All Transmembrane Proteins and Glycolipids Are Asymmetrically Oriented in the Bilayer

Every type of transmembrane protein has a specific orientation, known as its topology, with respect to the membrane faces. Its cytosolic segments always face the cytosol, and its exoplasmic segments always face the opposite side of the membrane. This asymmetry in protein orientation gives the two membrane faces their different properties. The orientations of different types of transmembrane proteins are established during their synthesis, as we will see in Chapter 13. Membrane proteins have never been observed to flip-

Many transmembrane proteins contain carbohydrate chains covalently linked to serine, threonine, or asparagine side chains of the polypeptide. Such transmembrane glycoproteins are always oriented so that all the carbohydrate chains are in the exoplasmic domain (see Figure 7-14 for the example of glycophorin A). Likewise, glycolipids, in which a carbohydrate chain is attached to the glycerol or sphingosine backbone of a membrane lipid, are always located in the exoplasmic leaflet, with the carbohydrate chain protruding from the membrane surface. The biosynthetic basis for the asymmetric glycosylation of proteins is described in Chapter 14. Both glycoproteins and glycolipids are especially abundant in the plasma membranes of eukaryotic cells and in the membranes of the intracellular compartments that establish the secretory and endocytic pathways; they are absent from the inner mitochondrial membrane, chloroplast lamellae, and several other intracellular membranes. Because the carbohydrate chains of glycoproteins and glycolipids in the plasma membrane extend into the extracellular space, they are available to interact with components of the extracellular matrix as well as with lectins (proteins that bind specific sugars), growth factors, and antibodies.

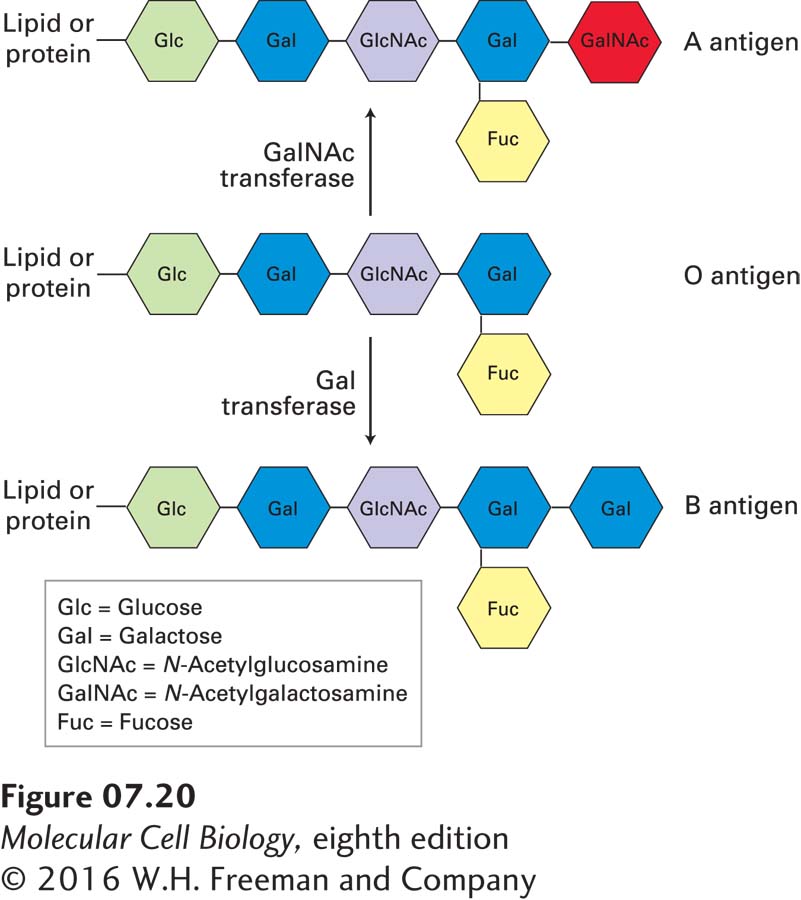

![]() One important consequence of interactions involving membrane glycoproteins and glycolipids is illustrated by the ABO blood-

One important consequence of interactions involving membrane glycoproteins and glycolipids is illustrated by the ABO blood-

Page 290

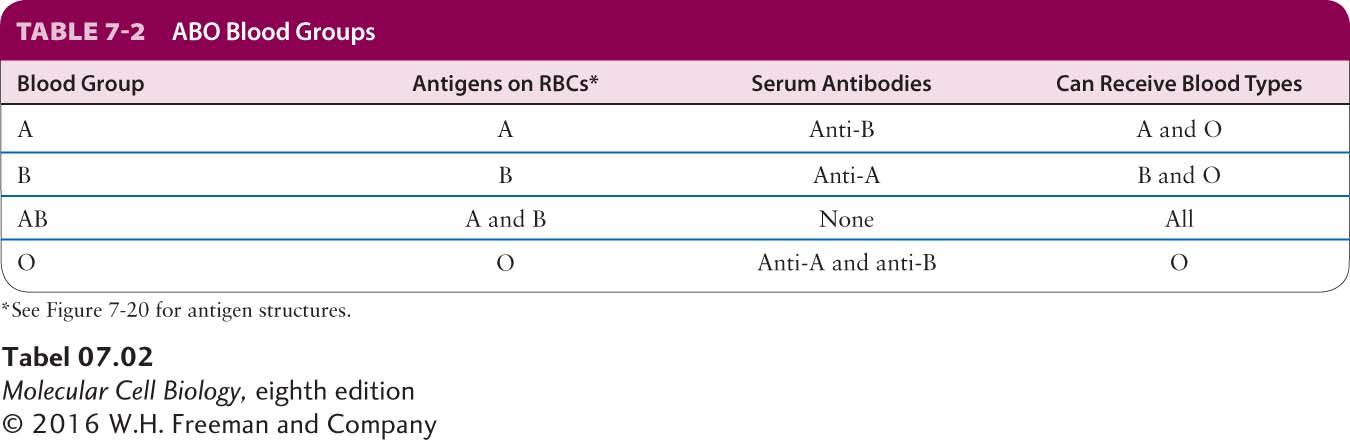

People whose erythrocytes lack the A antigen, the B antigen, or both on their surface normally have antibodies against the missing antigen(s) in their serum. Thus if a type A or O person receives a transfusion of type B blood, antibodies against the B antigen will bind to the introduced red cells and trigger their destruction. To prevent such harmful reactions, blood group typing and appropriate matching of blood donors and recipients are required in all transfusions (Table 7-2).