America’s History: Printed Page 961

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 874

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 852

Religion in the 1970s: The Fourth Great Awakening

For three centuries, American society has been punctuated by intense periods of religious revival — what historians have called Great Awakenings (see “American Pietism and the Great Awakening” in Chapter 4 and “The Second Great Awakening” in Chapter 8). These periods have seen a rise in church membership, the appearance of charismatic religious leaders, and the increasing influence of religion, usually of the evangelical variety, on society and politics. One such awakening, the fourth in U.S. history, took shape in the 1970s and 1980s. It had many elements, but one of its central features was a growing concern with the family.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many mainstream Protestants had embraced the reform spirit of the age. Some of the most visible Protestant leaders were social activists who condemned racism and opposed the Vietnam War. Organizations such as the National Council of Churches — along with many progressive Catholics and Jews — joined with Martin Luther King Jr. and other African American ministers in the long battle for civil rights. Many mainline Protestant churches, among them the Episcopal, Methodist, and Congregationalist denominations, practiced a version of the “Social Gospel,” the reform-minded Christianity of the early twentieth century.

Evangelical Resurgence Meanwhile, evangelicalism survived at the grass roots. Evangelical Protestant churches emphasized an intimate, personal salvation (being “born again”); focused on a literal interpretation of the Bible; and regarded the death and resurrection of Jesus as the central message of Christianity. These tenets distinguished evangelicals from mainline Protestants as well as from Catholics and Jews, and they flourished in a handful of evangelical colleges, Bible schools, and seminaries in the postwar decades.

No one did more to keep the evangelical fire burning than Billy Graham. A graduate of the evangelical Wheaton College in Illinois, Graham cofounded Youth for Christ in 1945 and then toured the United States and Europe preaching the gospel. Following a stunning 1949 tent revival in Los Angeles that lasted eight weeks, Graham shot to national fame. His success in Los Angeles led to a popular radio program, but he continued to travel relentlessly, conducting old-fashioned revival meetings he called crusades. A massive sixteen-week 1957 crusade held in New York City’s Madison Square Garden made Graham, along with the conservative Catholic priest Fulton Sheen, one of the nation’s most visible religious leaders.

Graham and other evangelicals in the 1950s and 1960s laid the groundwork for the Fourth Great Awakening. But it was a startling combination of events in the late 1960s and early 1970s that sparked the evangelical revival. First, rising divorce rates, social unrest, and challenges to prevailing values led people to seek the stability of faith. Second, many Americans regarded feminism, the counterculture, sexual freedom, homosexuality, pornography, and legalized abortion not as distinct issues, but as a collective sign of moral decay in society. To seek answers and find order, more and more people turned to evangelical ministries, especially Southern Baptist, Pentecostal, and Assemblies of God churches.

Numbers tell part of the story. As mainline churches lost about 15 percent of their membership between 1970 and 1985, evangelical church membership soared. The Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination, grew by 23 percent, while the Assemblies of God grew by an astounding 300 percent. Newsweek magazine declared 1976 “The Year of the Evangelical,” and that November the nation made Jimmy Carter the nation’s first evangelical president. In a national Gallup poll, 34 percent of Americans answered yes when asked, “Would you describe yourself as a ‘born again’ or evangelical Christian?”

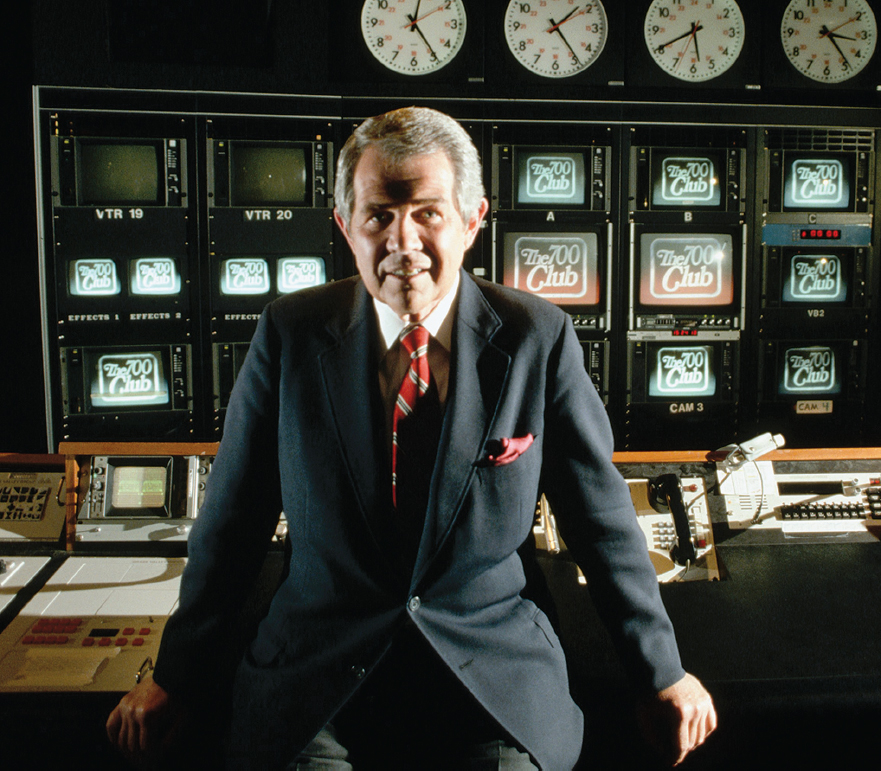

Much of this astonishing growth came from the creative use of television. Graham had pounded the pavement and worn out shoe leather to reach his converts. But a new generation of preachers brought religious conversion directly into Americans’ living rooms through television. These so-called televangelists built huge media empires through small donations from millions of avid viewers — not to mention advertising. Jerry Falwell’s Old Time Gospel Hour, Pat Robertson’s 700 Club, and Jim and Tammy Bakker’s PTL (Praise the Lord) Club were the leading pioneers in this televised race for American souls, but another half dozen — including Oral Roberts and Jimmy Swaggart — followed them onto the airwaves. Together, they made the 1970s and 1980s the era of Christian broadcasting.

Religion and the Family Of primary concern to evangelical Christians was the family. Drawing on selected Bible passages, evangelicals believed that the nuclear family, and not the individual, represented the fundamental unit of society. The family itself was organized along paternalist lines: father was breadwinner and disciplinarian; mother was nurturer and supporter. “Motherhood is the highest form of femininity,” the evangelical author Beverly LaHaye wrote in an influential book on Christian women. Another popular Christian author declared, “A church, a family, a nation is only as strong as its men.”

Evangelicals spread their message about the Christian family through more than the pulpit and television. They founded publishing houses, wrote books, established foundations, and offered seminars. Helen B. Andelin, for instance, a California housewife, produced a homemade book called Fascinating Womanhood that eventually sold more than 2 million copies. She used the book as the basis for her classes, which by the early 1970s had been attended by 400,000 women and boasted 11,000 trained teachers. Fascinating Womanhood led evangelical women in the opposite direction of feminism. Whereas the latter encouraged women to be independent and to seek equality with men, Andelin taught that “submissiveness will bring a strange but righteous power over your man.” Andelin was but one of dozens of evangelical authors and educators who encouraged women to defer to men.

Evangelical Christians held that strict gender roles in the family would ward off the influences of an immoral society. Christian activists were especially concerned with sex education in public schools, the proliferation of pornography, legalized abortion, and the rising divorce rate. For them, the answer was to strengthen what they called “traditional” family structures. By the early 1980s, Christians could choose from among hundreds of evangelical books, take classes on how to save a marriage or how to be a Christian parent, attend evangelical churches and Bible study courses, watch evangelical ministers on television, and donate to foundations that promoted “Christian values” in state legislatures and the U.S. Congress.

Wherever one looked in the 1970s and early 1980s, American families were under strain. Nearly everyone agreed that the waves of social liberalism and economic transformation that swept over the nation in the 1960s and 1970s had destabilized society and, especially, family relationships. But Americans did not agree about how to restabilize families. Indeed, different approaches to the family would further divide the country in the 1980s and 1990s, as the New Right would increasingly make “family values” a political issue.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did evangelical Christianity influence American society in the 1970s?