17.4 The 2008 Crisis and Its Aftermath

As we’ve just seen, banking crises have typically been followed by major economic problems. How did the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 compare with this historical experience? The answer, unfortunately, is that history has proved a very good guide: once again, the economic damage from the financial crisis was both large and prolonged. And aftershocks from the crisis continue to shake the world economy today, after Lehman’s 2008 fall.

Severe Crisis, Slow Recovery

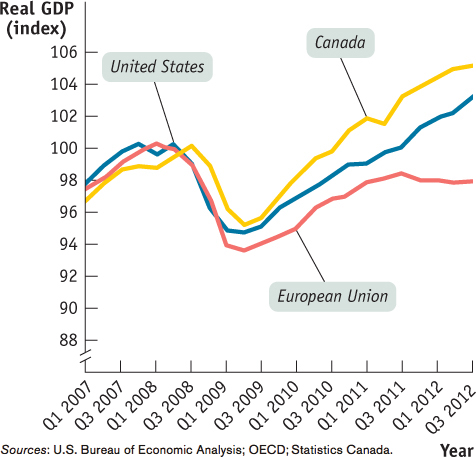

Figure 17-6 compares how the real GDPs of Canada and the two largest economies, the United States and the European Union (EU), fared during the crisis and its aftermath. For ease of comparison, the peak pre-

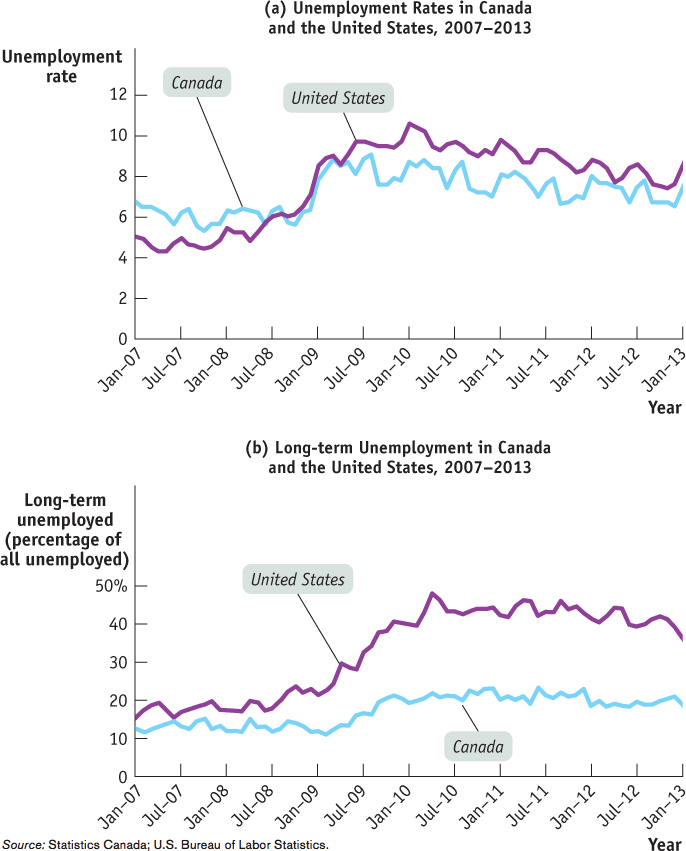

The severe slump and the slow recovery were very bad news for workers, since a healthy job market depends on an economy growing fast enough to accommodate both a growing workforce and rising productivity. Figure 17-7 shows two indicators of unemployment in Canada and the United States—

This outcome was, sad to say, about what one should have expected given the severity of the initial financial shock and the historical experience with such shocks. In fact, in the U.S. experience, unemployment almost exactly matched the average performance of past economies that had suffered major banking disruptions. America, observed Kenneth Rogoff (whose work we cited earlier), was experiencing a “garden variety severe financial crisis.” While Canada’s labour market performed better than that of the United States, Canadian workers still experienced significant suffering even years after the crisis.

Aftershocks in Europe

One important factor bedevilling hopes for recovery was the emergence of special difficulties in several European nations—

The 2008 crisis was caused by problems with private debt, mainly home loans, which then triggered a crisis of confidence in banks. In 2011 and 2012, fears of a second crisis were focused on public debt, specifically the public debts of Southern European countries plus Ireland.

Europe’s troubles first surfaced in Greece, a country with a long history of fiscal irresponsibility. In late 2009, it was revealed that a previous Greek government had understated the size of the budget deficits and the amount of government debt, prompting lenders to refuse further loans to Greece. Other European countries provided emergency loans to the Greek government in return for harsh budget cuts. But these budget cuts depressed the Greek economy, and by late 2011 there was general agreement that Greece could not pay back its debts in full.

By itself, this was probably a manageable shock for the European economy since Greece accounts for less than 3% of European GDP. Unfortunately, foot-

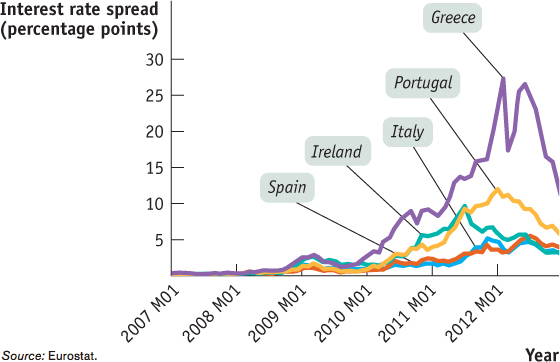

Figure 17-8 shows a measure of pressure on Italy, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece during the 2008 and 2011 crises: the difference between interest rates on 10-year bonds issued by these five nations’ governments and interest rates onGerman debt, which most people consider a safe investment. Because all six countries use the same currency, the euro, these rates would all be the same if the government debt of Italy, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece were considered as safe as German government debt. The rise in “spreads” therefore indicates a growing perception of default risk.

Spain’s fiscal problems were mainly fallout from the 2008 crisis. Before that crisis, Spain seemed to be in very good fiscal condition, with low debt and a budget surplus. However, Spain, like Ireland, had a huge housing bubble between 2000 and 2007. When the bubble burst, the Spanish economy fell into a deep slump, depressing tax receipts and causing large budget deficits. At the same time, there were worries that the Spanish government might eventually have to spend large amounts bailing out banks. As a result, investors began worrying about the solvency of the Spanish government and a possible default, driving up interest rates.

Italy’s case was somewhat different. Italy has long had high levels of public debt as a percentage of GDP, but it has not run large deficits in recent years; as late as the spring of 2010 its fiscal position looked fairly stable. At that point, however, investors began to have doubts about the Italian government’s solvency, in part because in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis the Italian economy was growing very slowly—

At the time of writing, Greece had defaulted on its government bonds twice in 2012; Spanish unemployment had hit 26%, with youth unemployment close to 56%; and it was unclear how much worse the European situation would get. But Europe’s difficulties reinforced the sense that the damage from the 2008 financial crisis was by no means over.

The Stimulus–Austerity Debate

The persistence of economic difficulties after the 2008 financial crisis led to fierce debates about appropriate policy responses. Broadly speaking, economists and policy-

The proponents of more stimulus pointed to the continuing poor performance of major economies, arguing that the combination of high unemployment and relatively low inflation clearly pointed to the need for expansionary policies. And since monetary policy was limited by the zero bound on interest rates, stimulus proponents advocated expansionary fiscal policy to fill the gap.

The austerity camp took a very different view. Strongly influenced by the solvency troubles of Greece, Ireland, Spain, and Italy, they argued that the common source of all the problems were high levels of government deficits and debts. In their view, countries like the United States that continued to run large government deficits several years after the 2008 crisis were at risk of suffering a similar loss of investor confidence in their ability to repay their debts. Moreover, austerity advocates claimed that cuts in government spending would not actually be contractionary because they would improve investor confidence and keep interest rates on government debt low.

Each side of the debate argued that recent experience refuted the other side’s claims. Austerity proponents argued that the persistence of high unemployment despite the fiscal stimulus programs adopted by Canada, the United States, and other major economies in 2009 showed that stimulus doesn’t work. Stimulus advocates argued that these programs were simply inadequate in size, pointing out that many economists had warned of their inadequacy from the start. Stimulus advocates further argued that warnings about the dangers of deficits were overblown, that far from rising, borrowing costs for Canada, Japan, the United States, and Britain—

At the time of writing, neither side was giving much ground. Clearly, any resolution of the debate would hinge on future economic developments and how they were interpreted.

The Lesson of the Post-Crisis Slump

Almost all major economies had great difficulty dealing with the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis—

Clearly, then, the best way to avoid the terrible problems that arise after a financial crisis is not to have a crisis in the first place. How can you do that? In part, one might hope, through better regulation of financial institutions. We turn next to attempts at regulatory reform.

AUSTERITY BRITAIN

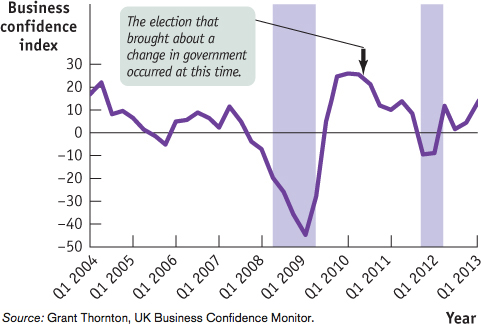

An election in May 2010 led to a shift in power in Britain, with a Labour Party government replaced by a coalition dominated by the Conservative Party under the new prime minister, David Cameron. The new government was firmly committed to the austerity side of the great post-

Unlike Greece or Ireland, Britain wasn’t under any immediate pressure to slash its budget deficit. Like the Canadian government, the British government was still able to borrow cheaply despite its large deficit. And the British economy was, if anything, even more depressed than the Canadian one, with fewer signs of recovery. The Cameron government believed, however, that preemptive cuts in public spending combined with some tax increases were necessary to preserve investor confidence and also that such cuts could boost the economy by improving confidence.

How have these policies performed? As of 2012 and early 2013, the experiment in austerity had yielded disappointing results. British economic growth was weak—

Quick Review

Economic damage from the financial crisis of 2008 was both large and prolonged. Aftershocks from the crisis continue to shake the world economy.

Like Canada, the world’s two largest economies, in the United States and the European Union, suffered severe downturns, shrinking more than 4%, followed by relatively slow recoveries. The severe slump and the slow recovery were very bad news for workers.

The persistence of economic difficulties after the 2008 financial crisis led to severe solvency concerns for several European countries. A fierce debate erupted over whether fiscal stimulus or fiscal austerity was the right policy prescription.

Check Your Understanding 17-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 17-4

In November 2011, the government of France announced that it was reducing its forecast for economic growth in 2012. It was also reducing its estimates of tax revenue for 2012, since a weaker economy would mean smaller tax receipts. To offset the effect of lower revenue on the budget deficit, the government also announced a new package of tax increases and spending cuts. Which side of the stimulus–

austerity debate was France taking?

According to standard macroeconomics, a government should adopt expansionary policies to increase aggregate demand to address an economic slump. France, however, did just the opposite, responding to a weaker economy with a contractionary fiscal policy that would make the economy even weaker. This shows that the French government had adopted the austerity view, believing that it was more important to try to assure markets of its solvency than to support the economy.