Read with Focus

Once you’re prepped and ready to go, take the next step: Complete your reading. Your goal is to absorb, understand, and remember information so you can use what you’ve learned to write papers, answer test questions, and gain insights into topics covered in your other classes. But you won’t be able to remember every word in your reading assignments — no one can. So you need to read with focus: Figure out what information is most important, and concentrate on that. To do this, use your critical thinking skills to identify key information and to evaluate the quality of that information. And use your active learning and metacognition skills to select reading strategies that work best for you, depending on your learning preferences and the subjects you’re studying. The following tactics can help you focus on the most important information.

Mark Up Your Reading Material

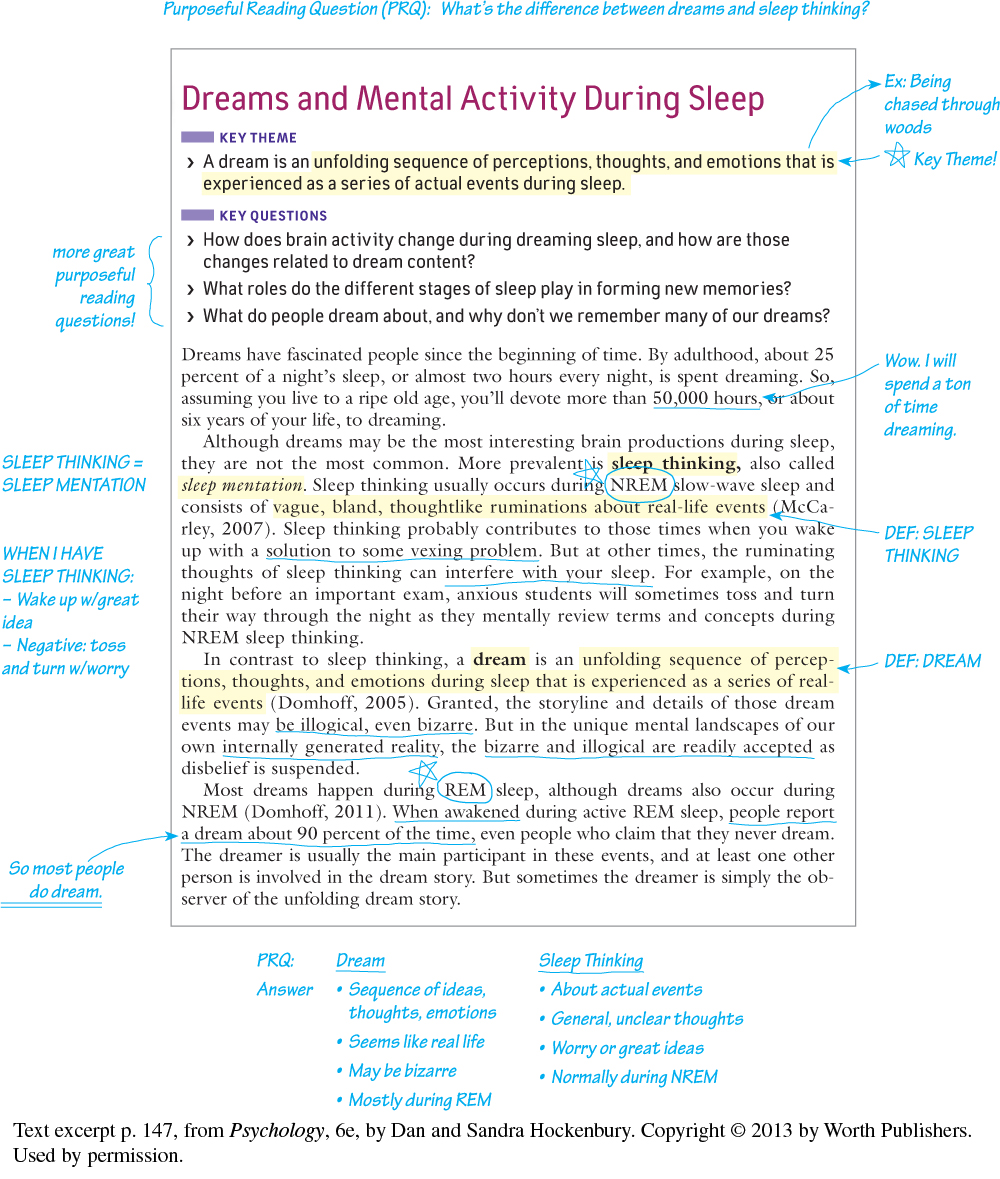

Marking up a text helps you interact with the material you’re learning, which in turn helps you understand and remember it. You can mark up reading material in several ways (see Figure 6.4), including annotating the margins of your text, highlighting and underlining key words and phrases, and taking notes.

Annotate. You can annotate your reading material by jotting down quick notes, inserting your own examples, drawing symbols (“DEF” might indicate a definition; “EX” might call out an example), and writing quick summaries in your own words — all in the margins of the book or article. Making notes and restating information in your own words requires you to process information more carefully than if you just highlight or underline (see the next section). Annotating takes some time, but it’s worth it — you’ll remember the material better later on, and you’ll have notes that you can use to study.

Are you reading online? You can still use this approach, but instead of a pen or pencil, use digital tools to mark up the content (see the Read Online Course Materials section later in this chapter).

Highlight and Underline. Highlighting and underlining help you identify main ideas and call out key content such as math formulas, diagrams, and definitions. These popular techniques offer a quick and easy way to spotlight important points and then locate that information later when you’re studying. But research shows that when using these techniques, you should proceed with caution: If you highlight or underline mindlessly, then you’re not processing the information carefully.3 Later on, you might find it hard to remember what you’ve read. In addition, if you highlight or underline too much content, the page will become so busy that your markups will be useless.

ACTIVITY: Give students a sample passage and ask them to highlight the most important material discussed in that passage — approximately 10 percent of the text. As a class, discuss what students highlighted and their rationale.

To take a more focused approach to using these tools, read each section of the material before you make any marks. Ask yourself: What are this section’s main ideas? Then go back to the material and highlight or underline only the content that’s most important.

Take Notes. You can take notes while you read using a laptop or notebook, and you can return to these notes when it’s time to study. If your goal is to read the material just once, take thorough notes (see the note taking chapter for specific methods). Later, as you prepare for a test, you’ll study directly from these notes. If you plan to reread the material, try taking broad notes as you read. For example, jot down key words with definitions, record where to find diagrams or charts in the chapter, or write a short summary of the material.

As you read and take notes, look for the answers to your purposeful reading questions, and write them down as you find them. For example, if one of your questions is “What are polynomials?” and you come across the definition of polynomials in the chapter, add it to your notes or mark it in your book so that later you can go back and study the definition.

Think Critically about What You Read

College would be simpler if everything you read was trustworthy, but that’s not always the case. In fact, one of the best skills you’ll develop in college is the ability to evaluate the quality, accuracy, and usefulness of information — that is, to think critically about what you’re reading.

As you read, form your own conclusions about what you’re reading, based on your evaluation of the information. For example, let’s say your instructor assigns two readings about wage inequality between men and women. In one of the readings, the author argues that women are paid less because they’re more likely to work part-time, take time off to have children, and enter occupations that pay less than more male-dominated ones. In the other reading, the author suggests that the pay gap stems from discriminatory practices in the workplace, such as male managers setting lower salaries for women or selecting other men for promotions. As a critical thinker and an active reader, you can evaluate the soundness of the arguments presented in each reading and the authors’ credentials and then formulate your own thoughts about what’s causing the gender pay gap.

In addition to evaluation, another important component of critical thinking is application. Applying what you read to your own life or to everyday situations can help you learn and remember the material. Take Michelle, who’s reading about eye contact and culture in her communications textbook. To connect the material to her own life, she thinks about how disconnected she felt on a recent first date when her date wouldn’t look her in the eye, and how welcoming it feels when Andy, the barista at the coffee shop, looks right at her and smiles. Michelle also thinks about how one of her coworkers seldom makes eye contact with colleagues during meetings. He recently moved to the United States, and Michelle wonders if his behavior during meetings stems from the cultural norms he grew up with. By making these connections, Michelle is processing the material more deeply, a strategy that will help her remember what she learned later in the term.

FOR DISCUSSION: Ask students how the information they’re learning in this chapter connects to something they’ve experienced in their own lives or to an everyday situation. Have them provide examples. If it’s difficult to get the conversation started, begin by providing an example of your own.

Clarify Confusing Material

As you read, you’ll inevitably run into content — a word, a concept, an example — that you don’t understand. Try these techniques to clarify confusing content.

Carefully reread the material. You might understand it on the second or third try.

Expand your vocabulary. Look up definitions of unfamiliar words, and use the words in sentences to grasp their meaning.

Move on. Something you read later in the material might clarify things. Or simply giving yourself a few minutes away from the confusing content might help you see something you missed the first time.

Ask a classmate or a knowledgeable friend to explain the material.

Find help online. Reading another author’s interpretation of confusing content might help. However, remember that not all Internet sources are trustworthy, so use your critical thinking skills to evaluate what your search engine throws at you.

Ask your instructor. His or her job is to help you learn, so don’t be afraid to ask for clarification when you have questions.

FOR DISCUSSION: Before class, review several vocabulary and dictionary apps for smartphones and tablets. Which seemed particularly useful? Bring your findings to class, and invite students to share their favorites.

ASK FOR HELP WITH READING CHALLENGES

Many students find reading to be challenging but are uncomfortable asking for help. Is this true for you? If so, try thinking about your situation this way: Just as athletes, musicians, and business executives work with coaches to improve their performance, you can work with people on campus to improve your reading performance. Knowing when and how to ask for help is a valuable skill that will benefit you now and in the future. So take a moment to consider the following helpful resources.

Staff at the Learning Assistance Center. Most campuses have a tutoring or learning support center that focuses on helping students with reading, studying, and many other skills essential for college success. To find the office on your campus, browse your school Web site or type keywords such as “tutoring” or “academic support” into the site’s search function.

Advisers. Advisers are used to working with students who need assistance, and they have likely helped others in your position. Talk with your adviser or someone in the advising office about how to approach reading.

Staff at the Disability Services Office. If you have a diagnosed learning disability or think you might have a reading disability, visit your school’s disability services office to find out how the staff there can help.

CONNECT

TO MY RESOURCES

List two individuals, departments, or offices at your college that could help you improve your ability to read course materials. How might they help you? For example, can they teach you how to read faster or mark up your texts more effectively?

FOR DISCUSSION: Briefly review with the class what campus and community resources are available for students who would like to improve their reading skills.

Boost Your Reading Efficiency

Reading efficiently can help you stay focused on the most important material so that you don’t waste time and effort on less relevant content. You can supercharge your reading efficiency by mastering the art of concentration and by increasing your reading speed.

Sharpening your powers of concentration can help you avoid an all-too-common problem: realizing that your mind has wandered and that you have no idea what you just read. Try the following tactics for enhancing your concentration.

FURTHER READING: Psychology Today offers a free attention span test online. Simply search for Psychology Today’s “Attention Span Test” to learn more about your own attention style.

Set brief reading goals. Create very short-term, focused reading goals if you’re unfocused. Instead of trying to read for ninety minutes, for example, set a goal of reading four pages from your religious studies book and reading your marketing text for fifteen minutes. Dividing your reading into small chunks and switching between topics can help you cover all of your reading assignments without feeling overwhelmed and losing focus.

Move around. If you’re bored with your reading and can’t concentrate, get up and move. Take a one-minute walk around the stacks in the library, grab thirty seconds of fresh air outside, or throw your book into your bag and head for a different study carrel. Then get back to reading.

Remove distractions. If distractions — noises, people passing by, text message or e-mail pings — are preventing you from concentrating, remove them. For instance, turn off your phone, or close the curtains or blinds so you can’t see what’s happening outside. See the chapter on organization and time management for more ideas on creating a distraction-free zone.

FURTHER READING: To learn more about how exercise improves brain function and concentration, visit http://www.sparkinglife.org.

In addition to sharpening your powers of concentration, increasing the speed at which you read can help you make better, more focused use of your reading time. Reading faster is a skill that you can build with practice. Before you spend any of your money on a speed-reading class, try the following techniques.

ACTIVITY: Use this activity to prompt discussion about how distractions affect reading habits. Give students five minutes to read a short article. As they read, create distractions — turn on music, talk loudly about your favorite movie, toss a ball and ask students to catch it, etc. Then give the class a short quiz on the reading. Were students able to retain what they read?

Read in chunks. Instead of reading one word at a time, try reading groups of words. (Here’s how you could “chunk” the preceding sentence: “Instead of reading — one word at a time — try reading — groups of words.”) As you focus on groups of words, your speed will increase. There’s no one “right” way to do this; when you read, try different groupings to see what works for you.

Use a cue. Place your fingertip at the middle of the first line of a paragraph. Slowly drag this “cue” down the middle of the paragraph, reading each line as you go. When you use a cue, your eyes follow your finger instead of moving left to right across each line. This forces your mind to read each line in chunks rather than each word individually. This technique may take some practice, but the more you do it, the easier it gets.

Skim. If you have a lot of reading to do and not much time, skim the material. Move your glance quickly across each line or read the first and last sentence of each paragraph. Skimming isn’t the most effective strategy for deep understanding of material — you’ll likely trade some comprehension for speed — but it’s better than not reading at all. Just try not to use this approach unless you’re pressed for time.

voices of experience: student

GAINING CONFIDENCE IN READING

| NAME: | Robert E. Moreno III |

| SCHOOLS: | Glendale Community College; Northern Arizona University |

| MAJOR: | Communication Studies |

| CAREER GOAL: | Education field |

“One thing I find helpful is to write in the margins of my book and make side notes.”

Reading is something I’ve improved on greatly over the years, especially during my time at Glendale Community College (GCC). As a kid, I loved to read — it was fun. However, when I got to school, it became much more difficult. There was a lot to read! And in class they would make you read out loud. I always worried that my speech impediment would show. It wasn’t until I attended GCC that I gained confidence in my reading, found my voice, and started to speak out more.

When I first got to college, I realized two things about reading. First, I’d have to do a lot more reading than I ever did as a kid. And second, I wasn’t able to read things as quickly as the other students. However, I’ve implemented a few techniques to increase my reading speed and my retention of the material. One thing I find helpful is to write in the margins of my book and make side notes. If I don’t know a particular word, I look it up so I’ll understand what I’m reading. To increase my speed, I learned to first preview the chapter — to quickly look through the layout of the chapter, the headings, the pictures, and get an overall sense of what I’m going to read. Then I go back and fully read the chapter. This might take a little more time initially, but I found it’s a great way to understand what I’m reading.

Now when I read out loud, I take my time and control my breathing. This helps me control my stuttering and speak fluently. I’ve found that reading has helped me become not only a better speaker but also a better writer. And as someone with a speech impediment, I enjoy expressing my thoughts, ideas, and passion in writing for others to read.

YOUR TURN: Have you used any of the reading strategies Robert has used? If so, which ones? What benefits have these strategies provided for you? What challenges?