Chapter Introduction

MYTH OR SCIENCE?

Is it true …

That most psychologists today agree with Sigmund Freud’s personality theory?

That personality traits change quite a bit over the course of our lives?

That personality is not influenced by genetics, but is primarily shaped by your upbringing?

That handwriting analysis provides insights into your personality and predicts occupational success?

That projective tests, like the famous Rorschach inkblot test, accurately reveal personality traits and unconscious conflicts?

That it’s easy to fake the results of personality tests?

That if you can imagine yourself taking the steps to become successful, you’re more likely to actually become successful?

11

Personality

Ella Boyd

The Secret Twin

PROLOGUE

IN THIS CHAPTER:

THE TWINS, KENNETH AND JULIAN, were born a few years after the turn of the last century. At first, their parents, Gertrude and Henry, thought they were identical. Both had dark hair and deep brown eyes. Many years later, Kenneth’s son, your author Don, would inherit these qualities.

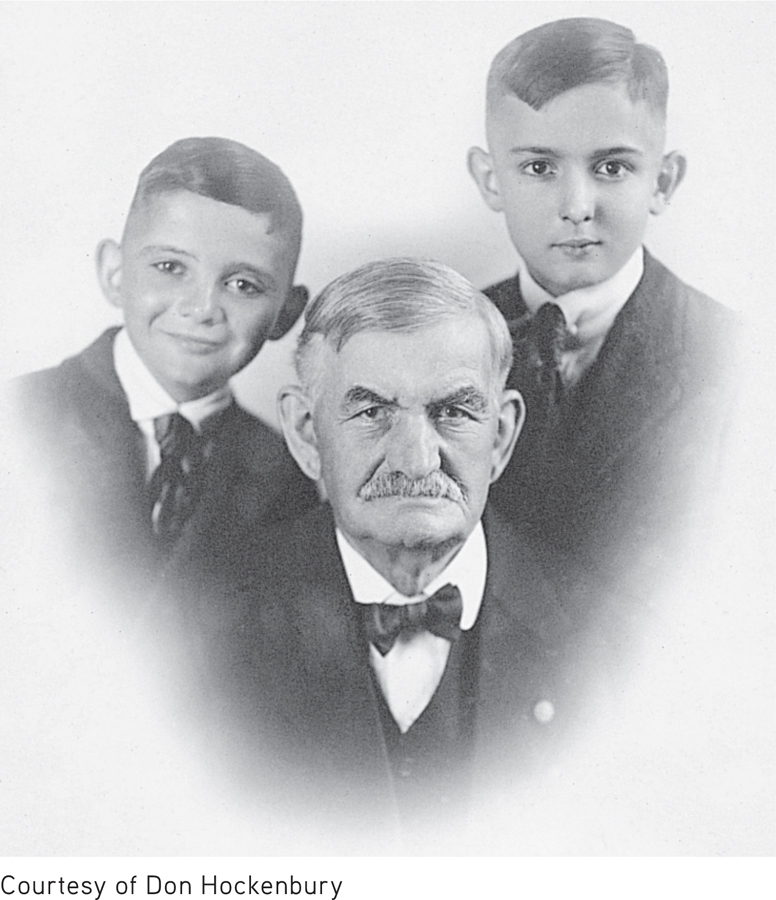

But Gertrude and Henry quickly learned to tell the twins apart. Kenneth was slightly larger than Julian, and, even as infants, their personalities were distinctly different. In the photographs of Kenneth and Julian as children, Julian smiles broadly, almost merrily, his head cocked slightly. But Kenneth always looks straight at the camera, his expression thoughtful, serious, more intense.

We don’t know much about Julian’s childhood. Kenneth kept Julian’s existence a closely guarded secret for more than 50 years. In fact, it was only a few years before his own death that Kenneth revealed that he had once had a twin brother named Julian.

Still, it’s possible to get glimpses of Julian’s early life from the letters the boys wrote home from summer camp in 1919 and 1920. Kenneth’s letters to his mother were affectionate and respectful, telling her about their daily activities and reassuring her that he would look after his twin brother. “I reminded Julian about the boats and I will watch him good,” Kenneth wrote in one letter. Julian’s letters were equally affectionate, but shorter and filled with misspelled words. Julian’s letters also revealed glimpses of his impulsive nature. He repeatedly promised his mother, “I will not go out in the boats alone again.”

Julian’s impulsive nature was to have a significant impact on his life. When he was 12 years old, Julian darted in front of a car and was seriously injured, sustaining a concussion. In retrospect, Kenneth believed that that was when Julian’s problems began. Perhaps it was, because not long after the accident Julian got into serious trouble for the first time: He got caught red-handed stealing money from the “poor box” at church.

Although Kenneth claimed that Julian had always been the smarter twin, Julian fell behind in high school and graduated a year later than Kenneth. After high school, Kenneth left the quiet farming community of Grinnell, Iowa, and moved to Minneapolis. He quickly became self-sufficient, taking a job managing newspaper carriers. Julian stayed in Grinnell and became apprenticed to learn typesetting. Given Julian’s propensity for adventure, it’s not surprising that he found typesetting monotonous. So in the spring of 1928, Julian quit typesetting. He also decided to leave Iowa and head east to look for more interesting possibilities.

He found them in Tennessee. A few months after Julian left Iowa, Henry received word that Julian had been arrested for armed robbery and sentenced to 15 years in a Tennessee state prison. Though Kenneth was only 22 years old, Henry gave him a large sum of money and the family car and sent him to try to get Julian released.

Kenneth’s conversation with the judge in Knoxville was the first of many times that he would deal with the judicial system on someone else’s behalf. After much negotiation, the judge agreed: If Julian promised to leave Tennessee and never return, and Kenneth paid the cash “fines,” Julian would be released from prison.

When Julian walked through the prison gates the next morning, Kenneth stood waiting with a fresh suit of clothes. “Mother and Father want you to come back to Grinnell,” he told Julian. But Julian would not hear of it, saying that instead he wanted to go to California to seek his fortune.

“I can’t let you do that, Julian,” Kenneth said, looking hard at his twin brother.

“You can’t stop me, brother,” Julian responded, with a cocky smile. Reluctantly, Kenneth kept just enough money to buy himself a train ticket back to Iowa. He gave Julian the rest of the money and the family car.

Julian got as far as Phoenix, Arizona, before he met his destiny. In broad daylight, he robbed a drugstore at gunpoint. As he backed out of the store, a policeman spotted him. A gun battle followed, and Julian was shot twice. Somehow he managed to escape and holed up in a hotel room. Alone and untended, Julian died two days later from the bullet wounds. Once again, Kenneth was sent to retrieve his twin brother.

On a bitterly cold November morning in 1928, Julian’s immediate family laid him to rest in the family plot in Grinnell. On the one hand, Kenneth felt largely responsible for Julian’s misguided life. “I should have tried harder to help Julian,” Kenneth later reflected. On the other hand, Julian had disgraced the family. From the day Julian was buried, the family never spoke of him again, not even in private.

Kenneth took it upon himself to atone for the failings of his twin brother. In the fall of 1929, he entered law school in Tennessee—the same state from which he had secured Julian’s release from prison. Three years later, at the height of the Great Depression, Kenneth established himself as a lawyer in Sioux City, Iowa, where he would practice law for more than 50 years.

As an attorney, Kenneth Hockenbury was known for his integrity, his intensity in the courtroom, and his willingness to take cases regardless of the client’s ability to pay. “Someone must defend the poor,” he said repeatedly. In lieu of money, he often accepted labor from a working man or produce from farmers.

Almost sixty years after Julian’s death, Kenneth died. But unlike the sparse gathering that had attended Julian’s burial, scores of people came to pay their last respects to Kenneth Hockenbury. “Your father helped me so much,” stranger after stranger told Don at Kenneth’s funeral. Without question, Kenneth had devoted his life to helping others.

Why did Kenneth and Julian turn out so differently? Two boys, born on the same day into the same middle-class family. Kenneth the conscientious, serious one; Julian the laughing boy with mischief in his eyes. How can we explain the fundamental differences in their personalities?

No doubt your family, too, is made up of people with very different personalities. By the end of this chapter, you’ll have a much greater appreciation for how psychologists explain such personality differences.