Introduction to Chapter 21

21

The Twenties

1919–1929

WINDOW TO THE PAST

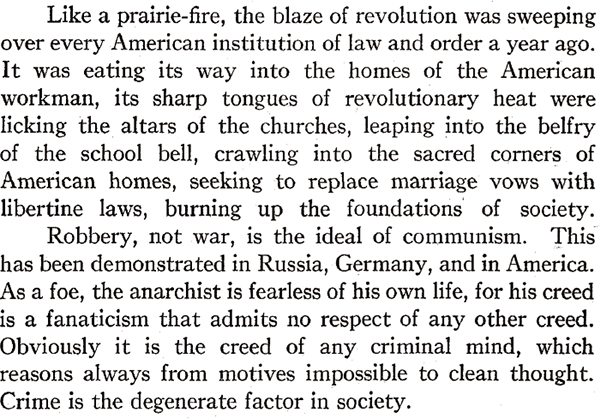

The Case against the Reds, 1920

The panic over the spread of Communism following World War I reflected underlying political, economic, and social fears in the nation. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer justified the roundup and deportation of immigrant radicals as essential to stopping the spread of Communism. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 21.1.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the nature and causes of the anti-communist panic, labor unrest, and escalating racial tensions following World War I.

Describe the economic impact of the second industrial revolution, the creation of the consumer culture, urbanization, and the role the federal government played in promoting economic expansion.

Analyze how white and black popular culture challenged traditional morality and gender roles.

Describe the tensions between nativists and immigrants and fundamentalism and modernism, and how these culture wars were manifested by the activity of the federal government and private organizations.

Explain the dominance of the Republican Party over the Progressive and Democratic parties and the political flaws that led to the Great Depression.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

David Curtis (D. C.) Stephenson’s pursuit of the American dream kept him on the move. Born in 1891 to Texas sharecroppers, Stephenson moved with his family to the Oklahoma Territory in 1901. After quitting school at age sixteen, he drifted around for more than a decade, working for a string of newspapers and gaining a reputation as a heavy drinker. In 1915 he married and appeared to settle down; however, he soon lost his newspaper job, abandoned his pregnant wife, and hit the road working for one newspaper after another in between binges of drunkenness. His wife divorced him, and in 1917 Stephenson joined the army to fight in World War I. Despite a series of drunken brawls and sexual misadventures, he received an honorable discharge in 1919.

Stephenson remarried and settled in Indiana, where he found financial and political success. In 1920 he joined the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), the Reconstruction-era organization that had reemerged in 1915 in Georgia. The newly revived Klan spread beyond the South, targeting African Americans, recent immigrants, Jews, and Catholics as enemies of traditional Protestant family values. Stephenson directed Klan operations in twenty-three states, building a profitable empire on fear, prejudice, and get-rich-quick schemes. A few years later, however, his Klan career ended with his arrest and conviction on rape and second-degree murder charges.

Ossian Sweet also pursued the American dream. Like Stephenson, he rose from humble beginnings. The descendant of slaves, Sweet was born in 1895 and grew up in central Florida. Hoping to shield him from the violence that whites used to keep blacks in their place, Sweet’s parents sent him north when he was thirteen years old.

After attending Wilberforce University in Ohio and Howard Medical School in Washington, D.C., Sweet moved to Detroit in 1921 to open a medical practice. He married, and in 1924 the Sweets decided to buy a house in a working-class neighborhood occupied exclusively by whites. Before the Sweets moved in, their white neighbors, with Klan backing, began organizing to keep them out.

When the Sweet family moved into their house on September 8, 1925, they encountered a hostile crowd in the street. Dr. Sweet had brought some backup with him. Armed to resist the mob, the Sweets and their defenders fired their weapons at the crowd after rocks smashed through the upstairs windows of the house. When the shooting stopped and the police restored calm, one white man lay dead and another wounded. Dr. Sweet; his wife, Gladys; and the other nine occupants of his house went on trial on first-degree murder charges. Hired by the NAACP, Clarence Darrow represented the eleven defendants and after two trials—the first ended in a hung jury—won an acquittal in 1926.

The American histories of Ossian Sweet and D. C. Stephenson illustrate the competing forces that shaped the 1920s. Both men achieved a measure of financial success, but they did so in the post–World War I atmosphere of growing social friction and intense racial resentments. When Sweet’s parents decided to send him north, they were responding to the racial violence that plagued the South, but they were also demonstrating their belief that a better life was possible for their son. By contrast, Stephenson grew wealthy by tapping into the same racial tensions that shaped the Sweets’ lives. Many whites who considered themselves “100 percent Americans,” born and bred in small towns or living in sections of cities with homogeneous populations, believed that racial and ethnic minorities threatened their power. The fear of Communist infiltration heightened their concerns over immigration, and changes in morality and gender roles further raised their fears. Although the general prosperity of the period masked the tensions lying beneath the surface, it did not eliminate them. Rampant consumerism concealed the unequal prosperity fostered by Republican policies that later led to the Great Depression. As the experiences of D. C. Stephenson and Ossian Sweet show, the decade following the end of World War I opened up fresh avenues for economic prosperity as well as new sites for cultural clashes exacerbated by the tensions of modern America.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 683

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 504

Chapter Timeline