11.1 Prejudice From a Target’s Perspective

Perceiving Prejudice and Discrimination

The American tennis champion Arthur Ashe was very conscious of his position as the first Black man to break into a predominantly White sport.

If you are a member of a group that is viewed or treated negatively by the larger society in which you live, your membership in that group is bound to affect you in some way (Allport, 1954). Yet, as you learned in the previous chapter, for many stigmatized groups in the United States, prejudice can be a lot subtler and harder to detect than it was 50 years ago. To an optimist, this is a sign of progress. But from a more pessimistic perspective, this makes it harder to detect when one is the target of prejudice, even when prejudice significantly affects one’s thoughts and behavior. This is a dilemma that anyone who feels marginalized in society probably has faced. Take the following quote from Erving Goffman’s classic 1963 book Stigma: “And I always feel this with straight people [people who are not ex-

This individual’s reflection reveals the master status that can accompany stigmatizing attributes—

Master status

The perception that a person will be seen only in terms of a stigmatizing attribute rather than as the total self.

When people are conscious of being stigmatized, they become more vigilant to signs of prejudice. In one study, women expecting to interact with a sexist man were quicker to detect sexism-

Individual Differences in Perceiving Prejudice

As you might suspect, not all minority-

Members of minority groups also differ in their stigma consciousness, their expectation that other people—

Stigma consciousness

The expectation of being perceived by other people, particularly those in the majority group, in terms of one’s group membership.

391

People differ in their perceptions of prejudice, and although they sometimes might overestimate their experience of prejudice, this is not the norm. Instead, it is more common for people to estimate that they personally experience less discrimination than does the average member of their group (Taylor et al., 1990). This effect, called the person-

Person-group discrimination discrepancy

The tendency for people to estimate that they personally experience less discrimination than is faced by the average member of their group.

Motivations to Avoid Perceptions of Prejudice

People may fail to see the prejudice targeted at them because they are motivated to deny that prejudice and discrimination affect their lives. Why? For one thing, this denial may be part of a more general tendency to be optimistic. Experiencing discrimination, having health problems, and being at risk for experiencing an earthquake all are negative events, and people are generally overly optimistic about their likelihood of experiencing such outcomes (Lehman & Taylor, 1987; Taylor & Brown, 1988). It might be beneficial to one’s own psychological health to regard discrimination as something that happens to other people.

Another reason is that people may be motivated to sustain their faith that the way society is set up is inherently right and good, thereby justifying the status quo (Jost & Banaji, 1994). Buying into the status quo brings a sense of stability and predictability, but it can lead stigmatized individuals to downplay their experience of discrimination. For example, in one experiment White and Latino students were put in the same situation of feeling that they had been passed over for a job that was given to someone of another ethnicity (Major et al., 2002). To what extent did they view this as discrimination? The results were quite different, depending on the students’ ethnicity. Among Whites, those most convinced that the social system in America is fair, and that hard work pays off, thought it was quite discriminatory for a Latino employer to pass them over to hire another Latino. After all, if the system is fair, and Whites have been very successful in the system, an employer has no justification for choosing a minority-

APPLICATION: Is Perceiving Prejudice Bad for Your Health?

|

APPLICATION: |

| Is Perceiving Prejudice Bad for Your Health? |

Living in a society that devalues you because of your ethnicity, your sexual preferences, or religious attitudes can take a toll on both your mental and your physical health. Several studies have shown that people who report experiencing more prejudice in their daily lives also show evidence of poorer psychological health (Branscombe et al., 1999; Schmitt et al., 2014). Negative consequences, such as increased depression and lower life satisfaction, are especially extreme when people blame themselves for their stigma or the way people treat them.

American sports leagues still have team names such as the Cleveland Indians and the Washington Redskins, with mascots to match. If the same type of ethnic mascots existed for other groups, would we more easily recognize them as being offensive?

[AUTH © 1997 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.]

392

Because our culture is infused with stereotypic portrayals of various groups, these negative effects on mental health can be quite insidious. For example, there is an ongoing national debate about the use of Native American images as mascots for school and sports teams. Do these images honor the proud history of a cultural group? Or do they present an overly simplistic caricature that debases a segment of society? Research shows that when Native American children and young adults are primed with these images, their self-

Prejudice can have long-

Although perceiving frequent discrimination predicts poorer well-

The Harmful Impact of Stereotypes on Behavior

Teachers’ expectations of students’ abilities can subtly shape their interactions with those students in ways that confirm their stereotypes.

[nano/ESTX/Getty Images]

Although being the target of prejudice has the power to affect how people perceive themselves, it also can affect how they behave and perform. When you hold a stereotypic expectation about another person (because of their group membership, for example) you may act in a way that leads the stereotyped person to behave just as you expected. For example, you suspect that the clerk at the café is going to be rude, so you are curt with her. She responds by being curt back to you and Voilà! Your initial judgment seems to be confirmed. Yet you may be ignoring the fact that, had you approached the interaction with a different expectation in mind, she might not have acted rudely.

This was demonstrated in a classic study by Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) in which teachers’ stereotypic expectations of their students actually changed how those students performed in school. Students who were identified to the teachers as “bloomers”—that is, those who would likely experience a spurt in intellectual development—

393

The Rosenthal and Jacobson study demonstrates the power of positive expectations in creating self-

The answer is yes. In a second study, the researchers trained their assistants to conduct an interview either using the “good interviewer” style that was more typical of the interviews with White candidates (e.g., sitting closer) or the “bad interviewer” style that was more typical of the interviews with Black candidates (e.g., sitting farther away). When the trained assistants interviewed unsuspecting White job candidates, an interesting pattern emerged. Those job candidates assigned to a “bad” interviewer came across as less calm and composed than those assigned to the “good” interviewer.

More recent research shows just how subtle these effects can be. In one set of studies, when female engineering students were paired with a male peer to work together on a project, his implicit sexist attitudes about women predicted her poorer performance on an engineering test (Logel et al., 2009). An interesting difference in this case was that the stereotype-

Confirming Stereotypes to Get Along

Such findings point to a powerful dilemma. Stereotypes are schemas. If you return to the function of schemas we discussed in chapter 3, you’ll remember that they help social interactions run smoothly. People get along better with each other when both individuals confirm the other person’s expectations. This suggests that the more motivated people are to affiliate and interact positively with someone, the more likely they will be to behave in ways that are consistent with the other person’s stereotypes, a form of self-

394

FIGURE 11.1

Conforming to Stereotypes

Women who were motivated to get along with others (high in affiliative motivation) acted more stereotypically during a conversation with a man the more they believed that he had sexist views about women.

[Data source: Sinclair et al. (2005)]

This is exactly what research shows. In one study (Sinclair et al., 2005), women had a casual conversation with a male student whom they were led to believe had sexist or nonsexist attitudes toward women. In actuality, he was a member of the research team trained to act in a similar way with each woman and to rate his perceptions of her afterward. Those women who generally had a desire to get along with others and make new friends (i.e., they were high in affiliative motivation) rated themselves in more gender-

Objectification

Although many consequences of being stigmatized apply broadly to different forms of prejudice, some are more specific to particular identities. One important example is the objectification that can result from the strong focus in many cultures on women’s bodies. The art historian John Berger (1972) wrote, “A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. She has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life” (p. 46).

In chapter 10, we discussed how the sexual objectification of women promotes certain stereotypes and prejudice against them. But Fredrickson and Robert’s (1997) objectification theory also proposes that this intense cultural scrutiny of the female body leads many girls and women to view themselves as objects to be looked at and judged, a phenomenon that the researchers called self-

Self-objectification

A phenomenon whereby intense cultural scrutiny of the female body leads many girls and women to view themselves as objects to be looked at and judged.

Self-

395

Women who are particularly susceptible to such self-

Stereotype Threat

Self-

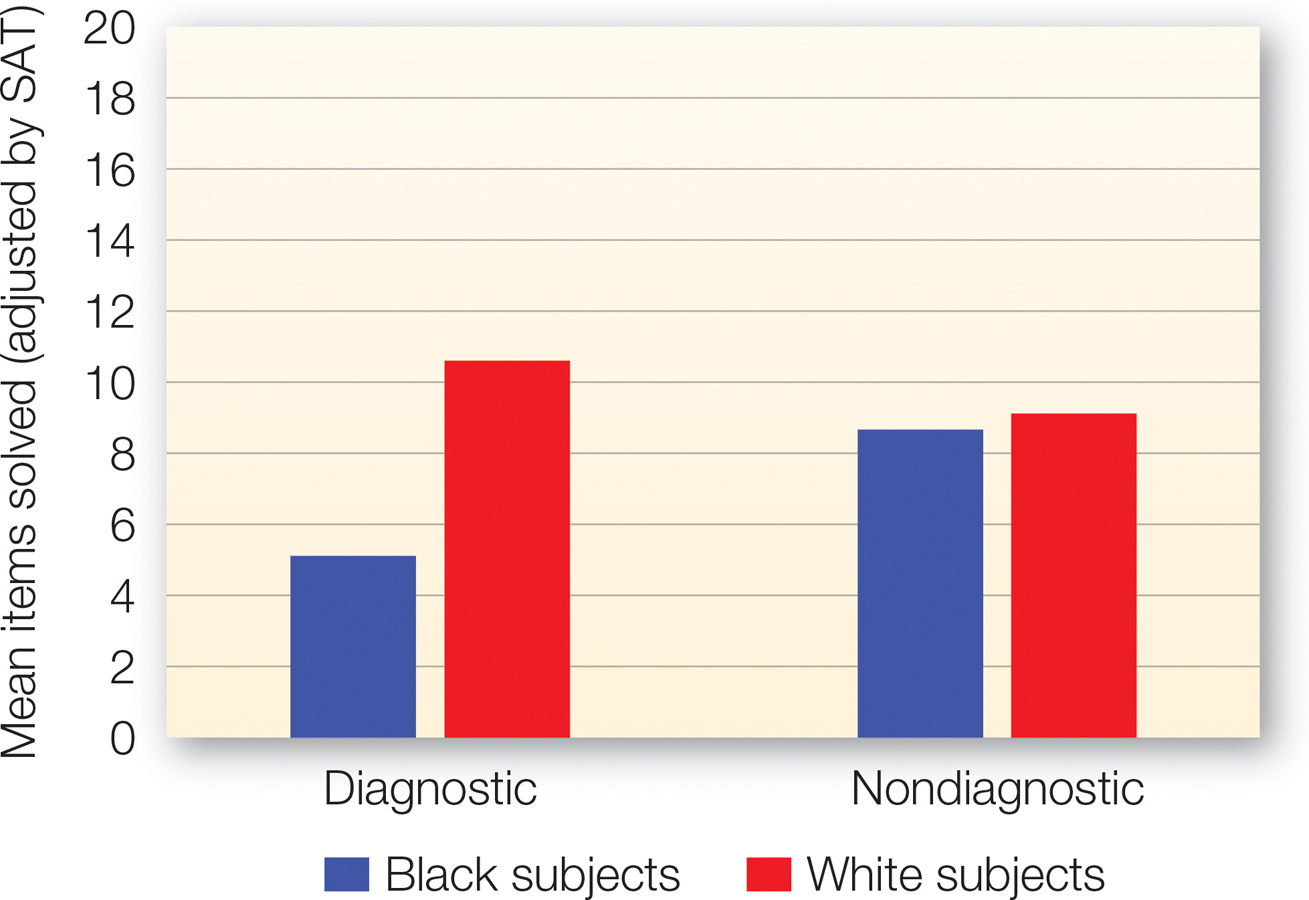

FIGURE 11.2

Stereotype Threat

In research on stereotype threat, Black college students performed significantly worse when a task was framed as a diagnostic test of verbal ability rather than as a nondiagnostic laboratory exercise.

[Data source: Steele & Aronson (1995)]

Stereotype threat is the concern that one might do something to confirm a negative stereotype about one’s group either in one’s own eyes or the eyes of someone else. Although this phenomenon has far-

Stereotype threat

The concern that one might do something to confirm a negative stereotype about one’s group either in one’s own eyes or the eyes of someone else.

In addition to undermining performance on tests of math, verbal, or general intellectual ability of minorities, women, and those of lower socioeconomic status (Croizet & Claire, 1998), stereotype threat has also been shown to impair memory performance of older adults (Chasteen et al., 2005); driving performance of women (Yeung & von Hippel, 2008); athletes’ performance in the face of racial stereotypes (Stone et al., 2012); men’s performance on an emotional sensitivity task (Leyens et al., 2000); and women’s negotiation skills (Kray et al., 2001).

396

Stereotype threat is more likely to impair performance under some conditions than others (Schmader et al., 2008). The effect is strongest when:

the stigmatized identity is made salient in the situation (e.g., being the only women in a high-

that identity is chronically salient, due to high stigma consciousness or high identification with the group.

the task is characterized as a diagnostic measure of an ability for which one’s group is stereotyped as being inferior (as in Steele & Aronson, 1995).

individuals are led to believe their performance is going to be compared with that of members of the group stereotyped as superior on the task.

individuals are explicitly reminded of the stereotype.

Researchers also have learned a great deal about the processes that contribute to the deleterious effects of stereotype threat. First, it’s important to point out that those who care the most about being successful feel stereotype threat most acutely (Steele, 1997). You have to be invested in doing well to be threatened by the possibility that you might not. In fact, it’s partly because people are trying so hard to prove the stereotype wrong that their performance suffers (Jamieson & Harkins, 2007). When situations bring these stereotypes to mind, anxious thoughts and feelings of self-

Just as some people see their performance suffer in the face of negative stereotypes, others can get a boost in performance from reminders that they are positively stereotyped (Rydell et al., 2009; Shih et al., 2002; Walton & Cohen, 2003), a phenomenon known as stereotype lift. One caveat, however, is that when these positive stereotypes are communicated directly and explicitly (“Oh, you should do well on this math test because you’re Asian”), people can also choke under the pressure of having to live up to such high expectations (Cheryan & Bodenhausen, 2000; Shih et al., 2002).

Social Identity Threat

Research on stereotype threat reveals that it’s mentally taxing to cope with situations that communicate to you that you are incompetent. A more general version of this threat is called social identity threat, the feeling that your group simply is not valued in a domain and that you do not belong there (Steele et al., 2002). As a result, those who try to enter and excel in areas where their group has traditionally been underrepresented find themselves trying to juggle their various identities. For example, women who go into male-

On the one hand, repeated exposure to stereotype threat and social identity threat can eventually lead to disidentification, which occurs when people no longer feel that their performance in a domain is an important part of themselves, and they stop caring about being successful (Steele, 1997). This can be a serious problem if, for example, minority children disidentify with school. In fact, being the target of negative stereotypes can steer people away from certain opportunities in the first place.

Disidentification

The process of disinvesting in any area in which one’s group traditionally has been underrepresented or negatively stereotyped.

Women sitting at the computer scientist’s desk on the left (with the Star Trek poster) expressed less interest in computer science as a major than did women sitting at the computer scientist’s desk on the right. The geek stereotype of computer scientists might prevent women from becoming interested in this field.

[Cheryan et al. (2010)]

397

For example, although women continue to be underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and math compared with men, FIGURE 10.4 (PhDs Earned by Women) in the previous chapter revealed that their numbers have been steadily increasing over time. In the one exception to this trend, the number of women entering computer science has actually been decreasing over the past two decades. Research suggests why this might be: Students have a very specific stereotype of what a computer scientist is like, and women are much more likely than men to think that it isn’t like them. In one study, women expressed far less interest in majoring in computer science when they completed a survey in a computer scientist’s office filled with reminders of the computer-

What’s a Target to Do? Coping With Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Given the severity of consequences associated with the existence of cultural stereotypes as well as perceiving and being the victim of prejudice, how should a targeted individual respond? People react in quite a number of ways. Some are specifically focused on protecting oneself from stereotype threat. Others focus on ameliorating other negative consequences of prejudice. Interestingly, one review of the literature revealed surprisingly little evidence that people stigmatized based on race, ethnicity, physical disability, or mental illness report lower levels of self-

So how do people who are devalued by society in general minimize these hits to self-

Combating Stereotype and Social Identity Threat

We’ve reviewed the powerful role that prejudice and negative stereotypes can play in shaping behavior, self-

398

Identification with Role Models

One set of strategies is aimed at changing or reducing the stereotype itself. When individuals are exposed to role models—

Reappraisal of Anxiety

When stereotypes are difficult to change, targets can reinterpret what the stereotypes mean. For example, often, when people think that they are stereotyped to do poorly, they are more likely to interpret difficulties and setbacks as evidence that the stereotype is true and that they do not belong. They perform better, though, if they reinterpret difficulties and setbacks as normal challenges faced by anyone. In one remarkable study, minority college students who read testimonials about how everyone struggles and feels anxious when beginning college felt a greater sense of belonging in academics, did better academically, and were less likely to drop out of school (Walton & Cohen, 2007, 2011). Similarly, instructions to reappraise anxiety as a normal part of test-

Self-affirmation

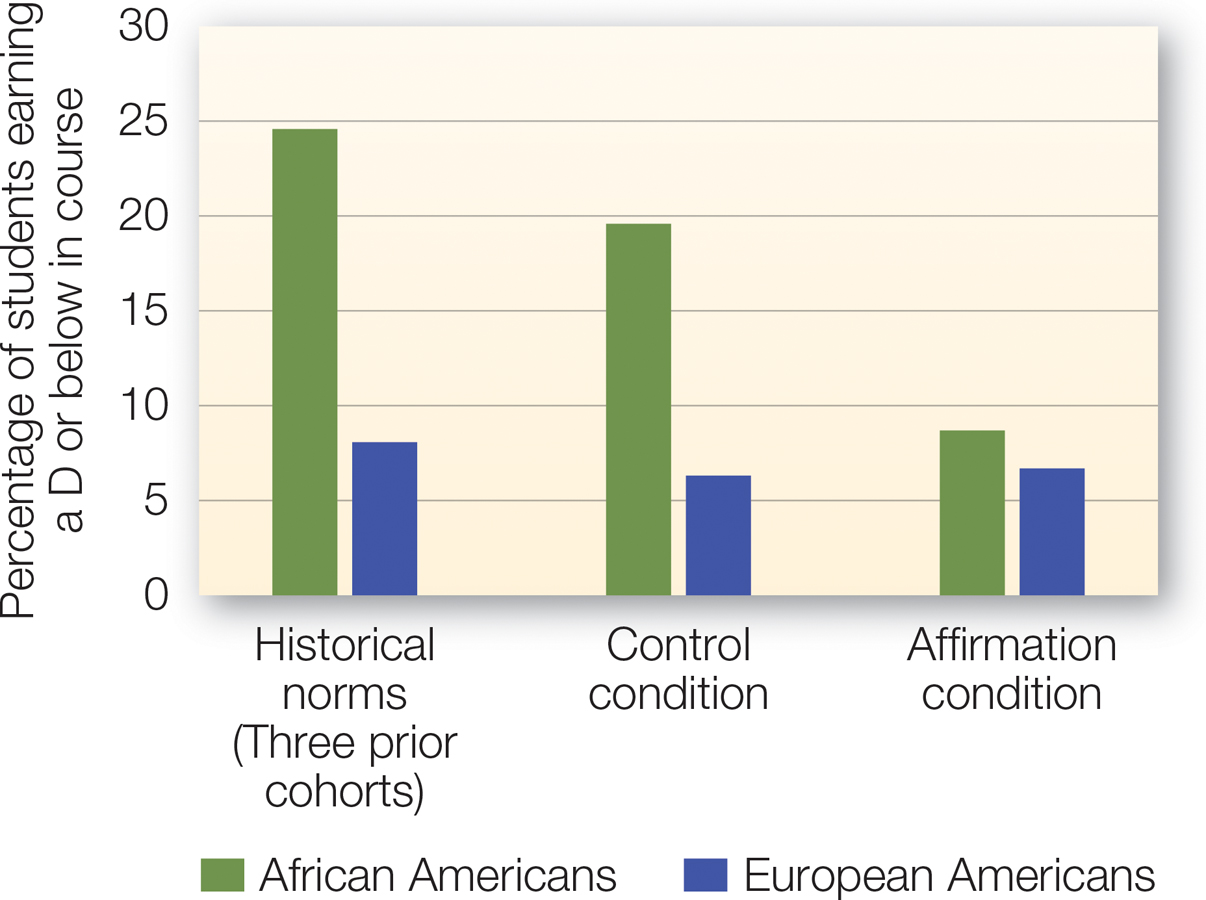

FIGURE 11.3

The Power of Self-

When middle school students spent just 15 minutes at the start of the school year reflecting on their core values, the percentage of African American students who earned a D or lower at the end of the semester was dramatically reduced.

[Data source: Cohen et al. (2006)]

Another remarkably successful coping strategy is self-

Social Strategies for Coping With Prejudice and Discrimination

Just as there are a number of ways to counter the effects of stereotype threat, there are also a number of behavioral response options for dealing with interpersonal encounters with prejudice.

399

Confrontation

Wanting to experience positive outcomes and to believe in fairness can make someone less likely to perceive discrimination. But even when people feel they have been the targets of biased attitudes or perceptions, they don’t always say that discrimination has occurred or do anything to confront the person responsible.

Consider the following scenario: You are working on a class project in small groups, and you have to take turns choosing what kinds of people you would want with you on a deserted island. One young man in the group consistently makes sexist choices. (“Let’s see, maybe a chef? No, one of the women can cook.”) Would you say anything to him? In a study that presented women with this scenario, most said they would confront the guy in some way, probably by questioning his choice or pointing out how inappropriate it is (Swim & Hyers, 1999). But when women were actually put in this situation, over half of them did nothing at all.

This “do-

…”Fools”, said I, “You do not know

Silence like a cancer grows

Hear my words that I might teach you

Take my arms that I might reach you”

But my words, like silent raindrops fell

And echoed

In the wells of silence

—Simon & Garfunkel

Why do racist and sexist remarks often go unchallenged? One reason is because those who do the confronting are often viewed negatively. When participants hear about a Black student who claims that his failing grade was the result of racial discrimination, they see him as a complainer (Kaiser & Miller, 2001). This kind of “blame the victim” reaction happens even when the evidence supports the student’s claim that discrimination actually occurred! In other research, when Whites were confronted with the possibility that they might be biased in their treatment of others, they did try to correct their biases in the future, but they also felt angry and tended to dislike the person who confronted them (Czopp et al., 2006). Even members of your own stigmatized group can be unsympathetic when you point to the role of discrimination in your outcomes (Garcia et al., 2005). These social costs can make it difficult to address bias when it does occur, particularly if you are the person targeted by the bias and in a position of relatively little power.

Despite the costs of confrontation, real social change requires it. This raises the question, are other options available that might get a similar message across but in a way that minimizes these costs? According to the target empowerment model, the answer is yes (Stone et al., 2011). This model suggests that targets of bias can employ strategies that deflect discrimination, so long as those actions aren’t perceived as confrontational. And even those that are confrontational can still be effective if they are preceded by a strategy designed to put a prejudiced person at ease.

Target empowerment model

A model suggesting that targets of bias can employ strategies that deflect discrimination, as long as those methods aren’t perceived as confrontational.

Let’s illustrate how this model works. In post–

400

Think ABOUT

When have you confronted someone who was biased against you or another person? What was the cost?

Compensation

To ease interracial tension, minority students self-

[Christine Glade/ESTX/Getty Images]

Targets of prejudice also can cope with stigma by compensating for the negative stereotypes or attitudes they think other people have toward them. For example, when overweight women were making a first impression on a person and were led to believe that that person could see them (and thus knew their weight), they acted in a more extraverted way than if they were told that they could not be seen. They compensated for the weight-

In a similar finding, Black college freshmen who expected others to have racial biases against them and their group reported spending more time disclosing information about themselves when talking with their White dormitory roommates (Shelton et al., 2005). Self-

Unfortunately, these kinds of compensation strategies can come with costs. In the study just mentioned, the Black participants who reported engaging in a lot of self-

Another potential cost of compensation is that it can disrupt the smooth flow of social interaction. This is because the specific concerns that weigh on the mind of the target, and thus trigger their compensation, might be quite different than what weighs on the mind of the perceiver (Bergsieker et al., 2010; Shelton & Richeson, 2006). For people who belong to the more advantaged group, interactions with outgroup members can bring to mind concerns about appearing prejudiced (Vorauer et al., 1998). Assuming that they would prefer that they and their group were not seen as prejudiced jerks, we might expect them to be motivated to ingratiate themselves with others in order to come across as likeable. Thus, they will likely try to come across as warm and open, while also being careful to not let any biases pervade their judgment.

For people who belong to the disadvantaged group, the concerns for the interaction can be quite different. If you take the often-

401

APPLICATION: The Costs of Concealing

|

APPLICATION: |

| The Costs of Concealing |

When Jason Collins joined the Brooklyn Nets in the spring of 2014, he became a true trailblazer—

[NBAE/Getty Images]

When people are concerned about being discriminated against, it is not surprising that they might sometimes choose to cope by concealing their stigma, if this is an option. This strategy is common in the case of sexual orientation, which, unlike race or gender, is easily concealed. For example, Jason Collins played professional basketball in the NBA for 12 years before coming out of the closet in April 2013. In his interview with Sports Illustrated, he described his experience concealing his sexual orientation:

No one wants to live in fear. I’ve always been scared of saying the wrong thing. I don’t sleep well. I never have. But each time I tell another person, I feel stronger and sleep a little more soundly. It takes an enormous amount of energy to guard such a big secret. I’ve endured years of misery and gone to enormous lengths to live a lie. I was certain that my world would fall apart if anyone knew. And yet when I acknowledged my sexuality I felt whole for the first time (COLLINS & LIDZ, 2013).

When Jason Collins joined the Brooklyn Nets in the spring of 2014, he became a true trailblazer—

In some circumstances and for some people, concealment can be beneficial. In a study of HIV-

But as Jason Collins’s quote reveals, concealment comes with its own costs. Like the African American college students who feel inauthentic in the way they find themselves self-

Being involuntarily “outed” brings an additional cost: the emotional and social consequences of having one’s stigmatized identity revealed to the world. A gay 18-

The It Gets Better Project is a campaign to provide gay and lesbian youth with positive role models of gay and lesbian adults who live happy and successful lives, even if they, too, experienced discrimination as adolescents.

[It Gets Better Project]

402

Tyler Clementi’s suicide is part of a larger epidemic: Gay, lesbian, and bisexual teens are three times more likely to attempt suicide than their straight peers (Meyer, 2003), but these rates decrease as teens move into young adulthood (Russell & Toomey, 2012). Because stigma is a threat to one’s very sense of identity, it might not be a coincidence that the negative consequences of prejudice are particularly high during adolescence and young adulthood, when people are still forming an identity (Erikson, 1968). The It Gets Better project (www.itgetsbetter.org), started by the columnist and author Dan Savage and his partner, Terry Miller, is an effort to communicate to LGBT teens that the stress of embracing their sexual identity, coming out to others, and experiencing bias will get better for them as they mature.

The Benefits of Group Identification

At the other end of the spectrum from concealment is creating and celebrating a shared identity with others who are similarly stigmatized. It’s long been known that people benefit in extraordinary ways from receiving social support from others. Such support can be most helpful when it comes from someone who has “been there” and has gone through the same experience. Earlier we mentioned that those who report encountering frequent or ongoing discrimination show signs of psychological distress. But according to rejection identification theory, the negative consequences of being targeted by discrimination can be offset by a strong sense of identification with your stigmatized group (Branscombe et al., 1999; Postmes & Branscombe, 2002).

Rejection identification theory

The idea that people can offset the negative consequences of being targeted by discrimination by feeling a strong sense of identification with their stigmatized group.

The old adage that there is safety in numbers applies not only to physical protection but to a less tangible sense of symbolic protection as well. Although pride in one’s ethnic identity is likely supported by one’s family and social circle, often such support is less readily available for those with stigmatizing identities such as homosexuality, physical deformity, and obesity. In such cases, even parents, siblings, and friends may reject the stigmatizing identity. That is why gay pride and similar movements can be so critical to a feeling of social support.

Modern travel and communication makes it easier for those who are stigmatized to find and connect with others with similar experiences. Bao Xishun (7′9″) and He Pingping (2′4″), met in 2007 when they were the world’s tallest and shortest men.

[Chinatopix/Associated Press]

If there are psychological benefits of banding with similar others to cope with prejudice, it is easier to understand why people often self-

Psychological Strategies for Coping With Prejudice and Discrimination

The social strategies discussed above offer examples of how those who are stigmatized can manage their interpersonal interactions in ways that minimize their experience of bias and discrimination. Because people experience discrimination and bias in society at large as well as in interpersonal interactions, a host of psychological strategies are directed toward helping people remain resilient in the face of social devaluation.

403

Discounting

As we mentioned earlier, the dilemma of modern-

Attributional ambiguity

A phenomenon whereby members of stigmatized groups often can be uncertain whether negative experiences are based on their own actions and abilities or are the result of prejudice.

Being socially stigmatized means that you often experience attributional ambiguity when it isn’t clear if others treat you badly because of their prejudices or because of something you actually did.

[Getty Images/iStockphoto]

You might be wondering how perceiving discrimination can sometimes be psychologically beneficial after we outlined all of its negative consequences. First, attributing an isolated incident to prejudice might buffer self-

People can also protect their self-

Devaluing

Another coping strategy that people turn to in dealing with discrimination is to devalue those areas of life where they face pervasive experiences of prejudice and discrimination. If you decide that you really don’t care about working on a naval submarine, then you might be relatively unaffected by the U.S. Navy’s long-

When people fail, fear rejection, or are excluded from a domain or type of activity, they can quite easily devalue that domain. This might be part of the reason that women are less likely to pursue advanced degrees in science and engineering. The tendency to devalue those areas where your group doesn’t excel seems like a pretty effective strategy for managing bad outcomes. But the whole story is more complicated. It turns out that it is not so easy to devalue those domains in which higher-

404

These pressures can leave people with a difficult choice: Continue to strive for success in arenas where they are socially stigmatized because these are the domains that society considers important or call into question the very legitimacy of that society by devaluing those domains (e.g., making the decision to drop out of school). For example, although Black and Latino college students get lower grades on average than their White and Asian peers, they report valuing education at least as much if not more (Major & Schmader, 1998; Schmader et al., 2001). However, those who regard the ethnic hierarchy in the United States as unfair and illegitimate are more likely to call into question the value and utility of getting an education (Schmader et al., 2001). If the deck is stacked against you, you might very well decide to leave the game.

Devaluing one area of life may help mitigate a setback in that area. How do groups cope with the perception that persistent discrimination creates multiple, insurmountable barriers to their success, from inferior schooling to glass-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

One Family’s Experience of Religious Prejudice

One Family’s Experience of Religious Prejudice

In this chapter, we are considering the scholarly evidence on how people experience, cope with, and try to deflect discrimination. But for those who are targeted by social biases, personal experience with prejudice can cut very deep. Let’s examine prejudice from the perspective of one family’s account told as part of the radio program This American Life (Spiegel, 2006, 2011).

We begin with a love story in the West Bank in the Middle East. A young Muslim American woman named Serry met and fell in love with a Muslim man from the West Bank. As they got to know one another, he told her how difficult it was for him and everyone he knew to grow up in the middle of the deep religious and political conflict between Israel and the West Bank. So when they decided to marry and make a life together, she convinced him that their children would have a better life in the United States, a country where she spent a much happier childhood and where people from different religious backgrounds easily formed friendships.

They settled down in the suburbs of New York City, had five children, and became a very typical American family. But when terrorists attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, their lives changed forever. Like everyone around them, they were horrified and deeply saddened by what had happened. But their friends, neighbors, and even strangers on the street began to treat them differently. Drivers would give Serry the finger, and someone put a note on her minivan telling her family to leave the country. The situation escalated when their fourth-

This heart-

The oldest daughter’s response was to renounce her religion, to try to escape that part of her identity that her peers and her teacher so clearly devalued. When she moved to a new school, she chose to conceal her religious background to try to avoid further discrimination.

For Serry, the mother of the family, her religion was deeply important to her but being American was even more central to her identity. She was shocked and saddened to find that she was no longer viewed as an American, but she still believed that American values of freedom would win out in the end. As Serry explained, “I was born and raised in this country, and I’m aware of what makes this country great, and I know that what happened to our family, it doesn’t speak to American values. And I feel like this is such a fluke. I have to believe this is not what America is about. I know that.” In line with system justification theory, her belief in American values led her to minimize these events as aberrations.

But for Serry’s husband, his vision of America as a land free of religious prejudice was shattered. Like every immigrant before him in the history of the United States, he had traveled to a new and different culture in the hope of making a better life for himself and his family. Once a very happy man with a quick sense of humor, he slipped into depression and eventually decided to return to the West Bank, where he died a few years later. Not much is said about his death, so it’s not known how his experience with anti-

405

|

Prejudice From a Target’s Perspective |

|

The effects of prejudice can weigh heavily on its targets, but people can take steps to mitigate its consequences. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Perceiving prejudice Because modern prejudice is less overt, it is difficult to know if and when one is the target of prejudice. People differ in their sensitivity to prejudice, but people commonly underestimate personal discrimination. People may be motivated to deny discrimination out of optimism or a desire to justify the social system. Prejudice can take a toll on a person’s mental and physical health. |

The harmful impact of stereotypes Holding a stereotype can change how observers interact with targets, sometimes causing targets to act stereotypically. Targets sometimes inadvertently act stereotypically to get along with others. Self- Stereotype threat— Social identity threat— |

Coping with prejudice Ways to overcome stereotype threat include: identifying with role models, reappraising anxiety as normal, and self- To address or minimize their experience of prejudice in social interactions, stigmatized targets use confrontation, compensation, concealment, and coming together. To minimize the negative psychological effects of social devaluation, stigmatized targets can discount negative outcomes or devalue domains where they experience discrimination. These strategies can benefit targets in some situations, but they can also backfire or create new problems. |

406