12-6 Reward

Throughout this chapter we have concluded repeatedly that animals engage in a wide range of voluntary behaviors because those behaviors are rewarding. That is, they increase the activity in neural circuits that function to maintain an animal’s contact with certain environmental stimuli, either in the present or in the future. Presumably, the animal perceives the activity of these circuits as pleasant. This would explain why reward can help maintain not only adaptive behaviors such as feeding and sexual activity but also potentially nonadaptive behaviors such as drug addiction. After all, evolution would not have prepared the brain specifically for the eventual development of psychoactive drugs.

Section 7-1 describes how electricalstimulation works both as a treatment and as a research tool.

The first clue to the presence of a reward system in the brain came with an accidental discovery by James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954. They found that rats would perform behaviors such as pressing a bar to administer a brief burst of electrical stimulation to specific sites in their brain. This phenomenon is called intracranial self-

Typically, rats will press a lever hundreds or even thousands of times per hour to obtain this brain stimulation, stopping only when they are exhausted. Why would animals engage in such behavior when it has absolutely no survival value to them or to their species? The simplest explanation is that the brain stimulation is activating the system underlying reward (Wise, 1996).

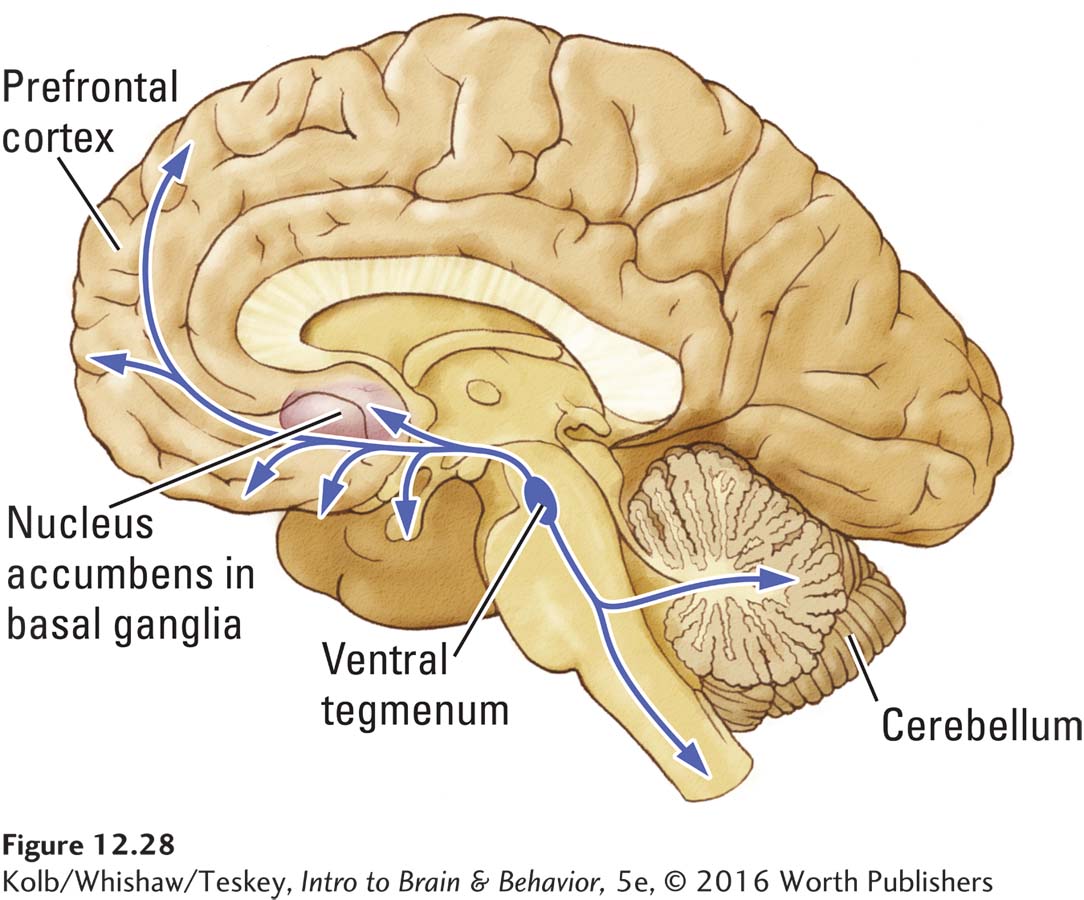

After more than a half-

Neuroscientists have several reasons to believe that the mesolimbic dopamine system is central to circuits mediating reward:

Dopamine release shows a marked increase when animals are engaged in intracranial self-

stimulation. Drugs that enhance dopamine release increase self-

stimulation, whereas drugs that decrease dopamine release also decrease self- stimulation. It seems that the amount of dopamine released somehow determines how rewarding an event is. When animals engage in behaviors such as feeding or sexual activity, dopamine release rapidly increases in locations such as the nucleus accumbens.

Highly addictive drugs such as nicotine and cocaine increase the dopamine level in the nucleus accumbens.

Even opioids appear to affect at least some of an animal’s actions through the dopamine system. Animals quickly learn to press a bar to obtain an opioid injection directly into the midbrain tegmentum or the nucleus accumbens. The same animals do not work to obtain the opioid if the dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic system are inactivated. Apparently, then, animals engage in behaviors that increase dopamine release.

Nor is dopamine the only rewarding compound in the brain. For example, opioid transmitters such as encephalin and dynorphin are also rewarding, as are benzodiazepines.

Robinson and Berridge (2008) propose that reward contains separable psychological components corresponding roughly to wanting, which is often called incentive, and liking, which is equivalent to an evaluation of pleasure. This idea can be applied to discovering why we increase contact with a stimulus such as chocolate.

Robinson and Berridge’s wanting-

Two independent factors are at work: our desire to eat the chocolate (wanting) and the pleasurable effect of eating the chocolate (liking). This distinction is important. If we maintain contact with a certain stimulus because dopamine is released, the question becomes whether the dopamine plays a role in the wanting or the liking aspect of the behavior. Robinson and Berridge propose that wanting and liking processes are mediated by separable neural systems and that dopamine is the transmitter for the wanting. Liking, they hypothesize, entails opioid and benzodiazepine–

According to Robinson and Berridge, wanting and liking are normally two aspects of the same process, so rewards are usually wanted and liked to the same degree. However, it is possible, under certain circumstances, for wanting and liking to change independently.

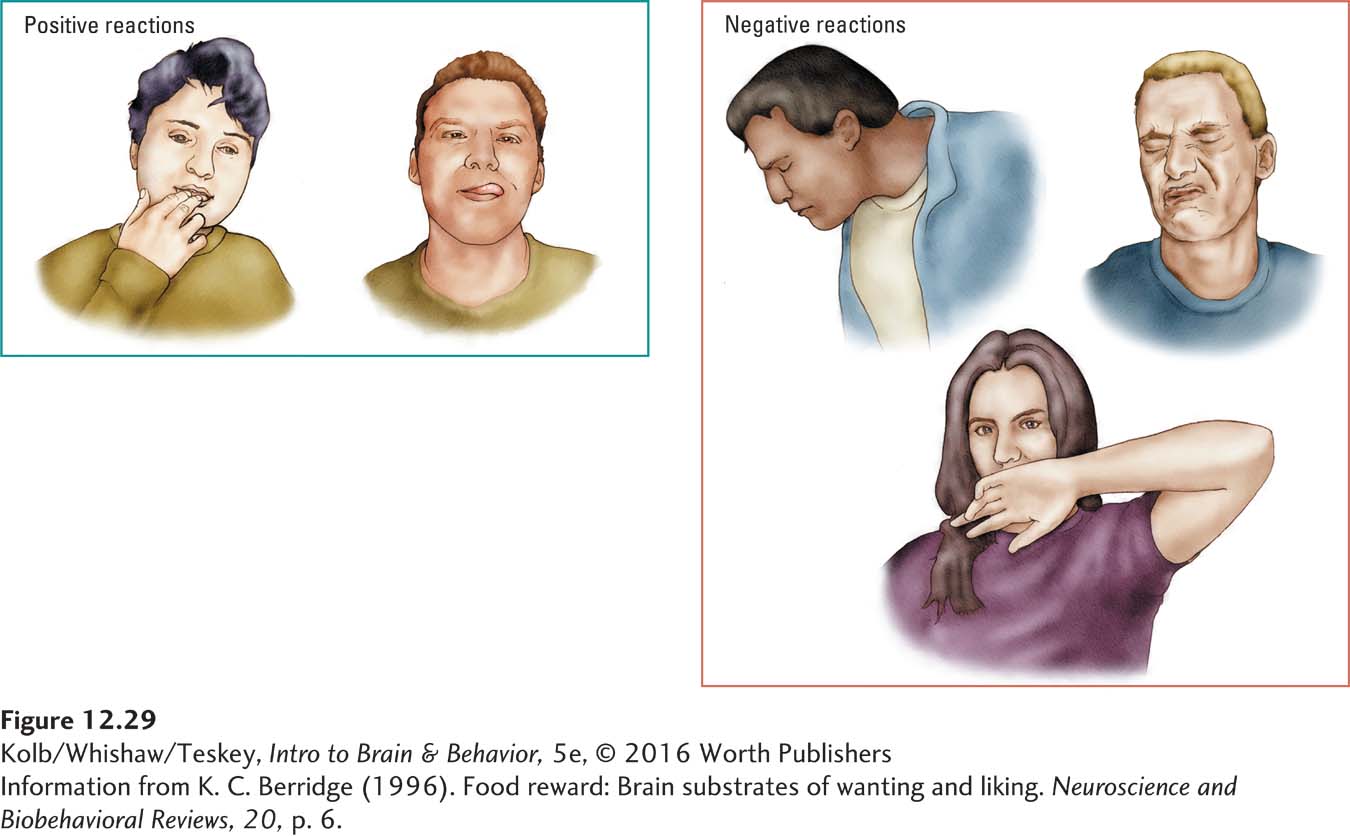

Consider rats with lesions of the ascending dopaminergic pathway to the forebrain. These rats do not eat. Is it simply that they do not desire to eat (a loss of wanting), or has food become aversive to them (a loss of liking)? To find out which factor is at work, the animals’ facial expressions and body movements in response to food can be observed to see how liking is affected. After all, when animals are given various foods to taste, they produce different facial and body reactions, depending on whether they perceive the food as pleasant or aversive.

Among humans, typically when a person tastes something sweet, he or she responds by licking the fingers or the lips, as shown at the left of Figure 12-29. If the taste is unpleasantly salty, say, as shown in the right panel, the reaction is often spitting, grimacing, or wiping the mouth with the back of the hand. Rats, too, show distinctive positive and negative responses to pleasant and unpleasant tastes.

By watching the responses when food is squirted into the mouth of a rat that otherwise refuses to eat, we can tell to what extent a loss of liking is a factor in the animal’s food rejection. Interestingly, rats that do not eat after receiving lesions to the dopamine pathway act as though they still like food.

Now consider a rat with a self-

If the brain stimulation primes eating by evoking pleasurable sensations, we would expect the animal to be more positive in its facial and body reactions to foods when the stimulation is turned on. In fact, the opposite occurs. During stimulation, rats react more aversively to tastes such as sugar and salt than when stimulation is off. Apparently, the stimulation increases wanting but not liking.

Such experiments show that what appears to be a single event—

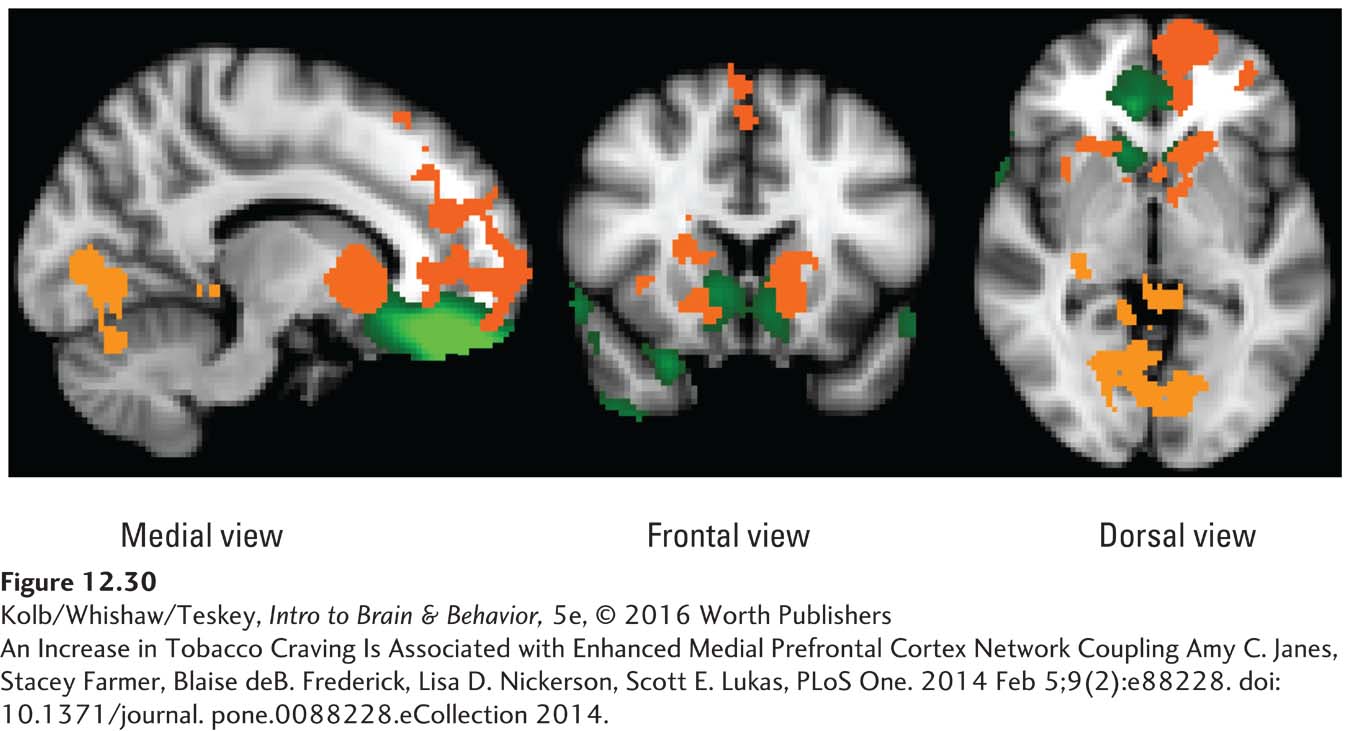

Like the networks underlying perception and memory, the prefrontal and limbic networks underlying reward are diffuse. Amy Janes and her colleagues (2012) used resting-

The general conclusions from these studies and from related studies of gamblers are that neural reward pathways are diffuse and that the pathways’ size and activity are related to the reward’s intensity. The hope is that rs-

12-6 REVIEW

Reward

Before you continue, check your understanding.

Question 1

Animals engage in voluntary behaviors because the behaviors are ______________.

Question 2

Neural circuits maintain contact with rewarding environmental stimuli in the present or in the future through ______________ and ______________ subsystems.

Question 3

The neurotransmitter systems hypothesized to be basic to reward are ______________ , ______________ , and ______________ systems.

Question 4

What is intracranial self-

Answers appear in the Self Test section of the book.