Choosing a style and design

Choosing a style and design

Narratives are usually written in approachable middle or low styles because they nicely mimic the human voice through devices such as contractions and dialogue. Both styles are also comfortable with I, the point of view of many stories. A middle style may be perfect for reaching academic or professional audiences. But a low style, dipping into slang and unconventional speech, may sometimes feel more authentic to more general readers. It’s your choice.

Style is important because narratives get their energy and textures from sentence structures and vocabulary choices. Narratives require tight but expressive language — tight to keep the action moving, expressive to capture the gist of events. In a first draft, run with your ideas and don’t do much editing. Flesh out the story as you have designed it and then go back to see if it works technically: Characters should be introduced, locations identified and colored, events clearly explained and sequenced, key points made memorably and emphatically. You’ll need several drafts to get these key elements into shape.

Then look to your language and allow plenty of time to revise it. Begin with Chapter 34, “Vigorous, Clear, Economical Style.” Here are some options for your narrative.

Don’t hesitate to use first person — I. Most personal narratives are about the writer, so first-person pronouns are used without apology. (define your style) A narrative often must take readers where the I has been, and using the first-person pronoun helps make writing authentic. Consider online journalist Michael Yon’s explanation of why he reported on the Iraq War using I rather than a more objective third-person perspective:

I write in first person because I am actually there at the events I write about. When I write about the bombs exploding, or the smell of blood, or the bullets snapping by, and I say I, it’s because I was there. Yesterday a sniper shot at us, and seven of my neighbors were injured by a large bomb. These are my neighbors. These are soldiers. . . . I feel the fire from the explosions, and am lucky, very lucky, still to be alive. Everything here is first person.

— From Glenn Reynolds, An Army of Davids

And yet don’t count out telling a story from a third-person point of view, even when you are writing about yourself. You may find it bracing to present yourself as someone else might see you.

Use figures of speech such as similes, metaphors, and analogies to make memorable comparisons. Similes make comparisons by using like or as: He used his camera like a rifle. Metaphors drop the like or as to gain even more power: His camera was a rifle aimed at enemies. An analogy extends the comparison: His camera became a rifle aimed at his imaginary enemies, their private lives in his crosshairs.

People make comparisons habitually. Some are so common they’ve been reduced to invisible clichés: hit me like a ton of bricks; dumb as an ox; clear as a bell. In your own narratives, you want similes and metaphors fresher than these and yet not contrived or strained. Here’s science writer Michael Chorost effortlessly deploying both a metaphor (spins up) and a simile (like riding a roller coaster) to describe what he experiences as he awaits surgery.

I can feel the bustle and clatter around me as the surgical team spins up to take-off speed. It is like riding a roller coaster upward to the first great plunge, strapped in and committed.

— Rebuilt: How Becoming Part Computer Made Me More Human

Need help seeing the big picture? See "How to Revise Your Work"

In choosing verbs, favor active rather than passive voice. Active verbs propel the action (Estela signed the petition), while passive verbs slow it down by an unneeded word or two (The petition was signed by Estela). (improve your sentences)

Since narratives are all about movement, build sentences around strong verbs that do things. Edit until you get down to the nub of the action. You will produce sentences as effortless as these from Joseph Epstein, describing the pleasures of catching plagiarists. (avoid plagiarism) Verbs are highlighted in this passage; only one (is followed) is passive.

In thirty years of teaching university students I never encountered a case of plagiarism, or even one that I suspected. Teachers I’ve known who have caught students in this sad act report that the capture gives one an odd sense of power. The power derives from the authority that resides behind the word gotcha. This is followed by that awful moment — a veritable sadist’s Mardi Gras — when one calls the student into one’s office and points out the odd coincidence that he seems to have written about existentialism in precisely the same words Jean-Paul Sartre used fifty-two years earlier.

— “Plagiary, It’s Crawling All Over Me,” Weekly Standard, March 6, 2006

Keep the language simple. Your language need not be elaborate when it is fresh and authentic. Look for concrete expressions that help readers visualize a scene. And when it comes to modifiers, one strong word is usually better than several weaker ones (freezing rather than very cold; doltish rather than not very bright). In the paragraph below from a narrative about telling ghost stories, notice how simple items clearly detailed (oil lamp, soft blankets, pan dulce) draw you into the scene.

When we tell scary stories, we’re usually in the half-light of an old oil lamp that my Tío Fernando brings out from the storage room in back. Its flame flickers on the walls — creating dancing shadows — and the smell of oil permeates the room. We pass soft blankets around to cuddle beneath and keep terrors at bay. Snacks are set on the kitchen table for us to munch on: chips with spicy hot sauce, pan dulce, leftover burritos de chile colorado from earlier in the day. We make ourselves comfortable and settle in for a long night — one full of chills that will likely give us nightmares.

— Alexandra Rayo, “The Thrill of Terror”

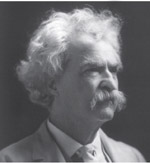

The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—it's the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.

—Mark Twain

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-5513.

Develop major characters through action and dialogue. It’s usually better to portray people via their words and actions than through static descriptions: The mantra is, show, don’t tell. Remember it! If a character is conceited or cheap, let readers see him glancing in mirrors or heading to the restroom as the lunch bill arrives.

You can also bring people to life in a story by what they say — and without much commentary from you. Just be sure your characters’ lines sound natural, following the advice of author John Steinbeck: “If you are using dialogue — say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.” Avoid using dialogue to explain complicated plot points. No one believes it when characters plunge into detailed (and perfectly grammatical) passages of exposition: “Oh look, the house is in flames and here comes the first of several emergency vehicles!” No dialogue is better than awkward dialogue.

The following is a selection from a personal narrative about a student’s trip to South Africa that artfully melds precise observation, deft characterization, and believable dialogue. Note, too, how the use of the present tense makes the moment seem immediate and dramatic.

At last we arrive at the Ikageng Itereleng AIDS Ministry center, a sanctuary that emerges from a cloud of dust. It is an organization run by Carol Dyanti. She is everyone’s mama, a hero to her community. From her modest building she passes out food, clothing, and school supplies to families in need. But all the families are in need. I watch as Carol embraces two bashful young women with their gazes fixed downward. She sends them away with a gallon of cooking oil and a sack of corn meal for mieliepap.

Carol turns to us and offers the same loving hugs.

“Those two,” she tells me, “they’re sisters, twelve and fourteen. They live alone now because their parents abandoned them. They can’t even go to school because they must work now.”

I watch them walk away. They have no smiles, no girlish giggles, or sisterly quarrels. They walk slowly, bent against a crisp winter wind.

Carol runs her organization from donations of both supplies and money from outreach groups. Some groups are local, but most are from Western countries. Oprah Winfrey, for example, has given money and vans to help Ikageng Itereleng.

“But see, she just comes in and gives money — there is no thought behind it,” Carol tells me. “Sometimes we don’t see any of it because of how poorly everything is managed. She is a wonderful lady, but . . .” Carol pauses. “She only sees what she wants to see. And that doesn’t help us much.”

— Lily Parish, “Sala Kahle, South Africa,” 2013

For the record, dialogue ordinarily requires quotation marks and new paragraphs for each change of speaker. And keep the tags simple: You don’t have to vary much from he said or she said.

Develop the setting to set the context and mood. Show readers where and when events are occurring if the setting makes a difference — and most of the time it will. Location (Times Square; dusty street in Gallup, New Mexico; your bedroom), as well as climate and time of day (cool dawn, exotic dusk, broiling afternoon), will help readers get a fix on the story. But don’t churn out paragraphs of description just for their own sake; readers will skate right over them. (develop a draft)

Use images to tell a story. Consider the ways photos attached to a narrative might help readers grasp the setting and situation. More complex stories about your life or community can be told by combining your words and pictures in photo-essays or other media environments. (think visually) Or use images simply to illustrate a sequence of events. An illustrated timeline is a simple form of this sort of narrative, as are scrapbooks or high school yearbooks.

Note how the photograph conveys far more than the statistics alone would.

Courtesy of Sid Darion.