Management Overview

You may be the only person in charge of making and managing the Plan for your student film, or you may have help from friends, fellow students, family members, or even complete strangers eager to get experience. No matter what, production management tasks are plentiful at all levels of filmmaking, and strategies for dealing with them must be put into place. These tasks include creating and updating the aforementioned schedule and budget; managing the day-to-day logistical matters related to acquiring and moving cast, crew, and equipment from one location to the next; feeding people and getting expenses paid; solving problems as they arise; managing money; and answering to your professors or investors, if there are any.

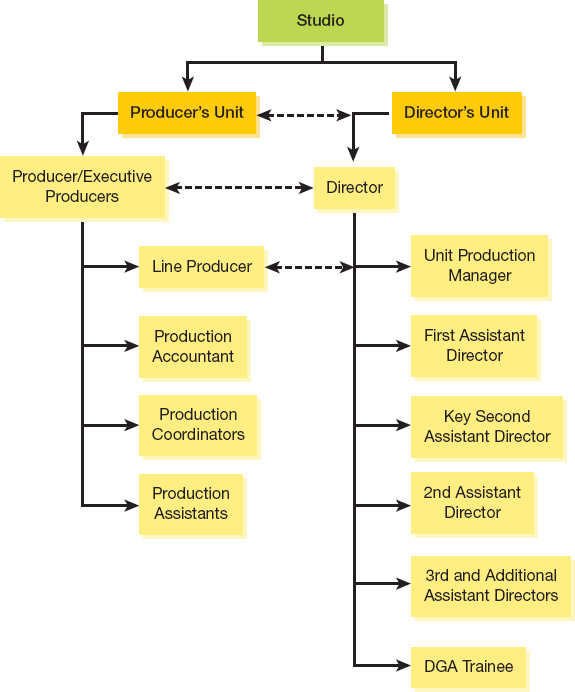

In the professional world, these activities are handled by a seasoned production management team, which can include any number of producers who handle various executive, financial, management, or logistical tasks, in collaboration with more hands-on department heads on a day-to-day basis. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the lead producer is the ultimate manager and decision maker on a movie project, and on student projects, that person is you, no matter how you divide up the work or whom you bring in to collaborate with you. But from a basic, nuts-and-bolts, daily-grind point of view, the most crucial management authority on the production will be the unit production manager, or UPM, sometimes called the line producer or co-producer, although these exact titles have more rigid and official (and not always identical) meanings on professional productions and across different mediums, such as film as compared to television. This is because of how they are classified as union jobs by the Directors Guild of America. On union shows, the line producer will likely be more involved in creative matters, such as casting, actor contracts, and script changes, whereas the UPM will stay focused largely on physical production issues: crew hiring, transportation, permits, scouting, business matters, schedules, budgets, department heads, and so forth. For the student work you are doing right now, these job distinctions are not a significant concern, as they will likely be melded into a single position or split up based simply on what is feasible with few resources, but you should be aware such distinctions exist as you advance in your film career.

SOFTWARE CAN HELP

SOFTWARE CAN HELP

One of the most commonly used management tools for most filmmakers at any level is Movie Magic Budgeting and Scheduling software, but there are many others, such as Microsoft Project, FastTrack Schedule 10, QuickBooks, not to mention common Excel spreadsheets.

An organizational flow chart of a production management team

YOU CAN’T DO IT ALL

YOU CAN’T DO IT ALL

Aggressively seek help and delegate jobs—don’t try to manage all details yourself. Much of producing a movie with few resources involves gathering your production management team in whatever form it takes each day and regularly distributing lists of action items to everyone, from crucial issues to the mundane.

In terms of basic duties, the UPM is the chief strategist/problem solver when it comes to day-to-day production management work. The person handling those duties will carry ultimate responsibility for making sure the project is completed on time and on budget. You will likely be handling this job as well on most of your early student films, but you might eventually bring in others to assist you on some or all of the UPM’s responsibilities—either formally or informally. But no matter how you split up the work, among the UPM’s responsibilities will be the following:

Organizing actor and crew contracts, if any

Organizing actor and crew contracts, if any Negotiating union contracts, if any

Negotiating union contracts, if any Arranging location scouts and permits, if any

Arranging location scouts and permits, if any Securing releases and interacting with local authorities for permissions and on safety issues

Securing releases and interacting with local authorities for permissions and on safety issues Scheduling and budgets

Scheduling and budgets Interacting with department heads

Interacting with department heads Organizing crew meals and transportation

Organizing crew meals and transportation Solving logistical problems

Solving logistical problems

The UPM must balance the intersection between money and the creative vision during production. Thus, a UPM not only needs to be proactive and anticipate problems before they arise, and then be ready with a contingency plan when they do, but also needs to know when and where to compromise. The job requires excellent communication skills, a gift for multitasking, and the conciliatory approach of a diplomat embarking on an international peace treaty when faced with issues that can arise between the creative team and the crew (see Business Smarts: Business, Insurance, and Legal Requirements, below).

Typically, the UPM is too busy handling business matters, filling out paperwork, pondering upcoming logistical challenges, or dealing with problems or crises off-site to manage moment-by-moment affairs during production. On professional films, that job therefore falls to the assistant directors, with the first assistant director (first AD) serving as “the general on set,” according to Tim Moore, and often two second assistant directors directly below the first AD. As discussed in Chapter 3: Directing, the assistant directors track each day’s shooting schedule against the production schedule; prepare daily call sheets; and ensure that the set is running smoothly, moving the director and crew into all the setups planned for the day, with actors and crew positioned according to your plan and needs.

BUILDING A TEAM

BUILDING A TEAM

Presuming you have absolutely no funds to pay anyone for anything, take a student project you are developing or investigating, or one you would like to work on in the near future, and write a two-page description of how you would propose putting together a production management team for that project, and how you would delegate responsibilities. The proposal does not necessarily have to reflect what ends up being your final plan, though it could end up being a nice template, but it should be a realistic and logical description of the people you believe you could actually access and bring into the project to play specific managerial roles.

Again, you likely won’t be hiring a team of people this extensive and structured for your student project, but even with limited resources, it’s always a good idea to get help when you can, particularly where the business and management side of the project is concerned. Filmmaking is, after all, a collaborative art. You have to be honest about your strengths and weaknesses. If you do not have much business experience or are not an organized person, challenge yourself to find help filling in those gaps. As Jon Gunn advises, “If you know someone who is well organized, detail oriented, good at negotiating, or who has experience planning events, they could be very helpful on an independent film. A parent or family friend or neighbor might be able to arrange food or parking or negotiate for a location. There are a lot of tasks to be handled, and there are undoubtedly people you know who would be willing to help you, so don’t be afraid to ask.”

Business, Insurance, and Legal Requirements

Among the least enjoyable but most important aspects of filmmaking are certain business, insurance, and legal requirements, which may or may not apply to you as student filmmakers but which you need to know about in order to figure out if they will impact your work. Failing to do your due diligence in these areas, and to adequately fill out paperwork and keep proper records, could end up costing you money, involve you in legal entanglements, and delay or even ruin your project. Therefore, investigate and learn more about the following issues:

Releases. These permit you to film and show certain individuals, places, and logos in your movie. Corporate logos, such as the famous Apple logo, are intellectual property. Someone owns them, and they only appear in movies when someone pays for the right or otherwise secures permission. If your movie is not a profit-making venture, it might not matter, but you need to be sure. What if your film later ends up on YouTube?

Releases. These permit you to film and show certain individuals, places, and logos in your movie. Corporate logos, such as the famous Apple logo, are intellectual property. Someone owns them, and they only appear in movies when someone pays for the right or otherwise secures permission. If your movie is not a profit-making venture, it might not matter, but you need to be sure. What if your film later ends up on YouTube? SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists), other union considerations, and Workers’ Comp. Union agreements are needed to allow you to use union personnel on your project. Most likely, for a small, not-for-profit student film, you may not want to use union personnel, but you should still know the rules at your school and in your area, and the status of any actors you cast. If you cast an actor with a SAG-AFTRA card, you may end up having to pay that person union rates. Even for non-union individuals who aren’t being paid, the law may require workers’ compensation insurance or other types of coverage for anyone working on-set, depending on the state you’re filming in. Various craft unions and guilds also define many of the crew positions, as well as their respective pay rates, how many need to be hired, conditions of work, the number of hours they can work, required breaks, and so on. You need to understand what union requirements are in the area where you are filming in order to know if they will, or won’t, impact your student production.

SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists), other union considerations, and Workers’ Comp. Union agreements are needed to allow you to use union personnel on your project. Most likely, for a small, not-for-profit student film, you may not want to use union personnel, but you should still know the rules at your school and in your area, and the status of any actors you cast. If you cast an actor with a SAG-AFTRA card, you may end up having to pay that person union rates. Even for non-union individuals who aren’t being paid, the law may require workers’ compensation insurance or other types of coverage for anyone working on-set, depending on the state you’re filming in. Various craft unions and guilds also define many of the crew positions, as well as their respective pay rates, how many need to be hired, conditions of work, the number of hours they can work, required breaks, and so on. You need to understand what union requirements are in the area where you are filming in order to know if they will, or won’t, impact your student production. Permits. As discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 4), you may need location permits from local authorities to film in certain places, but you might also need certain fire and safety permits for particular kinds of stunts or effects work, or to have certain kinds of crew or equipment or numbers of people in certain locations. You may need local authorities to authorize such things, and you may have to pay for a fire or police official to be present during filming of such sequences.

Permits. As discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 4), you may need location permits from local authorities to film in certain places, but you might also need certain fire and safety permits for particular kinds of stunts or effects work, or to have certain kinds of crew or equipment or numbers of people in certain locations. You may need local authorities to authorize such things, and you may have to pay for a fire or police official to be present during filming of such sequences. Damage protection insurance. As the name implies, equipment and vehicle rental companies often require filmmakers to carry this kind of protection to cover damage to equipment rented from them. Location permits are frequently granted only on the condition that you also carry insurance to guarantee that any damage to property is covered. Sometimes companies that specialize in film production offer special entertainment packages that cover all forms of damage throughout principal photography for low-budget films.

Damage protection insurance. As the name implies, equipment and vehicle rental companies often require filmmakers to carry this kind of protection to cover damage to equipment rented from them. Location permits are frequently granted only on the condition that you also carry insurance to guarantee that any damage to property is covered. Sometimes companies that specialize in film production offer special entertainment packages that cover all forms of damage throughout principal photography for low-budget films. Comprehensive general liability insurance. Likewise, special coverage or signed waivers of coverage will often be required before you will be granted permits to stage dangerous or complicated stunts or pyrotechnic effects. This kind of insurance can be quite expensive, and students may not be able to easily purchase it or even acquire it through their film school policies. In any case, your school likely won’t approve you moving ahead with stunts that are too dangerous—nor should they.

Comprehensive general liability insurance. Likewise, special coverage or signed waivers of coverage will often be required before you will be granted permits to stage dangerous or complicated stunts or pyrotechnic effects. This kind of insurance can be quite expensive, and students may not be able to easily purchase it or even acquire it through their film school policies. In any case, your school likely won’t approve you moving ahead with stunts that are too dangerous—nor should they. Copyrights. This involves registering your work with the proper authorities, identifying you and any partners or financiers as the legal owners, so that no one can later copy or steal the work (see Chapter 2). Copyrights require paperwork and fees to be filed. But you also need to check with your school and find out who will own the copyright to your student film—you or the school?

Copyrights. This involves registering your work with the proper authorities, identifying you and any partners or financiers as the legal owners, so that no one can later copy or steal the work (see Chapter 2). Copyrights require paperwork and fees to be filed. But you also need to check with your school and find out who will own the copyright to your student film—you or the school? Contractual responsibilities. You need to read and understand all contracts before signing them, and most, if not all, may require legal advice. For instance, if you have anyone providing financing or offering distribution on the condition that you complete your movie by a particular date, you may be required to pay for a

completion bond—another form of insurance—to guarantee your film will be finished.

Contractual responsibilities. You need to read and understand all contracts before signing them, and most, if not all, may require legal advice. For instance, if you have anyone providing financing or offering distribution on the condition that you complete your movie by a particular date, you may be required to pay for a

completion bond—another form of insurance—to guarantee your film will be finished. Other Insurance. On a film of even modest size, your insurance package may also include: E&O, or errors and omissions coverage, which provides protection in case you unintentionally infringe a known piece of copyrighted material; coverage for the budget of the film in case of the death or inability of an actor during production; and additional protections you may discuss with your insurance broker.

Other Insurance. On a film of even modest size, your insurance package may also include: E&O, or errors and omissions coverage, which provides protection in case you unintentionally infringe a known piece of copyrighted material; coverage for the budget of the film in case of the death or inability of an actor during production; and additional protections you may discuss with your insurance broker.Many schools around the country can and do help with these issues. Some of them, in fact, already have standard deals in place with entities such as SAG-AFTRA, whereby union actors can perform in student films for special rates and under certain conditions. In addition, some also offer certain basic types of liability insurance for projects done through the school. In some schools, you may have already paid for your portion of this insurance as part of your tuition fee package or through some other arrangement. Your school may have an office that offers special guidance on such matters, as well as how to apply to festivals, pursue distribution opportunities, and so on. Therefore, your first stop in sorting through these complicated matters needs to involve asking your professor or film department administration office for guidance.

Network through this class, your professor, your film department, your school, your friends and family, and be aggressive about reading industry trade publications and going to industry events, trade shows, screenings, and panel discussions, where you can meet people, ask questions, and seek advice. It doesn’t matter if these people have any previous experience or involvement in the film world. What matters is their skill set and whether or not you think they can help you manage your project.