Alban Berg (1885–1935), Wozzeck (1923)

After Schoenberg, the most powerful exponent of expressionism in music was his student Alban Berg. Berg’s opera Wozzeck, first conceived during World War I, was completed in 1923. In general plan, this opera can be described as Wagnerian, in that it depends on musical continuity carried by the orchestra. It uses leitmotivs and contains no arias. In more specific matters, its musical style owes much to Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire.

Berg set a remarkable fragmentary play by the German dramatist Georg Büchner, a half-

Franz Wozzeck is an inarticulate and impoverished soldier, the lowest cog in the military machine. He is troubled by visions and tormented for no apparent reason by his captain and by the regimental doctor. Wozzeck’s lover, Marie, sleeps with a drum major, who beats Wozzeck up when he objects. Finally Wozzeck murders Marie, goes mad, and drowns himself. Büchner’s play provided the perfect material for an expressionist opera.

Act III; Interlude after scene ii Scene ii is the murder scene. When Wozzeck stabs Marie, she screams, and all the leitmotivs associated with her blare away in the orchestra, as if all the events of her lifetime were flashing before her eyes.

A blackout follows, and the stark interlude between the scenes consists of a single pitch played by the orchestra in two gut-

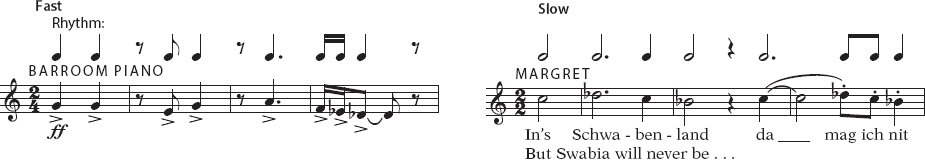

Scene iii The lights snap on again. In a sordid tavern, Wozzeck gulps a drink and seeks consolation with Marie’s friend Margret. Berg’s idea of a ragtime piano opens the scene — one of many signs that European music of the 1920s had woken up to American influences. But it is a distorted, dissonant ragtime, heard through the ears of someone on the verge of a breakdown.

The music is disjointed, confused, shocking. When Margret gets up on the piano and sings a song, her song is distorted, too:

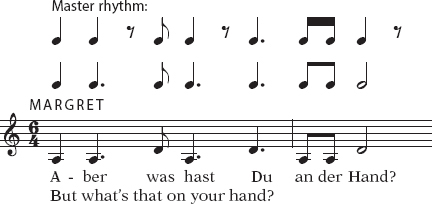

Suddenly she notices blood on Wozzeck’s hand. It smells like human blood, she says. In a dreadful climax to the scene, the apprentices and street girls in the inn come out of the shadows and close in on Wozzeck. He manages to escape during another blackout, as a new orchestral interlude surges frantically and furiously.

The whole of scene iii is built on a single short rhythm, repeated over and over again with only slight modifications — but presented in many different tempos. This twitching “master rhythm” is marked above the two previous examples, first at a fast tempo, then at a slow one; we first heard it in the timpani in the interlude between scenes ii and iii. Another obvious instance comes when Margret first notices the blood:

Here is yet another kind of ostinato — very different from Stravinsky’s (see page 317) or Schoenberg’s in the song “Night” (see page 322). Even though this master rhythm may elude the listener in a good many of its appearances, its hypnotic effect contributes powerfully to the sense of nightmare and fixation.

Scene iv Fatefully, Wozzeck returns to the pond where he murdered Marie. The orchestra engages in some nature illustration; we can even hear frogs croaking around the pond. Wozzeck’s mind has quite cracked. He shrieks for the knife (in powerful Sprechstimme reminiscent of Pierrot lunaire: see page 321), discovers the corpse, and sees the blood-

At this point, his principal tormenters walk by. The captain and the doctor hear the macabre orchestral gurgles and understand that someone is drowning, but like people watching a mugging on a crowded city street, they make no move to help. “Let’s get away! Come quickly!” says the terrified captain — in plain, naturalistic speech, rather than the Sprechstimme used by Wozzeck.

In the blackout after this scene, emotional music wells up in the orchestra, mourning for Wozzeck, Marie, and humanity at large. Here Berg adopts and even surpasses the late Romantic style of Gustav Mahler. Anguished leitmotivs from earlier in the opera, mainly in the brass, surge into a great climax, then subside.

Scene v Berg (following Büchner) has yet another turn of the knife waiting for us in the opera’s final scene. Some children who are playing with Wozzeck’s little son run off to view his mother’s newly discovered corpse. Uncomprehending, he follows them. The icy sweetness of the music here is as stunning as the violent music of the tavern scene and the weird pond music. In turning Büchner’s visionary play fragment into an expressionist opera, Berg created one of the great modernist theater pieces of the twentieth century.

LISTEN

Berg, Wozzeck, Act III, scenes iii and iv

LISTEN

Scene iii: A tavern

LISTEN

Scene iv: A pond in a wood

| SCENE iii: A tavern | |||

| 0:28 | Wozzeck: | Tanzt Alle; tanzt nur zu, springt, schwitzt und stinkt, es holt Euch doch noch einmal der Teufel! |

Dance, everyone! Go on, dance, sweat and stink, the devil will get you in the end. (Gulps down a glass of wine) (Shouts above the pianist:) |

|

Es ritten drei Reiter wohl an den Rhein, Bei einer Frau Wirtin da kehrten sie ein. Mein Wein ist gut, mein Bier ist klar, Mein Töchterlein liegt auf der . . . |

Three horsemen rode along the Rhine, They came to an inn and they asked for wine. The wine was fine, the beer was clear, The innkeeper’s daughter . . . |

||

| 0:58 | Wozzeck: |

Verdammt! Komm, Margret! Komm, setzt dich her, Margret! Margret, Du bist so heiss. . . . Wart’ nur, wirst auch kalt werden! Kannst nicht singen? |

Hell! Come on, Margret! (Dances with her) Come and sit down, Margret! Margret, you’re hot! Wait, you too will be cold! Can’t you sing? (She sings:) |

| 1:36 | Margret: |

In’s Schwabenland, da mag ich nit, Und lange Kleider trag ich nit. Denn lange Kleider, spitze Schuh, Die kommen keiner Dienstmagd zu. |

But Swabia will never be The land that I shall want to choose, For silken dresses, spike- Are not for servant girls like me. |

| Wozzeck: | Nein! keine Schuh, man kann auchblossfüssig in die Höll’ geh’n! Ichmöcht heut raufen, raufen. . . . | No shoes! You can go to hell just as well barefoot! I’m feeling like a fight today! | |

| 2:22 | Margret: | Aber was hast Du an der Hand? | But what’s that on your hand? |

| Wozzeck: | Ich? Ich? | Me? My hand? | |

| Margret: | Rot! Blut! | Red! Blood! | |

| Wozzeck: | Blut? Blut? | Blood? Blood? (People gather around.) | |

| Margret: | Freilich . . . Blut! | Yes, it is blood! | |

| Wozzeck: | Ich glaub’, ich hab’ mich geschnitten, da an der rechten Hand. . . . | I think I cut myself, on my hand. . . . | |

| Margret: | Wie kommt’s denn zum Ellenbogen? | How’d it get right up to the elbow, then? | |

| Wozzeck: | Ich hab’s daran abgewischt. | I wiped it off there. . . . | |

| Apprentices: | Mit der rechten Hand am rechten Arm? | Your right hand on your right arm? | |

| Wozzeck: | Was wollt Ihr? Was geht’s Euch an? | What do you want? What’s it to you? | |

| Margret: | Puh! Puh! Da stinkt’s nach Menschenblut! | Gross! It stinks of human blood! (curtain) | |

| Confusion. The people in the tavern crowd around Wozzeck, accusing him. Wozzeck shouts back at them and escapes. | |||

| SCENE iv: A pond in a wood | |||

| 0:00 | Wozzeck: | Das Messer? Wo ist das Messer? Ich hab’s dagelassen . . . Näher, noch näher. Mir graut’s! Da regtsich was. Still! Alles still und tod . . . Mörder! Mörder! Ha! Daruft’s! Nein, ich selbst. | The knife! Where is the knife? I left it there, around here somewhere. I’m scared! Something’s moving. Silence. Everything silent and dead . . . Murderer! Murderer! Ah, someone called! No, it was just me. |

| Marie! Marie! Was hast Du für eine rote Schnur um den Hals? Hast Dir das rote Halsband verdient, wie die Ohrringlein, mit Deiner Sünde? Was hangen Dir die schwartzen Haare so wild? | Marie, Marie! What’s that red cord around your neck? A red necklace, payment for your sins, like the earrings? Why is your dark hair so wild? | ||

| 1:12 | Mörder! Mörder! Sie werden nach mir suchen. . . . Das Messer verrätmich! Da, da ist’s! | Murderer! Murderer! They will come look for me. . . . The knife will betray me! Here, here it is. | |

| So! da hinunter! Es taucht ins dunkle Wasser wie ein Stein. Aber der Mond verrät mich . . . der Mond ist blutig. Will denn die ganze Welt es ausplaudern?! — Das Messer, es liegt zu weit vorn, sie finden’s beim Baden oder wenn sie nach Muscheln tauchen. | There! Sink to the bottom! It plunges into the dark water like a stone. But the moon will betray me. . . . The moon is bloody. Is the whole world going to betray me? The knife is too near the edge — they’ll find it when they’re swimming or gathering mussels. | ||

| Ich find’s nicht . . . Aber ich muss mich waschen. Ich bin blutig. Da ein Fleck . . . und noch einer. | I can’t find it. But I have to get washed. There’s blood on me. Here’s one spot . . . here’s another. . . . | ||

| Weh! Weh! Ich wasche mich mit Blut! Das Wasser ist Blut . . . Blut. . . . | Oh, woe! I am washing myself in blood! The water is blood . . . blood. . . .(drowns) | ||

| 3:01 | Captain: | Halt! | Wait! |

| Doctor: | Hören Sie? Dort! | Don’t you hear? There! | |

| Captain: | Jesus! Das war ein Ton! | Jesus! What a sound! | |

| Doctor: | Ja, dort. | Yes, there. | |

| Captain: | Es ist das Wasser im Teich. Das Wasser ruft. Es ist schon lange Niemand entrunken. Kommen Sie, Doktor! Es ist nicht gut zu hören. | It’s the water in the pond, the water is calling. It’s been a long time since anyone drowned. Come away, Doctor! This is not good to hear. | |

| Doctor: | Das stöhnt . . . als stürbe ein Mensch. Da ertrinkt Jemand! | There’s a groan, as though someone were dying. Somebody’s drowning! | |

| Captain: |

Unheimlich! Der Mond rot und die Nebel grau. Hören Sie? . . . Jetzt wieder das Ächzen. |

It’s weird! the red moon, the gray mist. Now do you hear? . . . That moaning again. |

|

| Doctor: | Stiller, . . . jetzt ganz still. | It’s getting quieter — now it’s stopped. | |

| Captain: | Kommen Sie! Kommen Sie schnell! | Let’s get away! Come quickly! (curtain) | |

| 4:30 | ORCHESTRAL MUSIC (Lament) | ||

|

Berg, Wozzeck. © 1926 by Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. English translation © 1952 by Alfred A. Kalmus, London Copyright © renewed. All rights reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors, U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. |

|||