10.4 Stereotyping: The Cognitive Companion of Prejudice

We’ve explored some of the core causes of prejudice, but the social cognition perspective highlights the importance of beliefs that help promote, justify, and perpetuate prejudice. As you’ll recall from chapter 3, the knowledge that we have about a given category is stored in a cognitive structure called a schema. A stereotype is a cognitive schema containing all knowledge about and associations with a social group (Dovidio et al., 1996; Hamilton & Sherman, 1994). For example, our stereotype of the group librarians may contain our beliefs about the traits shared by members of that group (librarians are smart and well read), theories about librarians’ preferences and attitudes (e.g., librarians probably do not enjoy extreme sports), and examples of librarians we have known (Mr. Smith who sent me to the principal’s office in ninth grade). Whether or not we care to admit it, we all probably have stereotypes about dozens of groups, including lawyers, gays, lesbians, truckers, grandmothers, goths, Russians, immigrants, and overweight individuals.

People around the globe often openly endorse certain stereotypes about various groups, but because cultures typically promote stereotypes, even people who explicitly reject the validity of stereotypic beliefs may have formed implicit associations between groups and the traits their culture attributes to those groups. At a conscious level, you might recognize that not all librarians, if any at all, fit the mold of being bookish, uptight women who wear glasses. But simply hearing the word librarian is still likely to bring to mind all of these associated attributes without your being aware of it.

369

Finally, although we commonly refer to stereotyping as having false, negative beliefs about a group or applying such beliefs to an individual, it should be clear from the librarian example that stereotypes don’t have to be exclusively negative. They don’t even have to be entirely false. Being well read is a pretty positive trait, and the average librarian probably has read more than your average nonlibrarian. But even if we grant this possible difference in averages of these two groups, the assertion that all librarians are better read than all nonlibrarians is certainly false. So stereotyping goes awry when we overgeneralize a belief about a group to make a blanket judgment about every member of that group.

Moreover, even though some stereotypes are positive, this doesn’t mean that positive stereotyping can’t have negative effects. For example, stereotypes that celebrate outgroup members’ positive attributes can sometimes keep such people in a subordinate position, for example, when men celebrate women’s “supportive” nature (Glick et al., 1997). Stereotypes can be benevolent on the surface but ultimately patronize the stereotyped group and allow others to justify their underprivileged status. Before we get further into the negative consequences of stereotyping, let’s begin by exploring where stereotypes come from.

Where Do People’s Stereotypic Beliefs Come From?

The cultural perspective provides insight into where stereotypes come from. We learn them over the course of socialization as they are transmitted by parents, friends, and the media. Even small children have been shown to grasp the prevailing stereotypes of their culture (e.g., Aboud, 1988; Williams et al., 1975). In fact, it might be best to think about stereotypes as existing within the culture as well as within individuals’ minds. People who don’t endorse or actively believe stereotypes about other ethnic groups can still report readily on what those cultural stereotypes are (Devine, 1989). So even if we try not to accept or endorse stereotypes ourselves, we are likely to learn cultural stereotypes through prior exposure. For example, people who watch more news programming (which tends to overreport crime by minority perpetrators) are more likely to perceive Blacks and Latinos in stereotypic ways as poor and violent (Dixon, 2008a, 2008b; Mastro, 2003). This process of social learning explains how an individual picks up stereotypes both consciously and unconsciously. But how do these beliefs come to exist in a culture in the first place?

A Kernel of Truth

Let’s start with an idea Allport labeled the kernel of truth hypothesis. Even when stereotypes are broad overgeneralizations of what a group is like, some (but not all) stereotypes may be based on actual differences in the average traits or behaviors associated with two or more groups. This is what Allport meant by a “kernel of truth.” But even though this kernel might be quite small, with much more overlap between groups than there are differences, as perceivers we tend to exaggerate any differences that might exist and apply them to all members of the group. Lee Jussim and colleagues (2009) have been particularly active in trying to distinguish stereotypes with some degree of accuracy from those with none. Stereotypes that have some accuracy tend to be those that have to do with specific facts; for example, African Americans tend to be poorer than European Americans.

370

But when it comes to personality traits, there is little if any support for the kernel of truth hypothesis. Consider an impressive set of studies by Robert McCrae and colleagues (Terracciano et al., 2005). They assessed the actual personalities of samples from almost 50 nations and then assessed the stereotypes about the personalities of people from those nations. There was good agreement across nations about what each nationality is like (e.g., Italians, Germans, Americans). But the researchers found no correspondence between these stereotypes and the actual personalities of the people in those nations! You might think that Germans are more conscientious than Italians, but there’s no evidence from the personality data that this is actually the case.

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Gender Stereotypes in Animated Films, Then and Now

Gender Stereotypes in Animated Films, Then and Now

What are the most memorable movies from your childhood? Have you ever stopped to think about how those stories might have laid a foundation for the gender stereotypes you hold today? Children become aware of their own gender and begin showing a preference for gender-

Consider some popular children’s movies. Especially for little girls, movies about princesses capture the imagination, but many parents, educators, and cultural critics have questioned the messages these movies convey about women (e.g., Shreve, 1997). In the classic 1959 film Sleeping Beauty, the protagonist, Aurora, pretty and kind, cannot even regain consciousness without the love and assistance of her prince (Disney & Geronimi, 1959). Snow White cheerily keeps house and cleans up after the seven dwarfs in the 1937 animated film (Disney & Hand, 1937) before her status is elevated through marriage to a prince. Cinderella, released in 1950, feels more obviously oppressed by the forced domestic labor and humiliation by her stepmother and stepsisters, but again she can only escape her fate through the love of a wealthy prince (Disney et al., 1950).

The common theme in these pre–

There have been some more positive trends in the princess films that have been released more recently. Reflecting cultural shifts that encourage greater agency in women, princess characters have become noticeably more assertive. Ariel, from The Little Mermaid (Ashman et al.,1989), is willful and adventurous, eager to explore the world beyond her ocean home. But even so, she needs the permission of her authoritative father and the love of a man to realize her dreams. Along the way, she even trades her talent (her voice) to undergo severe changes to her body (legs instead of a tail) for the opportunity to woo her love interest.

In other modern animated films, the portrayals of princesses have become more complex and counterstereotypic. First, there has been an effort to present characters from different cultures, with protagonists who are Middle Eastern (Jasmine in Aladdin, 1992), Native American (Pocahontas, 1995), Chinese (Mulan, 1998), African American (Tiana, The Princess and the Frog, 2009), and Scottish (Merida, Brave, 2012). Although these films provide children a broader view of human diversity, they have also been criticized for their sometimes stereotypic portrayals of people from other cultures. For example, a line in the opening song to Aladdin originally described the Middle East as a place “where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face.”

Second, the modern princesses in animated films are more often cast as heroic. In Mulan, the protagonist disguises herself as male so that she can use her fighting skills to save and rescue the male characters in the movie. In Tangled, the resourceful protagonist openly mocks the outdated notion that she needs a prince to save her. Through her own wits and resources, Tiana manages to fulfill her dream of being a business owner. And most recently, Frozen tells the story of two strong and determined sisters. Elsa, the older sister, embraces her power to control ice even while fearing that her strength separates her from others, whereas her little sister Anna bravely risks her own life to find and save Elsa. These newer princess stories highlight autonomy, strength, and independence for young women.

Of course, before we get too encouraged by these messages of equality, we might ponder whether these modern fairy tales reflect lower levels of hostile sexism toward women (gone are the evil witches and stepmothers in these more contemporary films) but still reinforce benevolent sexist beliefs about women. The female characters are still young, beautiful, and good, and their Happily Ever After still often involves getting the guy.

In fact, these benevolent views of women are manifested in children’s movies more generally—

It’s likely that these stereotypic portrayals shape our gender schemas. A meta-

A complicating factor with the kernel of truth hypothesis is that even when facts seem to support a stereotype about a group, those facts don’t necessarily imply trait differences. For example, it may be true that a disproportionate percentage of African American males are convicted of crimes. However, this does not mean it is accurate to conclude that African Americans are more violent or immoral by nature. In most cultures, minority groups that are economically disadvantaged and the targets of discrimination are more likely to get in trouble with the law. Minority-

371

Social Role Theory

If stereotypes don’t arise from real differences in the underlying traits of different groups, where do they come from? One possibility is that they come from the roles and behaviors that societal pressures may impose on a particular group. You have read enough of this textbook so far to realize that cultural and social influences on the big, broad stage of the world often give us a script to read from and a character to play. Given what you know about the fundamental attribution error, you should not be surprised that when people see us in a role, they jump to the conclusion that we have the traits implied by the behaviors we enact in that role. This is the basic assumption of Alice Eagly’s social role theory (Eagly, 1987): We infer stereotypes that describe who people are from the roles that we see people play.

372

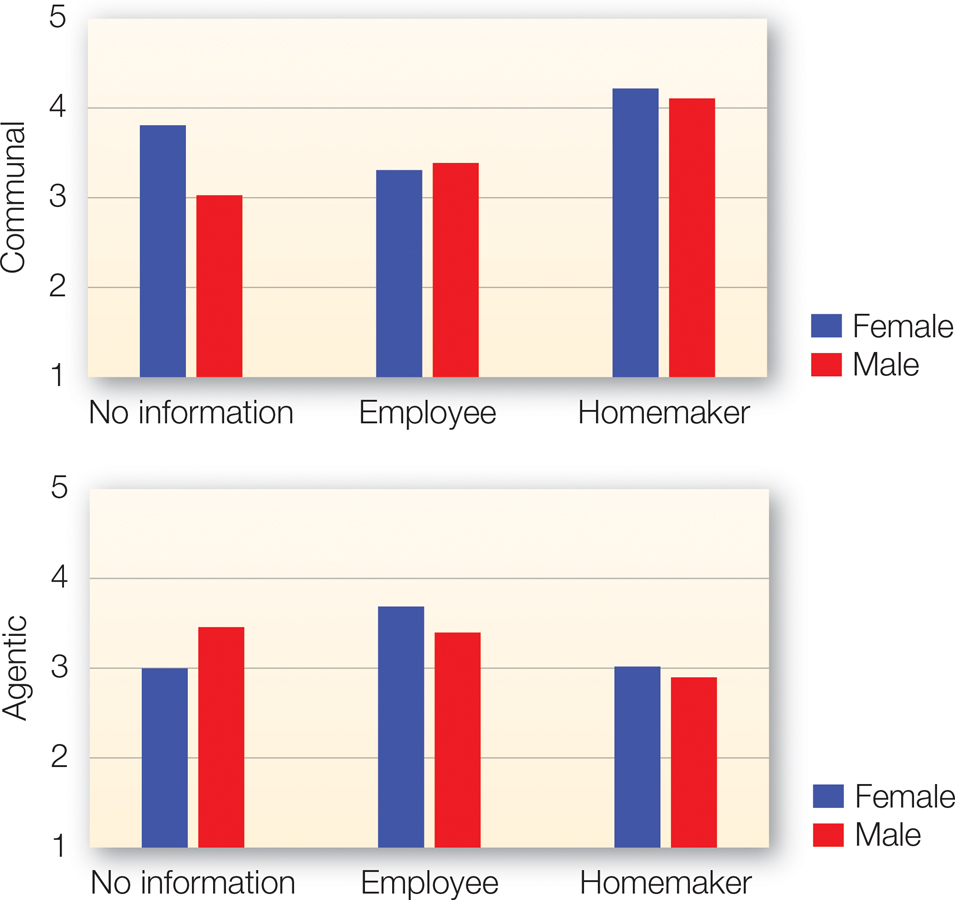

FIGURE 10.8

How Social Roles Can Determine Stereotypes

(a) With no other information, people assume that women are more communal than men and that (b) men are more agentic than women. But social roles might explain these stereotypes: Homemakers (either male or female) are assumed to be more communal than employees, and employees (either male or female) are assumed to be more agentic.

[Data source: Data from Eagly & Steffen (1984)]

A personal anecdote illustrates this problem. Recently, your current author was driving with a friend past a construction site, and we noticed that most of the workers were Hispanic. My friend said, “Hispanic people are very hard-

Social role theory primarily has been used to explain the existence of strong and persistent stereotypes about men and women. Men are stereotyped to be agentic—assertive, aggressive, and achievement oriented. Women are stereotyped to be communal—warm, empathic, and emotional. Are these stereotypes supported by gender differences in behavior? Yes. Men are more likely to be the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. Women are more likely to be the primary caregivers of children. If we look only at these statistics, we will find more than a kernel of truth to the stereotype. But does this gender segregation in the boardroom and at the playground really imply sex differences in traits? Not so fast. FIGURE 10.8 shows what happened when people were asked to rate the traits listed in a brief description of an average man or an average woman, with either no information about the person’s occupation, information that he or she was a fulltime employee, or information that he or she was full-

The moral here is that social roles play a large part in shaping our stereotypes. But because social pressures can shape the roles in which various groups find themselves, differences in stereotypes follow suit. The traditional stereotype of African Americans as lazy and ignorant was developed when the vast majority of them were slaves. At that time in the South, it was actually illegal to educate African Americans, and so it was hardly a matter of the slaves’ personal preference that they would be relatively ignorant. Nor would it be surprising that they were not particularly enthused to do work that was forced on them. Similarly, Jews have been stereotyped as money hungry or cheap, a stereotype that developed in Europe at a time when Jews were not allowed to own land. As a consequence, Jews needed to become involved in trade and commerce in order to survive economically. The particular stereotypes attached to groups are often a function of these historical and culturally embedded social constraints.

373

The Stereotype Content Model

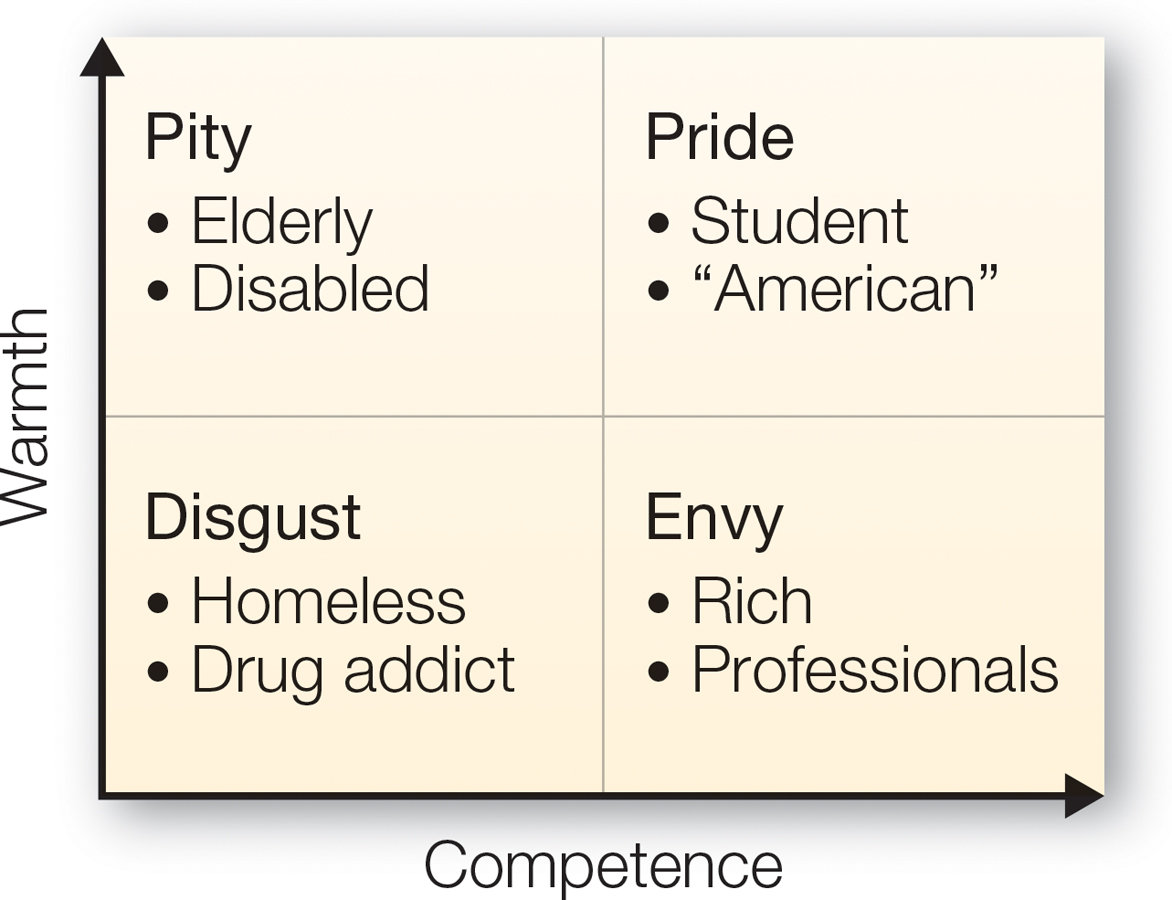

FIGURE 10.9

The Stereotype Content Model

According to the stereotype content model, the stereotypes we have of different groups can range along two dimensions of competence and warmth. As a result, we have different emotional reactions to different types of groups.

[Data source: Fiske et al. (2002)]

The stereotype content model extends the basic logic of social role theory by positing that stereotypes develop on the basis of how groups relate to one another along two dimensions (Fiske et al., 2002). The first is status: Is the group perceived as having relatively low or high status in society, relative to other groups? The second is cooperation in a very broad sense that seems to encompass likeability: In a sense, is the group perceived to have a cooperative/helpful or a competitive/harmful relationship with other groups in that society?

The answers to these questions lead to predictions about the traits that are likely to be ascribed to the group. With higher status come assumptions about competence, prestige, and power, whereas lower status leads to stereotypes of incompetence and laziness. Groups that are seen as cooperative/helpful within the society are seen as warm and trustworthy, whereas groups that are competitive/harmful within the larger society are seen as cold and conniving. These two dimensions of evaluation, warmth and competence, have long been acknowledged to be fundamental to how we view others. Within this theory, we can see how they translate into distinct stereotypes: Status determines perceived competence, whereas cooperativeness/helpfulness determines perceived warmth. Consider that these dimensions are largely independent, and we see that stereotypes can cluster together in one of four quadrants in a warmth-

In an interesting finding, groups whose stereotypes fit into one of these quadrants tend to elicit different types of emotional responses (Cuddy, Fiske et al., 2007). Groups that are stereotyped as personally warm but incompetent (e.g., the elderly and physically disabled) elicit pity and sympathy. Groups perceived as low in warmth but high in competence (e.g., rich people, Asians, Jews, minority professionals) elicit envy and jealousy. Groups stereotyped in purely positive terms as both warm and competent tend to be ingroups or groups that are seen as the cultural norm in a society. To the degree that these groups are valued, they generally elicit pride and admiration. Finally, groups stereotyped in purely negative terms as both cold and incompetent (e.g., homeless people, drug addicts, welfare recipients) elicit disgust and scorn.

Illusory Correlations

Social role theory and the stereotype content model both assume that structural factors put groups in different roles that encourage role-

Illusory correlation

A tendency to assume an association between two rare occurrences, such as being in a minority group and performing negative actions.

These kinds of illusory correlations occur under very specific circumstances—

374

Why Do We Apply Stereotypes?

Now that we understand a little more about where stereotypes come from, we turn to the question of why we apply and maintain them. The fact that stereotypes exist and persist, even when facts seem to disconfirm them, suggests that they must serve some kind of psychological function. Indeed, research reveals that stereotypes have five primary psychological functions. Let’s consider each of them.

1. Stereotypes Are Cognitive Tools for Simplifying Everyday Life

In his dialogue Phaedrus, Plato depicts Socrates’ famous description of the human need to “carve nature at its joints.” What Plato (and by extension, Socrates) meant was that simply perceiving the many varieties of things in the world is a challenge. Concepts and theories help us sort through this variety and categorize things into meaningful, if not natural, kinds. Even if we restrict our view to the social world, can we truly perceive every person we see, encounter, or interact with solely on the basis of their individual qualities, characteristics, and behaviors?

People rely on stereotypes every day because they simplify this process of social perception. Stereotypes allow people to draw on their beliefs about the traits that characterize typical group members to make inferences about what a given group member is like or how he or she is likely to act. Imagine you have two neighbors, one a librarian and the other a veterinarian. If you had a book title on the tip of your tongue, you would more likely consult the librarian than the vet—

The idea that stereotypes are mental heuristics that we fall back on to save time in social perception has been turned into a tongue-

And if stereotypes simplify impression formation, using them should leave people with more cognitive resources left over to apply to other tasks. To test this, researchers (Macrae et al., 1994) showed participants a list of traits and asked them to form an impression of the person being described. In forming these impressions, people were quicker and more accurate if they were also given each person’s occupation. It’s easier to remember that Julian is creative and emotional if you also know he is an artist, because artists are stereotyped as possessing those characteristics. But having these labels to hang your impression on also frees up your mind to focus on other tasks. In the study, this other task was an audio travelogue about Indonesia that participants were later tested on. Those who knew the occupations of the people they learned about while they were also listening to the audio travelogue not only remembered more about the people but also remembered more about Indonesia. The researchers concluded that stereotypes are “energy-

375

2. Stereotypes Justify Prejudices

Stereotypes aren’t mere by-

According to the justification suppression model of prejudice expression (Crandall & Eshleman, 2003), people endorse and feel free to express stereotypes in part to justify their own negative affective reactions to outgroup members. In other words, stereotypes can provide people with supposedly acceptable explanations for having negative feelings about a group. If, for example, a person stereotypes all Hispanics as aggressive, then she can justify why she feels frightened around Hispanics. From this perspective, the negative feelings sometimes come first, and the stereotypes make those feelings seem acceptable, even rational.

Justification suppression model

The idea that people endorse and freely express stereotypes in part to justify their own negative affective reactions to outgroup members.

To test this idea, Chris Crandall and colleagues (2011) set up a situation in which they induced people to have a negative feeling toward a group prior to forming a stereotype about that group. They did this through an affective conditioning method, which essentially involves repeatedly pairing a novel stimulus with negative words or images (e.g., sad faces) that didn’t imply any specific traits associated with the group. In this way, some participants were led to have a negative affective association toward a group that they had never heard of—

3. Stereotypes Help Justify Violence and Discrimination Against Outgroups

Dehumanization

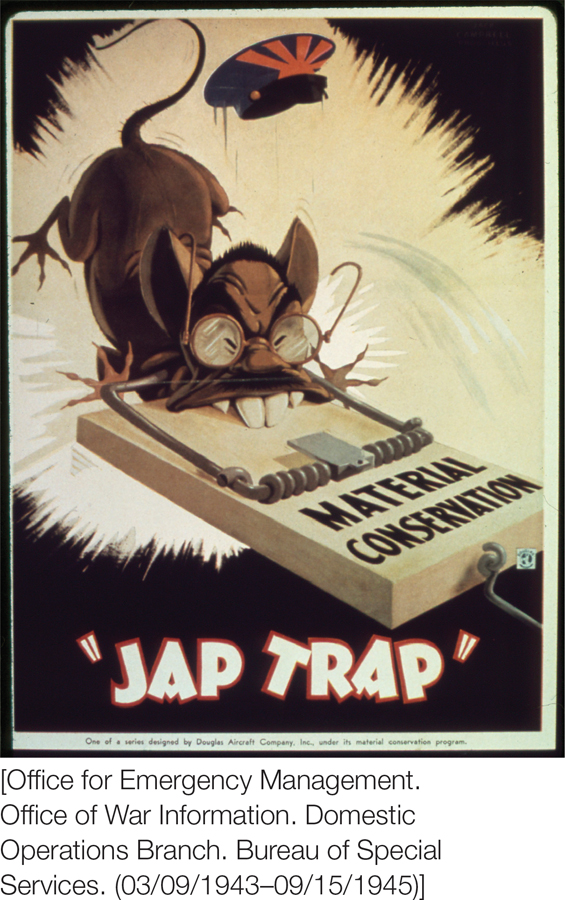

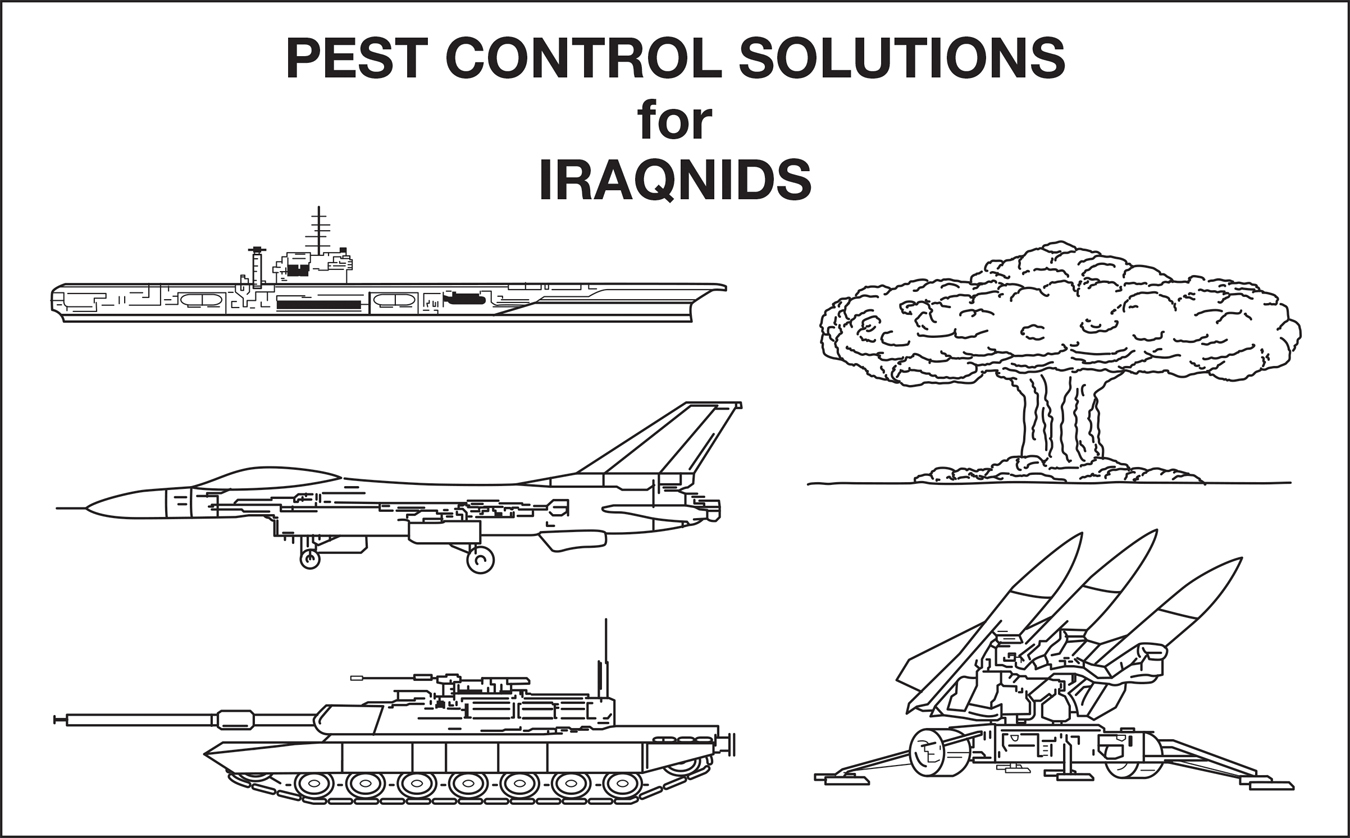

FIGURE 10.10a

Dehumanizing the Outgroup

This World War II–

Dehumanization is the tendency to view out-

Dehumanization

The tendency to hold stereotypic views of outgroup members as animals rather than humans.

FIGURE 10.10b

Dehumanizing the Outgroup

This flyer, circulated among American troops during the first Persian Gulf war, dehumanized people from Iraq.

FIGURE 10.11

Similarities?

What is the relationship between cognitive dissonance and dehumanization?

376

War enemies and prospects for genocide are not the only outgroups compared with animals. According to Goff and colleagues (2008), White Americans have for many years equated Black Americans to monkeys and apes. In FIGURE 10.11, the image to the left is a propaganda poster used to recruit American soldiers during World War I by portraying Germans as savage apes ruled by animal instincts for sex and aggression. The image on the right is of LeBron James, the first African American male to grace the cover of Vogue magazine. Notice any similarities?

Goff and colleagues proposed that, even if White Americans are not consciously aware that they associate African Americans with aggressive apes, they have learned this stereotype from their surrounding culture. In one study supporting this claim, White Americans were more likely to hold the opinion that violence against a Black crime suspect was justified if they had been primed with ape-

The tendency to think about outgroups as nonhuman animals has likely played a role in fueling and justifying intergroup conflict across cultures and historical epochs. This is because it creates a vicious cycle of prejudice and violence against out-

Once the outgroup has been reduced to animals who do not deserve moral consideration, the perpetrators feel less inhibited about committing further violence (Kelman, 1976; Opotow, 1990; Staub, 1989). After all, it is easier to hurt or kill rats, bugs, and monkeys than to hurt and kill fellow human beings. Indeed, in one study, people were more likely to administer a higher intensity of shock to punish people described in dehumanizing (i.e., animalistic) terms than people described in distinctively human terms (Bandura et al., 1975). This perpetuates the cycle, leading in-

Infrahumanization

A more subtle form of dehumanization is infrahumanization (Leyens et al., 2000). When people infrahumanize outgroup members, they do not compare them directly with nonhuman animals. Rather, they perceive those outgroup members as lacking qualities viewed as unique to human beings. These qualities include language and rational intelligence, as well as complex human emotions such as hope, humiliation, nostalgia, and sympathy. People attribute these uniquely human emotions to members of their ingroup, but they are reluctant to believe that outgroup members also experience those sophisticated emotions, again because they see the outgroup as less human than their own ingroup. By contrast, people tend to attribute similar levels of the more basic emotions such as happiness, anger, and disgust to both the ingroup and the outgroup (Gaunt et al., 2002; Leyens et al., 2001).

Infrahumanization

The perception that outgroup members lack qualities viewed as unique to human beings, such as language, rational intelligence, and complex social emotions.

377

Infrahumanization has important repercussions for people’s treatment of outgroup members. Cuddy and colleagues (2007) looked at people’s desire to help with relief efforts in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which caused massive destruction to parts of the southeastern United States in 2005. Participants in their study were less likely to infer that racial outgroup members who suffered from the hurricane were experiencing uniquely human emotions, such as remorse and mourning, than were racial ingroup members. The more participants infrahumanized the hurricane victims in this way, the less likely they were to report that they intended to take actions to help those individuals recover from the devastation.

Sexual Objectification

Women as a group are subject to a specific form of dehumanization known as sexual objectification, which consists of thinking about women in a narrow way, as if their physical appearance is all that matters. Based on the work of early theorists such as the psychoanalyst Karen Horney and the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-

Sexual objectification

The tendency to think about women in a narrow way as objects rather than full humans, as if their physical appearance is all that matters.

Objectification theory

Theory proposing that the cultural value placed on women’s appearance leads people to view women more as objects and less as full human beings.

In assessing this idea, researchers found that well-

Utilizing the neuroscience perspective, Mina Cikara and colleagues (Cikara et al., 2011) found that men who were higher in hostile sexism (expressed as a negative attitude toward women’s efforts to achieve gender equality) showed decreased activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) when viewing scantily clad and provocatively posed (and thus sexualized) female targets, but not fully clothed (non-

Objectification of women can help justify exploitation and poor treatment of them. Integrating objectification theory and terror management theory, Jamie Goldenberg and colleagues proposed that objectification also may help people avoid acknowledging the fact that we humans are animals and therefore mortal (e.g., Goldenberg et al., 2009). Portraying women in an idealized (often airbrushed) way and only as objects of beauty or sexual appeal reduces their connection to animalistic physicality. (After all, not too many other mammals wear makeup, use perfume, and get breast implants!) Supporting this view, Goldenberg and colleagues have shown that reminding both men and women of their mortality, or of the similarities between humans and other animals, increases negative reactions to women who exemplify the creaturely nature of the body: women who are menstruating, pregnant, or breast-

378

In one such study, male and female participants reminded of their mortality or primed with a control topic were told to set up some chairs for an interaction task with another partner who was currently in an adjacent room either breast-

4. Stereotypes Justify the Status Quo

Stereotypes don’t justify only our emotions and behavior, they also justify the status quo. Earlier, we talked about the stereotype content model and the finding that across cultures, the status position of a group seems to determine stereotypes about competence, whereas the cooperativeness of a group seems to determine stereotypes about warmth (Cuddy et al., 2008). Another finding from this cross-

According to system justification theory, these complementary or ambivalent stereotypes help maintain the status quo (Jost & Banaji, 1994). We discussed this a bit back in chapter 9, but let’s expand on it here. System justification theory proposes that people largely prefer to keep things the way they are. So from this perspective, stereotypes justify the way things are. In some ways this is the flip side of social role theory: We not only assume the traits people have by the roles they enact, but we also assert that they should be in those roles because they have the traits that are needed for those roles.

System justification theory suggests that those who have status and power in a society will often come to view those without power and status as being less intelligent and industrious than their own group, as a way to justify their own superior economic and political position. If advantaged members of a society didn’t generate these justifications, then they would have to admit that deep injustices exist that they should all be working to rectify. Yes, disadvantaged groups would benefit from these efforts—

This motivation to justify the system can sometimes trump people’s motivations to have the best outcomes for themselves and their ingroup. Although those in higher-

How do these complementary stereotypes play into the motivation to justify existing status differences among groups? By favoring complementary or ambivalent stereotypes, groups that are disadvantaged in terms of their status in society can still pride themselves on their warmth or morality. With that positive stereotype in your back pocket, the negative stereotypes don’t seem so bad. Similarly, groups with power and status can assuage any guilt they might feel about their advantages in life by pointing to the warmth and purity of those without status. We see this most strikingly with gender. Modern theories of gender bias point to ambivalent sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996). This pairs hostile beliefs about women (that women are incompetent or push too hard for gender equality) with benevolent beliefs (that women are pure and more compassionate than men). What effect do these messages have? When women are primed to think about hostile sexism, they are more motivated to engage in collective action to change gender inequality. But when they are primed with benevolent sexism, they are not (Becker & Wright, 2011).

Ambivalent sexism

The pairing of hostile beliefs about women with benevolent but patronizing beliefs about them.

379

Research also suggests that we prefer outgroup members to conform to the prevailing stereotypes. Women who are assertive and direct are often judged negatively, whereas the same actions by men lead to admiration (Rudman, 1998). In similar findings, terror management researchers (Schimel et al., 1999) have shown that reminding people of their mortality, which motivates people to want their worldviews upheld, leads white heterosexual Americans to prefer Germans, African Americans, and gay men who conform to prevailing American stereotypes of these groups over those who behave counterstereotypically.

5. Stereotypes Are Self-esteem Boosters

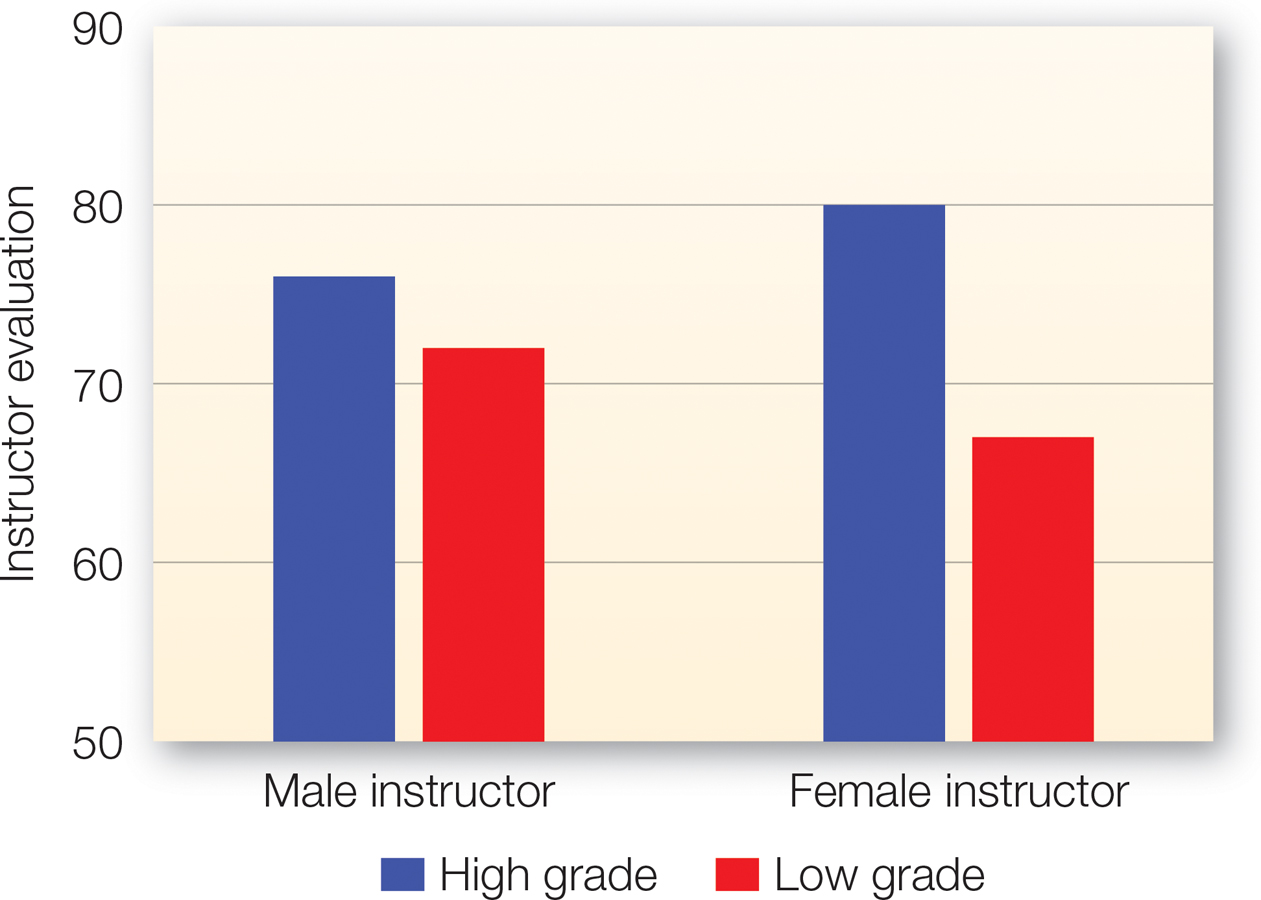

FIGURE 10.12

Self-

Although student evaluations of male and female instructors are equivalent among students who perform well, students who receive a lower grade rate female instructors as less competent than male instructors.

[Data source: Sinclair & Kunda (1999)]

As described previously, self-

Research by Lisa Sinclair and Ziva Kunda (1999) shows that we selectively focus on different ways of categorizing people, depending on these self-

Further research suggests that once activated, these stereotypes likely bias people’s judgments. For example, female and male faculty members receive similar course evaluations from students who do well in their courses, but students who receive lower grades evaluate female instructors as less competent than their male peers (FIGURE 10.12) (Sinclair & Kunda, 2000).

How Do Stereotypes Come Into Play?

Think ABOUT

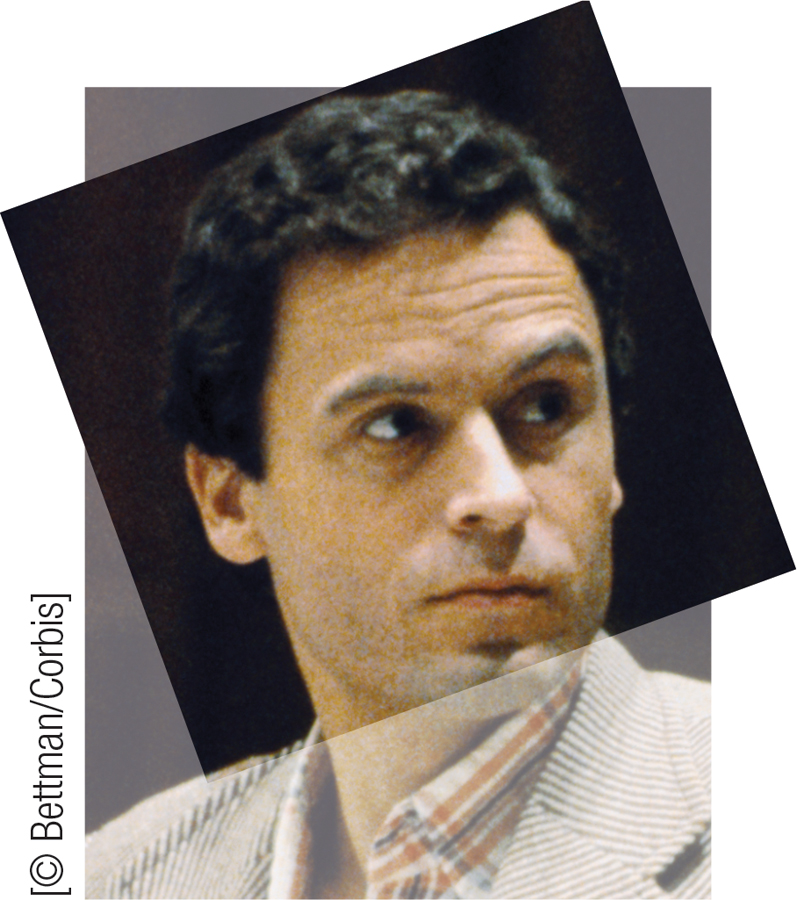

So far, we have covered where stereotypes come from and why we tend to rely on them. But how do they actually work? Take a look at the guy in the photo. What’s your impression of him? How did you form that impression? You might see the jacket, collared shirt, and neatly trimmed hair and think he’s a young, attractive, professional man. You’ve just categorized him on the basis of age, appearance, educational level, and gender. He looks to be White, so we can throw a racial categorization in as well. From this, you are likely to activate some relevant stereotypes—

380

Unfortunately, many young women did just that. They categorized him just as you probably did. They had no way of knowing one additional group he belonged to—

Research has delved into the process by which we initially categorize a person as belonging to a group, activate stereotypes associated with that group, and then apply those stereotypes in forming judgments of that person. Let’s learn more about how this process works.

Categorization

In the process of “carving nature at its joints,” we categorize everything—

But the categorization process isn’t entirely objective. It’s also influenced by our stereotypes and prejudices (Freeman & Ambady, 2011). For example, to the degree that people tend to stereotypically associate young Black men with anger, they are quicker to categorize an angry face as being Black if the person’s race is rather ambiguous. Similarly, mixed-

Regardless of how we come to categorize a person as a member of an outgroup, once we do, we tend to view that person in stereotypic ways. One reason this happens is that the very act of categorizing makes us more likely to assume that all members of the outgroup category are alike. Merely by categorizing people into outgroups, we tend to view those individuals as more similar to each other—

Outgroup homogeneity effect

The tendency to view individuals in outgroups as more similar to each other than they really are.

The primary explanation for the outgroup homogeneity effect is that we are very familiar with members of our own group and therefore tend to see them as unique individuals. We have less detailed knowledge about members of outgroups, so it’s easier simply to assume they are all alike. In addition, we often know outgroup members only in a particular context or role. For example, a suburban White American might know African Americans mainly as sports figures, hiphop artists, and criminals on TV. This role-

381

Let’s see how this has been demonstrated in a couple of classic studies. In one demonstration, psychologists (Quattrone & Jones, 1980) asked university students to watch a video of a student from the participant’s own university or from a different university make a decision (e.g., between listening to rock or classical music). The participants were then asked to estimate what percentage of people from that person’s university would make the same decision. They estimated that a higher percentage of the person’s fellow students would have the same musical preference when he was from a different university rather than the participants’ own. So when you assume that “they are all alike,” you can infer that what one likes, they all like, but you probably also like to believe that “we” are a diverse assortment of unique individuals.

The outgroup homogeneity effect not only extends to the inferences we make about a person’s attitudes but also leads to very real perceptual confusions. We actually do see outgroup members as looking more similar to each other, a phenomenon that can have very profound consequences for the accuracy of eyewitness accounts (Wells et al., 2006). This type of perceptual bias was first illustrated in a series of studies in which participant ingroup and outgroup members interacted in a group discussion (Taylor et al., 1978). When later asked to remember who said what—

Stereotype Activation

After we make an initial categorization, the stereotypes that we associate with that category are often automatically brought to mind. Before addressing the way in which these stereotypes can bias our subsequent judgments and behavior, let’s dig a little deeper into how this activation works. In all of this work, we rely on some of the basic assumptions about schemas and schematic processing that we covered back in chapter 3.

One assumption is that stereotypes can be activated regardless of whether or not we want them to be activated. Sure, some folks have blatant negative beliefs about others that they are happy to bend your ear about. Others want to believe that they never ever, ever judge people on the basis of stereotypes. Most of us probably are somewhere in the middle. But regardless, individuals raised and exposed to the same cultural information all have knowledge of which stereotypes are culturally associated with which groups (Devine, 1989). This information has made it into those mental file folders in our head, even if we have tried to flag it as false and malicious. When we meet someone from Wisconsin, we mentally pull up our Wisconsin folder on the state to be better prepared for discussing the intricacies of cheese making and the Green Bay Packers. We do this unconsciously and without intending to—

382

Patricia Devine (1989) provided an early and influential demonstration of automatic stereotype activation. She reasoned that anything that reminds White Americans of African Americans would activate the trait aggressive because it is strongly associated with the African American stereotype. To test this hypothesis, she exposed White participants subliminally to 100 words. Each word was presented so briefly (for only 80 milliseconds) that participants could not detect the words and experienced them as mere flashes of light. Depending on which condition participants were in, 80 or 20% of the words—

Then, as part of an apparently separate experiment, participants read a paragraph describing a person named Donald, who behaved in ways that could be seen as either hostile or merely assertive. Participants primed with the Black stereotype interpreted Donald’s ambiguous behaviors as more hostile than did those who didn’t get this prime. Even though aggressive was not primed outright, because it is part of the stereotype schema for African Americans, priming that stereotype cued people to perceive the next person they encountered as being aggressive. In later studies, this type of priming even led participants to act more aggressively toward an unsuspecting person (Bargh et al., 1996).

In an important finding, this effect was the same for those who report low and high levels of prejudice toward African Americans. However, it is important to clarify that Devine’s study primed people directly with stereotypes about Blacks, not simply with the social category “Blacks” or a photo of a Black individual. Other research suggests some people are less likely to activate stereotypic biases automatically. First, Lepore and Brown (1997) showed that people with stronger prejudices activate a negative stereotype about Blacks when they are simply exposed to the category information (i.e., the word Blacks), whereas those who are low in prejudice don’t show this activation at all.

In addition, newer research suggests that the goal of being egalitarian can itself be implicitly activated when people encounter an outgroup and can help keep negative stereotypes from coming to mind (Moskowitz, 2010; Moskowitz & Li, 2011; Sassenberg & Moskowitz, 2005). The take-

How Do Stereotypes Contribute to Bias?

Once stereotypes are activated, we use them to perceive and make judgments about others in ways that confirm, rather than disconfirm, those stereotypes. Stereotypes influence information processing at various stages, from the first few milliseconds of perception to the way we remember actions years from now. And because stereotypes can be activated automatically, even people who view themselves as nonprejudiced can sometimes inadvertently view group members through the lens of negative stereotypes. Let’s take a whirlwind tour of some of the ways that stereotypes color people’s understanding of others. In doing so, we’ll explore not just how research has examined these biases but also how they help provide insight into very real social consequences for those on the receiving end of negative stereotypes.

APPLICATION: Stereotypes Influence Perception

|

APPLICATION: |

| Stereotypes Influence Perception |

Just after midnight on February 4, 1999 four New York City police officers were in pursuit of a serial rapist believed to be African American. They approached a 23-

383

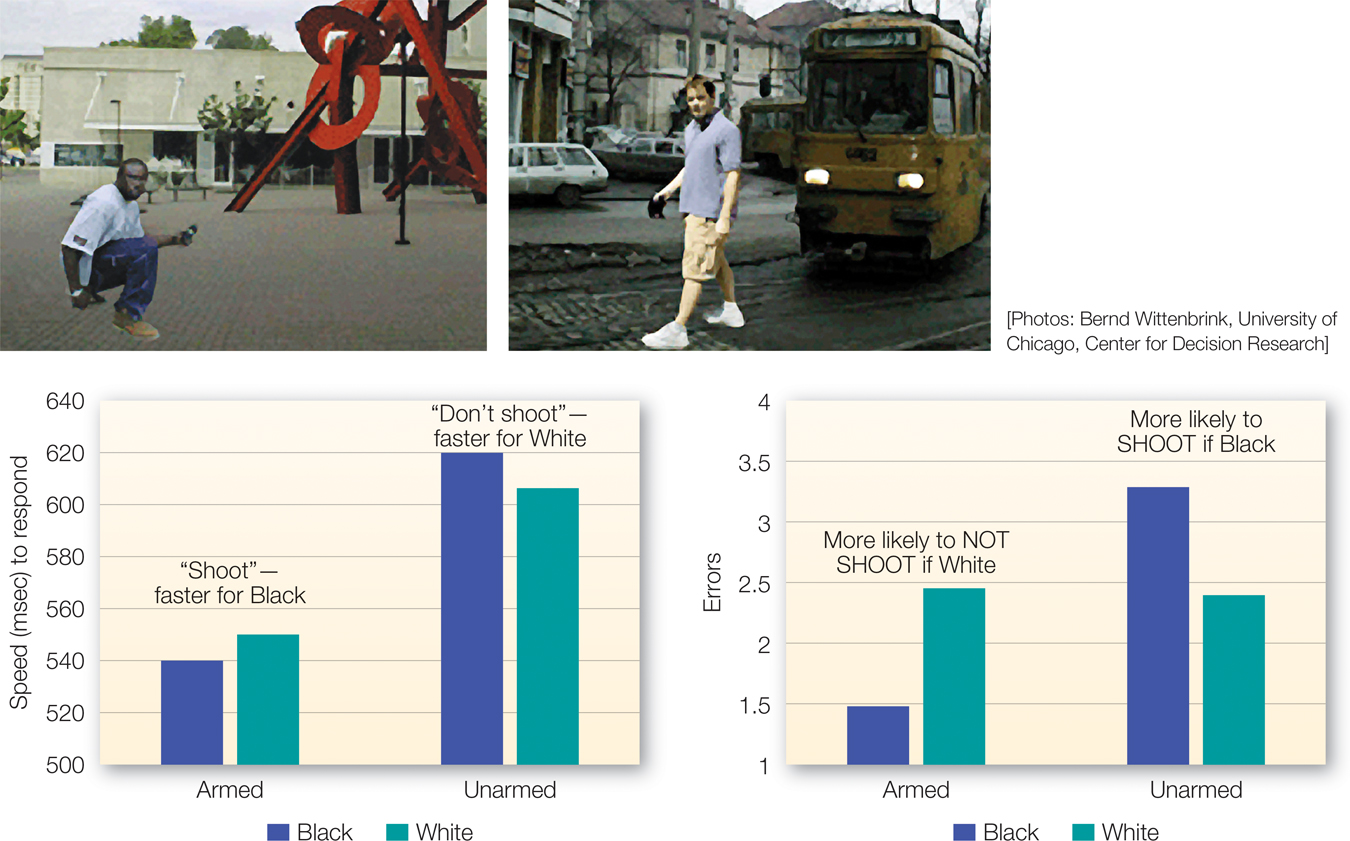

Yes. In fact, this event inspired a line of research on what has come to be called the shooter bias. This bias has to do with the stereotyped association of Blacks with violence and crime (e.g., Payne, 2001; Eberhardt et al., 2004). We know that people process stereotype-

Shooter bias

The tendency to mistakenly see objects in the hands of Black men as guns.

FIGURE 10.13

The Shooter Bias

In studies that document the shooter bias, participants play a video game in which they are instructed to shoot at anyone who is armed but to avoid shooting anyone who is unarmed.

The experimenters predicted that White participants would be faster to shoot an armed person if he were Black rather than White. In addition, they should be faster to make the correct decision to not shoot an unarmed person if he was White rather than Black. The bar graph on the left in FIGURE 10.13 shows that this is just what happened. When in another study (shown in the right graph of FIGURE 10.13), particpants were forced to make decisions under more extreme time pressure, they made the same kind of error that the police made when they shot Diallo. That is, participants were more likely to shoot an unarmed man who was Black rather than White. Evidence from these studies suggests that these effects resulted more from the individual’s knowledge of the cultural stereotype that Blacks are dangerous than from personal prejudice toward Blacks. In fact, in a follow-

384

Follow-

Law-

Interpreting Behavior

If stereotypes actually can lead us to sometimes see something that isn’t there, it should come as no surprise that they also color how we interpret ambiguous information and behaviors (e.g., Kunda & Thagard, 1996).

Research shows that people interpret the same behavior differently when it is performed by individuals who belong to stereotyped groups. In one study (Duncan, 1976), White students watched a videotape of a discussion between two men. They were told that whenever they heard a beep, they were to classify the behavior they had just observed into one of several categories (e.g., gives information, asks for opinion, playing around, violent behavior). Gradually, the discussion got more passionate, and at one point one of the men shoved the other. Immediately after the shove, participants heard a beep telling them to interpret that behavior. Was the shove harmless horseplay, or was it an act of aggression? If participants (who were White) watched a version of the tape in which the man delivering the shove was White, only 17% described the shove as violent, and 42% said it was playful. However, if they watched a version in which the same shove was delivered by a Black man, 75% said it was violent, and only 6% said it was playful.

In fact, stereotypes influence the interpretation of ambiguous behaviors even when those stereotypes are primed outside of conscious awareness. When police and probation officers were primed beneath conscious awareness with words related to the Black stereotype, and then read a vignette about a shoplifting incident, they rated the offender as more hostile and deserving of punishment if he was Black, but not if he was White (Graham & Lowery, 2004).

Many other studies have similarly shown that stereotypes associated with race, social class, or profession can lend different meanings to the same ambiguous behaviors (e.g., Darley & Gross, 1983; Dunning & Sherman, 1997). Some of the evidence suggests that stereotypes set up a hypothesis about a person, but because we have a general bias toward confirming our expectancies, we interpret ambiguous information as evidence supporting that hypothesis.

385

The Ultimate Attribution Error

Stereotypes don’t only color our attention and our judgment of ambiguous information as we encounter it. They also bias our interpretation after events have played out. Recall from chapter 4 that when we make a dispositional attribution, we conclude that a person’s behavior was due to some aspect of his or her character or disposition. (“That guy in the Mustang cut me off because he’s a jerk!”) When we make a situational attribution, we do not make reference to disposition but instead conclude that the person’s behavior was due to some aspect of the situation. (“That guy in the Mustang cut me off because a dog ran onto the road.”)

You might also remember that we like to make self-

Ultimate attribution error

The tendency to believe that bad actions by outgroup members occur because of their internal dispositions and good actions by them occur because of the situation, while believing the reverse for ingroup members.

Of course, every now and again we might be forced to admit that an outgroup member performed well or behaved admirably and an ingroup member performed or behaved poorly. But now the attribution veers toward the situation. Not only does this error make the ingroup seem superior, it also reinforces negative stereotypes about the outgroup. It leads people to attribute stereotype-

The ultimate attribution error shapes, for example, how people make attributions for men’s and women’s behavior (e.g., Deaux, 1984). When men succeed on a stereotypically masculine task, observers tend to attribute that success to the men’s dispositional ability, but when women perform well on the same task, observers tend to attribute that success to luck or effort. Likewise, men’s failures on stereotypically masculine tasks are often attributed to bad luck and lack of effort, whereas women’s failures on the same tasks are attributed to their lack of ability. In this research, both men and women often exhibit this form of the ultimate attribution error: Regardless of their gender, people tend to explain men’s and women’s behaviors in ways that fit culturally widespread stereotypes.

The Linguistic Intergroup Bias

Group-

386

Research by Anne Maass and colleagues bears out these intuitions. When people talk about positive behaviors performed by their ingroup, they tend to use more abstract descriptions, whereas when they talk about positive behaviors performed by outgroup members, they tend to use more concrete descriptions. Again, this is because such descriptions imply that the positive behaviors are short-

Linguistic intergroup bias

A tendency to describe stereotypic behaviors (positive ingroup and negative outgroup) in abstract terms while describing counterstereotypic behaviors (negative ingroup and positive outgroup) in concrete terms.

Stereotypes Distort Memory

Finally, stereotypes bias how we attend to and encode information as well as what we recall or remember. Back in chapter 3, we described a study in which White participants were shown a picture of a Black man in a business suit being threatened by a young White man holding a straight razor (Allport & Postman, 1947). As that participant described the scene to another participant, who described it to another participant, and so on, the story tended to shift to the razor being in the Black man’s hand and the business suit being on the White man. Rumors often can distort the facts because our stereotypes bias what we recall (and what we retell) in ways that fit our expectations. Since that initial demonstration, similar findings have also been shown even when the stereotype isn’t evoked until after the information has been encoded, and for a wide range of stereotypes regarding ethnicity, occupation, gender, sexual orientation, and social class (e.g., Dodson et al., 2008; Frawley, 2008).

Summary: Stereotypes Tend to Be Self-confirming

The phenomena we’ve discussed are just a few of the many ways in which stereotypes systematically color the way we think and make judgments about other individuals and groups. A harmful consequence of this influence is that stereotypes reinforce themselves, making them relatively impervious to change (Darley & Gross, 1983; Fiske & Taylor, 2008; Rothbart, 1981). Stereotypes lead us to attend to information that fits those stereotypes and to ignore information that does not. When we do observe behaviors that are inconsistent with our stereotypes, we tend to explain them away as isolated instances or exceptions to the rule (Allport, 1954). Because stereotypes can be activated unconsciously, people may not even be aware that stereotypes are biasing what they perceive and how they explain it to themselves and to others. All they may know is that they have “seen” such and such behavior. They believe that their reactions to and interpretations of stereotyped individuals are free of prejudice because they assume that they are looking at the world objectively. The ironic fact is that the very meaning of others’ attributes and behaviors has already been filtered through the lenses of their stereotypes. When it comes to stereotypes, believing is seeing.

387

10.4.1

|

Stereotyping: The Cognitive Companion of Prejudice |

|

Stereotypes can help promote and justify prejudice, even if they are positive. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Where do stereotypes come from? A kernel of truth that is overblown and overgeneralized. Assumptions about group differences in traits inferred from group differences in social roles. Generalizations about a group’s warmth and competence that are based on judgments of cooperativeness and status. Illusory correlations that make unrelated things seem related. |

Why do we apply stereotypes? To simplify the process of social perception and to conserve mental energy. To justify prejudicial attitudes. To justify discrimination by dehumanizing, infrahumanizing, or objectifying others. To justify the status quo and to maintain a sense of predictability. To maintain and bolster self- |

How do stereotypes affect judgment? Categorization increases the perceived homogeneity of outgroup members, thereby reinforcing stereotypes. Stereotypes can be activated automatically, coloring how we perceive, interpret, and communicate about the characteristics and behaviors of outgroup (and ingroup) members. Stereotypes influence how we perceive and interpret behavior, as well as how we remember information. Because of these biases, stereotypes tend to be self- |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/