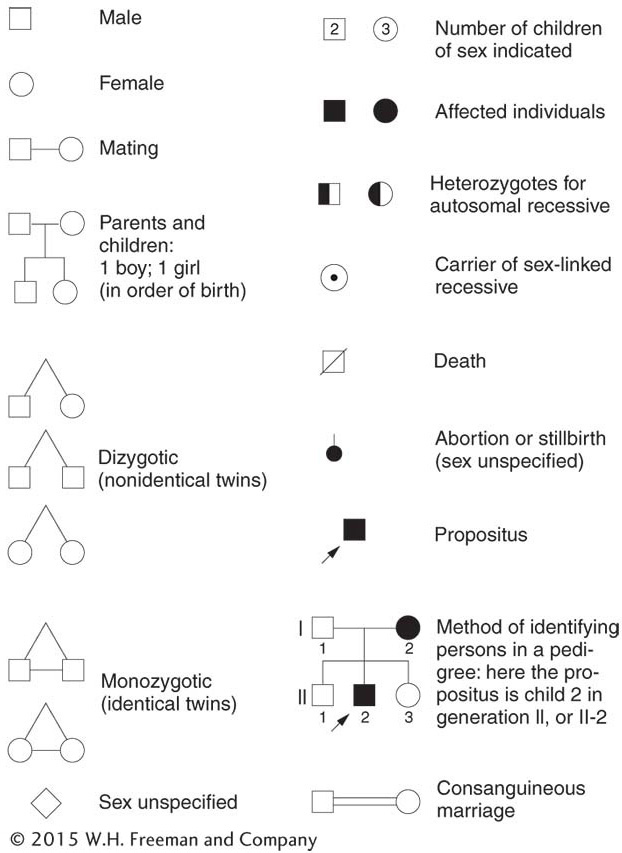

2.6 Human Pedigree Analysis

Human matings, like those of experimental organisms, provide many examples of single-

To see single-

Autosomal recessive disorders

The affected phenotype of an autosomal recessive disorder is inherited as a recessive allele; hence, the corresponding unaffected phenotype must be inherited as the corresponding dominant allele. For example, the human disease phenylketonuria (PKU), discussed earlier, is inherited in a simple Mendelian manner as a recessive phenotype, with PKU determined by the allele p and the normal condition determined by P. Therefore, people with this disease are of genotype p/p, and people who do not have the disease are either P/P or P/p. Recall that the term wild type and its allele symbols are not used in human genetics because wild type is impossible to define.

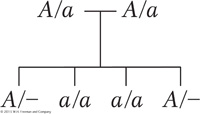

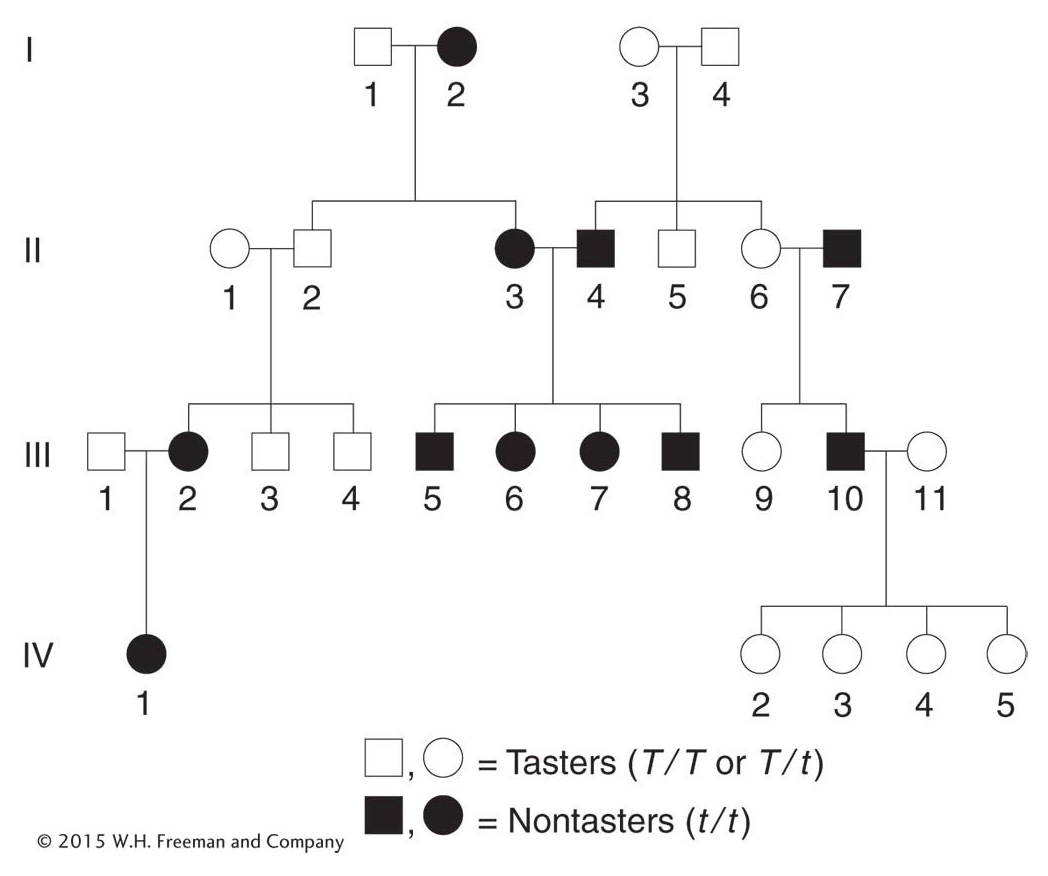

What patterns in a pedigree would reveal autosomal recessive inheritance? The two key points are that (1) generally the disorder appears in the progeny of unaffected parents and (2) the affected progeny include both males and females. When we know that both male and female progeny are affected, we can infer that we are most likely dealing with simple Mendelian inheritance of a gene on an autosome, rather than a gene on a sex chromosome. The following typical pedigree illustrates the key point that affected children are born to unaffected parents:

From this pattern, we can deduce a simple monohybrid cross, with the recessive allele responsible for the exceptional phenotype (indicated in black). Both parents must be heterozygotes—

This pedigree does not support the hypothesis of X-

Notice that, even though Mendelian rules are at work, Mendelian ratios are not necessarily observed in single families because of small sample size, as predicted earlier. In the preceding example, we observe a 1:1 phenotypic ratio in the progeny of a monohybrid cross. If the couple were to have, say, 20 children, the ratio would be something like 15 unaffected children and 5 with PKU (a 3:1 ratio), but, in a small sample of 4 children, any ratio is possible, and all ratios are commonly found.

The family pedigrees of autosomal recessive disorders tend to look rather bare, with few black symbols. A recessive condition shows up in groups of affected siblings, and the people in earlier and later generations tend not to be affected. To understand why this is so, it is important to have some understanding of the genetic structure of populations underlying such rare conditions. By definition, if the condition is rare, most people do not carry the abnormal allele. Furthermore, most of those people who do carry the abnormal allele are heterozygous for it rather than homozygous. The basic reason that heterozygotes are much more common than recessive homozygotes is that, to be a recessive homozygote, both parents must have the a allele, but, to be a heterozygote, only one parent must have it.

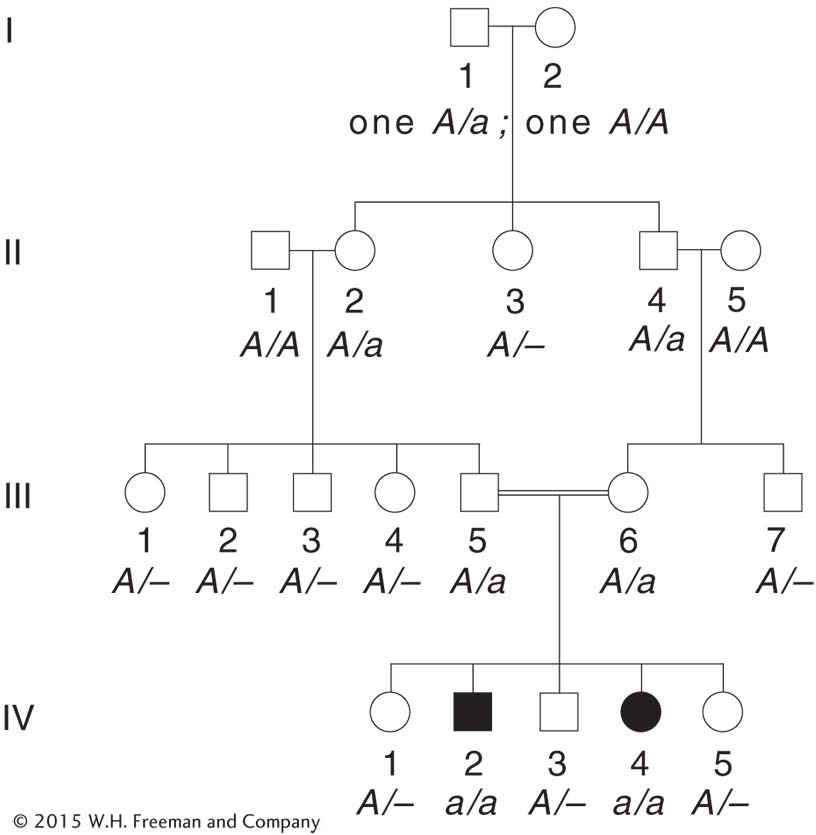

The birth of an affected person usually depends on the rare chance union of unrelated heterozygous parents. However, inbreeding (mating between relatives, sometimes referred to as consanguinity in humans) increases the chance that two heterozygotes will mate. An example of a marriage between cousins is shown in Figure 2-19. Individuals III-

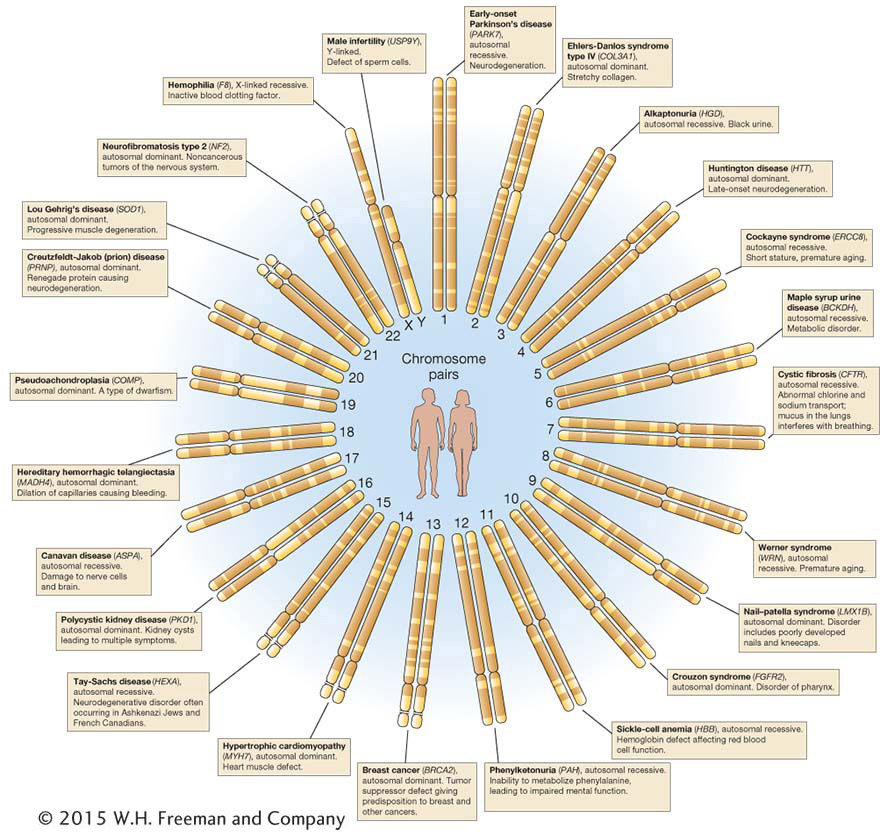

Some other examples of human recessive disorders are shown in Figure 2-20. Cystic fibrosis is a disease inherited on chromosome 7 according to Mendelian rules as an autosomal recessive phenotype. Its most important symptom is the secretion of large amounts of mucus into the lungs, resulting in death from a combination of effects but usually precipitated by infection of the respiratory tract. The mucus can be dislodged by mechanical chest thumpers, and pulmonary infection can be prevented by antibiotics; thus, with treatment, cystic fibrosis patients can live to adulthood. The cystic fibrosis gene (and its mutant allele) was one of the first human disease genes to be isolated at the DNA level, in 1989. This line of research eventually revealed that the disorder is caused by a defective protein that normally transports chloride ions across the cell membrane. The resultant alteration of the salt balance changes the constitution of the lung mucus. This new understanding of gene function in affected and unaffected persons has given hope for more effective treatment.

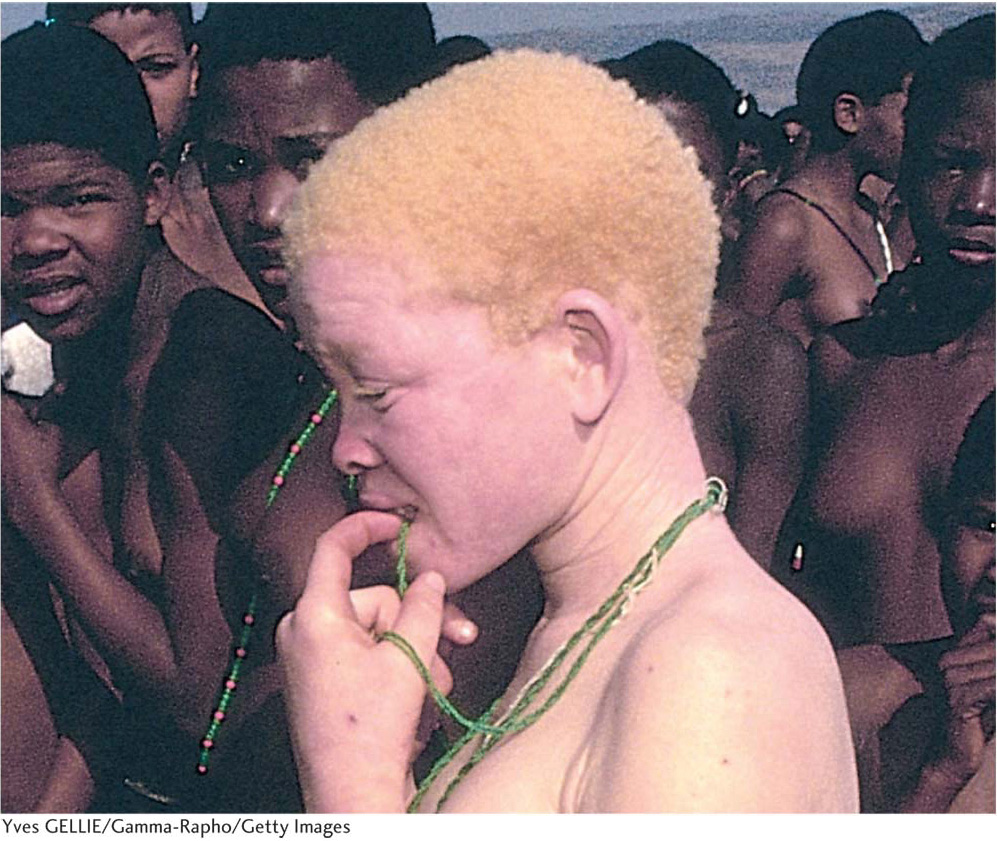

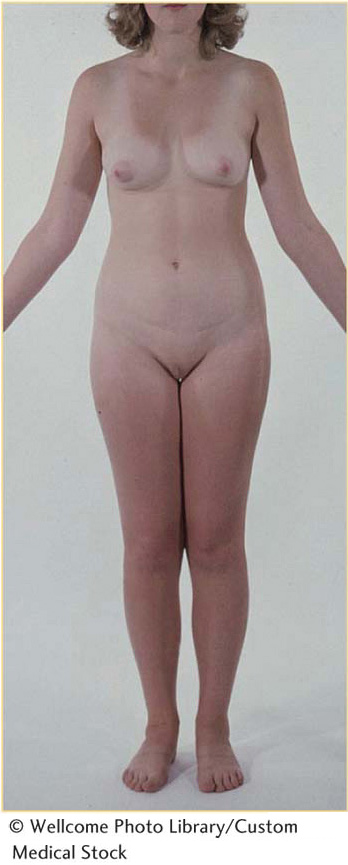

Human albinism also is inherited in the standard autosomal recessive manner. The mutant allele is of a gene that normally synthesizes the brown or black pigment melanin, normally found in skin, hair, and the retina of the eye (Figure 2-21).

KEY CONCEPT

In human pedigrees, an autosomal recessive disorder is generally revealed by the appearance of the disorder in the male and female progeny of unaffected parents.

Autosomal dominant disorders

What pedigree patterns are expected from autosomal dominant disorders? Here, the normal allele is recessive, and the defective allele is dominant. It may seem paradoxical that a rare disorder can be dominant, but remember that dominance and recessiveness are simply properties of how alleles act in heterozygotes and are not defined in reference to how common they are in the population. A good example of a rare dominant phenotype that shows single-

In pedigree analysis, the main clues for identifying an autosomal dominant disorder with Mendelian inheritance are that the phenotype tends to appear in every generation of the pedigree and that affected fathers or mothers transmit the phenotype to both sons and daughters. Again, the equal representation of both sexes among the affected offspring rules out inheritance through the sex chromosomes. The phenotype appears in every generation because, generally, the abnormal allele carried by a person must have come from a parent in the preceding generation. (Abnormal alleles can also arise de novo by mutation. This possibility must be kept in mind for disorders that interfere with reproduction because, here, the condition is unlikely to have been inherited from an affected parent.) A typical pedigree for a dominant disorder is shown in Figure 2-23. Once again, notice that Mendelian ratios are not necessarily observed in families. As with recessive disorders, persons bearing one copy of the rare A allele (A/a) are much more common than those bearing two copies (A/A); so most affected people are heterozygotes, and virtually all matings that produce progeny with dominant disorders are A/a × a/a. Therefore, if the progeny of such matings are totaled, a 1:1 ratio is expected of unaffected (a/a) to affected (A/a) persons.

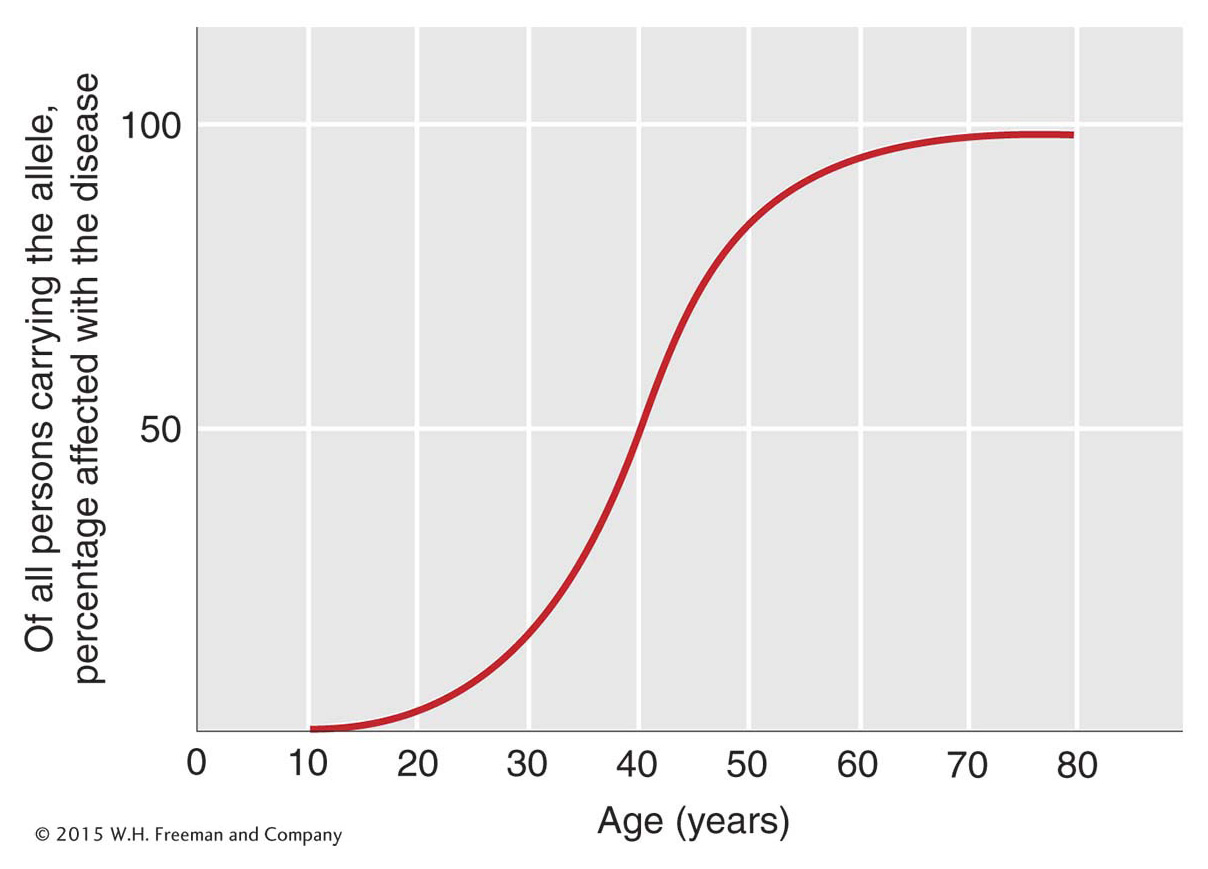

Huntington disease is an example of a disease inherited as a dominant phenotype determined by an allele of a single gene. The phenotype is one of neural degeneration, leading to convulsions and premature death. Folk singer Woody Guthrie suffered from Huntington disease. The disease is rather unusual in that it shows late onset, the symptoms generally not appearing until after the person has reached reproductive age (Figure 2-24). When the disease has been diagnosed in a parent, each child already born knows that he or she has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the allele and the associated disease. This tragic pattern has inspired a great effort to find ways of identifying people who carry the abnormal allele before they experience the onset of the disease. Now there are molecular diagnostics for identifying people who carry the Huntington allele.

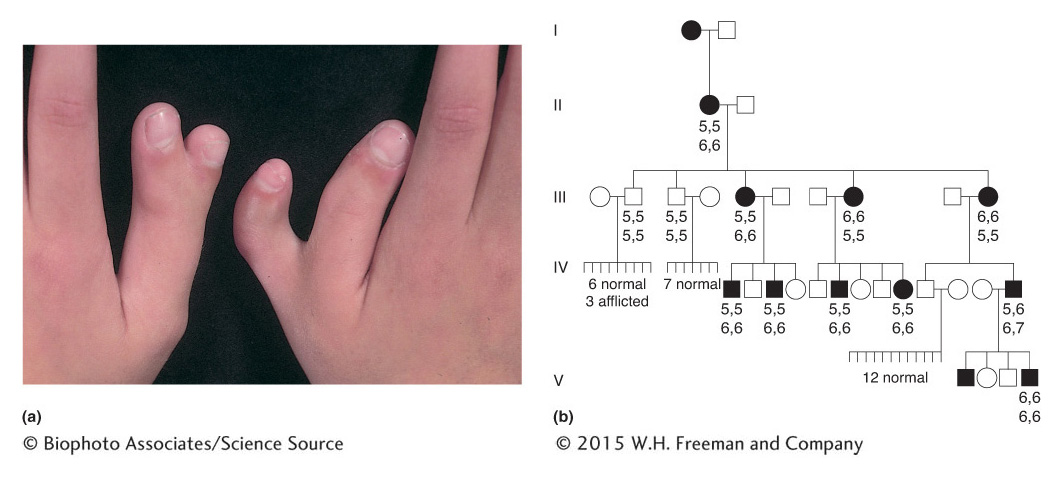

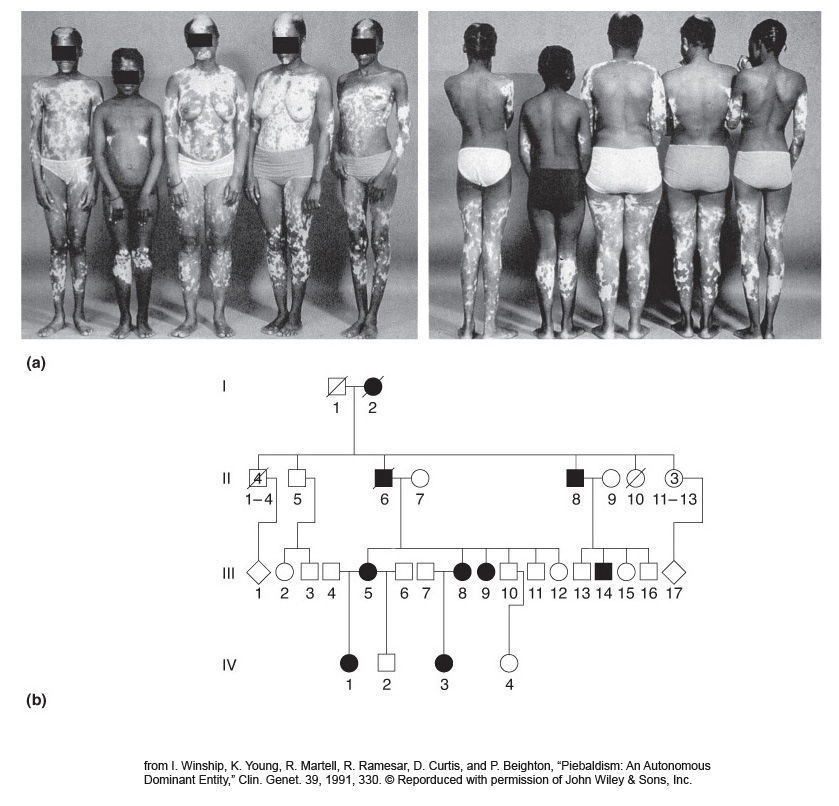

Some other rare dominant conditions are polydactyly (extra digits), shown in Figure 2-25, and piebald spotting, shown in Figure 2-26.

Piebaldism is not a form of albinism; the cells in the light patches have the genetic potential to make melanin, but, because they are not melanocytes, they are not developmentally programmed to do so. In true albinism, the cells lack the potential to make melanin. (Piebaldism is caused by mutations in c-

KEY CONCEPT

Pedigrees of Mendelian autosomal dominant disorders show affected males and females in each generation; they also show affected men and women transmitting the condition to equal proportions of their sons and daughters.Autosomal polymorphisms

The alternative phenotypes of a polymorphism (the morphs) are often inherited as alleles of a single autosomal gene in the standard Mendelian manner. Among the many human examples are the following dimorphisms (with two morphs, the simplest polymorphisms): brown versus blue eyes, pigmented versus blond hair, ability to smell Freesias (a fragrant type of flower) versus inability, widow’s peak versus none, sticky versus dry earwax, and attached versus free earlobes. In each example, the morph determined by the dominant allele is written first.

The interpretation of pedigrees for polymorphisms is somewhat different from that of rare disorders because, by definition, the morphs are common. Let’s look at a pedigree for an interesting human case. Most human populations are dimorphic for the ability to taste the chemical phenylthiocarbamide (PTC); that is, people can either detect it as a foul, bitter taste or—

Polymorphism is an interesting genetic phenomenon. Population geneticists have been surprised at discovering how much polymorphism there is in natural populations of plants and animals generally. Furthermore, even though the genetics of polymorphisms is straightforward, there are very few polymorphisms for which there are satisfactory explanations for the coexistence of the morphs. But polymorphism is rampant at every level of genetic analysis, even at the DNA level; indeed, polymorphisms observed at the DNA level have been invaluable as landmarks to help geneticists find their way around the chromosomes of complex organisms, as will be described in Chapter 4. The population and evolutionary genetics of polymorphisms is considered in Chapters 17 and 19.

KEY CONCEPT

Populations of plants and animals (including humans) are highly polymorphic. Contrasting morphs are often inherited as alleles of a single gene.X-linked recessive disorders

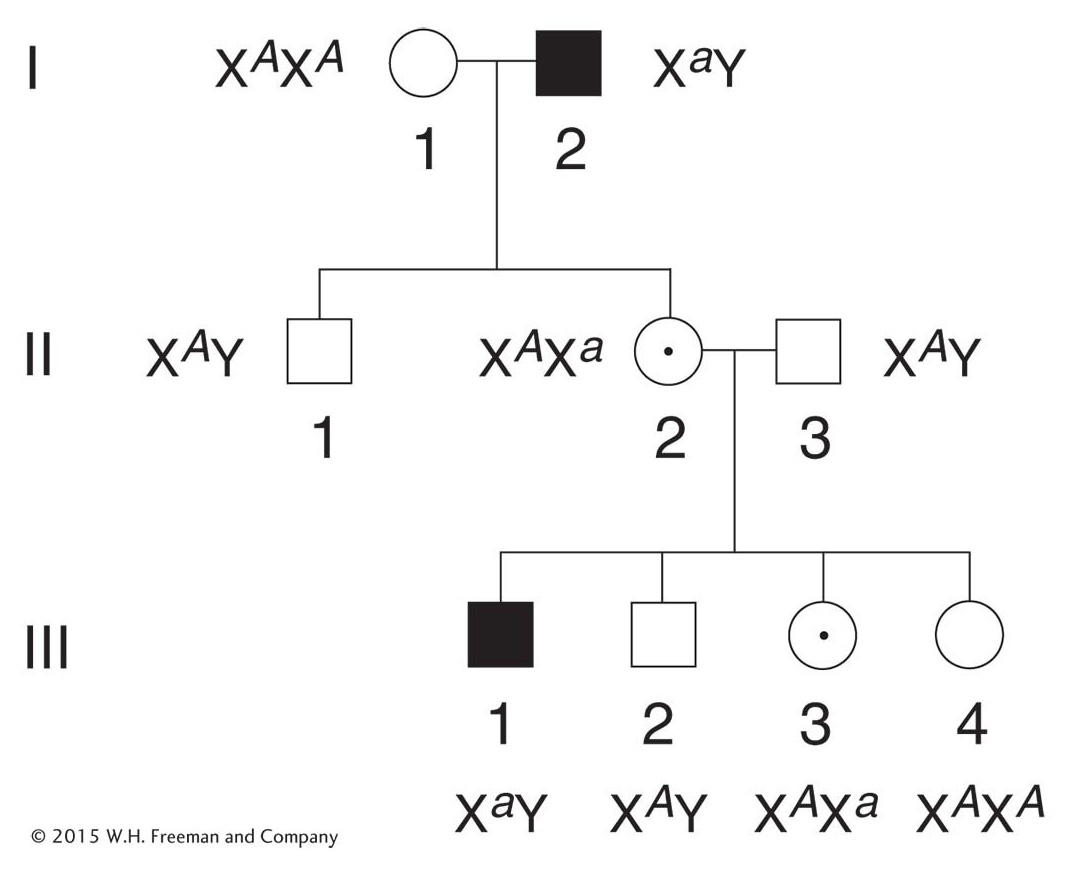

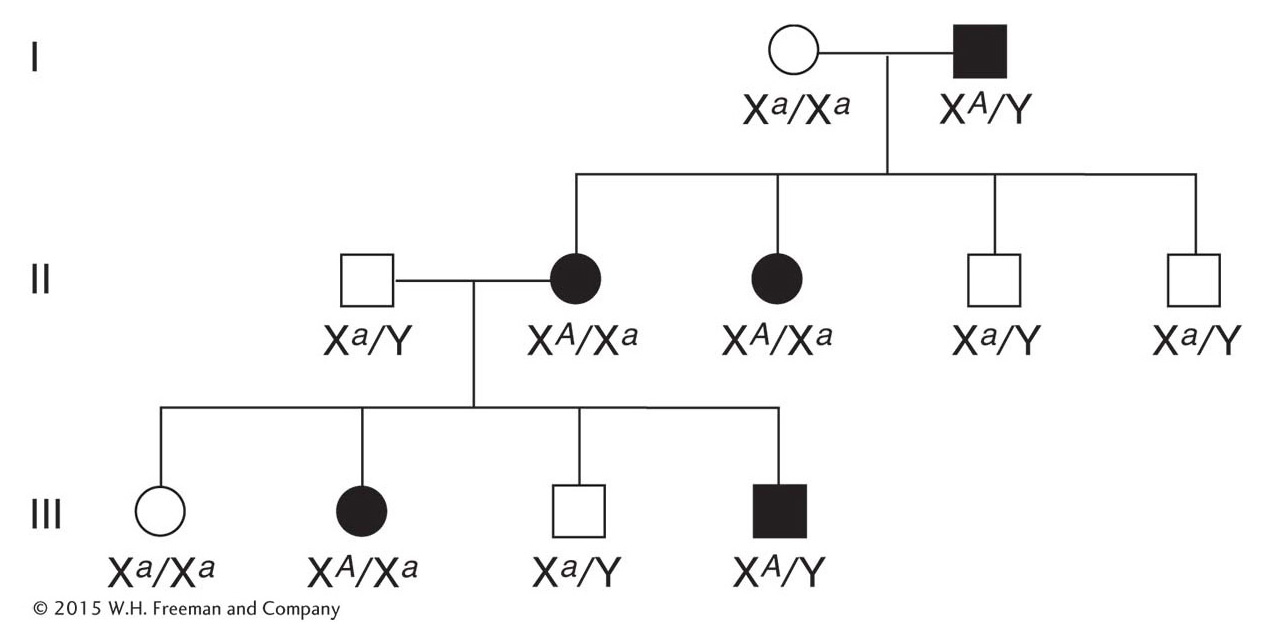

Let’s look at the pedigrees of disorders caused by rare recessive alleles of genes located on the X chromosome. Such pedigrees typically show the following features:

Many more males than females show the rare phenotype under study. The reason is that a female can inherit the genotype only if both her mother and her father bear the allele (for example, XA Xa × Xa Y), whereas a male can inherit the phenotype when only the mother carries the allele (XA Xa × XA Y). If the recessive allele is very rare, almost all persons showing the phenotype are male.

Page 66None of the offspring of an affected male show the phenotype, but all his daughters are “carriers,” who bear the recessive allele masked in the heterozygous condition. In the next generation, half the sons of these carrier daughters show the phenotype (Figure 2-28).

None of the sons of an affected male show the phenotype under study, nor will they pass the condition to their descendants. The reason behind this lack of male-

to- male transmission is that a son obtains his Y chromosome from his father; so he cannot normally inherit the father’s X chromosome, too. Conversely, male- to- male transmission of a disorder is a useful diagnostic for an autosomally inherited condition.

In the pedigree analysis of rare X-

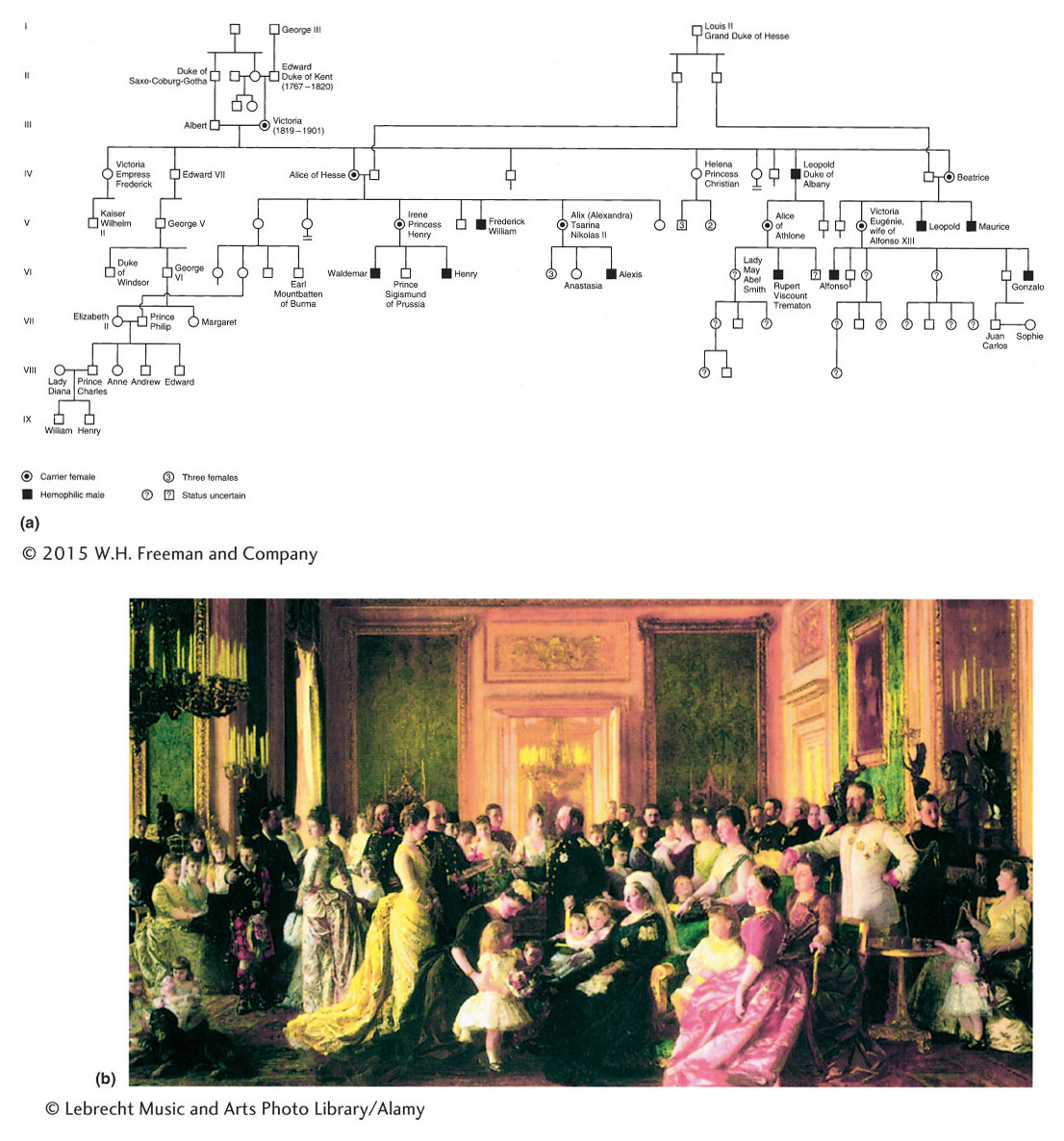

Perhaps the most familiar example of X-

Another familiar example is hemophilia, the failure of blood to clot. Many proteins act in sequence to make blood clot. The most common type of hemophilia is caused by the absence or malfunction of one of these clotting proteins, called factor VIII. A well-

The original hemophilia allele in the pedigree possibly arose spontaneously as a mutation in the reproductive cells of either Queen Victoria’s parents or Queen Victoria herself. However, some have proposed that the origin of the allele was a secret lover of Victoria’s mother. Alexis, the son of the last czar of Russia, inherited the hemophilia allele ultimately from Queen Victoria, who was the grandmother of his mother, Alexandra. Nowadays, hemophilia can be treated medically, but it was formerly a potentially fatal condition. It is interesting to note that the Jewish Talmud contains rules about exemptions to male circumcision clearly showing that the mode of transmission of the disease through unaffected carrier females was well understood in ancient times. For example, one exemption was for the sons of women whose sisters’ sons had bled profusely when they were circumcised. Hence, abnormal bleeding was known to be transmitted through the females of the family but expressed only in their male children.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a fatal X-

A rare X-

X-linked dominant disorders

The inheritance patterns of X-

Affected males pass the condition to all their daughters but to none of their sons.

Affected heterozygous females married to unaffected males pass the condition to half their sons and daughters.

This mode of inheritance is not common. One example is hypophosphatemia, a type of vitamin D–

Y-linked inheritance

Only males inherit genes in the differential region of the human Y chromosome, with fathers transmitting the genes to their sons. The gene that plays a primary role in maleness is the SRY gene, sometimes called the testis-

There have been no convincing cases of nonsexual phenotypic variants associated with the Y chromosome. Hairy ear rims (Figure 2-32) have been proposed as a possibility, although disputed. The phenotype is extremely rare among the populations of most countries but more common among the populations of India. In some families, hairy ear rims have been shown to be transmitted exclusively from fathers to sons.

KEY CONCEPT

Inheritance patterns with an unequal representation of phenotypes in males and females can locate the genes concerned to one of the sex chromosomes.Calculating risks in pedigree analysis

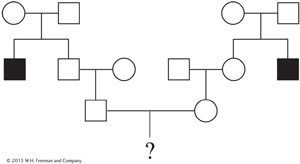

When a disorder with well-

The probability of the couple’s first child having Tay-

The husband’s grandparents must have both been heterozygotes (T/t) because they produced a t/t child (the uncle). Therefore, they effectively constituted a monohybrid cross. The husband’s father could be T/T or T/t, but within the 3/4 of unaffected progeny we know that the relative probabilities of these genotypes must be 1/4 and 1/2, respectively (the expected progeny ratio in a monohybrid cross is

T/T,

T/T,  T/t,

T/t,  t/t. Therefore, there is a 2/3 probability that the father is a heterozygote (two-

t/t. Therefore, there is a 2/3 probability that the father is a heterozygote (two-thirds is the proportion of unaffected progeny who are heterozygotes: that is the ratio of 2/4 to 3/4). The husband’s mother is assumed to be T/T, because she married into the family and disease alleles are generally rare. Thus, if the father is T/t, then the mating with the mother was a cross T/t × T/T and the expected proportions in the progeny (which includes the husband) are

T/T,

T/T,  T/t.

T/t.The overall probability of the husband’s being a heterozygote must be calculated with the use of a statistical rule called the product rule, which states that

The probability of two independent events both occurring is the product of their individual probabilities.

Because gene transmissions in different generations are independent events, we can calculate that the probability of the husband’s being a heterozygote is the probability of his father’s being a heterozygote (2/3) times the probability of his father having a heterozygous son (1/2), which is 2/3 × 1/2 = 1/3.

Likewise, the probability of the wife’s being heterozygous is also 1/3.

If they are both heterozygous (T/t), their mating would be a standard monohybrid cross and so the probability of their having a t/t child is 1/4.

Page 70Overall, the probability of the couple’s having an affected child is the probability of them both being heterozygous and then both transmitting the recessive allele to a child. Again, these events are independent, and so we can calculate the overall probability as 1/3 × 1/3 × 1/4 = 1/36. In other words, there is a 1 in 36 chance of them having a child with Tay-

Sachs disease.

In some Jewish communities, the Tay-