Chapter 11 Introduction

THE BUSINESS OF MASS MEDIA

11

Advertising and Commercial Culture

Kevin Mazur/BET/Getty Images for BET

There’s a saying in advertising: “Dollars always follow eyeballs.”1 That is, the advertising money flows to whichever medium is attracting people’s attention. Over the past century, those eyeballs have shifted from newspapers and magazines to television to the Internet—

Well, our right eyeball, for now. One of Google’s most talked-

“In today’s multi-

With Glass, Google has invented a new screen for “today’s multi-

Then again, Google Glass might not catch on. Beyond the hefty price tag, potential users may find it too intrusive to have ads delivered directly to their eyes and have their eyeballs tracked for data. Or perhaps people will look dorky in them. Google’s key Glass partner, Leonardo Del Vecchio of Luxottica, the world’s largest eyewear maker, said in September 2014, “I have not used Google Glass. It would embarrass me going around with that on my face. It would be OK in the disco, but I no longer go to the disco.”5

If Google Glass does fail—

TODAY, ADVERTISEMENTS ARE EVERYWHERE AND IN EVERY MEDIA FORM. Ads take up more than half the space in most daily newspapers and consumer magazines. They are inserted into trade books and textbooks. They clutter Web sites on the Internet. They fill our mailboxes and wallpaper the buses we ride. Dotting the nation’s highways, billboards promote fast-

At local theaters and on DVDs, ads now precede the latest Hollywood movie trailers. Corporate sponsors spend millions for product placement: the purchase of spaces for particular goods to appear in a TV show, movie, or music video. Ads are part of a deejay’s morning patter, and ads routinely interrupt our favorite TV and cable programs. By 2012, more than sixteen minutes of each hour of prime-

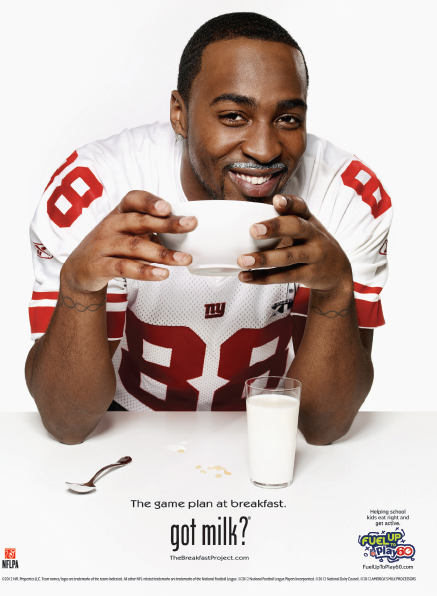

THE “GOT MILK?” advertising campaign was originally designed by Goodby, Silverstein & Partners for the California Milk Processor Board in 1993. Since 1998, the National Milk Processor Board has licensed the “got milk?” slogan for its celebrity milk mustache ads, like this one. Milk Processor Education Program

Advertising comes in many forms, from classified ads to business-

In this chapter, we will:

- Examine the historical development of advertising—

an industry that helped transform numerous nations into consumer societies - Look at the first U.S. ad agencies; early advertisements; and the emergence of packaging, trademarks, and brand-

name recognition - Consider the growth of advertising in the last century, such as the increasing influence of ad agencies and the shift to a more visually oriented culture

- Outline the key persuasive techniques used in consumer advertising

- Investigate ads as a form of commercial speech, and discuss the measures aimed at regulating advertising

- Look at political advertising and its impact on democracy

It’s increasingly rare to find spaces in our society that don’t contain advertising. As you read this chapter, think about your own exposure to advertising. What are some things you like or admire about advertising? For example, are there particular ad campaigns that give you enormous pleasure? How and when do ads annoy you? Can you think of any ways you intentionally avoid advertising? For more questions to help you understand the role of advertising in our lives, see “Questioning the Media” in the Chapter Review.