Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 (1808)

Beethoven composed his Fifth Symphony together with his Sixth (Pastoral) for one of the rare concerts in which he was able to showcase his own works. This concert, in December 1808, was a huge success, even though it ran on for five hours and the heating in the hall failed.

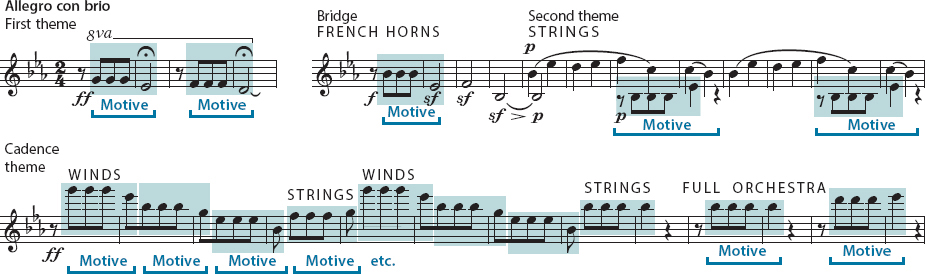

First Movement (Allegro con brio) Motivic consistency, as we have said, is a special feature of Beethoven’s work. The first movement of the Fifth Symphony is famously saturated by a single rhythmic motive, ![]() . This motive forms the first theme in the exposition and it initiates the bridge. It is even heard as a subdued background to the lyrical, contrasting second theme; and it emerges again at full force in the cadence material:

. This motive forms the first theme in the exposition and it initiates the bridge. It is even heard as a subdued background to the lyrical, contrasting second theme; and it emerges again at full force in the cadence material:

The motive then expands further in the development section and continues growing in the long coda.

How is this different from Classical motivic technique? In such works as Mozart’s Symphony No. 40, a single motive is likewise developed with consistency and a sense of growth. But Beethoven’s use of the same device gives the Fifth Symphony its particular gripping urgency. The difference is not in the basic technique but in the way it is being used — in the expressive intensity it is made to serve. It is a Classical device used for non-

Exposition The movement begins with an arresting presentation of the first theme, in the key of C minor (shown above). The meter is disrupted by two fermatas (a fermata ![]() indicates an indefinite hold of the note it comes over). These give the music an improvisational, primal quality, like a great shout. Even after the theme surges on and seems to be picking up momentum, it is halted by a new fermata, making three fermatas in all.

indicates an indefinite hold of the note it comes over). These give the music an improvisational, primal quality, like a great shout. Even after the theme surges on and seems to be picking up momentum, it is halted by a new fermata, making three fermatas in all.

The horn-

The second theme introduces a new gentle mood, despite the main motive rumbling away below it. But this mood soon fades — Beethoven seems to brush it aside impatiently. The main motive returns in a stormy cadence passage, which comes to a satisfying, complete stop. The exposition is repeated.

Development The development section starts with a new eruption, as the first theme makes a (very clear) modulation, a modulation that returns to the minor mode. There is yet another fermata. It sounds like the crack of doom.

For a time the first theme (or, rather, its continuation) is developed, leading to a climax when the ![]() rhythm multiplies itself furiously, as shown to the right. Next comes the bridge theme, modulating through one key after another. Suddenly the two middle pitches of the bridge theme are isolated and echoed between high wind instruments and lower strings. This process is called fragmentation (for an example from Mozart, see page 166). The two-

rhythm multiplies itself furiously, as shown to the right. Next comes the bridge theme, modulating through one key after another. Suddenly the two middle pitches of the bridge theme are isolated and echoed between high wind instruments and lower strings. This process is called fragmentation (for an example from Mozart, see page 166). The two-

Learning to Appreciate Beethoven, Part 1

“Went to a German charitable concert [the American premiere of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony]. . . . The music was good, very well selected and excellently well performed, as far as I could judge. The crack piece, though, was the last, Beethoven’s Sinfonia in C minor. It was generally unintelligible to me, except the Andante.”

Diary of a New York music lover, 1841

Beethoven is famous for the tension he builds up in retransitions, the sections in sonata form that prepare for the recapitulations (see page 164). In the Fifth Symphony, the hush at this point becomes almost unbearable. Finally the whole orchestra seems to grab and shake the listener by the lapels, shouting the main motive again and again until the first theme settles out in the original tonic key.

Recapitulation The exposition version of the main theme was interrupted by three fermatas. Now, in the recapitulation, the third fermata is filled by a slow, expressive passage for solo oboe, a sort of cadenza in free rhythm. This extraordinary moment provides a brief rest from the continuing rhythmic drive. Otherwise the recapitulation stays very close to the exposition — a clear testimony to Beethoven’s Classical allegiance.

Coda On the other hand, the action-

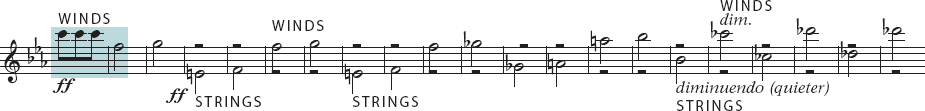

In the exposition, we recall, the stormy cadence passage was defused by a satisfying Classical cadence and a complete stop. At the end of the recapitulation, the parallel passage seems to reject any such easy solution. Instead a new contrapuntal idea appears, with French horns below and strings above:

In the melody for French horns we hear the four main-![]() Then the two middle notes of this melody are emphasized by a long downward sequence.

Then the two middle notes of this melody are emphasized by a long downward sequence.

The sequence evolves into a sort of grim minor-

Learning to Appreciate Beethoven, Part 2

“I expected to enjoy that Symphony [Beethoven’s Fifth], but I did not suppose it possible that it could be the transcendent affair it is. I’ve heard it twice before, and how I could have passed by unnoticed so many magnificent points — appreciate the spirit of the composition so feebly and unworthily — I can’t imagine.”

Diary of the same New Yorker, 1844

The Remaining Movements The defiant-

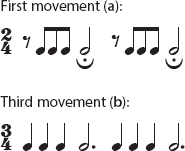

The later movements of the Fifth Symphony feel like responses to — and, ultimately, a resolution of — all the tension Beethoven had summoned up in the first movement. We are never allowed to forget the first movement and its mood, not until the very end of the symphony, mainly because a form of the first movement’s rhythmic motive, ![]() , is heard in each of the later movements. This motive always stirs uneasy recollections. Furthermore, the later movements all refer to the key of the first movement. Whenever this key returns in its original minor mode (C minor), it inevitably recalls the struggle that Beethoven is said to have associated with “Fate knocking at the door.” When it returns in the major mode (C major), it signifies (or foretells) the ultimate resolution of all that tension — the triumph over Fate.

, is heard in each of the later movements. This motive always stirs uneasy recollections. Furthermore, the later movements all refer to the key of the first movement. Whenever this key returns in its original minor mode (C minor), it inevitably recalls the struggle that Beethoven is said to have associated with “Fate knocking at the door.” When it returns in the major mode (C major), it signifies (or foretells) the ultimate resolution of all that tension — the triumph over Fate.

Don’t worry about recognizing C major or distinguishing it from any other major-

A special abbreviated Listening Chart for the entire symphony is provided on page 213. All the C-

Second Movement (Andante con moto) The first hint of Beethoven’s master plan comes early in the slow movement, after the cellos have begun with a graceful theme, which is rounded off by repeated cadences. A second graceful theme begins, but is soon derailed by a grinding modulation — to C major, where the second theme starts again. Blared out by the trumpets, ff, it’s no longer graceful — it would sound like a brutal fanfare if it didn’t fade almost immediately into a mysterious passage where the ![]() rhythm of the first movement sounds quietly. Beethoven is not ready to resolve the C-

rhythm of the first movement sounds quietly. Beethoven is not ready to resolve the C-

Third Movement (Allegro) This movement, in 3/4 time, is one of Beethoven’s great scherzos (though the composer did not label it as such, probably because its form is so free). There are two features of the smooth, quiet opening theme (a) that immediately recall the mood of the first movement — but in a more muted, apprehensive form. One is the key, C minor. The other is the interruption of the meter by fermatas.

Then a very forceful second theme (b), played by the French horns, recalls in its turn the first movement’s rhythmic motive. The two themes alternate and modulate restlessly, until the second makes a final-

When now a bustling and somewhat humorous fugal section starts in the major mode — in C major — we may recognize a vestige of the old minuet-

After this, the opening minor-

Fourth Movement (Allegro) The point of this reorchestration appears when the section does not reach a cadence but runs into a truly uncanny transition, with timpani tapping out the rhythm of b — the original DA–

Minor mode cedes to major, pp to ff, mystery to clarity; the arrival of this symphony’s last movement, after the continuous transition from the scherzo, has the literal effect of triumph over some sort of adversity. This last movement brings in three trombones for the first time in the symphony. (They must have really awakened the freezing listeners at that original 1808 concert.)

The march makes a splendid first theme of a sonata-

Then, at the end of the development, Beethoven offers another example of his inspired manipulation of musical form. The second theme (b) of the previous movement, the scherzo, comes back quietly once again, a complete surprise in these surroundings (there is even a change from the 4/4 meter of the march back to 3/4). This theme now sounds neither forceful nor mysterious, as it did in the scherzo, but rather like a dim memory. Perhaps it has come back to remind us that the battle has been won.

All that remains is a great C-