Social Issues in Media Economics

As the Disney-

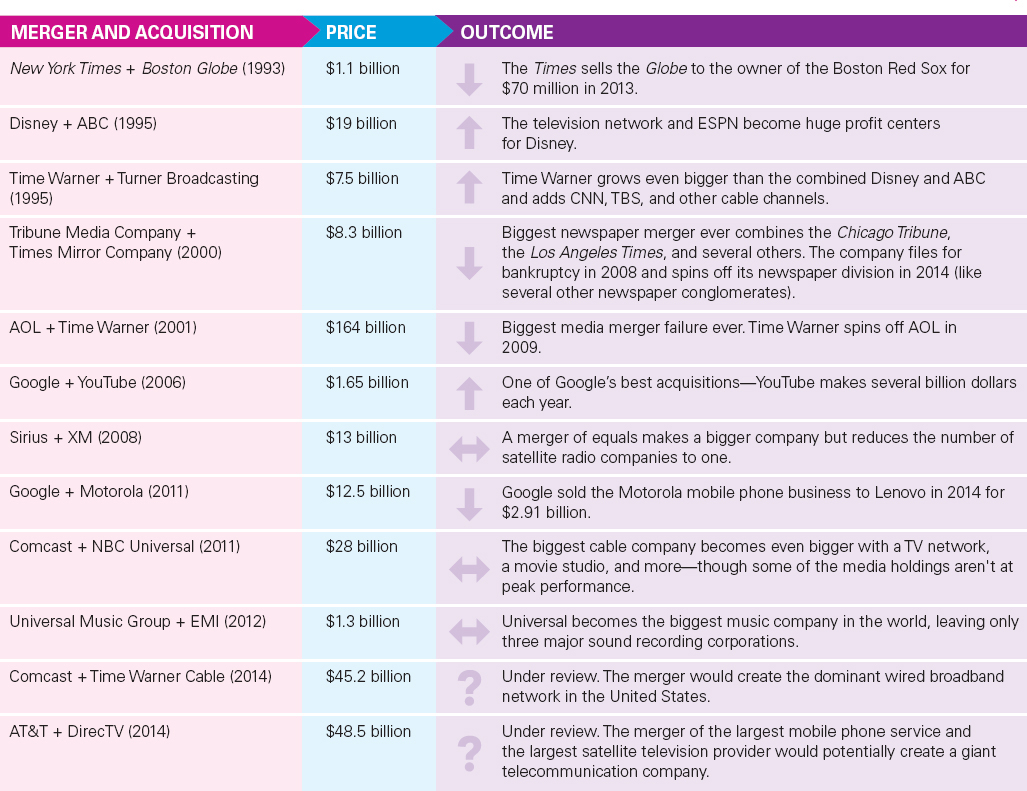

FIGURE 13.4:MAJOR MEDIA MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

| ELSEWHERE IN MEDIA & CULTURE | |

|

|

|

| 24.9M number of tweets by viewers of Super Bowl XLVIII p. 55 | 63.6% amount of Captain America sequel grosses that came from outside the United States p. 257 |

|

$316,912 THE COST OF A THIRTY- |

|

|

|

|

One longtime critic of media mergers, Ben Bagdikian, author of The Media Monopoly, has argued that although there are abundant products in the market—

The Limits of Antitrust Laws

Although meant to ensure multiple voices and owners, American antitrust laws have been easily subverted since the 1980s, as companies expanded by diversifying holdings and merging product lines with other big media firms. Large media firms have also become among the most active and powerful lobbyists in Washington, D.C., and other political capitals. The resulting consolidation of media owners has limited the number of independent voices in the market and reduced the number of owners who might be able to innovate and challenge established economic powers, leading to renewed interest in enforcing antitrust laws.

Diversification

Most media companies diversify among media products (such as television stations and film studios), never fully dominating a particular media industry. Time Warner, for example, spreads its holdings among its television programming, film, publishing, cable, and Internet divisions. However, the media giant actually competes with only a few other big companies, like Disney, Viacom, and 21st Century Fox (the cable, broadcast, and satellite company created in the 2013 split of the News Corp.).

Such diversification promotes oligopolies in which a few behemoth companies control most media production and distribution. This kind of economic arrangement makes it difficult for products offered outside an oligopoly to compete in the marketplace. For instance, in broadcast TV, the few networks that control prime time—

Applying Antitrust Laws Today

Occasionally, independent voices raise issues that aid the Justice Department and the FTC in their antitrust cases. For example, when EchoStar (now the Dish Network) proposed to purchase DirecTV in 2001, a number of rural, consumer, and Latino organizations spoke out against the merger for several reasons. Latino organizations opposed the merger because in many U.S. markets, direct broadcast satellite (DBS) service offers the only available Spanish-

In 2011, AT&T moved to acquire T-

But antitrust laws have no teeth globally. Although international copyright laws offer some protection to musicians and writers, no international antitrust rules exist to prohibit transnational companies from buying up as many media companies as they can afford. Still, as legal scholar Harry First points out, antitrust concerns are “alive and well and living in Europe.”24 For example, when Sony and Bertelsmann’s BMG unit merged their music businesses, only the European Union (EU) raised questions about the merger on behalf of independent labels and musicians worried about the oligopoly structure of the music business. The EU frequently reviewed the merger, starting in 2004, but decided in late 2008 to withdraw its opposition.

CASE STUDY

From Fifty to a Few: The Most Dominant Media Corporations

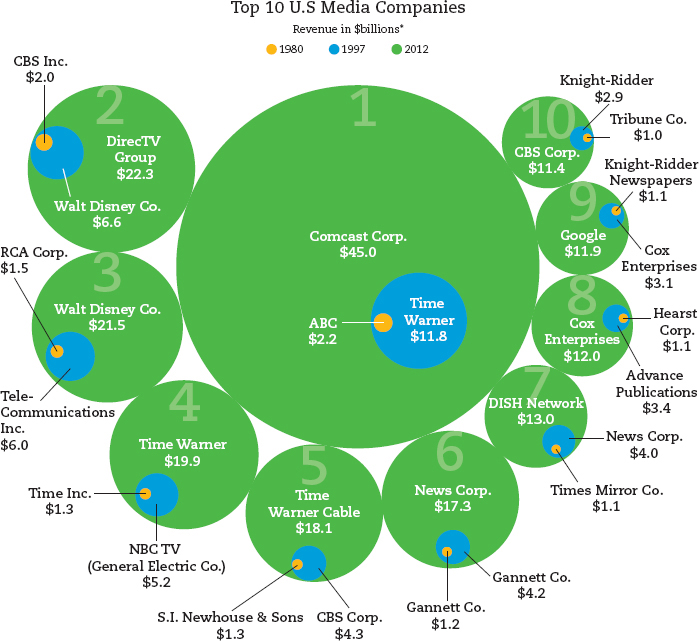

In this graphic that lists the Top 10 media companies for 1980, 1997, and 2012, what patterns do you notice? How do these patterns reflect larger trends in the media? For example, seven of the major companies in 1980 were mostly print businesses, but what about in 2012? Should we trust how NBC News covers Comcast or how ABC News covers Disney? Should we be wary if Time magazine hypes a Warner Brothers film? More important, what actions can we take to ensure that the mass media function not just as successful businesses for stockholders but also as a necessary part of our democracy? Most of the large media companies have been profiled here and in Chapters 2 to 10 (illustrating their principal holdings). Although the subsidiaries of these companies often change, the graphic demonstrates the wide reach of today’s large conglomerations. To get a better understanding of how the largest media corporations relate to one another and the larger world, see the folded insert at the beginning of the book.

Data from: Ad Age’s 100 Leading Media Companies, December 7, 1981; “100 Companies by Media Revenue,” Advertising Age, August 18, 1997; “Media 100,” Advertising Age, December 31, 2012.

*The revenue in $billions is based on total net U.S. media revenue and does not include nonmedia and international revenue.

The Fallout from a Free Market

Since the wave of media mergers began with gusto in the 1980s, a number of consumer critics have pointed to the lack of public debate surrounding the tightening oligopoly structure of international media. Economists and media critics have traced the causes and history of this void to two major issues: a reluctance to criticize capitalism and the debate over how much control consumers have in the marketplace.

Equating Free Markets with Democracy

In the 1920s and 1930s, commercial radio executives, many of whom befriended FCC members, succeeded in portraying themselves as operating in the public interest while labeling their noncommercial radio counterparts in education, labor, or religion as mere voices of propaganda. In these early debates, corporate interests succeeded in aligning the political ideas of democracy, misleadingly, with the economic structures of capitalism.

Throughout the Cold War period in the 1950s and 1960s, it became increasingly difficult to criticize capitalism, which had become a synonym for democracy in many circles. In this context, any criticism of capitalism became an attack on the free marketplace. This, in turn, appeared to be a criticism of free speech because the business community often sees its right to operate in a free marketplace as an extension of its right to buy commercial speech in the form of advertising. As longtime CBS chief William Paley told a group of educators in 1937, “He who attacks the fundamentals of the American system” of commercial broadcasting “attacks democracy itself.”25

Broadcast historian Robert McChesney, discussing the rise of commercial radio during the 1930s, has noted that leaders like Paley “equated capitalism with the free and equal marketplace, the free and equal marketplace with democracy, and democracy with ‘Americanism.’”26 The collapse of the former Soviet Union’s communist economy in the 1990s is often portrayed as a triumph for democracy. As we now realize, however, it was primarily a victory for capitalism and free-

Consumer Choice versus Consumer Control

As many economists point out, capitalism is not structured democratically but arranged vertically, with powerful corporate leaders at the top and hourly wage workers at the bottom. But democracy, in principle, is built on a more horizontal model, in which each individual has an equal opportunity to have his or her voice heard and vote counted. In discussing free markets, economists distinguish between similar types of consumer power: consumer control over marketplace goods and freedom of consumer choice.27 Most Americans and the citizens of other economically developed nations clearly have consumer choice: options among a range of media products. Yet consumers and even media employees have limited consumer control: power in deciding what kinds of media get created and circulated.

One recurring place for democratic production is the work of independent and alternative producers, artists, writers, and publishers. Despite the movement toward economic consolidation, the fringes of media industries still offer a diversity of opinions, ideas, and alternative products. In fact, when independent companies become even marginally popular, they are often pursued by large companies that seek to make them subsidiaries. For example, alternative music often taps into social concerns that are not normally discussed in the recording industry’s corporate boardrooms. Moreover, business leaders “at the top” depend on independent ideas “from below” to generate new product lines. A number of transnational corporations encourage the development of local artists—

Cultural Imperialism

CULTURAL IMPERIALISM

Ever since Hollywood gained an edge in film production and distribution during World War I, U.S. movies have dominated the box office in Europe, in some years accounting for more than 80 percent of the revenues taken in by European theaters. Hollywood’s reach has since extended throughout the world, including previously difficult markets such as China. © Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures/Everett Collection

The influence of American popular culture has created considerable debate in international circles. On the one hand, the notion of freedom that is associated with innovation and rebellion in American culture has been embraced internationally. The global spread of media and increased access to media have made it harder for political leaders to secretly repress dissident groups because police and state activity (such as the torture of illegally detained citizens) can now be documented digitally and easily dispatched by satellite, the Internet, and cell phones around the world.

On the other hand, American media are shaping the cultures and identities of other nations. American styles in fashion and food, as well as media fare, dominate the global market—

Although many indigenous forms of media culture—

Defenders of American popular culture argue that because some aspects of our culture challenge authority, national boundaries, and outmoded traditions, they create an arena in which citizens can raise questions. Supporters also argue that a universal popular culture creates a global village and fosters communication across national boundaries.

Critics, however, such as the authors of the book Global Dreams, believe that although American popular culture often contains protests against social wrongs, such protests “can be turned into consumer products and lose their bite. Protest itself becomes something to sell.”28 The harshest critics have also argued that American cultural imperialism both hampers the development of native cultures and negatively influences teenagers, who abandon their own rituals to adopt American tastes. The exportation of U.S. entertainment media is sometimes viewed as “cultural dumping” because it discourages the development of original local products and value systems.

Perhaps the greatest concern regarding a global village is the cultural disconnection for people whose standards of living are not routinely portrayed in contemporary media. About two-

As early as the 1950s, media managers feared political fallout—