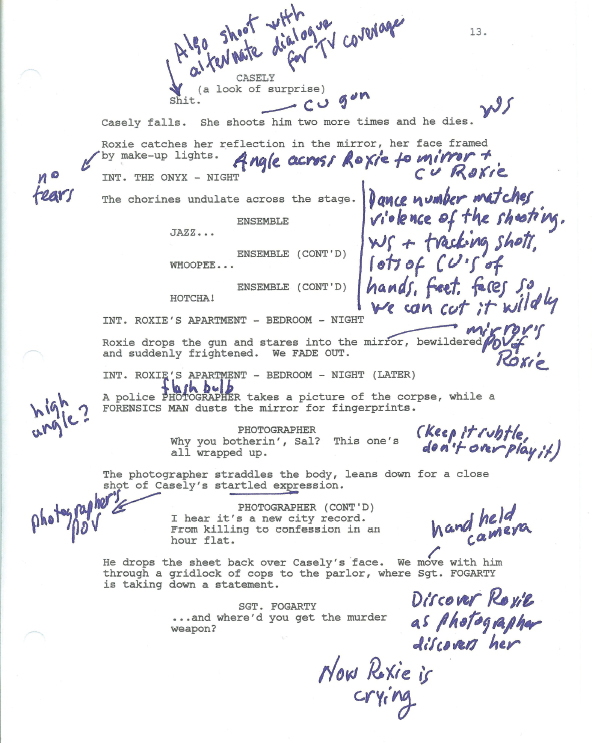

Marking up the script helps the director figure out how to best visualize the story on-screen. To do this, you will need to read the script several times. Each time through, you will be reading for something else. Once you have completed this process, you will have the basis for planning your shoot, and the script will probably look less like a written piece of literature and more like a comic book or even a musical score.

Read the script all the way through for story, character, and emotion. Mark or highlight the places, using different colors for each pass, where you turn the pages fast or when your interest lags. Note when you laugh and when you feel emotional. You will want to make sure the audience feels the same emotions—suspense, fear, joy, humor, tenderness, and so on. This is where you begin to understand and determine the tempo of the story.

Read the script all the way through for story, character, and emotion. Mark or highlight the places, using different colors for each pass, where you turn the pages fast or when your interest lags. Note when you laugh and when you feel emotional. You will want to make sure the audience feels the same emotions—suspense, fear, joy, humor, tenderness, and so on. This is where you begin to understand and determine the tempo of the story. Reread and mark the most important scenes in each part of the script. These will be the scenes you spend the most time shooting, the scenes in which you want to make sure the actors’ performances really deliver and you get enough coverage. Pay attention to the scenes that you did not consider important, and ask yourself why they are there.

Reread and mark the most important scenes in each part of the script. These will be the scenes you spend the most time shooting, the scenes in which you want to make sure the actors’ performances really deliver and you get enough coverage. Pay attention to the scenes that you did not consider important, and ask yourself why they are there. Reread and highlight each main character’s speaking part. Make notes on the type of interpretation you want from each actor, or even note that you want to film a few different interpretations to provide some options in editing.

Reread and highlight each main character’s speaking part. Make notes on the type of interpretation you want from each actor, or even note that you want to film a few different interpretations to provide some options in editing. Reread and highlight each location and the mood, tone, and time of day of each scene. How should you or your production designer visually conceive each location? How can you use the environment to reflect the characters’ emotions and the story’s action?

Reread and highlight each location and the mood, tone, and time of day of each scene. How should you or your production designer visually conceive each location? How can you use the environment to reflect the characters’ emotions and the story’s action? Reread and highlight actors who don’t speak—background actors and extras. Why are they there? How many are needed? What are they doing? Do they contribute to the story of the scene?

Reread and highlight actors who don’t speak—background actors and extras. Why are they there? How many are needed? What are they doing? Do they contribute to the story of the scene? Reread and highlight visual effects or special elements in each scene. It may even be helpful to draw rough thumbnail sketches. By visualizing or previsualizing (as we will explain in Chapter 13) how the final shot should look, you will be better technically prepared for how to shoot it correctly the first time.

Reread and highlight visual effects or special elements in each scene. It may even be helpful to draw rough thumbnail sketches. By visualizing or previsualizing (as we will explain in Chapter 13) how the final shot should look, you will be better technically prepared for how to shoot it correctly the first time. If you are going to direct a particularly complex film or a period movie, you might also highlight costumes/wardrobe, music, sound effects, hair and makeup, vehicles, animals, and other unique aspects of the story. This will help you communicate with the people who will be assisting you in those areas. Again, your notes should not just be a shopping list; they should reveal why each element is needed to tell the story.

If you are going to direct a particularly complex film or a period movie, you might also highlight costumes/wardrobe, music, sound effects, hair and makeup, vehicles, animals, and other unique aspects of the story. This will help you communicate with the people who will be assisting you in those areas. Again, your notes should not just be a shopping list; they should reveal why each element is needed to tell the story. You may want to sketch simple storyboards (see Chapter 4.) or pictures to describe a specific camera setup or framing choice.

You may want to sketch simple storyboards (see Chapter 4.) or pictures to describe a specific camera setup or framing choice.

An example of how a script from Chicago (2002) might have been marked up (top) and a scene from the final film described in the script (bottom)

Now you will be ready to discuss the movie with your collaborators: the actors, cinematographer, producer, and others who will help you realize your vision. You will understand the emotional movement of the story, and also the little pieces—the gears of the clock—that make it function. In rereading the script many times, you will have defined your own vision, and you will be in a position to direct your cast and crew toward that vision. You will be prepared for the looming discussions about budget and schedule. You will be able to make clearer decisions about whom you want to cast, how you want to shoot the scenes, and what the sets should look like. Although your creative collaborators are very important, it is your job to guide them (while being open to their ideas); you do not want to be a “picker”—someone who relies on the crew to offer different creative choices and then picks one. You will also begin to sense the appropriate editorial style for this particular story and better understand what type of material you need to bring back to the editing room.

Casting Actors

Good performances are the lifeblood of a film. Practically any other aspect of a film can be less than optimal, but if the actors play their parts well, the film as a whole can succeed—

A professional production might be cast-

If you know the actor’s work, you may simply offer the role, which means that if he or she says yes, the actor has the part with no audition necessary. But if you have not worked with an actor before, or seen a great deal of that actor’s work on-

You should always video your auditions, because the way an actor appears in the room may not convey itself the same way on-

It’s customary to have another actor read the scene with the actor you are auditioning. For each role you are casting, use the same reading actor in the opposite role so that you have a clear picture of the auditioning actor’s performance. Once you have held your first round of auditions, you will typically call back your top choices for final rounds. In these callback auditions, you will probably ask the actors to perform longer scenes, and you will try different combinations of actors to find just the right chemistry for your story, because the chemistry between acting partners greatly influences the outcome of each scene.

How do you communicate with actors? Specifically and respectfully. If you have never taken an acting class, you should. Even a few acting lessons will give you a window on the process an actor must go through, because an actor’s job may be one of the most difficult on a film production. Actors must stay in a state of intense concentration, summon up their characters at a moment’s notice and in the short bursts of camera takes, repeat exactly the same action over and over again for multiple takes, and say the screenwriter’s dialogue as if it were their own, often in an order that’s nonsequential from the script. Actors must create complete characters with whole lives, using only the tools of their imagination and the character’s few scenes in the script.

Never forget that the actors may be relying on real, often deeply personal, emotional experiences from their lives to help them build their performance. As the director, you must get what the story needs while being sensitive to the actors, who may literally be baring their souls to the world. Even if a movie is about only one character, the movie does not show every moment of that character’s life—

ACTION STEPS

The Audition Process

The following steps are appropriate for a class project or a low-

Break down the characters in the script. Identify them by name, and write a one-

Break down the characters in the script. Identify them by name, and write a one-sentence description of the role.  Announce that you are holding auditions. Post a notice, and provide a way for interested actors to schedule their audition time. Possible places to post your audition notice include online casting services, local theaters, and drama schools. Use trained or professional actors, if possible.

Announce that you are holding auditions. Post a notice, and provide a way for interested actors to schedule their audition time. Possible places to post your audition notice include online casting services, local theaters, and drama schools. Use trained or professional actors, if possible. For first auditions, allow 15 to 20 minutes per actor. For callbacks, allow 30 to 60 minutes, depending on the role. Stick to your schedule, and respect the actors’ time. See everyone you have asked to audition, even if you are positive the first audition gave you the actor you need. Not only is it the professional thing to do, but you never know what the actor in the waiting room will offer.

For first auditions, allow 15 to 20 minutes per actor. For callbacks, allow 30 to 60 minutes, depending on the role. Stick to your schedule, and respect the actors’ time. See everyone you have asked to audition, even if you are positive the first audition gave you the actor you need. Not only is it the professional thing to do, but you never know what the actor in the waiting room will offer. Video the auditions. If you see a lot of people, this will help you remember them and also see how they appear on-

Video the auditions. If you see a lot of people, this will help you remember them and also see how they appear on-screen. Always have the actors state their names on the video.  Give actors at least one day’s notice, so that they have time to prepare. When the actor comes in, introduce yourself and take a moment to explain the movie and the character’s role in it. This is called setting up the scene. Then ask the actor to perform the scene.

Give actors at least one day’s notice, so that they have time to prepare. When the actor comes in, introduce yourself and take a moment to explain the movie and the character’s role in it. This is called setting up the scene. Then ask the actor to perform the scene. Now ask the actor to make a performance change. This is called making an adjustment. You might ask the actor to consider what happened to the character immediately before the scene starts, to pick up the pace, or to try the scene with a different intention. Asking the actor to make an adjustment accomplishes two things: it lets you see how much variation or texture the actor brings to the role, and it gives you a sense of how you might work with the actor by seeing how well he or she follows your direction.

Now ask the actor to make a performance change. This is called making an adjustment. You might ask the actor to consider what happened to the character immediately before the scene starts, to pick up the pace, or to try the scene with a different intention. Asking the actor to make an adjustment accomplishes two things: it lets you see how much variation or texture the actor brings to the role, and it gives you a sense of how you might work with the actor by seeing how well he or she follows your direction. After you have made your decisions, first call the actors you want to cast. Confirm that they are available and have accepted their parts before you call the other actors who auditioned. For most student films, whether or not an actor is available for shoot dates is actually the very first question asked.

After you have made your decisions, first call the actors you want to cast. Confirm that they are available and have accepted their parts before you call the other actors who auditioned. For most student films, whether or not an actor is available for shoot dates is actually the very first question asked. Call the actors who did not get cast. Although actors never want to hear they didn’t get the parts they auditioned for, it is far worse—

Call the actors who did not get cast. Although actors never want to hear they didn’t get the parts they auditioned for, it is far worse—not to mention unprofessional— if you never call them at all. Hearing the words “I’m sorry, I decided to cast the role differently” is something actors must unfortunately get used to. You, as the director, or your producer or casting director, should make a personal call to each actor you didn’t cast. Best to do it with grace and kindness— you may want that actor for your next project.

Selecting Department Heads

Just as you take care in choosing the right actor for each role, so, too, must you select your behind-the-camera colleagues with care. The director’s most important collaborators are the director of photography, the production designer, the editor, and, on films with significant visual effects, the visual effects designer or supervisor. When we include the producer in the mix (who, as stated earlier, is the one who usually chooses the director), this cohesive group forms a production’s “inner circle.” These people (or functions, because you may be doing some of these jobs yourself for your class project) form the basis of the creative decision-making relationships.

LISTEN TO OTHERS AND YOURSELF

LISTEN TO OTHERS AND YOURSELF

When meeting with your crew, present a clear, direct vision, which will give them the secure feeling that you are a leader. Listen to their suggestions and solutions, yet feel comfortable rejecting what doesn’t match your intention.

Agents, Managers, and Lawyers

If you pursue filmmaking at a professional level, you will do business with agents, managers, and lawyers. (You might even become one yourself.) Your first encounter with an agent or a manager may be when you are casting an actor who has acted professionally. Agents, managers, and lawyers are collectively referred to as representatives. Agents and managers represent actors, directors, producers, composers, and people from many other fields, who are called clients; most agents and managers specialize in one or two types of clients, such as actors or cinematographers. Agents offer career guidance, seek employment for their clients, and negotiate employment or business deals on their clients’ behalf. Their work and business practices are regulated at the state level, and in most states, they must have a license to practice their work.

Managers generally have far fewer clients than do agents and offer more personalized guidance and career strategies. In most states, managers don’t negotiate deals—they coordinate with agents or attorneys on business matters. Lawyers draft contracts and negotiate the finer, or more technical, points of most deals, often looking to the long-term implications of some contract provisions; only lawyers have the legal training to offer competent legal opinions, and everyone is well advised to consult a lawyer before signing any contract.

Agents and managers make their money by charging a percentage of their clients’ earnings. This fee is called a commission. An agent’s commission is typically 10 percent, whereas a manager’s commission is typically between 10 and 15 percent. Lawyers generally work on an hourly basis, although in some areas of entertainment negotiations, they, too, will work on a percentage basis, in which case they will typically charge 5 percent.

MARKING UP A SCRIPT

MARKING UP A SCRIPT

Using the techniques described on this page, think like a director and practice marking up two pages of a script. You may either use a script of your own or find screenplays that have been produced as movies at www.dailyscript.com.

In considering your possible department heads, focus on personal qualities as well as technical skills. A less-skilled technician often wins a job over a superior craftsperson purely on the basis of being easier to work with. As the director, you need to get a feel for the working relationship you might have with each candidate. Everyone is an artist in his or her own right, and you should treat each of your candidates that way. At the same time, their job is to make a great movie and not let their personal issues or egos get in the way. Choose people with whom you can have open and honest communication, who will not be afraid to tell you you’re wrong, yet will still do what you need even if they disagree. Also, consider whether each person will interact well with the others. For example, the cinematographer needs to have a comfortable and trusting relationship with the actors.

The skills represented by typical department heads are covered in subsequent chapters; here, we’ll look at some of the ways you should go about selecting your creative teammates and the most important criteria to take into account. Of course, each movie is unique and may require additional steps or considerations.

Make sure they have been given an opportunity to read and study the script.

Make sure they have been given an opportunity to read and study the script. Ask to see samples of prior work. You’re not looking for dazzle and flash—you’re looking for inventiveness and fidelity to the story. A designer or an editor who calls more attention to the design or the editing than to the story or the characters won’t serve you well.

Ask to see samples of prior work. You’re not looking for dazzle and flash—you’re looking for inventiveness and fidelity to the story. A designer or an editor who calls more attention to the design or the editing than to the story or the characters won’t serve you well. Determine if their creative vision for the film is aligned with yours.

Determine if their creative vision for the film is aligned with yours. Make sure they can work within your schedule and budget. Anybody can make something look great with a lot of time and money, but you need teammates who can achieve superior results fast and with little or no money. Look for people who come up with creative solutions to the problems they face, who can think on their feet, and who can adapt to changes quickly.

Make sure they can work within your schedule and budget. Anybody can make something look great with a lot of time and money, but you need teammates who can achieve superior results fast and with little or no money. Look for people who come up with creative solutions to the problems they face, who can think on their feet, and who can adapt to changes quickly.