TO THE INSTRUCTOR

Welcome to the seventh edition of Psychology!

We’ve been gratified by the enthusiastic response to the six previous editions of Psychology. We’ve especially enjoyed the e-mails and letters we’ve received from students who felt that our book was speaking directly to them. Students and faculty alike have told us how much they appreciated Psychology’s distinctive voice, its inviting learning environment, the engaging writing style, and the clarity of its explanations—qualities we’ve maintained in the seventh edition.

But as you’ll quickly see, this new edition is marked by exciting new changes: a fresh new look, a stronger and more explicit emphasis on scientific literacy, a digital experience that is more tightly integrated for both students and instructors, and—most important—a new co-author! More about these features later.

Before we wrote the first word of the first edition, we had a clear vision for this book: combine the scientific authority of psychology with a narrative that engages students and relates to their lives. Drawing from decades (yes, it really has been decades) of teaching experience, we’ve written a book that weaves cutting-edge psychological science with real-life stories that draw students of all kinds into the narrative.

While there is much that is new, this edition of Psychology reflects our continued commitment to the goals that have guided us as teachers and authors. Once again, we invite you to explore every page of the new edition of Psychology, so you can see firsthand how we:

Communicate both the scientific rigor and the personal relevance of psychology

Encourage and model critical and scientific thinking

Show how classic psychological studies help set the stage for today’s research

Clearly explain psychological concepts and the relationships among them

Present controversial topics in an impartial and evenhanded fashion

Expand students’ awareness of cultural and gender influences

Create a student-friendly, personal learning environment

Provide an effective pedagogical system that helps students develop more effective learning strategies

What’s New in the Seventh Edition

Big Changes!

We began the revision process with the thoughtful recommendations and feedback we received from hundreds of faculty using the text, from reviewers, from colleagues, and from students. We also had face-to-face dialogues with our own students as well as groups of students across the country. As you’ll quickly see, the seventh edition marks a major step in the evolution of Psychology. We’ll begin by summarizing the biggest changes to this edition—starting with the most important: a new co-author!

Introducing … Susan Nolan

We are very excited and pleased to introduce Susan A. Nolan as our new co-author. When the time came to search for a new collaborator, we looked for someone who was an accomplished researcher, a dedicated teacher, and an engaging writer with a passion for communicating psychological science to a broad audience. A commitment to gender equality and cultural sensitivity, and, of course, a good sense of humor were also requirements, as were energy and enthusiasm. We found that rare individual in Susan A. Nolan, Professor of Psychology at Seton Hall University.

Susan made several valuable contributions to the sixth edition of Psychology, and the success of that collaboration prompted our decision to make her a full co-author with this new edition. Reflecting her expertise in clinical and social psychology, and her background in gender, culture, and diversity studies, Susan revised Chapter 10, Gender and Sexuality; Chapter 12, Social Psychology; Chapter 14, Psychological Disorders; and Chapter 15, Therapies. And, she participated fully in our text-wide decisions about design, photographs, art, and content. Beyond the text, she’s been fully involved in the development of some exciting new digital resources for the new edition. But more on that below.

New Emphasis on Scientific Literacy

As psychology instructors well know, students come to psychology with many preconceived ideas, some absorbed from popular culture, about the human mind and behavior. These notions are often inaccurate. Complicating matters is the fact that for many students, introductory psychology may be their first college-level science course—meaning that students sometimes have only the vaguest notion of the nature of scientific methodology and evidence. Thus, one important goal for introductory psychology is to teach students how to distinguish fact from opinion, and research-based, empirical findings from something heard from friends or encountered on the Internet.

The importance of this objective is reinforced by the 2013 revision of the APA Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major. Scientific Literacy and Critical Thinking is identified as one of its five key goals. Psychology educators agree that the skills students learn in psychology can be as important as the content. Scientific literacy and critical thinking skills can help students in a variety of careers, a variety of majors, and can help ensure that students become critical consumers of scientific information in the world around them.

Since the first edition, a hallmark of Psychology and its sister publication, Discovering Psychology, has always been their emphasis on critical and scientific thinking. Psychology was the first introductory psychology textbook to formally discuss and define pseudosciences and to distinguish pseudoscience from science. Our trademark Science Versus Pseudoscience boxes, which take a critical look at the evidence for and against phenomena as diverse as graphology, educational videos for infants, and ESP research have proved very popular among instructors and students alike.

In this new edition, we decided to make the scientific literacy theme even more explicit. These new features are described below.

New Think Like a Scientist Model and Digital Feature

To help students learn to develop their scientific thinking skills and become critical consumers of information, a unique feature of the seventh edition is a set of Think Like a Scientist digital activities. Developed for Psychology by co-authors Susan Nolan and Sandy Hockenbury, each digital activity provides students with the opportunity to apply their critical thinking and scientific thinking skills. These active learning exercises combine video, audio, text, and assessment to help students hone and master scientific literacy skills they will use well beyond the introductory course. In these activities, students will be invited to critically explore questions they encounter in everyday life, such as “Can you learn to tell when someone is lying?” and “Are some people ‘left-brained’ and some people ‘right-brained’?”

These activities employ a simple four-step model introduced in the new Critical Thinking box “How to Think Like a Scientist” in Chapter 1. These four steps include:

Identify the Claim

Evaluate the Evidence

Consider Alternative Explanations

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

The Think Like a Scientist digital activities are designed to teach and develop a skill set that will persist long after the final exam grades are recorded. We hope to develop a set of transferable skills that can be applied to analyzing dubious claims in any subject area—from advertisements to politics. We think students will enjoy completing these activities—and instructors will value them. The seventh edition of Psychology includes the following Think Like a Scientist digital activities:

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can you be classified as right-brained or left-brained? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about The Right Brain Versus the Left Brain.

Contagious Online Emotions (Chapter 1)

The Right Brain Versus the Left Brain (Chapter 2)

ESP (Chapter 3)

Multi-Tasking (Chapter 4)

Positive and Negative Reinforcement (Chapter 5)

Eyewitness Testimony (Chapter 6)

Brain Exercises (Chapter 7)

Lie Detection (Chapter 8)

Learning Environments (Chapter 9)

Gender Stereotypes (Chapter 10)

Employment-Related Personality Tests (Chapter 11)

Online Dating (Chapter 12)

Coping with Stress (Chapter 13)

Tracking Mental Illness Online (Chapter 14)

Ketamine (Chapter 15)

New Myth or Science? Feature

Students often come to the introductory psychology course with misperceptions about psychological science. Our new Myth or Science? feature will help dispel some of these popular but erroneous beliefs.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that multi-tasking is an efficient way to get things done?

Each chapter begins with a list of “Is It True?” questions that reflect popular myths about human behavior. These statements were tested with market research to see what percentage of students actually endorsed them. In some cases, agreement reached astonishing levels. For example, in one survey, more than 85% of students agreed that “the right brain is creative and intuitive, and the left brain is analytic and logical” and that “some people are left-brained and some people are right-brained.” More than 70% of students agreed that “flashbulb memories are more accurate than normal memories” and that “most psychologists agree with Freud’s personality theory.” And, more than 90% of surveyed students agreed that “dying people go through five predictable stages.” Even frequently debunked statements like “you only use 10% of your brain” received a high rate of agreement.

After being posed at the beginning of the chapter, each question is answered in the body of the chapter. A margin note signals the student to find the explanation and indicates whether the statement is “myth” or “science.”

New Data Presentation Program

Our new co-author Susan Nolan brought her expertise in data analysis and presentation to the fully revised graphic art program. We’ve redesigned our graphs more closely in line with graphing expert Edward Tufte’s (1997) guidelines for clear, consistent data visualizations. Graphs are simpler than in previous editions. Most now use fewer colors per graph, and fewer and lighter background gridlines, to allow the representations of data—the bars, for example—to emerge as the most important element. We have used plain bar graphs whenever possible, starting the y axes at 0. When the variable is a percentage, we extended the y axis to 100% whenever possible. We hope that the simpler, more streamlined graphs will allow students to more readily “see” and accurately interpret data.

New Research Methods Section in Chapter 1

Introductory chapters have a reputation for being dry and boring. Instructors, though, know that there are few alternatives: history and methods need to be taught before plunging into content-heavy chapters. For this edition, the section on research methods has been completely rewritten to highlight psychological science on the topic of student success. New research examples—such as the impact of social media on well-being, the effect of multi-tasking on studying, the testing effect, and measures of student well-being—were chosen for their relevance to today’s students’ lives.

The new end-of-chapter application, Psych for Your Life: Successful Study Techniques, provides six research-based strategies to maximize student success. In other words, rather than waiting for the Learning or Memory chapters to introduce study skills tips, we’ve incorporated these important findings right into Chapter 1—and used them to demonstrate the relevance of psychological research in students’ everyday lives and academic success. Along with demonstrating to students how psychological research can be used to improve everyday life, the new application gives them a solid foundation of research-based study skills and tips.

All-New Digitally Integrated Package

Today’s college students are digital natives. They are accustomed to going online to seek answers and to connect with friends, fellow students, and their instructors. Past editions of Psychology provided a wealth of online resources for students, but the new seventh edition marks a step to a new level of digital integration with LaunchPad.

LaunchPad, our new course space, combines an interactive e-Book with high-quality multimedia content and ready-made assessment options, including LearningCurve adaptive quizzing. Pre-built, curated units are easy to assign or adapt with your own material, such as readings, videos, quizzes, discussion groups, and more. LaunchPad also provides access to a gradebook that offers a window into your students’ performance—either individually or as a whole. While a streamlined interface helps students focus on what’s due next, social commenting tools let them engage, make connections, and learn from each other. Use LaunchPad on its own or integrate it with your school’s learning management system so your class is always on the same page.

The Latest Psychological Science

As was the case with previous editions, we have extensively updated every chapter with the latest research. We have pored over dozens of journals and clicked through thousands of Web sites to learn about the latest in psychological science. As a result, this new edition features hundreds of new references. Just to highlight a few additions, the seventh edition includes brand-new sections on scientific thinking and factors contributing to college success (Chapter 1); traumatic brain injury and concussion (Chapter 2); bilingualism (Chapter 7); evolutionary and interactionist theories of gender development, and transgender identity in multiple cultures (Chapter 10); aggression and violence (Chapter 12); and a critical look at the effectiveness of antidepressants compared to placebo treatments (Chapter 15). And, there are four new prologues (Chapters 1 , 8 , 10 , and 14).

In addition, we have significantly updated coverage of neuroscience and expanded our coverage of culture, gender, and diversity throughout the text. DSM-5 terminology and criteria have been fully integrated into the new edition.

As of our last count, there are over 1,000 new references in the seventh edition of Psychology, more than half of which are from 2012 or later. These new citations reflect the many new and updated topics and discussions in the seventh edition of Psychology. From the effects of social media and multi-tasking on student success to the latest discoveries about oxytocin, aggression, women in STEM fields, stress and telomeres, or the effectiveness of meditation in controlling pain and improving attention, our goal is to present students with interesting, clear explanations of psychological science. Later in this preface, you’ll find a list of the updates by chapter.

New Design, New Photos

Created with today’s media-savvy students in mind, the clean, modern, new look of Psychology showcases the book’s cutting-edge content and student-friendly style. Carefully chosen photographs—more than 60 percent of them new—apply psychological concepts and research to real-world situations. Accompanied by information-rich captions that expand upon the text, vivid and diverse photographs help make psychology concepts come alive, demonstrating psychology’s relevance to today’s students.

Connections to the American Psychological Association’s Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major

The American Psychological Association has developed the APA Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major: Version 2.0 to provide “optimal expectations for performance” by undergraduate psychology students. The APA Guidelines include five broad goals, which are summarized below. This table shows how Hockenbury, Nolan, and Hock-enbury’s Psychology, Seventh Edition, helps instructors and students achieve these goals.

| Goal 1: Knowledge Base in Psychology |

|---|

| APA Learning Objectives: |

| 1.1—Describe key concepts, principles, and overarching themes in Psychology |

|

| 1.2—Develop a working knowledge of psychology’s content domains |

|

| 1.3—Describe applications of psychology |

|

| Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking |

| APA Learning Objectives: |

| 2.1—Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena |

|

| 2.2—Demonstrate psychology information literacy |

|

| 2.3—Engage in innovative and integrative thinking and problem solving |

|

| 2.4—Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research |

|

| 2.5—Incorporate sociocultural factors in scientific inquiry |

|

| Goal 3: Ethical and Social Responsibility in a Diverse World |

| APA Learning Objectives: |

| 3.1—Apply ethical standards to evaluate psychological science and practice |

|

| 3.2—Build and enhance interpersonal relationships |

|

| 3.3—Adopt values that build community at local, national, and global levels |

|

| Goal 4: Communication |

| APA Learning Objectives: |

| 4.1—Demonstrate effective writing for different purposes |

|

| 4.2—Exhibit effective presentation skills for different purposes |

|

| 4.3—Interact effectively with others |

|

| Goal 5: Professional Development |

| APA Learning Objectives: |

| 5.1—Apply psychological content and skills to career goals |

|

| 5.2—Exhibit self-efficacy and self-regulation |

|

| 5.3—Refine project-management skills |

|

| 5.4—Enhance teamwork capacity |

|

Major Chapter Revisions

As you page through our new edition, you will encounter new examples, boxes, photos, and illustrations in every chapter. Below are highlights of some of the most significant changes:

CHAPTER 1, INTRODUCTION AND RESEARCH METHODS

New Prologue, “The First Exam,” focusing on test experiences and student study strategies

New chapter introduction incorporating psychology’s goals

New photo example of the topics that psychologists study

New photo examples of the biological perspective and cross-cultural psychology

New summary table and graphs showing specialty areas and employment settings for psychologists

New student-focused research examples and photo illustrations of concepts in research methods, including forming a hypothesis, operational definitions, statistical significance, and meta-analysis

New example of how to read a journal reference

Revised and updated Science Versus Pseudoscience box

New example of naturalistic observation

New student-focused example of survey research using the National Survey of Student Engagement, including results comparing study habits of different majors

New section on correlational studies, using research on student study behaviors and strategies to illustrate positive and negative correlations

New explanation of experimental methods, using an experiment on the testing effect to illustrate the key terms and important concepts of experimental design

New Critical Thinking box, “How to Think Like a Scientist,” introducing a four-step model for scientific thinking that students can apply to any claim or belief

Discussion of use of animals in research moved into main text

Entirely new “Psych for Your Life” application that provides six research-based study techniques to enhance student success. Along with providing helpful information right at the beginning of the semester, the application demonstrates the value and relevance of psychological research.

CHAPTER 2, NEUROSCIENCE AND BEHAVIOR

Added information in Figure 2.1 about the structure of sensory neurons

New photo of neuron

Streamlined discussions of communication within the neuron, the action potential, and communication between neurons

Discussion of important neurotransmitters expanded to include glutamate, now a boldfaced key term

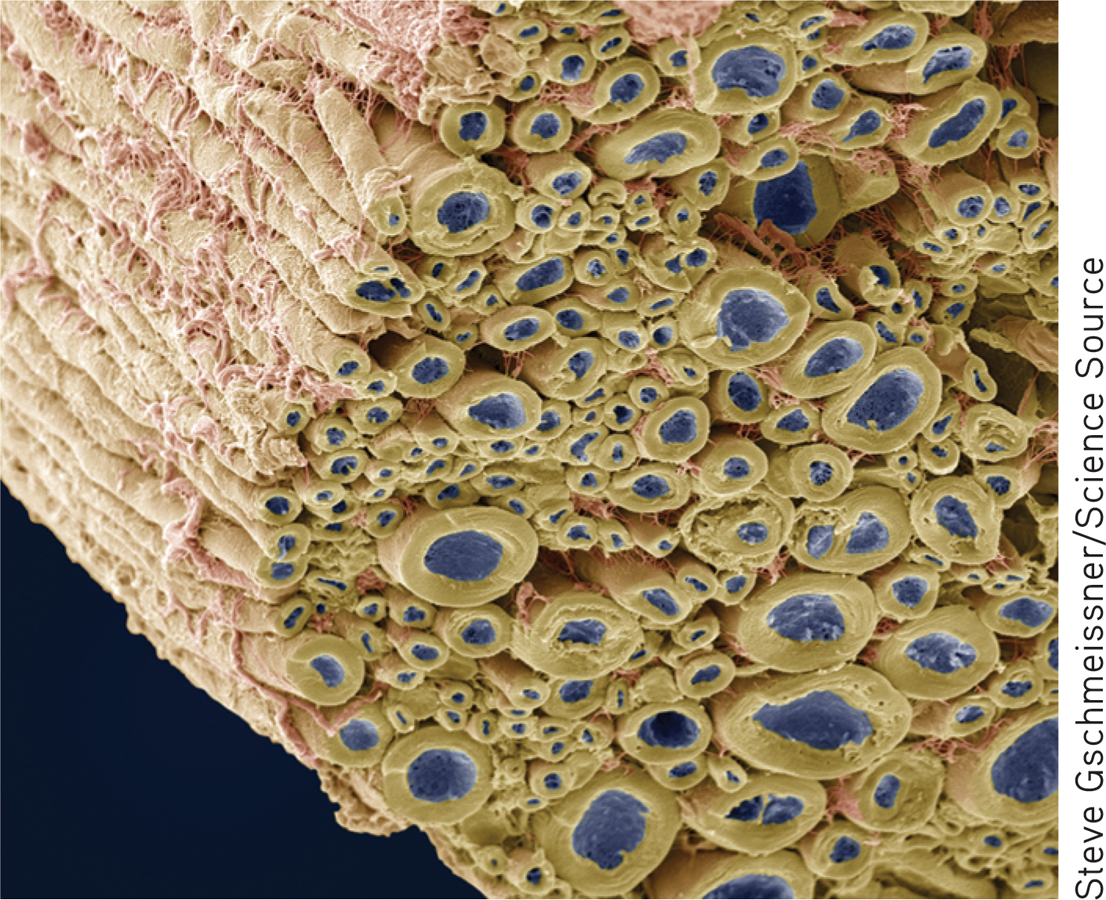

Nerves and Neurons Are Not the Same A cross section of a peripheral nerve is shown in this electron micrograph. The nerve is composed of bundles of axons (blue) wrapped in the myelin sheath (yellow). In the peripheral nervous system, myelin is formed by a type of glial cell called Schwann cells, shown here as a pinkish coating around the axons.

Nerves and Neurons Are Not the Same A cross section of a peripheral nerve is shown in this electron micrograph. The nerve is composed of bundles of axons (blue) wrapped in the myelin sheath (yellow). In the peripheral nervous system, myelin is formed by a type of glial cell called Schwann cells, shown here as a pinkish coating around the axons.Endorphins discussion integrated into main text and illustrated with photo rather than discussed in a separate Focus on Neuroscience box

New photo examples of botox, dopamine, and Parkinson’s Disease

New In Focus box, “Traumatic Brain Injury: From Concussions to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy,” exploring the causes and long-term implications of these injuries, with special reference to veterans and athletes

Expanded discussion of oxytocin, now a boldfaced key term, with coverage of research on its diverse effects on social motivation and behavior

Coverage of “The 10% Myth” now integrated into text

Updated and streamlined discussion of plasticity and neurogenesis, now integrated into a single section and including 2013 research on carbon-14 dating of new neuron

New photo and updated research on Phineas Gage’s injury

Expanded and updated coverage of the amygdala and its functions

Updated and simplified Critical Thinking box, “‘His’ and ‘Her’ Brains?”

Revised and updated Science Versus Pseudoscience box, “Brain Myths,” includes new research on brain lateralization

Updated research and new photo in Psych for Your Life: Maximizing Your Brain’s Potential

CHAPTER 3, SENSATION AND PERCEPTION

Streamlined and updated box on subliminal perception

New photo example of color blindness

Revised figure clarifiing human auditory structures and process of hearing

Added discussion of cochlear implants, with photo illustration

Added information about the dangers of noise exposure in everyday life and from personal music players

New example of how frogs without outer ears detect sound

New 2014 cross-cultural research on the language of smell in non-Western groups

Revised In Focus box “Do Pheromones Influence Human Behavior?” that includes new 2013 and 2014 research on human chemosignals

New photo illustrating top-down subjective preconceptions on judgments of taste/quality

New 2013 cross-cultural research on effects of ethnicity and culture on pain perception, illustrated with photo

New drawings illustrating the Müller-Lyer illusion and the Shepard Tables illusion

Dramatic new photos illustrating figure-ground camouflage in nature, Gestalt principles of organization, and the moon illusion

Revised and updated Psych for Your Life, including new research on the effectiveness of acupuncture in pain control

CHAPTER 4, CONSCIOUSNESS AND ITS VARIATIONS

Streamlined discussion of circadian rhythms and the suprachiasmatic nucleus

Updated research on multi-tasking, including 2014 data on cell phone usage contributing to motor vehicle accidents

New research on the effects of artificial light, including computer and tablet screens, on circadian rhythms

Streamlined In Focus box, “What You Really Want to Know About Sleep”

Revised section, “Why Do We Sleep?” includes new research on sleep and memory formation, the effects of sleep deprivation and sleep restriction, and the link between sleep restriction and weight gain

Updated, reorganized, and streamlined discussion of Dreams and Mental Activity During Sleep

Condensed Focus on Neuroscience, “The Dreaming Brain”

Streamlined coverage of sleep disorders and hypnosis

Updated and condensed Critical Thinking box on theories of hypnosis

“Drug abuse” has been changed to “Substance Abuse Disorder” and definition has been revised to conform with DSM-5 language; requirement that legal problems be present has been dropped, and requirement that craving be present has been added

Updated 2013 data noting that most overdose deaths are now due to legal prescription drugs rather than illegal drugs

New photos of Amy Winehouse, illustrating the dangers of alcohol abuse; Cory Monteith, illustrating the dangers of depressant drugs; and Whitney Houston, illustrating the danger of cocaine use

The term opiates replaced with the more accurate term opioids

Added 2014 data on the deaths from the accidental overdose of prescription opioids

Updated 2014 research on the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs

Updated information on the legal use of medical marijuana, including 2014 research on data showing fewer opioid overdose deaths in states with legal access to medical marijuana for pain treatment

Revised and updated coverage of the effects of MDMA (“Ecstasy”)

New photo examples of psychoactive drug use around the world, cross-cultural examples of legal stimulant use, rave culture, and peyote-inspired visions

CHAPTER 5, LEARNING

New photo examples of learning, Ivan Pavlov, primary and conditioned reinforcers, using reinforcement in the classroom, media response to Skinner’s work, applications of operant conditioning, and observational learning

Streamlined discussion of John B. Watson and introduction to behaviorism

New contemporary photo example of classical conditioning in advertising

Streamlined coverage of the “Little Albert” story

2014 research suggesting a second identification for the infant in the famous “Little Albert” study, Albert Barger Martin

Condensed and simplified presentation of Robert Rescorla’s classic research

Revised section on taste aversions, including new example of using conditioned taste aversions to protect the endangered northern quoll in Australia

Replaced reinforcement example of hitting a vending machine with pushing the coin-return lever

In text and tables, replaced the terms “punishment by application” and “punishment by removal” with “positive punishment” and “negative punishment”

Revised graphs showing schedules of reinforcement and response patterns

New photo example showing how behavior modification is used to train helper animals

New historical photo of Keller and Marian Breland

Updated biographical information about Martin E. P. Seligman

Streamlined and updated Focus on Neuroscience, “Mirror Neurons: Imitation in the Brain”

New 2013 research example of observational learning in animals

New 2014 research on media effects on behavior, identifying a correlational link between a decrease in teen birth rates and viewership of an MTV reality series showing the struggles of teenage parents

New photo example of a Kenyan “education-entertainment” program based on Bandura’s observational learning research

CHAPTER 6, MEMORY

Revised art demonstrating Baddeley’s model of working memory

New tip-of-the-tongue examples

Updated flashbulb memory examples and new photo illustration

Revised graph showing the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve

Updated In Focus box on déjà-vu experiences with 2012 research and new cartoon

New photo examples of the serial position effect, “tip-of-the-fingers” experience, flashbulb memories, eyewitness misidentification, and motivated forgetting

New research showing that pre-existing schemas can distort memories of events within seconds

New 2013 research, conducted by the online magazine Slate, showing how faked news photographs can produce false memories about political events

New photos of Eric Kandel, Aplysia, and David Snowden with an elderly participant in the Nun Study of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

New photos of Suzanne Corkin, Henry Molaison (the famous “H.M.”), and of a virtual model of H.M.’s damaged brain based on new 2014 research

Fully revised Psych for Your Life application, “Ten Steps to Boost Your Memory” and new photo of memory superstar and journalist Josh Foer

CHAPTER 7, THINKING, LANGUAGE, AND INTELLIGENCE

The new term autism spectrum disorder has replaced autism and Asperger’s syndrome in the Prologue and throughout the chapter to conform to the DSM-5 classification

The term intellectual disability has replaced mental retardation in the In Focus box “Neurodiversity: Beyond IQ” to conform to new DSM-5 terminology

Updated research on problem-solving strategies

New extended example of functional fixedness—repurposing plastic bags and bottles into useful objects—illustrated with new photo

Confirmation bias introduced as a boldfaced term

New photo examples of American Sign Language and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences

Entirely new section on bilingualism and its cognitive benefits

Streamlined discussion of the roles of genetics and environment in determining intelligence, and updated research on the Flynn Effect

Updated discussion of stereotype threat

New photo example of creativity: Steve Jobs

CHAPTER 8, MOTIVATION AND EMOTION

New prologue, “One Step, One Breath,” about one of the authors’ experiences as a volunteer trekking through a remote region of the Himalayas

Revised, condensed, and streamlined introduction to motivational theories

New photo examples of sensation seekers, achievement motivation, emotion, arousal and intense emotion, the facial feedback hypothesis, and appraisal and emotion

The Many Functions of Emotion Two friends share news, smiles, and laughter as they patiently wait their turns at the medical clinic in an isolated village in Tsum Valley, Nepal. Emotions play an important role in relationships and social communication.

The Many Functions of Emotion Two friends share news, smiles, and laughter as they patiently wait their turns at the medical clinic in an isolated village in Tsum Valley, Nepal. Emotions play an important role in relationships and social communication.Condensed, simplified, and updated section on hunger and eating

New examples of how culture shapes food choices

New information about body mass index and alternative measures of obesity

New data on the role that globalization plays in the increase in obesity in developing countries worldwide

Updated Critical Thinking box “Has Evolution Programmed Us to Overeat?” including 2014 research on stigma associated with obesity

2014 research on the decrease in physical activity levels in the United States over the past decade

Revised introduction to Psychological Needs as Motivators section

New example of achievement motivation

Updated research on self-determination theory

Updated research on the functions of emotion and emotional intelligence

Streamlined and updated discussion of the subjective experience of emotion and the neuroscience of emotion, including new photo example

New figure based on 2014 cross-cultural research on the association of different emotions with specific physical sensations

New photo of William James

Updated research on cognitive theories of emotion

CHAPTER 9, LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT

Revised introduction, with new discussion of longitudinal and cross-sectional research designs; longitudinal design and cross-sectional design are new key terms

New photo of X and Y chromosomes

Expanded and updated discussion of research on the epigenetic effects of early life stress in human subjects

New photo and discussion of Harry Harlow’s classic “contact comfort” research and its role in attachment

New photos of Mary Ainsworth and Erik Erikson

Streamlined section on language development

New photo examples of cognitive development and Piagetian stages

New material on adolescent social development explores peer influence and romantic and sexual relationships

Expanded discussion of moral development, including new photo example

Entirely new section, “Emerging Adulthood,” introduces the period from the late teens until the mid- to late-twenties as a distinct stage of the lifespan

New discussion of the myth of the mid-life crisis

Thoroughly revised section on social development in adulthood

Updated statistics on U.S. households, including changes in family structure

New discussion of the effect of parenthood on marital satisfaction, including research about the so-called empty-nest syndrome and the new phenomenon of “boomerang kids”

CHAPTER 10, GENDER AND SEXUALITY

Challenging Expectations What makes weight lifting a “male” activity? Evstyukhina Nadezda, a world champion weight lifter from Russia, engages in athletic pursuits that many might not expect for a woman. Are biological constraints a factor here?

Challenging Expectations What makes weight lifting a “male” activity? Evstyukhina Nadezda, a world champion weight lifter from Russia, engages in athletic pursuits that many might not expect for a woman. Are biological constraints a factor here?New prologue about a young transgender man, Jamie, growing up in a small town in rural New York

Revised introduction

Fully revised and updated discussion of gender differences in emotionality, now placed within the main text

Entirely new discussion of leadership and gender

Updated discussion of gender differences in math and science performance, including 2013 cross-cultural research

New Critical Thinking box, “Gender Differences: Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Fields”

Fully revised section on theories of gender-role development now includes evolutionary and interactionist theories

New photo examples of gender-stereotyped toys

Variations in gender identity now covered within the main text, with expanded coverage of transgender development

New Culture and Human Behavior box, “The Outward Display of Gender”

New photo of Masters and Johnson

Evolution and mate preferences now covered within the main text

Updated research in Focus on Neuroscience, “Romantic Love and the Brain”

Updated coverage of sexual attitudes

Updated and expanded In Focus box, “Hooking Up on Campus”

New photo examples of gender-role stereotypes, color-coding and gender, transgender individuals, famous gay couples, sexual fantasies, primate sexual behavior

Revised section on sexual disorders and problems, incorporating DSM-5 updates and terminology

New figures and information on rates of HIV infections in the United States and globally

Establishing the Superego As children, we learn many rules and values from parents and other authorities. The internalization of such values is what Freud called the superego—the inner voice that is our conscience. When we fail to live up to its moral ideals, the superego imposes feelings of guilt, shame, and inferiority.

Establishing the Superego As children, we learn many rules and values from parents and other authorities. The internalization of such values is what Freud called the superego—the inner voice that is our conscience. When we fail to live up to its moral ideals, the superego imposes feelings of guilt, shame, and inferiority.Revised Psych for Your Life application, “Reducing Conflict in Intimate Relationships”

CHAPTER 11, PERSONALITY

New photos of Carl Jung and Carl Rogers

Updated discussion of Alfred Adler’s theory of personality

Many new photo examples, including mandalas in diverse cultures, Freud’s influence on popular culture, unconditional positive regard, the TAT, and self-efficacy

New cross-cultural photo illustration for Critical Thinking box, “Freud Versus Rogers on Human Nature”

Updated discussion of the humanistic perspective

Streamlined discussion of self-efficacy with new student-centered example

New cross-cultural research on the universality of the five-factor model of personality

CHAPTER 12, SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

Discussion of person perception updated with new research on the role of person perception in social media

Condensed introduction to attribution

New photo example of blaming the victim—the story of Elizabeth Smart

Revised discussion of cognitive dissonance, with new examples and research on cognitive dissonance in preschoolers and capuchin monkeys

Updated discussion of physical attractiveness

Updated In Focus box, “Interpersonal Attraction and Liking”

New cross-cultural research on in-group bias

Expanded and updated discussion of prejudice, incorporating new 2013 research and neuroscience evidence

New discussion of contemporary replication of Milgram’s obedience study

New information on conditions that undermine obedience

Condensed Critical Thinking box, “Abuse at Abu Ghraib”

New section, “Altruism and Aggression,” includes expanded coverage of Latané and Darley’s research on bystander intervention, additional factors that increase the likelihood of bystanders helping, and entirely new section on aggression

New figures on aggression and the brain, and the influence of sociocultural factors on aggression

New photos and captions provide contemporary examples of the self-serving bias, the effect of attitudes on behavior, research linking prejudice and negative emotion, destructive obedience of authority, blaming the victim bias, road rage, social loafing, and deindividuation

CHAPTER 13, STRESS, HEALTH, AND COPING

New photo examples of stress and appraisal, major life events and stress, daily hassles, explanatory style, Type A behavior pattern, providing social support, the role of personal control in the response to stress, the benefits of social support

Updated discussion of posttraumatic stress disorder to incorporate DSM-5 criteria

“Stress, Chromosomes, and Aging” updated with 2014 research

New prologue example in the In Focus box, “Providing Effective Social Support”

New cross-cultural photo examples of major life events, daily hassles and stress, daily hassles, the benefits of social support, and problem-focused coping

CHAPTER 14, PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

New Prologue about the psychotic break and successful life of a woman with schizophrenia—Elyn Saks

Expanded coverage of the DSM-5, presenting a history of the manual, including critiques

New coverage of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases

Critical Thinking box updated with new research on violence and mental illness

Revised table displaying prevalence data for the most common psychological disorders

Updated cross-cultural research on prevalence of psychological disorders and treatment rates in developing countries

Revised Table of Key Diagnostic Categories, incorporating DSM-5 terminology and criteria

Revised introduction to “Anxiety Disorders,” incorporating DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and OCD

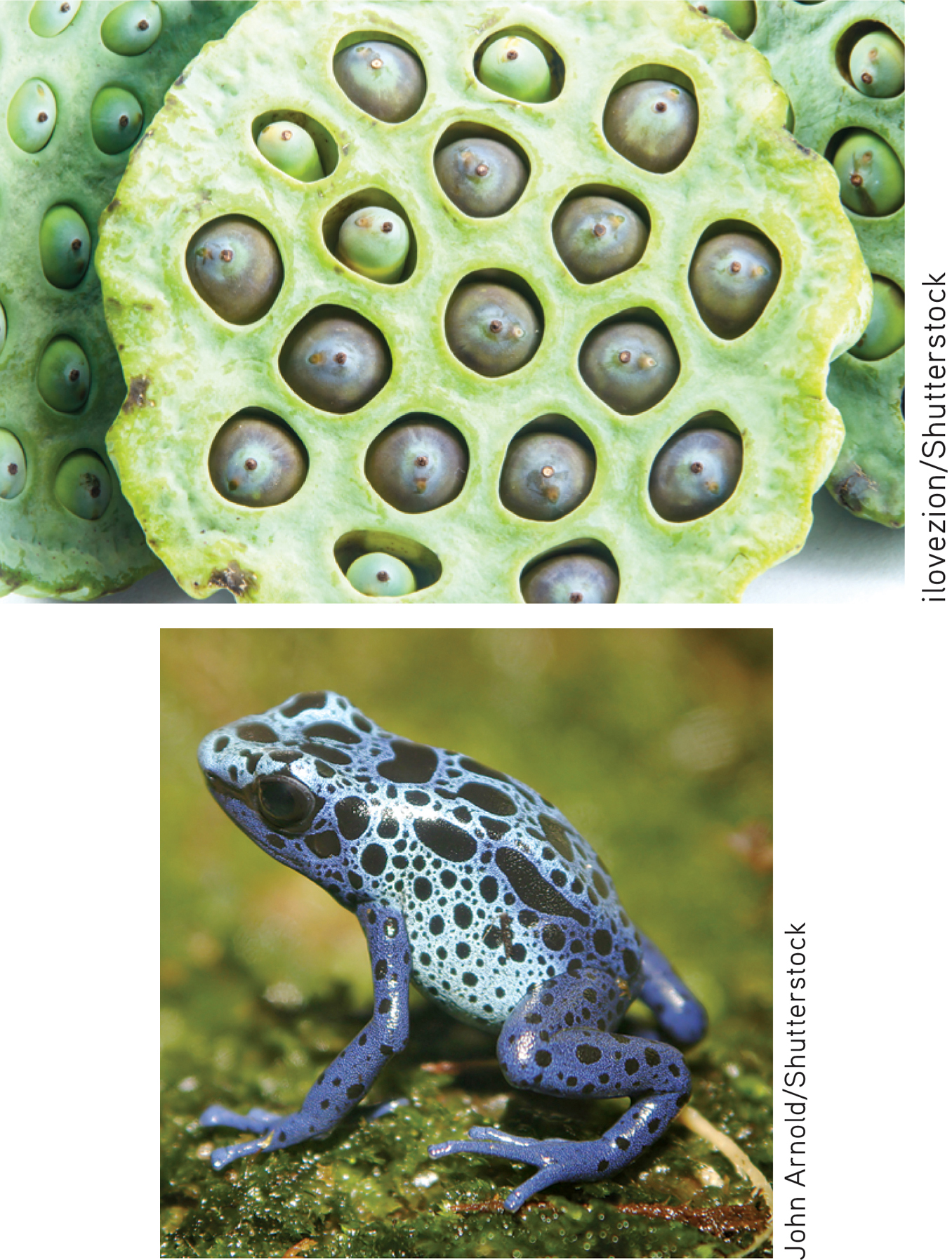

An Evolutionary Fear of Holes Some people are afraid of a certain pattern of holes like those you might see in a chocolate bar, in soap bubbles, or on a lotus seed head like the one shown here. This condition is called trypophobia. Researchers Geoff Cole and Arnold Wilkins (2013) found striking similarities between the visual pattern that triggers fear in trypophobics and the markings on poisonous animals, like certain snakes or the poison dart frog shown here. They speculate that an ability to quickly notice a poisonous creature gave people an evolutionary advantage, even if it sometimes led them to fear harmless objects.

An Evolutionary Fear of Holes Some people are afraid of a certain pattern of holes like those you might see in a chocolate bar, in soap bubbles, or on a lotus seed head like the one shown here. This condition is called trypophobia. Researchers Geoff Cole and Arnold Wilkins (2013) found striking similarities between the visual pattern that triggers fear in trypophobics and the markings on poisonous animals, like certain snakes or the poison dart frog shown here. They speculate that an ability to quickly notice a poisonous creature gave people an evolutionary advantage, even if it sometimes led them to fear harmless objects.New evolutionary discussion of phobias

New phobia example—Oprah Winfrey’s fear of chewing gum

Updated discussion of posttraumatic stress disorder to incorporate DSM-5 criteria

Section on social phobia relabeled Social Anxiety Disorder to conform to DSM-5 terminology, and criteria updated with new research, including cross-cultural research

Reorganized sections on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

New cross-cultural research on posttraumatic stress disorder in children living in the Middle East

New research on how PTSD symptoms can be triggered by reports in the news media and by events unrelated to the original trauma

Updated research on the role played by pre-existing vulnerability in the development of PTSD

Section on “Mood Disorders” retitled as “Disordered Moods and Emotions: Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder” to conform to new DSM-5 terminology

New discussion of DSM-5’s controversial removal of “the bereavement exclusion” that excluded symptoms caused by bereavement as criteria for depression

New photo example of major depressive disorder, featuring J. K. Rowling and her fictional “dementors”

Updated longitudinal research on the prevalence and recurrence of major depressive disorder over the lifespan

Section on major depressive disorder updated with 2014 research

New research on the roles of stress in major depressive disorder

New example to introduce bipolar disorder

Updated 2013 and 2014 research on the causes of depressive and bipolar disorders

Updated Critical Thinking box “Does Smoking Cause Depression and Other Psychological Disorders?” includes revised graph

Eating Disorders section expanded and updated to incorporate DSM-5 terminology and criteria, including a new section on the newly described disorder “binge-eating disorder”

New Culture and Human Behavior box, “Culture-Bound Syndromes”

Updated discussion of personality disorders introduces second approach to classification

New discussion of the differences among psychopath, sociopath, and antisocial personality disorder, with new photo examples

Updated research on borderline personality disorder

Updated 2014 research on the controversy surrounding the authenticity of dissociative identity disorder

Fully revised section on schizophrenia, including new examples, extended coverage of variations of symptoms across cultures, and a cross-cultural look at prevalence

New photo example of the Truman Show delusion as a culturally-specific symptom of schizophrenia

New photo examples of people with depression, bipolar disorder, and, schizophrenia

Psych for Your Life application on understanding and helping to prevent suicide updated with new statistics

CHAPTER 15, THERAPIES

Terminology revised throughout to reflect DSM-5 criteria and diagnostic labels

Streamlined discussion of short-term dynamic therapies

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Tammy, an Alabama woman suffering from depression, receives Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) under the oversight of a nurse. TMS involves stimulating brain regions with magnetic pulses. Tammy is able to receive this noninvasive treatment in her doctor’s office as opposed to in a hospital.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Tammy, an Alabama woman suffering from depression, receives Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) under the oversight of a nurse. TMS involves stimulating brain regions with magnetic pulses. Tammy is able to receive this noninvasive treatment in her doctor’s office as opposed to in a hospital.Updated In Focus box on virtual reality therapy for phobias and posttraumatic stress disorder

Discussion of EMDR and exposure therapies moved into main text, in retitled section “Systematic Desensitization and Exposure Therapies”

Updated 2013 and 2014 research on token economies and contingency management therapies

Discussion of Albert Ellis’s work updated to note “rational-emotive therapy” now renamed “rational-emotive behavior therapy”

Updated coverage of cognitive therapy

Updated section “Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Therapies,” including 2014 research on the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy with clients with schizophrenia to help treat psychotic symptoms

New In Focus box, “Increasing Access: Meeting the Need for Mental Health Care,” introduces the role of paraprofessionals and lay counselors worldwide, plus technology-driven solutions

Expanded and updated discussion, “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy,” includes criteria to evaluate new therapies

Updated research on antipsychotic medications

New Critical Thinking box, “Do Antidepressants Work Better Than Placebos?”, examines the effectiveness of antidepressants

New discussions of the experimental use of MDMA to treat anxiety disorders and PTSD and of ketamine to treat major depressive disorder, incorporating 2014 research

All-new Focus on Neuroscience, “Psychotherapy and the Brain,” presents research comparing the effect of antidepressant and psychotherapy treatment on brain activity in people with major depressive disorder

Updated research on electroconvulsive therapy

Expanded Psych for Your Life application, “What to Expect in Psychotherapy,” including helpful guidance on how to find a qualified psychotherapist

New photo examples of Native American healing, transcranial magnetic stimulation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and technology-based solutions to expanding access to mental health care

APPENDIX B: INDUSTRIAL/ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY

New photo examples of matching job and applicant, differing work styles, and teleworking

Features of Psychology

For all that is new in the seventh edition, we were careful to maintain the unique elements that have been so well received in the previous editions. Every feature and element in our text was carefully developed and serves a specific purpose. From comprehensive surveys, input from reviewers, and our many discussions with faculty and students, we learned what elements people wanted in a text and why they thought those features were important tools that enhanced the learning process. We also surveyed the research literature on text comprehension, student learning, and memory. In the process, we acquired many valuable insights from the work of cognitive and educational psychologists. Described below are the main features of Psychology and a discussion of how these features enhance the learning process.

The Narrative Approach

Associate the new with the old in some natural and telling way, so that the interest, being shed along from point to point, fully suffuses the entire system of objects.… Anecdotes and reminiscences [should] abound in [your] talk; and the shuttle of interest will shoot backward and forward, weaving the new and the old together in a lively and entertaining way.

—William James, Talks to Teachers (1899)

As you’ll quickly discover, our book has a very distinctive voice. From the very first page of this text, the reader comes to know us as people and teachers through carefully selected stories and anecdotes. Some of our friends and relatives have also graciously allowed us to share stories about their lives. The stories are quite varied—some are funny, others are dramatic, and some are deeply personal. All of them are true.

The stories we tell reflect one of the most effective teaching methods: the narrative approach. In addition to engaging the reader, each story serves as a pedagogical springboard to illustrating important concepts and ideas. Every story is used to connect new ideas, terms, and ways of looking at behavior to information with which the student is already familiar.

Prologues

As part of the narrative approach, every chapter begins with a Prologue, a true story about ordinary people with whom most students can readily identify. The Prologue stories range from the experiences of a teenager with Asperger’s Syndrome to people struggling with the aftereffects of a devastating wildfire to the story of a man who regained his sight after decades of blindness. Each Prologue effectively introduces the chapter’s themes and lays the groundwork for explaining why the topics treated by the chapter are important. The Prologue establishes a link between familiar experiences and new information—a key ingredient in facilitating learning. Later in the chapter, we return to the people and stories introduced in the Prologue, further reinforcing the link between familiar experiences and new ways of conceptualizing them.

Logical Organization, Continuity, and Clarity

As you read the chapters in Psychology, you’ll see that each one tells the story of a major topic in a logical way that flows continually from beginning to end. Themes are clearly established in the first pages of the chapter. Throughout the chapter, we come back to those themes as we present subtopics and specific research studies. Chapters are thoughtfully organized so that students can easily see how ideas are connected. The writing is carefully paced to maximize student interest and comprehension. Rather than simply mentioning terms and findings, we explain concepts clearly. And we use concrete analogies and everyday examples, rather than vague or flowery metaphors, to help students grasp abstract concepts and ideas.

Paradoxically, one of the ways that we maintain narrative continuity throughout each chapter is through the use of in-text boxes. The boxes provide an opportunity to explore a particular topic in depth without losing the narrative thread of the chapter. The In Focus boxes do just that—they focus on interesting topics in more depth than the chapter’s organization would allow. These boxes highlight interesting research, answer questions that students commonly ask, or show students how psychological research can be applied in their own lives. The seventh edition of Psychology includes the following In Focus boxes:

Traumatic Brain Injury: From Concussions to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, p. 54

Do Pheromones Influence Human Behavior?, p. 103

What You Really Want to Know About Sleep, p. 141

What You Really Want to Know About Dreams, p. 152

Watson, Classical Conditioning, and Advertising, p. 190

Evolution, Biological Preparedness, and Conditioned Fears: What Gives You the Creeps?, p. 195

Changing the Behavior of Others: Alternatives to Punishment, p. 202

Déjà-Vu Experiences: An Illusion of Memory?, p. 246

H.M. and Famous People, p. 262

Does a High IQ Score Predict Success in Life?, p. 293

Neurodiversity: Beyond IQ, p. 298

Detecting Lies, p. 333

Everything You Wanted to Know About Sexual Fantasies, p. 424

Hooking Up on Campus, p. 425

Explaining Those Amazing Identical-Twin Similarities, p. 470

Interpersonal Attraction and Liking, p. 493

Providing Effective Social Support, p. 553

Gender Differences in Responding to Stress: “Tend-and-Befriend” or “Fight-or-Flight?”, p. 557

Using Virtual Reality to Treat Phobia and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, p. 628

Increasing Access: Meeting the Need for Mental Health Care, p. 638

Servant Leadership: When It’s Not All About You, p. B-10

Name, Title, Generation, p. B-11

Scientific Emphasis

Many first-time psychology students walk into the classroom operating on the assumption that psychology is nothing more than common sense or a collection of personal opinions. Clearly, students need to walk away from an introductory psychology course with a solid understanding of the scientific nature of the discipline. To help you achieve that goal, in every chapter we show students how the scientific method has been applied to help answer different kinds of questions about behavior and mental processes.

Because we carefully guide students through the details of specific experiments and studies, they develop a solid understanding of how scientific evidence is gathered and the interplay between theory and research. And because we rely on original rather than secondary sources, students get an accurate presentation of both classic and contemporary psychological studies.

One unique way that we highlight the scientific method in Psychology is with our trademark Science Versus Pseudoscience boxes. In these boxes, students see the importance of subjecting various claims to the standards of scientific evidence. These boxes promote and encourage scientific thinking by focusing on topics that students frequently ask about in class. The seventh edition of Psychology includes the following Science Versus Pseudoscience boxes:

What Is a Pseudoscience?, p. 20

Phrenology: The Bumpy Road to Scientific Progress, p. 61

Brain Myths, p. 77

Subliminal Perception, p. 89

Can a DVD Program Your Baby to Be a Genius?, p. 366

Graphology: The “Write” Way to Assess Personality?, p. 473

Critical Thinking Emphasis

Another important goal of Psychology is to encourage the development of critical thinking skills. To that end, we do not present psychology as a series of terms, definitions, and facts to be skimmed and memorized. Rather, we try to give students an understanding of how particular topics evolve. In doing so, we also demonstrate the process of challenging preconceptions, evaluating evidence, and revising theories based on new evidence. In short, every chapter shows the process of psychological research—and the important role played by critical thinking in that enterprise.

Because we do not shrink from discussing the implications of psychological findings, students come to understand that many important issues in contemporary psychology are far from being settled. Even when research results are consistent, how to interpret those results can sometimes be the subject of considerable debate. As the authors of the text, we very deliberately try to be evenhanded and fair in presenting both sides of controversial issues. In encouraging students to join these debates, we often challenge them to be aware of how their own preconceptions and opinions can shape their evaluation of the evidence.

Beyond discussions in the text proper, every chapter includes one or more Critical Thinking boxes. These boxes are carefully designed to encourage students to think about the broader implications of psychological research—to strengthen and refine their critical thinking skills by developing their own positions on questions and issues that don’t always have simple answers. Each Critical Thinking box ends with two or three questions that you can use as a written assignment or for classroom discussion. The seventh edition of Psychology includes the following Critical Thinking boxes:

How to Think Like a Scientist, p. 31

“His” and “Her” Brains?, p. 72

ESP: Can Perception Occur Without Sensation?, p. 112

Is Hypnosis a Special State of Consciousness?, p. 158

Is Human Freedom Just an Illusion?, p. 204

Does Exposure to Media Violence Cause Aggressive Behavior?, p. 219

The Memory Wars: Recovered or False Memories?, p. 254

The Persistence of Unwarranted Beliefs, p. 284

Has Evolution Programmed Us to Overeat?, p. 322

Emotion in Nonhuman Animals: Laughing Rats, Silly Elephants, and Smiling Dolphins?, p. 338

The Effects of Child Care on Attachment and Development, p. 388

Gender Differences: Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Fields, p. 406

Freud Versus Rogers on Human Nature, p. 459

Freud Versus Bandura on Human Aggression, p. 463

Abuse at Abu Ghraib: Why Do Ordinary People Commit Evil Acts?, p. 510

Do Personality Factors Cause Disease?, p. 550

Are People with a Mental Illness as Violent as the Media Portray Them?, p. 568

Does Smoking Cause Major Depressive Disorder and Other Psychological Disorders?, p. 588

Do Antidepressants Work Better Than Placebos?, p. 654

Cultural Coverage

As you can see in Table 1 below, we weave cultural coverage throughout many discussions in the text. But because students are usually unfamiliar with cross-cultural psychology, we also highlight specific topics in Culture and Human Behavior boxes. These boxes increase student awareness of the importance of culture in many areas of human experience. They are unique in that they go beyond simply describing cultural differences in behavior. They show students how cultural influences shape behavior and attitudes, including the students’ own behavior and attitudes. The seventh edition of Psychology includes the following Culture and Human Behavior boxes:

What Is Cross-Cultural Psychology?, p. 13

Ways of Seeing: Culture and Top-Down Processes, p. 114

Culture and the Müller-Lyer Illusion: The Carpentered-World Hypothesis, p. 126

Culture’s Effects on Early Memories, p. 237

The Effect of Language on Perception, p. 286

Performing with a Threat in the Air: How Stereotypes Undermine Performance, p. 304

Where Does the Baby Sleep?, p. 362

The Outward Display of Gender, p. 414

Explaining Failure and Murder: Culture and Attributional Biases, p. 490

The Stress of Adapting to a New Culture, p. 538

Culture-Bound Syndromes, p. 592

Cultural Values and Psychotherapy, p. 645

Integrated Cultural Coverage

| In addition to the topics covered in the Culture and Human Behavior boxes, cultural influences are addressed in the following discussions. | |

| Page(s) | Topic |

| 12 | Cross-cultural perspective in contemporary psychology |

| 12 | Culture, social loafing, and social striving |

| 51 | Effect of traditional Chinese acupuncture on endorphins |

| 102 | Cross-cultural research on the language of smell in non-Western groups |

| 108 | Cross-cultural research on effects of ethnicity and culture on pain perception |

| 127– |

Use of acupuncture in traditional Chinese medicine for pain relief |

| 160– |

Meditation in different cultures |

| 162 | Research collaboration between Tibetan Buddhist monks and Western neuroscientists |

| 165 | Racial and ethnic differences in drug metabolism rate |

| 165 | Cultural norms and patterns of drug use |

| 165 | Differences in alcohol use by U.S. ethnic groups |

| 170– |

Tobacco and caffeine use in different cultures |

| 173 | Peyote use in religious ceremonies in other cultures |

| 174 | Medicinal use of marijuana in ancient China, Egypt, India, and Greece |

| 174– |

Rave culture and drug use in Great Britain and Europe |

| 204 | Clash of B. F. Skinner’s philosophy with American cultural ideals and individualistic orientation |

| 218– |

Cross-cultural application of observational learning principles in entertainment-education programming in Mexico, Latin America, Asia, and Africa |

| 239– |

Cross-cultural research on the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon |

| 287 | Spontaneous development of sign languages in a Nicaraguan school and a Bedouin village as cross-cultural evidence of innate human predisposition to develop language |

| 288 | Estimated rate of bilingualism worldwide |

| 291– |

Historical misuse of IQ tests to evaluate immigrants |

| 292 | Wechsler’s recognition of the importance of culture and ethnicity in developing the WAIS intelligence test |

| 296– |

Role of culture in Gardner’s definition and theory of intelligence |

| 297– |

Role of culture in Sternberg’s definition and theory of intelligence |

| 301 | IQ and cross-cultural comparison of educational differences |

| 304– |

Rapid gains in IQ scores in different nations |

| 305– |

Cross-cultural studies of group discrimination and IQ |

| 307 | Role of culture in tests and test-taking behavior |

| 317– |

Culture’s effect on food preference and eating behavior |

| 321 | Role of globalization in the increase of obesity in developing countries worldwide |

| 322 | Rates of sedentary lifestyles worldwide |

| 323 | Obesity rates in cultures with different levels of economic development |

| 329 | Culture and achievement motivation |

| 331 | Culturally universal emotions |

| 331– |

Culture and emotional experience |

| 331– |

Cross-cultural research on gender and emotional expressiveness |

| 334 | Cross-cultural studies of psychological arousal associated with emotions |

| 334 | Cross-cultural research on association of different emotions with different physical sensations |

| 338– |

Universal facial expressions |

| 338– |

Culture, cultural display rules, and emotional expression |

| 362 | Cross-cultural research on co-sleeping |

| 363 | Cultural influences on temperament |

| 363 | Cross-cultural studies of attachment |

| 365 | Native language and infant language development |

| 365 | Cross-cultural research on infant-directed speech |

| 365 | Culture and patterns of language development |

| 373 | Influence of culture on cognitive development |

| 379 | Cultural influences on timing of adolescent romantic relationships |

| 383 | Culture and moral reasoning |

| 394 | Cultural differences in the effectiveness of different parenting styles |

| 402 | Culture’s influence on gender and gender roles |

| 402 | Gender stereotypes in different cultures |

| 404– |

Cross-cultural research on gender differences in emotional expression |

| 406 | Cross-cultural research on cognitive differences between the sexes |

| 411– |

Cultural differences in mate preferences |

| 414 | Role of culture in the expression of gender |

| 431– |

Prevalence rates of AIDS among different ethnic and racial groups in the United States and in different societies worldwide |

| 443– |

Freud’s impact on Western culture |

| 444– |

Cultural influences on Freud’s psychoanalytic theory |

| 453– |

Cultural influences on Jung’s personality theory |

| 454 | Jung on archetypal images, including mandalas, in different cultures |

| 454– |

Cultural influences on the development of Horney’s personality theory |

| 459 | Rogers on cultural factors in the development of antisocial behavior |

| 467 | Cross-cultural research on the universality of the five-factor model of personality |

| 486– |

Cultural conditioning and the “what is beautiful is good” myth |

| 490 | Attributional biases in individualistic versus collectivistic cultures |

| 493 | Cultural differences in interpersonal attraction |

| 496– |

Stereotypes, prejudice, and group identity |

| 500 | Use of IAT to study social preferences and stereotypes worldwide |

| 501 | Application of lessons from Robbers Cave and jigsaw classroom to reduce prejudice and conflict among ethnic and religious groups worldwide |

| 509 | Cross-cultural comparisons of destructive social influence |

| 510– |

Role of cultural differences in abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq |

| 518– |

Culture and aggression |

| 521 | Cultural influences on social loafing and social striving |

| 534 | Cross-cultural research on life events and stress |

| 537– |

Cultural differences as source of stress |

| 547 | Cross-cultural research on the benefits of perceived control |

| 558– |

Effect of culture on coping strategies |

| 567 | Role of culture in distinguishing between normal and abnormal behavior |

| 569 | Description of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases |

| 570– |

Global rates of mental illness |

| 571 | Cultural differences in rates of mental health treatment |

| 575 | Cultural variants of panic disorder |

| 576 | Taijin kyofusho, a culture-specific disorder related to social phobia |

| 578– |

PTSD in children living in a war zone in the Middle East and in child soldiers in Uganda and Congo |

| 581 | Cultural influences in obsessions and compulsions |

| 592– |

Culture-bound syndromes |

| 592 | Western cultural ideals of beauty and prevalence rates of eating disorders |

| 597 | Cultural differences in rates of borderline personality disorder |

| 598 | Role of culture in dissociative experiences |

| 604– |

Cultural variations in schizophrenia symptoms |

| 605 | Prevalence and differences in outcome of schizophrenia in different cultures |

| 610– |

Findings from the Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia |

| 622 | Use of interpersonal therapy to treat depression in Uganda |

| 638– |

Mechanisms for increasing access to mental health care worldwide |

| 644– |

Impact of cultural differences on effectiveness of psychotherapy |

| 647 | Efficacy of traditional herbal treatment for psychotic symptoms in India |

Gender Coverage

Gender influences and gender differences are described in many chapters. Table 2 below shows the integrated coverage of gender-related issues and topics in Psychology. To help identify the contributions made by female researchers, the full names of researchers are provided in the References section at the end of the text. When researchers are identified using initials instead of first names (as APA style recommends), many students automatically assume that the researchers are male.

Integrated Gender Coverage

| Page(s) | Topic |

|---|---|

|

4– |

Titchener’s inclusion of female graduate students in his psychology program in the late 1800s |

| 6 | Contributions of Mary Whiton Calkins to psychology |

|

6– |

Contributions of Margaret Floy Washburn to psychology |

| 58– |

Endocrine system and effects of sex hormones |

| 72 | Sex differences and the brain |

| 97 | Gender differences in incidence of color blindness |

| 103 | Gender differences in responses to human chemosignals (pheromones) |

| 107 | Gender differences in the perception of pain |

| 148 | Gender differences in dream content |

| 149 | Gender and nightmare frequency |

| 152 | Gender differences in driving while sleepy and traffic accidents related to sleepiness |

| 153– |

Gender differences in incidence of insomnia and other sleep disorders |

| 167 | Gender and rate of metabolism of alcohol |

| 167 | Gender and binge drinking among college students |

| 184 | Women as research assistants in Pavlov’s laboratories |

| 305 | Test performance and the influence of gender stereotypes |

| 304– |

Language, gender stereotypes, and gender bias |

| 322 | Gender differences in sedentary lifestyles |

| 323 | Gender differences in metabolism |

| 332 | Gender and emotional experience |

| 340 | Gender similarities and differences in experience and expression of emotion |

| 340 | Gender differences in cultural display rules and emotional expression |

| 355 | Sex differences in genetic transmission of recessive characteristics |

| 375– |

Gender differences in timing of the development of primary and secondary sex characteristics |

| 377 | Gender and accelerated puberty in father-absent homes |

| 378 | Gender differences in effects of early and late maturation |

| 383 | Gender differences in moral reasoning |

| 385 | Average age of first marriage and higher education attainment |

| 386 | Gender differences in single-parent, head-of-household status |

| 386 | Gender differences in response to end of reproductive capabilities |

| 386– |

Gender and patterns of career development and parenting responsibilities |

| 389 | Gender differences in life expectancy |

| 401 | Definitions of gender and gender role |

| 401– |

Gender stereotypes and gender roles |

| 404 | Gender differences in personality |

| 404 | Gender differences in emotionality |

| 405-406 | Cognitive differences in males and females |

| 406-407 | Women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields |

| 407 | Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors |

| 408– |

Gender differences in childhood behavior |

| 410– |

Development of gender identity and gender roles |

| 410– |

Theories of gender-role development |

| 410– |

Gender-identity development in Freud’s psychoanalytic theory |

| 417 | Sex differences in the pattern of human sexual response |

| 417– |

Sex differences in hormonal influences on sexual motivation |

| 424 | Gender differences in sexual fantasies |

| 425– |

Gender differences in sexual behavior |

| 428 | Gender differences in rates of sexual problems |

| 450– |

Freud’s contention of gender differences in resolving the Oedipus complex |

| 453 | Sexual archetypes (anima, animus) in Jung’s personality theory |

| 454– |

Horney’s critique of Freud’s view of female psychosexual development |

| 457 | Critique of sexism in Freud’s theory |

| 493 | Gender similarities and differences in interpersonal attraction |

| 496 | Misleading effect of gender stereotypes |

| 506– |

Gender similarities in results of Milgram’s obedience studies |

| 518– |

Gender and aggression |

| 535– |

Gender differences in frequency and source of daily hassles |

| 552– |

Gender differences in susceptibility to the stress contagion effect |

| 552– |

Gender differences in providing social support and effects of social support |

| 557 | Gender differences in responding to stress—the “tend-and-befriend” response |

| 570 | Gender bias as one critique of DSM-5 |

| 573 | Gender differences in prevalence of anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders |

| 576 | Gender differences in prevalence of specific phobias |

| 576 | Gender differences in prevalence of social phobias |

| 578 | Gender differences in prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder |

| 584 | Gender differences in prevalence of major depressive disorder |

| 586 | Lack of gender differences in prevalence of bipolar disorder |

| 590 | Gender differences in prevalence of eating disorders |

| 596 | Gender differences in incidence of antisocial personality disorder |

| 597 | Gender differences in incidence of borderline personality disorder |

| 607 | Paternal age and incidence of schizophrenia |

| 612 | Gender differences in number of suicide attempts and in number of suicide deaths |

| 659 | Gender differences in sexual contact between therapists and clients |

| B-12 | Gender differences in reasons for wanting to telecommute |

Neuroscience Coverage

Psychology and neuroscience have become intricately intertwined. Especially in the last decade, the scientific understanding of the brain and its relation to human behavior has grown dramatically. The imaging techniques of brain science—PET scans, MRIs, and functional MRIs—have become familiar terminology to many students, even if they don’t completely understand the differences between them. To reflect that growing trend, we have increased our neuroscience coverage to show students how understanding the brain can help explain the complete range of human behavior, from the ordinary to the severely disturbed. Each chapter contains one or more Focus on Neuroscience discussions that are designed to complement the broader chapter discussion. Here is a complete list of the Focus on Neuroscience features in the seventh edition:

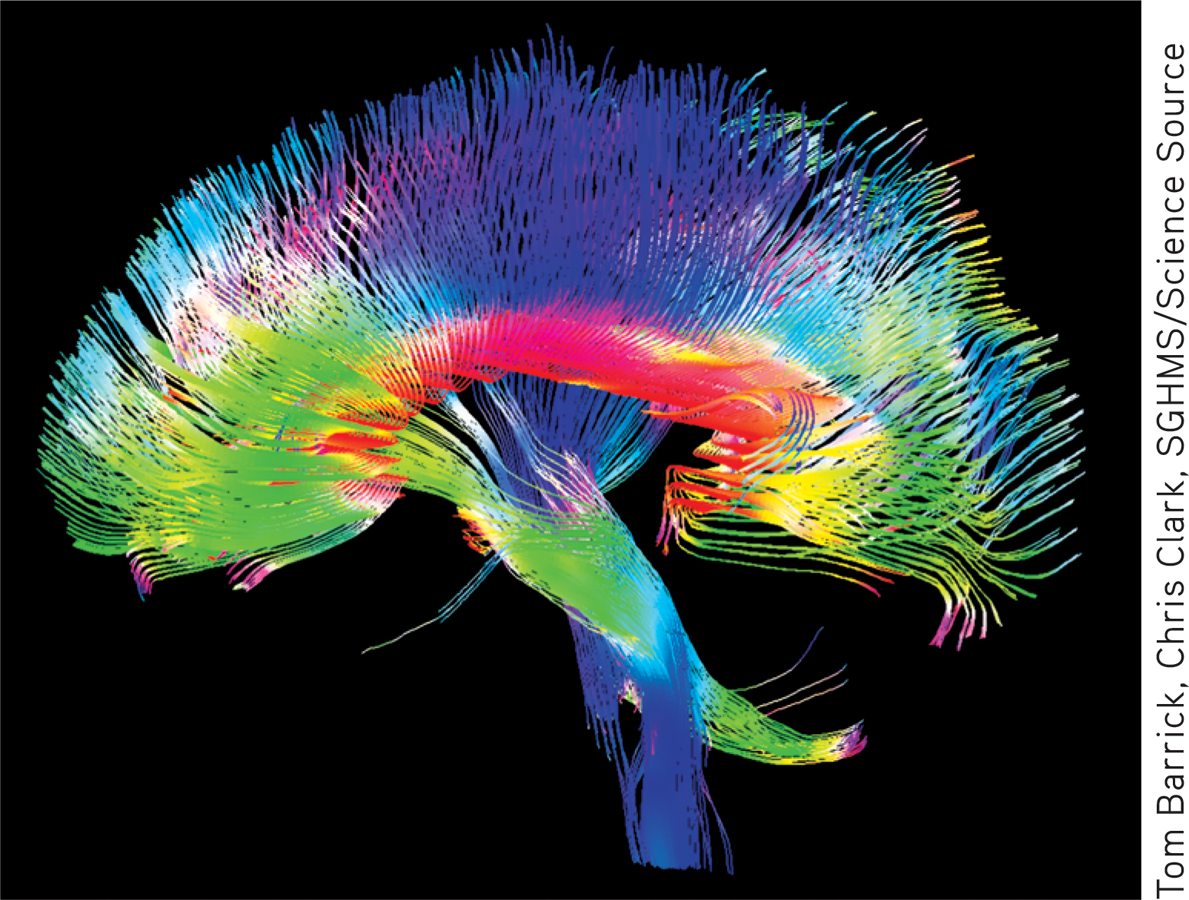

Psychological Research Using Brain Imaging, p. 32

Mapping the Pathways of the Brain, p. 62

Juggling and Brain Plasticity, p. 63

Vision, Experience, and the Brain, p. 95

The Sleep-Deprived Emotional Brain, p. 146

The Dreaming Brain, p. 148

Meditation and the Brain, p. 163

The Addicted Brain: Diminishing Rewards, p. 166

How Methamphetamines Erode the Brain, p. 173

Mirror Neurons: Imitation in the Brain, p. 217

Assembling Memories: Echoes and Reflections of Perception, p. 258

Mapping Brain Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease, p. 264

Seeing Faces and Places in the Mind’s Eye, p. 274

Dopamine Receptors and Obesity, p. 324

Emotions and the Brain, p. 336

The Adolescent Brain: A Work in Progress, p. 376

Boosting the Aging Brain, p. 391

Romantic Love and the Brain, p. 423

The Neuroscience of Personality: Brain Structure and the Big Five, p. 469

Brain Reward When Making Eye Contact with Attractive People, p. 488

The Mysterious Placebo Effect, p. 544

The Hallucinating Brain, p. 602

Schizophrenia: A Wildfire in the Brain, p. 609

Psychotherapy and the Brain, p. 653

Psych for Your Life

Among all the sciences, psychology is unique in the degree to which it speaks to our daily lives and applies to everyday problems and concerns. The Psych for Your Life feature at the end of each chapter presents the findings from psychological research that address a wide variety of problems and concerns. In each of these features, we present research-based information in a form that students can use to enhance everyday functioning. As you can see in the following list, topics range from improving self-control to overcoming insomnia:

Successful Study Techniques, p. 36

Maximizing Your Brain’s Potential, p. 79

Strategies to Control Pain, p. 127

Overcoming Insomnia, p. 176

Using Learning Principles to Improve Your Self-Control, p. 222

Ten Steps to Boost Your Memory, p. 266

A Workshop on Creativity, p. 308

Turning Your Goals into Reality, p. 346

Raising Psychologically Healthy Children, p. 393

Reducing Conflict in Intimate Relationships, p. 438

Possible Selves: Imagine the Possibilities, p. 478

The Persuasion Game, p. 523

Minimizing the Effects of Stress, p. 560

Understanding and Helping to Prevent Suicide, p. 612

What to Expect in Psychotherapy, p. 658

The Pedagogical System

The pedagogical system in Psychology was carefully designed to help students identify important information, test for retention, and learn how to learn. It is easily adaptable to an SQ3R approach, for those instructors who have had success with that technique. As described in the following discussion, the different elements of this text form a pedagogical system that is very student-friendly, straightforward, and effective.

We’ve found that it appeals to diverse students with varying academic and study skills, enhancing the learning process without being gimmicky or condescending. A special student preface titled To the Student on pages xlviii to li, immediately before Chapter 1, describes the complete pedagogical system and demonstrates how students can make the most of it.

The pedagogical system has four main components: (1) Advance Organizers, (2) Concept Reviews, (3) Chapter Reviews, and (4) LaunchPad for Psychology, Seventh Edition. Major sections are introduced by an Advance Organizer that identifies the section’s Key Theme followed by a bulleted list of Key Questions. Each Advance Organizer mentally primes the student for the important information that is to follow and does so in a way that encourages active learning. Students often struggle with trying to determine what’s important to learn in a particular section or chapter. As a pedagogical technique, the Advance Organizer provides a guide that directs the student toward the most important ideas, concepts, and information in the section. It helps students identify main ideas and distinguish them from supporting evidence and examples.

The Concept Reviews encourage students to review and check their learning at appropriate points in the chapter. As you look through the text, you’ll see that the Concept Reviews vary in format. They include multiple-choice, matching, short-answer, and true-false questions. Many of the Concept Reviews are interactive exercises that help students transfer their learning to new situations or examples.

Several other in-chapter pedagogical aids support the Advance Organizers and Concept Reviews. A clearly identified Chapter Outline provides an overview of topics and organization. Pronunciation guides are included for difficult or unfamiliar words. Because students often have trouble identifying the most important theorists and researchers, names of key people are set in boldface type within the chapter. We also provide a page-referenced list of key people and key terms at the end of each chapter.

Multimedia to Support Teaching and Learning

LaunchPad with LearningCurve Quizzing

A comprehensive Web resource for teaching and learning psychology, LaunchPad combines Worth Publishers’ awarding-winning media with an innovative platform for easy navigation. For students, it is the ultimate online study guide with rich interactive tutorials, videos, e-Book, and the LearningCurve adaptive quizzing system. For instructors, LaunchPad is a full-course space where class documents can be posted, quizzes are easily assigned and graded, and students’ progress can be assessed and recorded. Whether you are looking for the most effective study tools or a robust platform for an online course, LaunchPad is a powerful way to enhance your class. You can preview LaunchPad to accompany Psychology at www.launchpadworks.com

Psychology and LaunchPad can be ordered together with ISBN-10: 1-319-01709-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-319-01709-5

LaunchPad for Psychology includes all the following resources: