11.5 The Trait Perspective on Personality

KEY THEME

Trait theories of personality focus on identifying, describing, and measuring individual differences.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are traits, and how do surface traits and source traits differ?

What are three influential trait theories, and how might heredity affect personality?

What are the key strengths and weaknesses of trait theories of personality?

Suppose we asked you to describe the personality of a close friend. How would you begin? Would you describe her personality in terms of her unconscious conflicts, the congruence of her self-concept, or her level of self-efficacy? Probably not. Instead, you’d probably generate a list of her personal characteristics, such as “outgoing,” “cheerful,” and “generous.” This rather commonsense approach to personality is shared by the trait theories. The trait approach to personality is very different from the theories we have encountered thus far. The psychoanalytic, humanistic, and social cognitive theories emphasize the similarities among people. They focus on discovering the universal processes of motivation and development that explain human personality (Revelle, 1995, 2007). Although these theories do deal with individual differences, they do so only indirectly. In contrast, the trait approach to personality focuses primarily on describing individual differences (Funder & Fast, 2010).

Trait theorists view the person as being a unique combination of personality characteristics or attributes, called traits. A trait is formally defined as a relatively stable, enduring predisposition to behave in a certain way. A trait theory of personality, then, is one that focuses on identifying, describing, and measuring individual differences in behavioral predispositions. Think back to our description of the twins, Kenneth and Julian, in the chapter Prologue. You can probably readily identify some of their personality traits. For example, Julian was described as impulsive, cocky, and adventurous, while Kenneth was serious, intense, and responsible.

trait

A relatively stable, enduring predisposition to consistently behave in a certain way.

trait theory

A theory of personality that focuses on identifying, describing, and measuring individual differences in behavioral predispositions.

People possess traits to different degrees. For example, a person might be extremely shy, somewhat shy, or not shy at all. Hence, a trait is typically described in terms of a range from one extreme to its opposite. Most people fall in the middle of the range (average shyness), while fewer people fall at opposite poles (extremely shy or extremely outgoing).

Surface Traits and Source Traits

Most of the terms that we use to describe people are surface traits—traits that lie on “the surface” and can be easily inferred from observable behaviors. Examples of surface traits include attributes like “happy,” “exuberant,” “spacey,” and “gloomy.” The list of potential surface traits is extremely long. Personality researcher Gordon Allport combed through an English-language dictionary and discovered more than 4,000 words that described specific personality traits (Allport & Odbert, 1936).

surface traits

Personality characteristics or attributes that can easily be inferred from observable behavior.

Source traits are thought to be more fundamental than surface traits. As the most basic dimension of personality, a source trait can potentially give rise to a vast number of surface traits. Trait theorists believe that there are relatively few source traits. Thus, one goal of trait theorists has been to identify the most basic set of universal source traits that can be used to describe all individual differences (Pervin, 1994).

source traits

The most fundamental dimensions of personality; the broad, basic traits that are hypothesized to be universal and relatively few in number.

Two Representative Trait Theories

RAYMOND CATTELL AND HANS EYSENCK

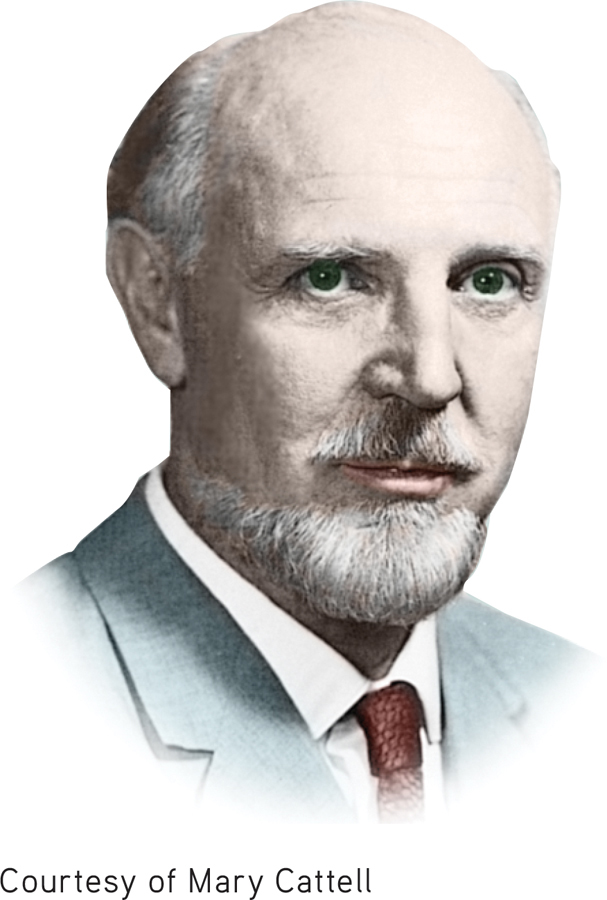

How many source traits are there? Not surprisingly, trait theorists differ in their answers. Pioneer trait theorist Raymond Cattell reduced Allport’s list of 4,000 terms to about 171 characteristics by eliminating terms that seemed to be redundant or uncommon (see John, 1990). Cattell collected data on a large sample of people, who were rated on each of the 171 terms. He then used a statistical technique called factor analysis to identify the traits that were most closely related to one another. After further research, Cattell eventually reduced his list to 16 key personality factors, which are listed in TABLE 11.3.

Cattell’s 16 Personality Factors

| 1 Reserved, unsociable |

|

Outgoing, sociable |

| 2 Less intelligent, concrete |

|

More intelligent, abstract |

| 3 Affected by feelings |

|

Emotionally stable |

| 4 Submissive, humble |

|

Dominant, assertive |

| 5 Serious |

|

Happy-go-lucky |

| 6 Expedient |

|

Conscientious |

| 7 Timid |

|

Venturesome |

| 8 Tough-minded |

|

Sensitive |

| 9 Trusting |

|

Suspicious |

| 10 Practical |

|

Imaginative |

| 11 Forthright |

|

Shrewd, calculating |

| 12 Self-assured |

|

Apprehensive |

| 13 Conservative |

|

Experimenting |

| 14 Group-dependent |

|

Self-sufficient |

| 15 Undisciplined |

|

Controlled |

| 16 Relaxed |

|

Tense |

| Raymond Cattell believed that personality could be described in terms of 16 source traits, or basic personality factors. Each factor represents a dimension that ranges between two extremes. | ||

Cattell (1994) believed that these 16 personality factors represent the essential source traits of human personality. To measure these traits, Cattell developed what has become one of the most widely used personality tests, the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (abbreviated 16PF). We’ll discuss the 16PF in more detail later in the chapter.

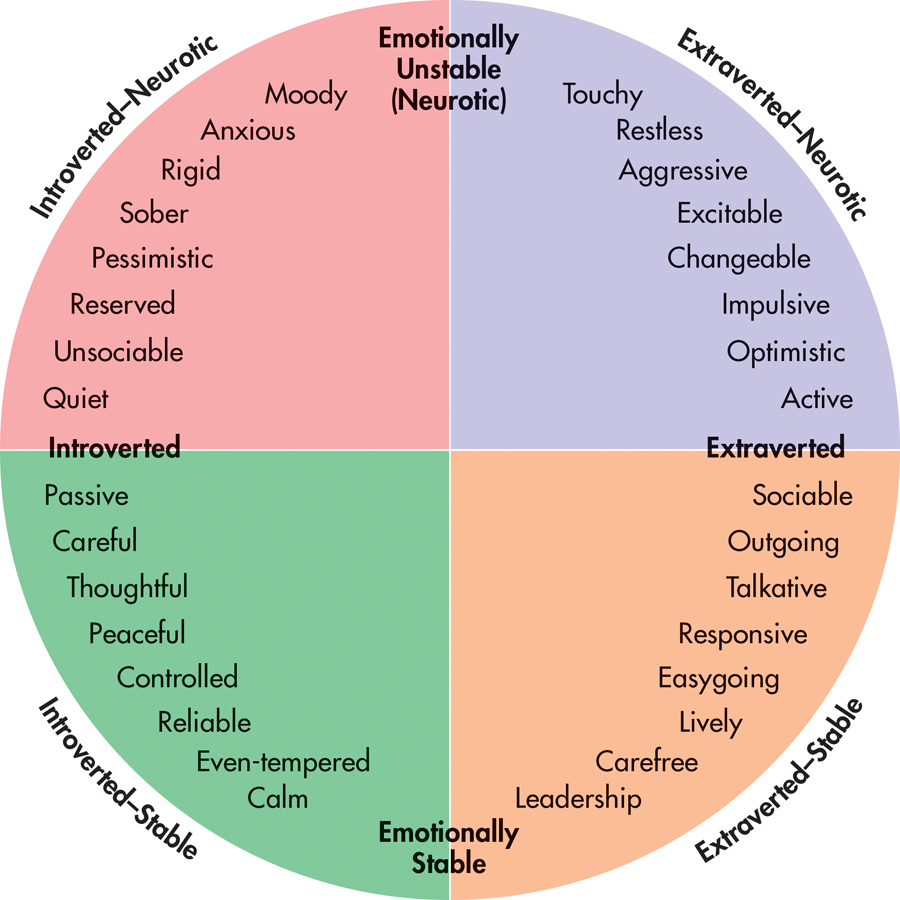

An even simpler model of universal source traits was proposed by British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1916–

Eysenck’s second major dimension is neuroticism–

Eysenck believed that by combining these two dimensions, people can be classified into four basic types: introverted–

In later research, Eysenck identified a third personality dimension, called psychoticism (Eysenck, 1990; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). A person high on this trait is antisocial, cold, hostile, and unconcerned about others. A person who is low on psychoticism is warm and caring toward others. In the chapter Prologue, Julian might be described as above average on psychoticism, while Kenneth was extremely low on this trait.

Eysenck (1990) believed that individual differences in personality are due to biological differences among people. For example, Eysenck proposed that an introvert’s nervous system is more easily aroused than is an extravert’s nervous system. Assuming that people tend to seek out an optimal level of arousal (see Chapter 8), extraverts would seek stimulation from their environment more than introverts would. And, because introverts would be more uncomfortable than extraverts in a highly stimulating environment, introverts would be much less likely to seek out stimulation.

Do introverts and extraverts actually prefer different environments? In a clever study, John Campbell and Charles Hawley (1982) found that extraverted students tended to study in a relatively noisy, open area of a college library, where there were ample opportunities for socializing with other students. Introverted students preferred to study in a quiet section of the library, where individual carrels and small tables were separated by tall bookshelves. As Eysenck’s theory predicts, the introverts preferred study areas that minimized stimulation, while the extraverts preferred studying in an area that provided stimulation.

Sixteen Are Too Many, Three Are Too Few

THE FIVE-FACTOR MODEL

Many trait theorists felt that Cattell’s trait model was too complex and that his 16 personality factors could be reduced to a smaller, more basic set of traits. Yet Eysenck’s three-dimensional trait theory seemed too limited, failing to capture other important dimensions of human personality (see Block, 1995).

Today, the consensus among many trait researchers is that the essential building blocks of personality can be described in terms of five basic personality dimensions, which are sometimes called “the Big Five” (Funder, 2001). According to the five-factor model of personality, these five dimensions represent the structural organization of personality traits (McCrae & Costa, 1996, 2003).

five-factor model of personality

A trait theory of personality that identifies extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience as the fundamental building blocks of personality.

What are the Big Five? Different trait researchers describe the five basic traits somewhat differently. However, the most commonly accepted five factors are extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. TABLE 11.4 summarizes the Big Five traits as defined by personality theorists Robert McCrae and Paul Costa, Jr. Note that Factor 1, neuroticism, and Factor 2, extraversion, are essentially the same as Eysenck’s first two personality dimensions.

The Five-Factor Model of Personality

Low

|

High |

|---|---|

| Factor 1: Neuroticism | |

| Calm Even-tempered, unemotional Hardy |

Worrying Temperamental, emotional Vulnerable |

| Factor 2: Extraversion | |

| Reserved Loner Quiet |

Affectionate Joiner Talkative |

| Factor 3: Openness to Experience | |

| Down-to-earth Conventional, uncreative Prefer routine |

Imaginative Original, creative Prefer variety |

| Factor 4: Agreeableness | |

| Antagonistic Ruthless Suspicious |

Acquiescent Softhearted Trusting |

| Factor 5: Conscientiousness | |

| Lazy Aimless Quitting |

Hardworking Ambitious Persevering |

| Source: Research from McCrae & Costa (1990). | |

| This table shows the five major personality factors, according to Big Five theorists Robert McCrae and Paul Costa, Jr. Listed below each major personality factor are surface traits that are associated with it. Note that each factor represents a dimension or range between two extreme poles. Most people will fall somewhere in the middle between the two opposing poles. | |

Use the acronym OCEAN to help you remember the five factors.

Does the five-factor model describe the universal structure of human personality? According to ongoing research by Robert McCrae and his colleagues (2004, 2005), the answer appears to be yes. In one wide-ranging study, trained observers rated the personality traits of representative individuals in 50 different cultures, including Arab cultures like those in Kuwait and Morocco and African cultures like those in Uganda and Ethiopia (McCrae & others, 2005). With few exceptions, people could be reliably described in terms of the five-factor structure of personality. Other research has shown that people in European, African, Arab, and Asian cultures describe personality using terms that are consistent with the five-factor model (Allik & McCrae, 2004; Rossier & others, 2005). Based on abundant cross-cultural research, trait theorists Jüri Allik and Robert McCrae (2002, 2004, 2013) believe that the Big Five personality traits are basic features of the human species, universal, and probably biologically based. Some personality researchers, however, are unconvinced, pointing out that there are culturally-specific patterns of behavior that do not easily fit the five-factor model (Carlo & others, 2014). And, recent evidence suggests that the five-factor model may not apply to pre-industrial, preliterate indigenous tribes and developing countries (Gurven & others, 2013). However, these findings seem to be the exception, not the rule.

How can we account for the apparent universality of the five-factor structure? Psychologist David Buss (1991, 1995a) has one intriguing explanation. Buss thinks we should look at the utility of these factors from an evolutionary perspective. He believes that the Big Five traits reflect the personality dimensions that are the most important in the “social landscape” to which humans have had to adapt. Being able to identify who has social power (extraversion), who is likely to share resources (agreeableness), and who is trustworthy (conscientiousness) enhances our likelihood of survival.

Research has shown that traits are remarkably stable over time. A young adult who is very extraverted, emotionally stable, and relatively open to new experiences is likely to grow into an older adult who could be described in much the same way (McCrae & Costa, 2006; McCrae & others, 2000). However, this is not to say that personality traits don’t change at all. Longitudinal data suggest that some general trends are evident over the lifespan. These include a slight decline in neuroticism, an increase in agreeableness and conscientiousness, and stability in extraversion and openness to experience from early to late adulthood (Soto & others, 2011; Kandler, 2012). In other words, most people become more dominant, agreeable, conscientious, and emotionally stable as they mature psychologically (Caspi & others, 2005; Roberts & others, 2006).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that personality traits change quite a bit over the course of our lives?

Traits are also generally consistent across different situations. However, situational influences may affect the expression of personality traits. Situations in which your behavior is limited by social “rules” or expectations may limit the expression of your personality characteristics. For example, even the most extraverted person may be subdued at a funeral. In general, behavior is most likely to reflect personality traits in familiar, informal, or private situations with few social rules or expectations (A. H. Buss, 1989, 2001).

Given the consistency of traits over time and across situations, many psychologists think that traits may be associated with specific patterns of brain activity or structure (Canli, 2004, 2006). We discuss a recent attempt to investigate the relationship between brain structure and personality traits in the Focus on Neuroscience box, “The Neuroscience of Personality: Brain Structure and the Big Five.”

Keep in mind, however, that human behavior is the result of a complex interaction between traits and situations (Mischel, 2004; Mischel & Shoda, 2010). People do respond, sometimes dramatically, to the demands of a particular situation. But the situations that people choose, and the characteristic way in which they respond to similar situations, are likely to be consistent with their individual personality dispositions (Mischel & Shoda, 1995; Mischel & others, 2002).

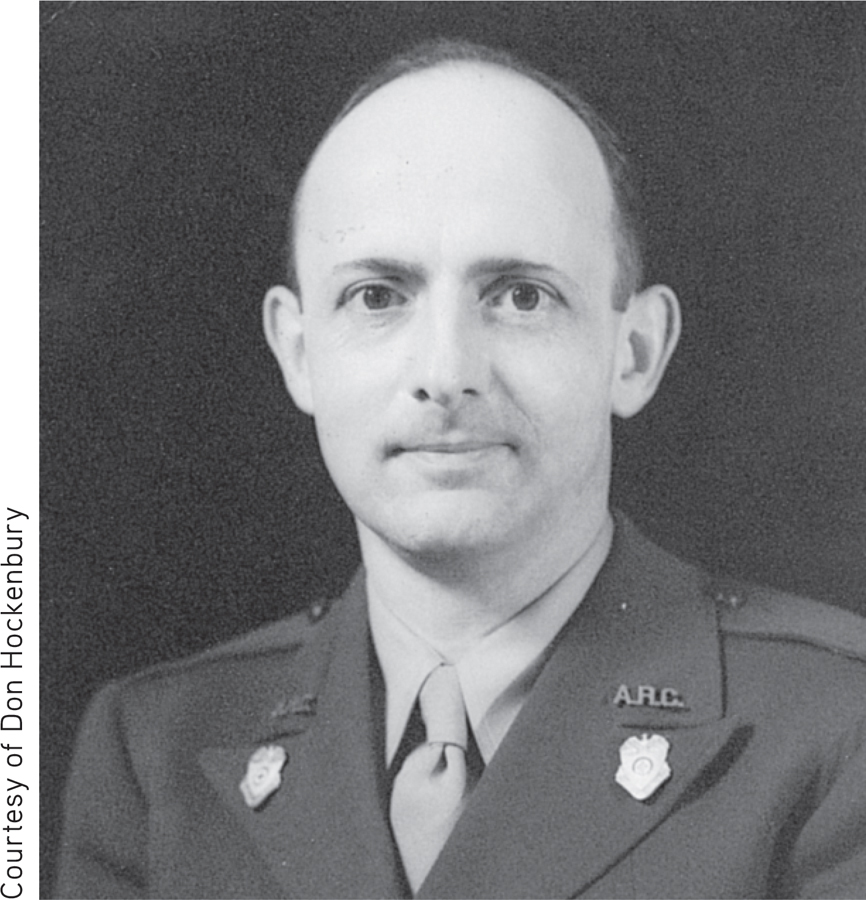

Personality Traits and Behavioral Genetics

JUST A CHIP OFF THE OLD BLOCK?

Do personality traits run in families? Are personality traits determined by genetics? Many trait theorists, such as Raymond Cattell and Hans Eysenck, believed that traits are at least partially genetic in origin. For example, Sandy and Don’s daughter, Laura, has always been outgoing and sociable, traits that she shares with both her parents. But is she outgoing because she inherited that trait? Or is she outgoing because outgoing behavior was modeled and reinforced? Is it even possible to sort out the relative influence that genetics and environmental experiences have on personality traits?

Behavioral genetics has documented, without a shadow of a remaining doubt, that personality is to some degree genetically influenced: Identical twins reared apart have similar traits. The tabula rasa view of personality as a blank slate at birth that is written upon by experience, for many years a basic assumption of theories of all stripes, is wrong.

—David C. Funder (2001)

The field of behavioral genetics studies the effects of genes and heredity on behavior. Most behavioral genetics studies on humans involve measuring similarities and differences among members of a large group of people who are genetically related to different degrees. The basic research strategy is to compare the degree of difference among subjects to their degree of genetic relatedness. If a trait is genetically influenced, then the more closely two people are genetically related, the more you would expect them to be similar on that trait (see Chapter 7).

behavioral genetics

An interdisciplinary field that studies the effects of genes and heredity on behavior.

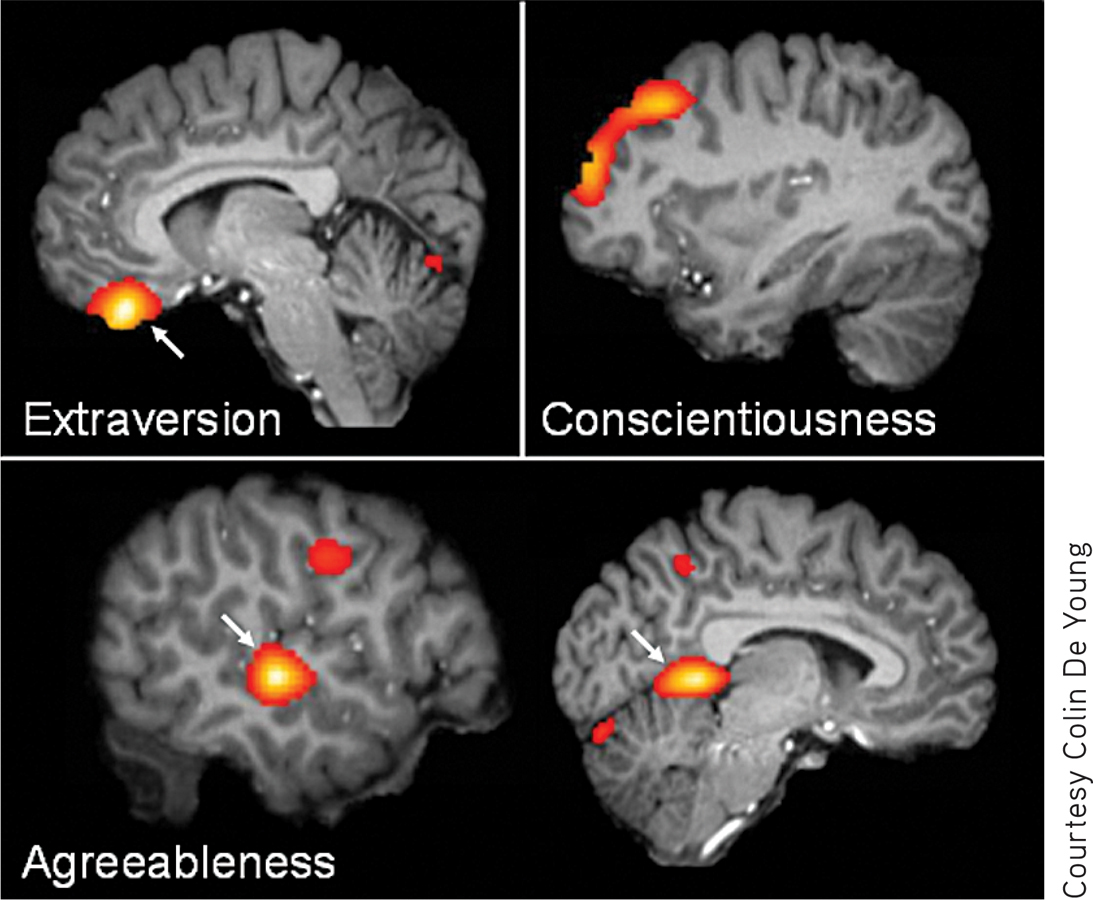

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

The Neuroscience of Personality: Brain Structure and the Big Five

Many personality theorists, like Hans Eysenck, believed that personality traits are associated with characteristic biological differences among people (DeYoung & Gray, 2009). Some studies have confirmed this belief, identifying distinct patterns of brain activity associated with different personality traits (Canli, 2004, 2006). For example, brain-imaging studies showed that people who were high in extraversion (Factor 2) showed higher levels of brain activation in response to positive images than people who were low in extraversion. Similarly, people who score high on Factor 1, neuroticism, show more activation in response to negative images than people who score low on neuroticism (Canli & others, 2001).

Are personality traits also associated with brain structure? Psychologist Colin DeYoung and his colleagues had over 100 male and female participants undergo MRI scans and also take the NEO-Personality Inventory, a personality test that is used to measure the Big Five. The researchers then compared the brain scans and the personality test results. They found:

Extraversion was associated with larger brain tissue volume in the medial orbitofrontal cortex, a brain region that is associated with sensitivity to rewarding stimuli.

Agreeableness was associated with increased volume in the posterior cingulate cortex, a brain region associated with understanding the beliefs of others (Saxe & Powell, 2006). It was also associated with greater volume in the fusiform gyrus, an area of the cortex specialized for perceiving faces (see Chapters 3 and 7).

Conscientiousness was associated with a large region of the frontal cortex called the middle frontal gyrus, which is known to be involved in planning, working memory, and self-regulation.

But not all personality traits had such clear correlations. Neuroticism was associated with a mixed pattern of brain structure differences. Higher levels of neuroticism were associated with reduced volume in one area of the hippocampus, a finding that has also been found in stress and depression (Bremner & others, 2000). Another region, the mid-cingulate cortex, which is believed to be associated with pain sensitivity, was larger. Taken together, the pattern of differences led the researchers to conclude that neuroticism is related to structural differences in brain systems related to sensitivity to threat and punishment.

Finally, DeYoung and his colleagues found no significant pattern of brain differences associated with openness to experience (Factor 5). They observed a slightly greater brain volume in one region that is associated with working memory and attention, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Are such studies merely phrenology with a modern face? These findings, while still preliminary, do suggest that there are biological influences on personality. It’s important to note, though, that the findings are correlational. It’s entirely possible that the brain differences are caused by different patterns of behavior rather than the other way around.

Further, unlike the phrenologists (see Chapter 2), today’s researchers are well aware that both brain differences and personality traits are shaped by the complex interaction of environmental, genetic, and biological influences. As DeYoung (2010b) says, the ultimate goal is to use the methods of neuroscience to help generate a new theory of personality—one in which personality is seen as a “system of dynamic, interacting elements that generates the ongoing flux of behavior and experience.”

Such studies may involve comparisons between identical twins and fraternal twins or comparisons between twins reared apart and identical twins reared together (see the In Focus box, “Explaining Those Amazing Identical-Twin Similarities” below). Adoption studies, in which adopted children are compared to their biological and adoptive relatives, are also used in behavioral genetics.

Evidence gathered from twin studies and adoption studies shows that certain personality traits are substantially influenced by genetics (Amin & others, 2011; de Moor & others, 2010; McCrae & others, 2010). The evidence for genetic influence is particularly strong for extraversion and neuroticism, two of the Big Five personality traits (Plomin & others, 1994, 2001; Weiss & others, 2008). Twin studies have also found that openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are also influenced by genetics, although to a lesser extent (Bouchard, 2004; Harris & others, 2007).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that personality is not influenced by genetics, but is primarily shaped by your upbringing?

IN FOCUS

Explaining Those Amazing Identical-Twin Similarities

As part of the ongoing Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart at the University of Minnesota, researchers David Lykken, Thomas Bouchard, and other psychologists have been studying a very unusual group of people: over 100 pairs of identical and fraternal twins who were separated at birth or in early childhood and raised in different homes. Shortly after the study began in 1980, the researchers were struck by some of the amazing similarities between identical twins (Lykken & others, 1992). Despite having been separated for most of their lives, many twins had similar personality traits, occupations, hobbies, and habits.

One of the most famous cases is that of the “Jim twins,” who had been separated for close to 40 years. Like many of the other reunited twins, the two Jims had similar heights, postures, and voice and speech patterns. More strikingly, both Jims had married and divorced women named Linda, and then married women named Betty. One Jim named his son James Allan, while the other Jim named his son James Alan. Both Jims bit their nails, chain-smoked Salems, and enjoyed working in their basement workshops. And both Jims had vacationed at the same Florida beach, driving there in the same model Chevrolet (Lykken & others, 1992).

Granted, such similarities could simply be due to coincidence. Linda, Betty, James, and Alan are not exactly rare names in the United States. And literally thousands of people buy the same model car every year, just as thousands of people vacation in Florida. Besides, if you look closely at any two people of the same age, sex, and culture, there are bound to be similarities. It’s probably a safe bet, for example, to say that most college students enjoy eating pizza and often wear jeans and T-shirts.

But it’s difficult to dismiss as mere coincidences all the striking similarities between identical twins in the Minnesota study. Lykken and his colleagues (1992) have pointed out numerous quirky similarities that occurred in the identical twins they studied but did not occur in the fraternal-twin pairs. For example, in the entire sample of twins, there were only two subjects who had been married five times; two subjects who habitually wore seven rings; and two who left love notes around the house for their wives. In each case, the two were identical twins. And only two subjects independently (and correctly) diagnosed a problem with researcher Bouchard’s car—a faulty wheel bearing. Again, the two were members of an identical-twin pair. While Lykken and his colleagues acknowledge that some identical-twin similarities are probably due to coincidence, such as the Jim twins marrying women with the same first names, others are probably genetically influenced.

So does this mean that there’s a gene for getting married five times or wearing seven rings? Not exactly. Although some physical characteristics and diseases are influenced by a single gene, complex psychological characteristics, such as your personality, are influenced by a large number of genes acting in combination (Caspi & others, 2005; Marcus, 2004). Unlike fraternal twins and regular siblings, identical twins share the same specific configuration of interacting genes. Lykken and his colleagues suggest that many complex psychological traits, including the strikingly similar idiosyncrasies of identical twins, may result from a unique configuration of interacting genes.

Lykken and his colleagues call certain traits emergenic traits because they appear (or emerge) only out of a unique configuration of many interacting genes. Although they are genetically influenced, emergenic traits do not run in families. To illustrate the idea of emergenic traits, consider the couple of average intelligence who give birth to an extraordinarily gifted child. By all predictions, this couple’s offspring should have normal, average intelligence. But because of the unique configuration of the child’s genes acting in combination, extraordinary giftedness emerges (Lykken, 2006; Lykken & others, 1992).

David Lykken compares emergenic traits to a winning poker hand. All the members of the family are drawing from the same “deck,” or pool of genes. But one member may come up with the special configuration of cards that produces a royal flush—the unique combination of genes that produces a Shakespeare, an Einstein, or a Beethoven. History is filled with cases of people with exceptional talents and abilities in varied fields who grew up in average families.

Finally, it’s important to point out that there were many differences, as well as similarities, between the identical twins in the Minnesota study. For example, one twin was prone to depression, while the other was not; one twin was an alcoholic, while the other did not drink. So, even with identical twins, it must be remembered that personality is only partly determined by genetics.

Genes confer dispositions, not destinies.

—Danielle Dick & Richard Rose (2002)

So is personality completely determined by genetics? Not at all. As behavioral geneticists Robert Plomin and Essi Colledge (2001) explain, “Individual differences in complex psychological traits are due at least as much to environmental influences as they are to genetic influences. Behavioral genetics research provides the best available evidence for the importance of the environment.” In other words, the influence of environmental factors on personality traits is at least equal to the influence of genetic factors (Rowe, 2003). Some additional evidence that underscores this point is that identical twins are most alike in early life. As the twins grow up, leave home, and encounter different experiences and environments, their personalities become more different (Bouchard, 2004; McCartney & others, 1990).

Evaluating the Trait Perspective on Personality

Although psychologists continue to disagree on how many basic traits exist, they do generally agree that people can be described and compared in terms of basic personality traits. But like the other personality theories, the trait approach has its weaknesses (Block, 1995).

One criticism is that trait theories don’t really explain human personality (Epstein, 2010; Pervin, 1994). Instead, they simply label general predispositions to behave in a certain way. Second, trait theorists don’t attempt to explain how or why individual differences develop (Boyle, 2008). After all, saying that trait differences are due partly to genetics and partly to environmental influences isn’t saying much.

A third criticism is that trait approaches generally fail to address other important personality issues, such as the basic motives that drive human personality, the role of unconscious mental processes, how beliefs about the self influence personality, or how psychological change and growth occur (Block, 2010; McAdams & Walden, 2010). Conspicuously absent are the grand conclusions about the essence of human nature that characterize the psychoanalytic and humanistic theories. So, although trait theories are useful in describing individual differences and predicting behavior, there are limitations to their usefulness.

As you’ve seen, each of the major perspectives on personality has contributed to our understanding of human personality. The four perspectives are summarized in TABLE 11.5.

The Major Personality Perspectives

| Perspective | Key Theorists | Key Themes and Ideas |

|---|---|---|

| Psychoanalytic | Sigmund Freud | Influence of unconscious psychological processes; importance of sexual and aggressive instincts; lasting effects of early childhood experiences |

| Carl Jung | The collective unconscious, archetypes, and psychological wholeness | |

| Karen Horney | Importance of parent– |

|

| Alfred Adler | Striving for superiority, compensating for feelings of inferiority | |

| Humanistic | Carl Rogers | Emphasis on the self-concept, psychological growth, free will, and inherent goodness |

| Abraham Maslow | Behavior as motivated by hierarchy of needs and striving for self-actualization | |

| Social Cognitive | Albert Bandura | Reciprocal interaction of behavioral, cognitive, and environmental factors; emphasis on conscious thoughts, self-efficacy beliefs, self-regulation, and goal setting |

| Trait | Raymond Cattell | Emphasis on measuring and describing individual differences; 16 source traits of personality |

| Hans Eysenck | Three basic dimensions of personality: introversion– |

|

| Robert McCrae, Paul Costa, Jr. | Five-factor model, five basic dimensions of personality: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness |

Our discussion of personality would not be complete without a description of how personality is formally evaluated and measured. In the next section, we’ll briefly survey the tests that are used in personality assessment.

Test your understanding of Different Perspectives on Personality with

.

.