Finding and developing materials

Finding and developing materials

consider causes

Expect to do as much research for a causal analysis as for any fact-

Equally important is learning how exactly causal relationships work so that any claims you make about them are accurate. Causality is intriguing because it demands precision and subtlety — as the categories explained in this section demonstrate. But once you grasp them, you’ll also be better able to identify faulty causal claims when you come across them. (Exposing faulty causality makes for notably powerful and winning arguments.) (refine your search)

Understand necessary causes. A necessary cause is any factor that must be in place for something to occur. For example, sunlight, chlorophyll, and water are all necessary for photosynthesis to happen. Remove one of these elements from the equation and the natural process simply doesn’t take place. But since none of them could cause photosynthesis on their own, they are necessary causes, yet not sufficient (see sufficient causes below).

On a less scientific level, necessary causes are those that seem so crucial that we can’t imagine something happening without them. For example, you might argue that a team could not win a World Series without a specific pitcher on the roster: Remove him and the team doesn’t even get to the playoffs. Or you might claim that, while fanaticism doesn’t itself cause terrorism, terrorism doesn’t exist without fanaticism. In any such analysis, it helps to separate necessary causes from those that may be merely contributing factors.

Understand sufficient causes. A sufficient cause, by itself, is enough to bring on a particular effect. Driving drunk or shoplifting are two sufficient causes for being arrested in the United States. In a causal argument, you might need to figure out which of several plausible sufficient causes is responsible for a specific phenomenon — assuming that a single explanation exists. A plane might have crashed because it was overloaded, ran out of fuel, had a structural failure, encountered severe wind shear, and so on.

Understand precipitating causes. Think of a precipitating cause as the proverbial straw that breaks a camel’s back. In itself, the factor may seem trivial. But it becomes the spark that sets a field gone dry for months ablaze. By refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks triggered a civil rights movement in 1955, but she didn’t actually cause it: The necessary conditions had been accumulating for generations.

Need help assessing your own work? See “How to Use the Writing Center”.

Understand proximate causes. A proximate cause is nearby and often easy to spot. A corporation declares bankruptcy when it can no longer meet its massive debt obligations; a minivan crashes because a front tire explodes; a student fails a course because she plagiarizes a paper. But in a causal analysis, getting the facts right about such proximate causes may just be your starting point. You need to work toward a deeper understanding of a situation. As you might guess, proximate causes may sometimes also be sufficient causes.

Understand remote causes. A remote cause, as the term suggests, may act at some distance from an event but be closely tied to it. That bankrupt corporation may have defaulted on its loans because of a full decade of bad management decisions; the tire exploded because it was underinflated and its tread was worn; the student resorted to plagiarism because she ran out of time because she was working two jobs to pay for a Hawaiian vacation because she wanted a memorable spring break to impress her friends — a string of remote causes. Remote causes make many causal analyses challenging and interesting: Figuring them out is like detective work.

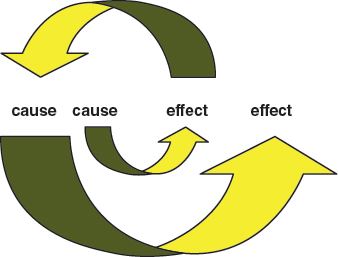

Understand reciprocal causes. You have a reciprocal situation when a cause leads to an effect that, in turn, strengthens the cause. Consider how creating science internships for college women might encourage more women to become scientists, who then sponsor more internships, creating yet more female scientists. Many analyses of global warming describe reciprocal relationships, with CO2 emissions supposedly leading to warming, which increases plant growth or alters ocean currents, which in turn releases more CO2 or heat, and so on.