Claude Debussy, Clouds, from Three Nocturnes (1899)

Debussy’s Three Nocturnes, like most of his orchestral works, might be described as impressionist symphonic poems, though they have titles only, not narrative programs. They suggest various scenes without attempting to illustrate them explicitly.

“The title ‘Nocturnes’ should be taken here in a more general and especially in a more decorative sense. . . . Clouds: the unchanging aspect of the sky, the slow, melancholy motion of the clouds, fading away into agonized grey tones, gently tinged with white.”

Claude Debussy

The word nocturne evokes a nighttime scene, the great examples before Debussy being the piano nocturnes of Chopin (see page 245). But in fact Debussy’s reference was to famous atmospheric paintings by an artist who was close to the impressionists, James McNeill Whistler (see page 314). The first of the nocturnes, Clouds, is a pure nature picture, the least nocturnal of the three. The second, Festivals, depicts mysterious nighttime fairs and parades. The third nocturne, Sirens, includes a women’s chorus along with the orchestra, singing not words but vowels and adding an unforgettable timbre to the usual orchestra. The women’s voices evoke the legendary sea maidens of the title, who tempt lonely sailors and pull them into the deep.

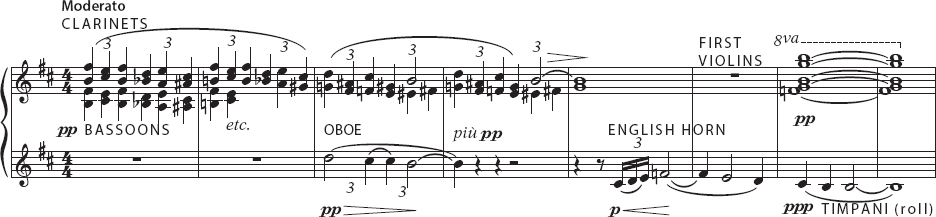

In Clouds, we first hear a quiet series of chords, played by clarinets and bassoons, that circles back on itself repeatedly. The chords seem to suggest great cumulus clouds, moving slowly and silently across the sky.

As a theme, however, these chords do not function conventionally. They make no strong declarations and lead nowhere definitive. This is also true of the next motive, introduced by the English horn — a haunting motive that occurs many times in Clouds, with hardly any change. (It is built on an octatonic scale; see page 310.) Yet even this muted gesture, with its vague rhythm and its fading conclusion, seems sufficient to exhaust the composition and bring it to a near halt, over a barely audible drumroll:

After this near stop, the “cloud” music begins again, leading this time to a downward passage of remarkably gentle, murmuring chords in the strings. These chords all share the same rich, complex structure. Their pitches slip downward, moving parallel to one another without establishing a clear sense of tonality. This use of parallel chords is one of Debussy’s most famous innovations.

Clouds might be said to fall into an A B A′ form — but only in a very approximate way. Debussy shrinks from clear formal outlines; the musical form here is much more fluid than A B A structures observed in earlier music. Such fluidity is something to bear in mind when following Clouds and other avant-

In the A section of Clouds, the return of the cloud theme after a more active, restless passage suggests an internal a b a′ pattern as well. The next idea, B, sounds at first like a meditative epilogue to A; it is built on a pentatonic scale (see page 310). But when the little pentatonic tune is repeated several times, it begins to feel like a substantial section of contrast. The return, A′, is really just a reference to some of A’s material, notably the English-