6.1 The Motive to Maintain a Consistent Self

People want to perceive consistency among the specific things they believe, say, and do—

190

Self-consistency at the Micro Level: Cognitive Dissonance Theory

According to Leon Festinger’s (1957) cognitive dissonance theory, people have such distaste for perceiving inconsistencies in their beliefs, attitudes, and behavior that they will bias their own attitudes and beliefs to try to deny those inconsistencies. The basic idea is that when two cognitions (e.g., beliefs, attitudes, or perceived actions) are inconsistent or contradict one another, people experience an uncomfortable psychological tension known as dissonance. The more important the inconsistent cognitions are to the person, the more intense the feeling of dissonance and the stronger the motivation to get rid of that feeling. There are three primary ways to reduce dissonance:

Cognitive dissonance theory

The idea that people have such distaste for perceiving inconsistencies in their beliefs, attitudes, and behavior that they will bias their own attitudes and beliefs to try to deny inconsistencies.

Change one of the cognitions.

Add a third cognition that makes the original two cognitions seem less inconsistent with each other.

Trivialize the cognitions that are inconsistent.

FIGURE 6.1

Smoking and Dissonance

Smokers often are experts at generating additional cognitions to reduce the dissonance created by doing something they know is bad for their health. How many of these have you heard before, or used yourself if you’re a smoker?

Let’s consider, as Festinger did back in the 1950s, the example of a cigarette smoker. Sally the smoker has two cognitions: (1) she knows cigarettes are bad for her health; and (2) she knows that she smokes cigarettes. From the cognition “Smoking is bad for me” follows the opposite cognition “I smoke.” As a result, Sally often feels tense and conflicted about her smoking—

Think ABOUT

When it’s hard to change either of the dissonant cognitions, people usually add a third cognition that resolves the inconsistency between the original two cognitions. Take a minute to think of any additional cognitions that smokers use to try to reduce their dissonance. Now review the list in FIGURE 6.1. How many of these rationalizations did you come up with? These added cognitions help to reduce dissonance, but they also make it easier to avoid the difficult but healthy change of quitting.

A third way to reduce dissonance is to trivialize one of the inconsistent cognitions (Simon et al., 1995). Let’s illustrate this with an example. Suppose you buy a plasma TV, knowing that they use more energy than LED TVs. If you were to reduce dissonance by trivializing one of the cognitions, you could think to yourself, “With all the energy use in the United States, the extra electricity my new TV will use is a tiny drop in the bucket.”

191

To understand more about the conditions that arouse dissonance and the ways people reduce it, researchers have come up with a number of laboratory situations, or dissonance paradigms. Two such situations are the free choice paradigm and the induced compliance paradigm.

The Free Choice Paradigm

The free choice paradigm (Brehm, 1956) is based on the idea that any time people make a choice between two alternatives, there is likely to be some dissonance. This is because all of the bad aspects of the alternative people chose, and all of the good aspects of the alternative they rejected, are inconsistent with their choice. The harder the choice, the more of these inconsistent elements there will be, and so the more dissonance there will be after the choice is made.

Free choice paradigm

A laboratory situation in which people make a choice between two alternatives, and after they do, attraction to the alternatives is assessed.

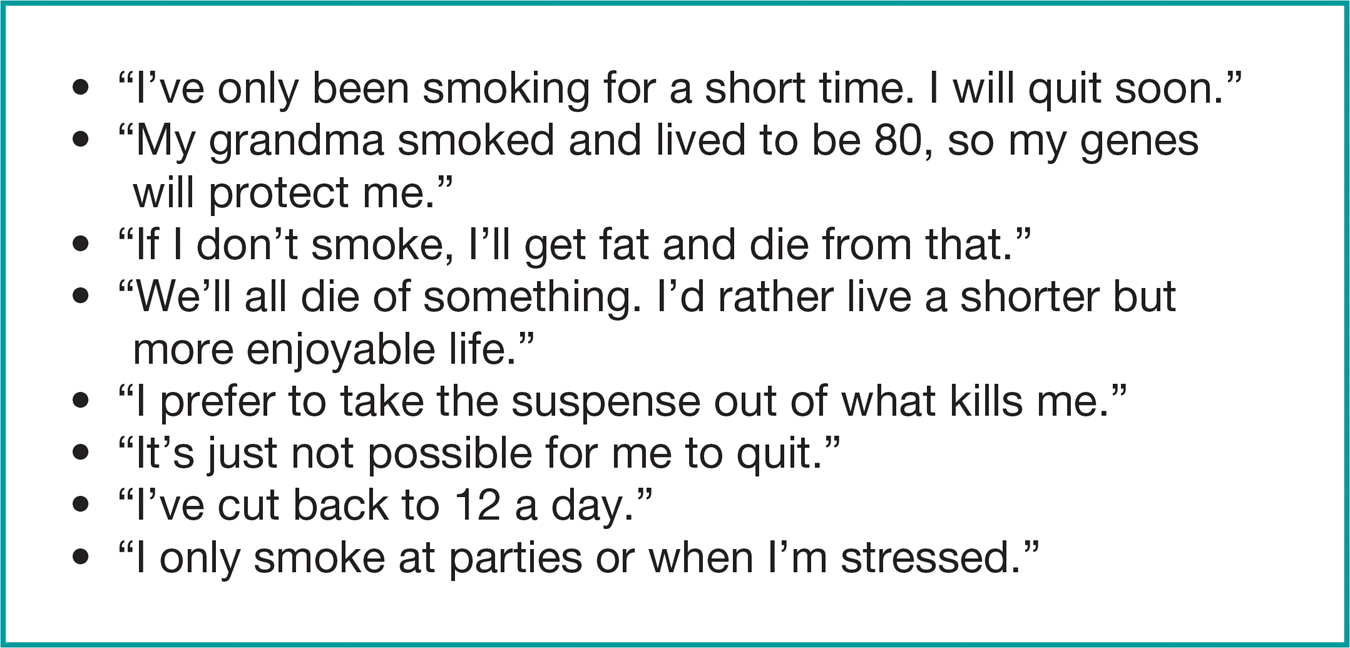

FIGURE 6.2

Brehm’s Free Choice Paradigm

In the free choice paradigm (Brehm, 1956), participants in the high dissonance condition are asked to make a difficult choice between two similarly attractive options. Participants in the low dissonance condition make an easy choice between one attractive and one unattractive option. After making their choices, participants in the high dissonance condition increase their liking for what they chose and decrease their liking for what they didn’t choose, a spreading of alternatives.

[Research from Brehm (1956)]

How do people cope with this dissonance? They do so by spreading the alternatives: After the choice is made, people generally place more emphasis on the positive characteristics of the chosen alternative and the negative aspects of the rejected alternative. For example, if you chose a fuel-

To test this idea, Brehm (1956) asked one group of participants to choose between two consumer items (e.g., a stop watch, a portable radio) that they liked a lot (FIGURE 6.2). This was a difficult decision. The other group was asked to choose between an item they liked a lot and one that they didn’t like, which is an easy decision. After participants chose the item they wanted, they were again asked to rate how much they liked them. Brehm reasoned that when the choice was easy, participants would not feel much dissonance, and so they would rate the items pretty much as they had before their decision. But the participants who made a difficult decision would feel dissonance because their cognition “I made the right choice” is inconsistent with their cognition “The item I chose has some negative aspects, and the one I didn’t choose has some attractive aspects.” Brehm expected these participants to spread the alternatives on their second rating, exaggerating their chosen item’s attractiveness and downplaying the other item’s value. This is exactly what he found. Related research shows that people also spread the alternatives following a difficult choice by searching for information that supports their choice and avoiding information that calls their choice into question (e.g., Frey, 1982).

The Induced Compliance Paradigm

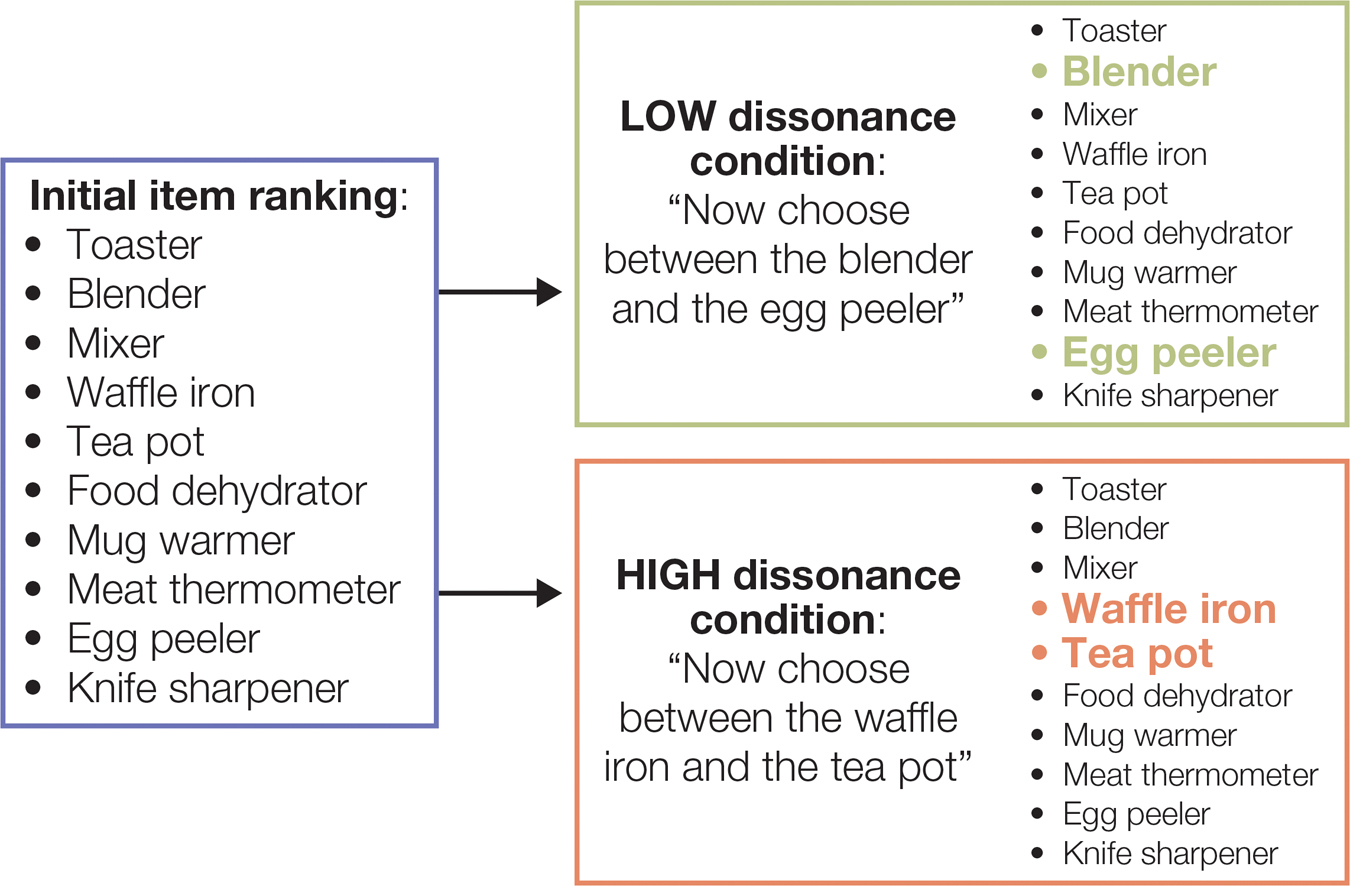

FIGURE 6.3

Support for Dissonance Theory Using the Induced Compliance Paradigm

When participants told another person that they liked a boring task, those who received $1.00 later reported liking the task more than those who received $20.00 and those who did not say they liked the task. Lacking sufficient justification for lying, participants in the $1.00 condition reduced dissonance by bringing their attitude in line with their behavior.

[Data source: Festinger © Carlsmith (1959)]

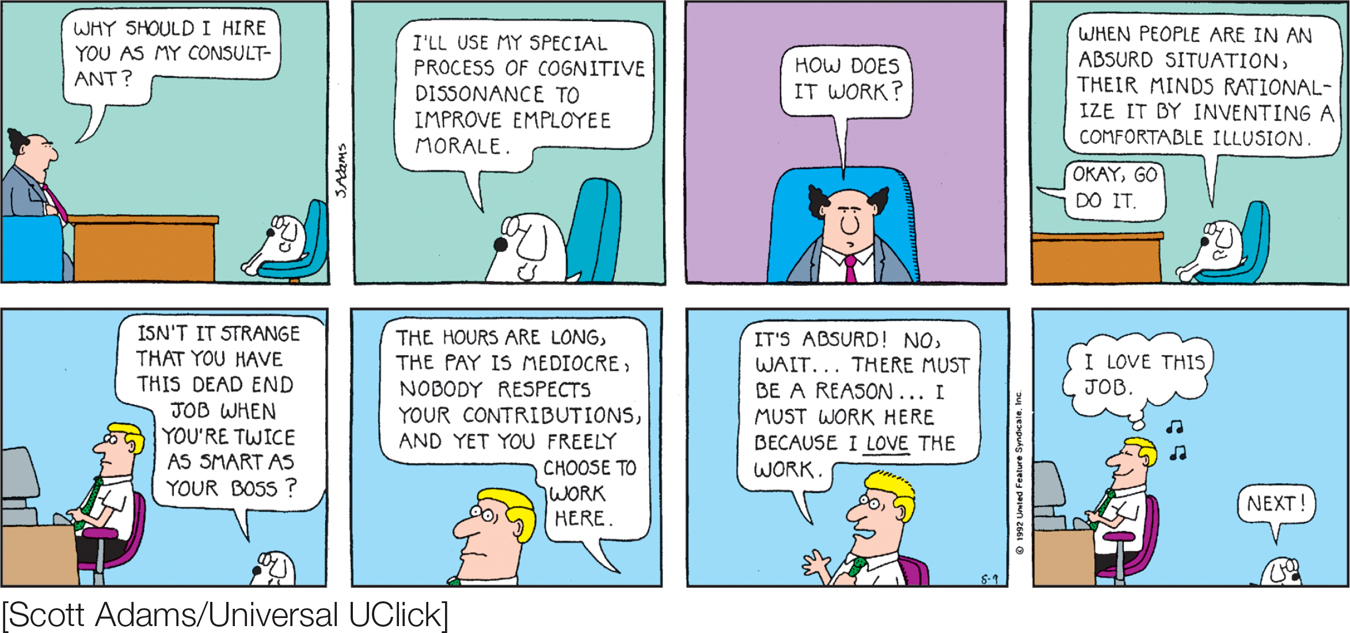

Dissonance is aroused whenever people make difficult choices. And many of our difficult choices result from our being pulled in opposite directions, as when we’re induced to say something we don’t truly believe. For example, when your professor asks you whether you liked today’s sleep-

192

The situation that Festinger and Carlsmith created to arouse dissonance in the lab has become known as the induced compliance paradigm. This is because the participants are induced to comply with a request to engage in a behavior that runs counter to their true attitudes.

Induced compliance paradigm

A laboratory situation in which participants are induced to engage in a behavior that runs counter to their true attitudes.

Factors That Affect the Magnitude of Dissonance

Will people always experience dissonance when their behavior is inconsistent? Festinger argued that virtually any action a person engages in will be inconsistent with some cognition the person holds, but he did not think actions will always lead to strong feelings of dissonance. Much of the time people think or act in inconsistent ways without even being aware that they’re doing so. Research shows that people feel dissonance primarily when the inconsistent cognitions are salient or highly accessible to consciousness (Newby-

Weak External Justification

Dissonance will be high if you act in a way that is counter to your attitudes with only weak external justification to do so. On the other hand, if the external justification is very strong, dissonance will be low. As we saw in the Festinger and Carlsmith study, $1.00 was a weak justification, so participants changed their attitude to reduce dissonance; $20.00 was a strong external justification, so participants maintained their original attitude. External justification doesn’t have to come in the form of money; it can also be praise, grades, a promotion, or pressure from loved ones or authority figures. All of these can provide added cognitions that reduce overall dissonance.

Choice

As the work on the free choice paradigm might suggest, a key factor in creating dissonance in the induced compliance paradigm is perceived choice (Brehm & Cohen, 1962). Just as $20.00 is an added cognition that reduces the overall dissonance, so too is a lack of choice. If some twisted character held a gun to your head and told you to say your mom is an evil person, you’d probably do it and not feel too much dissonance about it. But neither would you feel you had much choice in the matter, because although the statement would be inconsistent with your love for your mom, it is quite consistent with wanting to stay alive. To study the role of perceived choice, Brehm and Cohen (1962) developed what has become the most common method for creating dissonance through induced compliance. It involves asking participants to write a counterattitudinal essay, that is, an essay that is inconsistent with their beliefs. One study using this method (Linder et al., 1967) showed that when an experimenter simply ordered students to write an essay in favor of an unpopular position—

193

Commitment

When people’s freely chosen behavior conflicts with their attitudes, the more committed they are to the action, the more dissonance they experience. If the action can be taken back or changed easily, that reduces the extent to which the action is dissonant with one’s attitude. After all, if you can just take it back, why change your attitude? A study by Davis and Jones (1960) illustrates this point. They induced participants to help the experimenter by insulting another person, and either gave participants a sense of choice in doing so (high choice condition) or did not (low choice condition). In addition, half of the participants thought they would be able to talk to the person later and explain that they didn’t really mean what they said and were just helping the experimenter (low commitment—

If you’re having a rough day and happen to treat someone badly and can’t take it back, you might reduce your dissonance by deciding the person deserves the insult. And this is just what happened in the high choice, high commitment condition: The participants rated the person they insulted negatively. This did not occur in the low choice condition, and it also didn’t occur in the high choice condition if the insult could be taken back. A clever field experiment at the track by Knox and Inkster (1968) also supported the role of commitment. They showed that horse-

Foreseeable Aversive Consequences

The more aversive the foreseeable consequences of an action are, the more important the inconsistent cognitions are, and thus, the more dissonance. Imagine you wrote an essay arguing that smoking cigarettes is a good thing to do (it’s a legal way to get a buzz, it makes you look cool) and either: (a) threw it away; or (b) read it to your 10-

Cultural Influences

Although a consistent sense of self is an important aspect of being human, different situations may arouse dissonance for people who are from different cultures. For East Asians and people from other collectivistic cultures that value interdependence, public displays of inconsistency should arouse more dissonance, because harmonious connections with others are so important to them. To test this idea, Kitayama and colleagues (2004) had Western and East Asian students engage in a free-

194

Applications of Dissonance Theory

Induced Hypocrisy

Think ABOUT

Outside the social psychology lab, it would be tricky to get people to engage in counterattitudinal actions and still feel they had a choice. So if you wanted to use what you’ve learned about dissonance to change people’s attitudes and behavior for the sake of public health or the environment, how could you pull that off?

To achieve this goal, in the early 1990s, Elliot Aronson, Jeff Stone, and their colleagues came up with an induced hypocrisy paradigm. In this situation, people are asked to publicly advocate a position they already believe in but, to arouse dissonance, the experimenters remind them of a time when their actions ran counter to that position. In one study the researchers asked one group of sexually active students to make a short, videotaped speech for high-

Induced hypocrisy paradigm

A laboratory situation in which participants are asked to advocate an opinion they already believe in, but then are reminded about a time when their actions ran counter to that opinion, thereby arousing dissonance.

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Dissonance Can Make for Better Soldiers

Dissonance Can Make for Better Soldiers

The motive to maintain consistency in the self can have lasting effects on commitment to important life choices. Consider the situation that many young American men were in during the Vietnam War. When they turned 18, they would find out their draft lottery number, from 1 to 365, based randomly on their birthdate. A low number meant a good chance of having to fight in Vietnam. A high number meant they would not be drafted. But they could avoid the draft lottery entirely if they committed to six years of Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) service before the draft lottery numbers for their year were announced. This would mean military service, but they would remain in the United States rather than going to war.

The researcher Barry Staw (1974) studied men who chose the ROTC and how dissonance affected satisfaction with their choice. He reasoned that men who chose to join the ROTC, only to learn that they would not have been drafted anyway because of their high lottery number, would experience a lot of dissonance about their six-

How did the guys in the first situation reduce the dissonance they felt? Staw predicted that the men who found out their lottery numbers would have been high would reduce their dissonance by liking the ROTC more. In support of this hypothesis, he found that these men increased the value they placed on their ROTC training and became better soldiers (as judged by their commanding officers) than the men who knew that the ROTC kept them from combat in Vietnam. The men who could not justify their commitment to the ROTC by saying, “Well, it’s better than going to war” had to find some other way to justify their decision. They did this by becoming happier and better soldiers. Because the draft-

195

Effort Justification: Loving What We Suffer For

One implication Festinger drew from dissonance theory is that “people come to believe in and to love the things they suffer for.” In other words, when people choose a course of action that involves unpleasant effort, suffering, and pain, they experience dissonance because of the costs of that choice. Because they usually can’t go back and change their behavior, they reduce dissonance by convincing themselves that what they suffered for is actually quite valuable; this phenomenon is known as effort justification.

Effort justification

The phenomenon whereby people reduce dissonance by convincing themselves that what they suffered for is actually quite valuable.

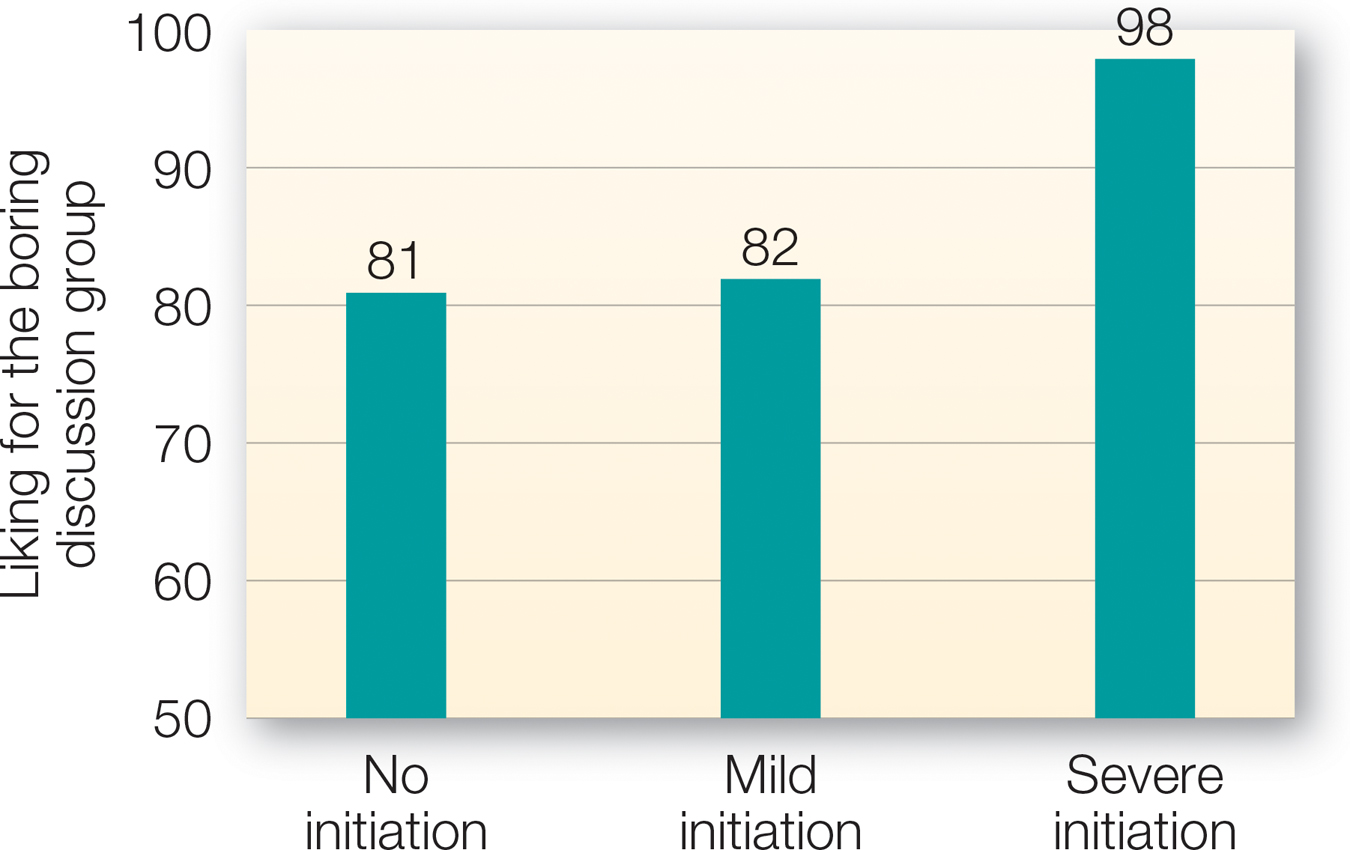

Elliot Aronson and Jud Mills (1959) tested this idea in a study that was inspired by fraternity initiation practices. They proposed that people who go through these initiations reduce their dissonance in the face of the effort and humiliation that is sometimes involved by becoming fonder of and more committed to those organizations. If this is true, then all other things being equal, the more severe the initiation to gain inclusion in the group, the more the group should be liked.

To test this hypothesis, they asked female students if they wanted to join a group that met regularly to discuss sexual matters. But depending on what condition the students were assigned to, gaining entry into the group required different levels of severity of initiation. In a control condition, the young women were immediately added to the group. In the mild initiation condition, participants had to read some mildly sexual words, such as virgin, in front of the male experimenter to join the group. In the severe initiation condition, they had to read some sexually explicit terms and then read a passage of explicit pornography in front of the experimenter. Imagine how difficult and embarrassing that would have been to young female college students back in 1959.

FIGURE 6.4

The Severity of Initiation Study: Evidence of Effort Justification

Participants expressed particularly high liking for a group if they had to go through a severe initiation to join the group. According to cognitive dissonance theory, they did this to justify the effort of having gone through the severe initiation.

[Data source: Aronson © Mills (1959)]

196

Once accepted into the group, participants were told that the group discussion was about to start but that as new members getting acclimated, they would just listen in. The women were ushered to private rooms and given headphones, then listened to what turned out to be a dreadfully boring discussion of the sex habits of insects. The women were then asked how much they liked the group discussion and how committed they were to the discussion group. As the graph in FIGURE 6.4 shows, the women who had to go through nothing or only a mild initiation were not impressed with the discussion and also were not highly committed to the group. In contrast, the severe initiation group, who had to go through a lot to get accepted, justified their effort by rating the discussion and their commitment to the group much more positively. These findings and others like them have clear implications for organizational practices and group loyalty. Could this be why so many organizations go out of their way to put new recruits through the wringer?

Parents try to deter a lot of their children’s behaviors, in this case, pulling the dog’s tail.

[Ron Nickel/Getty Images]

Might effort justification also play a role in the outcome of psychotherapy? Joel Cooper (1980) investigated whether a sense of choice would make an effortful therapy more effective. He gave participants with a severe snake phobia either a real form of therapy or a bogus one involving exercise, and he gave them either a high or low sense of choice. Compared with those who were not given a choice, participants who felt they freely chose the effortful therapy actually showed reduced phobia: They were able to move 10 feet closer to a snake than those who had the therapy without a sense of having chosen to participate in it. And the bogus therapy worked just as well as the real one; the only thing that mattered was the participants’ sense of having chosen to go through the effort. In a sense, to justify the effort, the participants made themselves improve.

Although neither Cooper nor we are suggesting that dissonance reduction is the only reason that psychotherapy can work, it may be one way patients can help themselves. The practical implication is that the client’s choice in participating in the therapy may help motivate positive change. This may explain why court-

Minimal Deterrence: Advice for Parenting

In the course of raising children, parents inevitably have to stop them from acting on many of their natural impulses, usually to deter them from doing things that are harmful or socially inappropriate. (“Don’t put that in your mouth!” “Stop sitting on your sister!”) A typical strategy that parents use to deter a child from misbehaving is to threaten with negative consequences such as spanking and grounding from video games. In these cases the child has a strong external justification for not doing the behavior (“I don’t want to get spanked!”), but this doesn’t mean that the child loses the desire to do the behavior. A better way to deter the behavior would be to use the minimal level of external justification necessary—

197

To test this idea, Aronson and Carlsmith (1963) developed a way to study the effects of minimal deterrence. They had four-

Minimal deterrence

Use of the minimal level of external justification necessary to deter unwanted behavior.

During this temptation period, the children were watched through a one-

Dissonance as Motivation

The preceding sections showcase some of the many ways that cognitive dissonance can impact our thoughts and behavior as we strive for self-

198

Self-consistency at the Macro Level: Sustaining a Sense of the Self as a Unified Whole

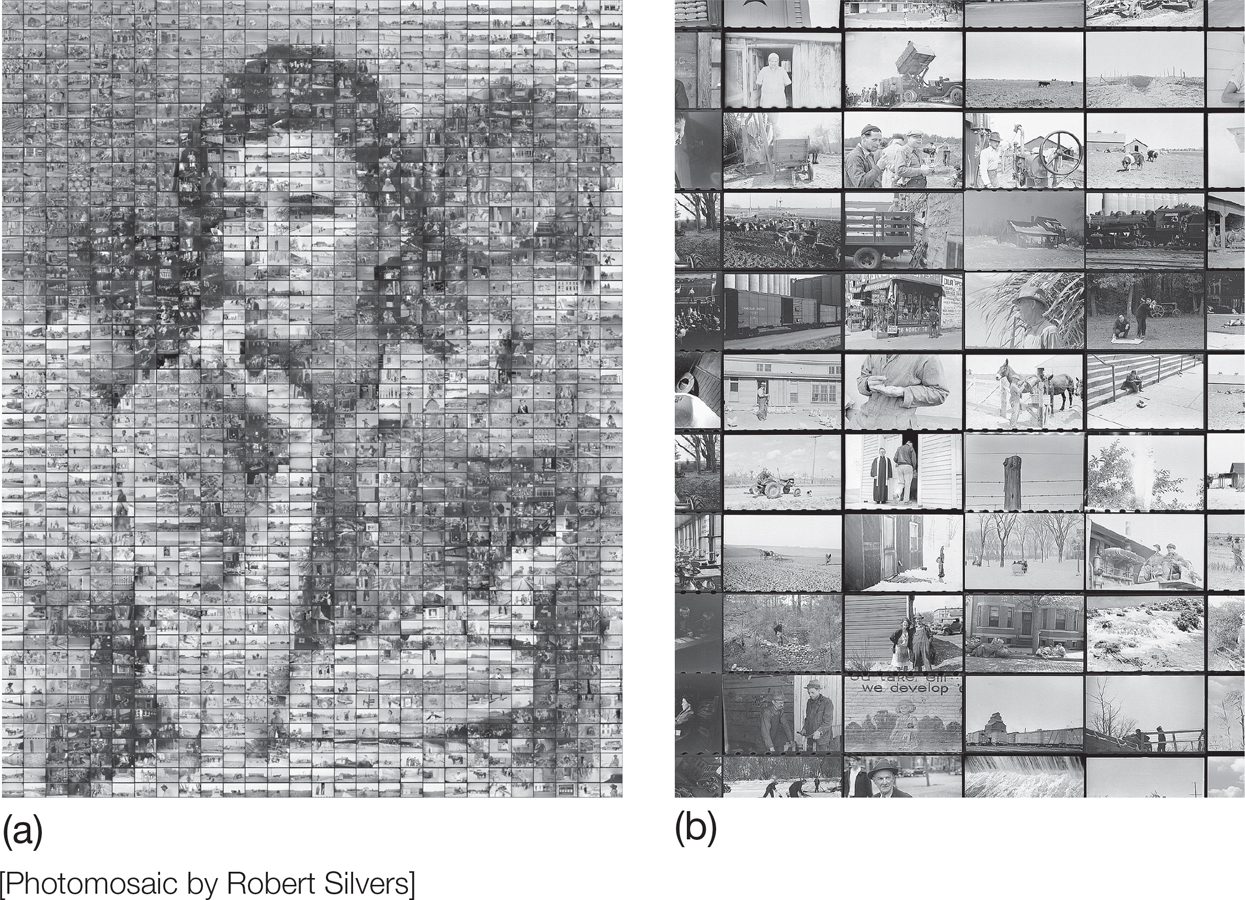

FIGURE 6.5

Dorothea Lange’s Classic Photo: Migrant Mother, Nipomo, Calif.

Dorothea Lange’s photograph powerfully captures one woman’s struggles during the Great Depression. Many years later, Robert Silvers replicated this iconic image in a photo-

[Photomosaic by Robert Silvers]

The picture on the left (FIGURE 6.5a) is a rendition of Dorothea Lange’s classic photograph Migrant Mother, Nipomo, Calif. If we squint our eyes or look at the picture from a distance, we can make out a young mother with an expression of deep concern as her children huddle around her. And when we learn that this picture was taken during the Great Depression, we can imagine this woman’s life struggle to care for herself and her family. But looking closer, we discover that the image is made up of hundreds of tiny photographs of assorted aspects of this woman’s surroundings, such as a door and a weather vane (FIGURE 6.5b). Although these tiny images make up the broader image, none of them captures the emotional significance of this woman’s life as clearly as the broader perspective does.

In a similar sense, the question of identity—

Self-consistency Across Situations

If you were to describe yourself in a personal ad right now, you might use characteristics like ambitious, cooperative, and shy. But do you always think and act in line with these broad traits? For example, you may think of yourself as introverted. But if you dredge up a different set of experiences—

Despite such inconsistencies, most people prefer self-

Self-concept clarity

A clearly defined, internally consistent, and temporally stable self-

One way people sustain a clear self-

People also tend to seek out others and social situations that confirm the way they view themselves, a phenomenon known as self-

Self-verification

Seeking out other people and social situations that support the way one views oneself in order to sustain a consistent and clear self-

199

Although self-

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Research on self-

Self-complexity

The extent to which an individual’s self-

My Story: Self-consistency Across Time

To tie together separate pieces of experience over time into a coherent whole, each person constructs a self-

Self-narrative

A coherent life story that connects one’s past, present, and possible future.

A clear self-

Think ABOUT

Dan McAdams (2006) found that middle-

Research on nostalgia helps us understand why it can be such an effective advertising tool (Holbrook, 1993). When an advertisement conjures up positive associations of a past self, people are more favorable to that product. This is why ads often pair products with cues that were nostalgically popular among those likely to be purchasing the product (e.g., classic rock music with commercials for mini-

[PR NewsFoto/Pepsi-

Research supports the idea that a need for psychological security motivates people to integrate their personal past and present into a coherent story. For example, Landau and colleagues (2009) showed that after a reminder of death, participants attempted to restore psychological security by seeing their past experiences as meaningfully connected to the person they are now, rather than as isolated events. Related studies show that whereas participants typically saw life as less meaningful after being reminded of death, this was not the case for participants who were prompted to think nostalgically about the past (Routledge et al., 2008). These individuals were able to use their perceptions of the past as a psychological shield against mortality, bolstering their conception that their own life has enduring significance.

200

Researchers have also found that although nostalgia can be bittersweet, overall it serves a number of positive psychological functions: It generates positive moods, boosts self-

Because self-

APPLICATION: Stories That Heal

|

APPLICATION: |

| Stories That Heal |

The healing power of working through past traumas was emphasized by psychoanalysts such as Freud and has been supported by experimental studies by Jamie Pennebaker and colleagues. In one such study, people who wrote about an emotionally traumatic experience for four days, just 15 minutes a day, showed marked improvements in physical health (e.g., fewer physician visits for illness) many months later (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986).

How does narrating a traumatic event help with coping? Pennebaker and colleagues (1997) developed a computer program to analyze the language that individuals use while disclosing emotional topics. They found that people who narrated the trauma using words associated with seeking insight and cause-

Not only do self-

APPLICATION: Educational Achievement

|

APPLICATION: |

| Educational Achievement |

Personal narratives also include possible selves, vivid images of what the self might become in the future. Some possible selves are positive (“the successful designer me,” “the party animal me”), whereas others are negative (“the unemployed me,” “the lonely me”). Possible selves give a face to a person’s goals, aspirations, fears, and insecurities. For example, your personal goal of succeeding in college probably is not some vague abstraction but more likely takes shape in your mind as a vivid image of a positive possible self, “academic star me,” up on stage receiving a prestigious award as your classmates look on in admiration.

Possible selves

Images of what the self might become in the future.

201

Our visions of possible selves are not just idle pictures in our minds. They also motivate and guide our behavior (Markus & Nurius, 1986). That’s because thinking about a possible self can make us aware of the actions we need to take now in order to become that person in the future. In one demonstration of this, Daphna Oyserman and colleagues (2006) went into low-

|

The Motive to Maintain a Consistent Self |

|

Cognitive dissonance theory explains that, at the micro level, people maintain self- |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Free Choice Paradigm

|

Induced Compliance Paradigm People induced to say or do something against their beliefs may change their beliefs to reduce dissonance if there is insufficient external justification for their behavior. |

Factors That Affect the Magnitude of Dissonance Dissonance increases with less external justification and more perceived choice, commitment, and foreseeable negative consequences. |

Cultural Influence In cultures that value interdependence, public displays of inconsistency arouse more dissonance because harmonious relationships are so valued. |

|

Applications

|

|||

|

At the macro level, self- |

|||

|

Self- Self- |

Self- A complex self- |

Self- Self- |

|

|

Application: Talking or writing about a painful event can help a person cope with stressful experiences. |

|||

|

Application: Envisioning possible selves can help motivate people to achieve their long- |

|||

202