The Business and Ownership of Newspapers

In the news industry today, there are several kinds of papers. National newspapers (such as the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and USA Today) serve a broad readership across the country. Other papers primarily serve specific geographic regions. Roughly 70 metropolitan dailies have a weekday paid circulation of approximately 100,000 (much more if we count digital hits on their Web sites). About 35 of these papers have a circulation of more than 200,000 during the workweek. In addition, about 100 daily newspapers are classified as medium dailies, with circulations between 50,000 and 100,000. By far the largest number of U.S. dailies—

Consensus versus Conflict: Newspapers Play Different Roles

USA TODAY recently took the crown for largest circulation of any newspaper in the United States because inserts that the owner, Gannett, includes in its other high-

Smaller nondaily papers tend to promote social and economic harmony in their communities. Besides providing community calendars and meeting notices, nondaily papers focus on consensus-

In contrast, national and metro dailies practice conflict-

In telling stories about complex and controversial topics, conflict-

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Covering Business and Economic News

The financial crisis and subsequent recession spotlighted newspapers’ coverage of issues such as corporate corruption. For example, since 2008, articles have detailed the collapse of major investment firms like Lehman Brothers, the bailouts of GM and Chrysler, the fraud charges against Goldman Sachs, and of course the scandals surrounding the subprime mortgage–

1 DESCRIPTION. Check a week’s worth of business news in your local paper. Examine both the business pages and the front and local sections for these stories. Devise a chart and create categories for sorting stories (e.g., promotion news, scandal stories, earnings reports, home foreclosures, auto news, unemployment, and media-

2 ANALYSIS. Look for patterns in the coverage. How many stories are positive? How many are negative? Do the stories show any kind of gender favoritism (such as men being covered or featured more than women) or class bias (such as management being favored over workers)? Compared to the coverage in the local paper, are there differences in the frequency and kinds of coverage offered in the national newspaper? Does your paper routinely cover the business of the parent company that owns the local paper? Does it cover national business stories? How many stories are there on the business of newspapers and media in general?

3 INTERPRETATION. What do some of the patterns mean? Did you find examples in which the coverage of business seems comprehensive and fair? If business news gets more positive coverage than political news, what might this mean? If managers get more coverage than employees, what does this mean, given that there are many more regular employees than managers at most businesses? What might it mean if men are more prominently featured than women in business stories? What does it mean if certain businesses are not being covered adequately by local and national news operations? How do business stories cover the economy now in comparison to late 2008 or 2009?

4 EVALUATION. Determine which papers and stories you would judge as stronger models for how business should be covered, and which ones you would judge as weaker models. Are some elements that should be included missing from coverage? If so, make suggestions.

5 ENGAGEMENT. Either write or e-

Newspapers Target Specific Readers

Historically, small-

| ELSEWHERE IN MEDIA & CULTURE | |

| $8.3B THE PRICE OF THE BIGGEST NEWSPAPER MERGER EVER p. 463 | |

MARVEL COMICS ARE A BIG PART OF DISNEY’S CORPORATE STRATEGY p. 460 |

|

| 1887 the year that Nellie Bly caused a sensation in the New York World p. 477 | $31.2B the revenue that print advertising is expected to generate in 2017 p. 385 |

| WHERE CAN YOU FIND JOURNALISTS’ TWEETS COLLECTED IN ONE PLACE? p. 499 | |

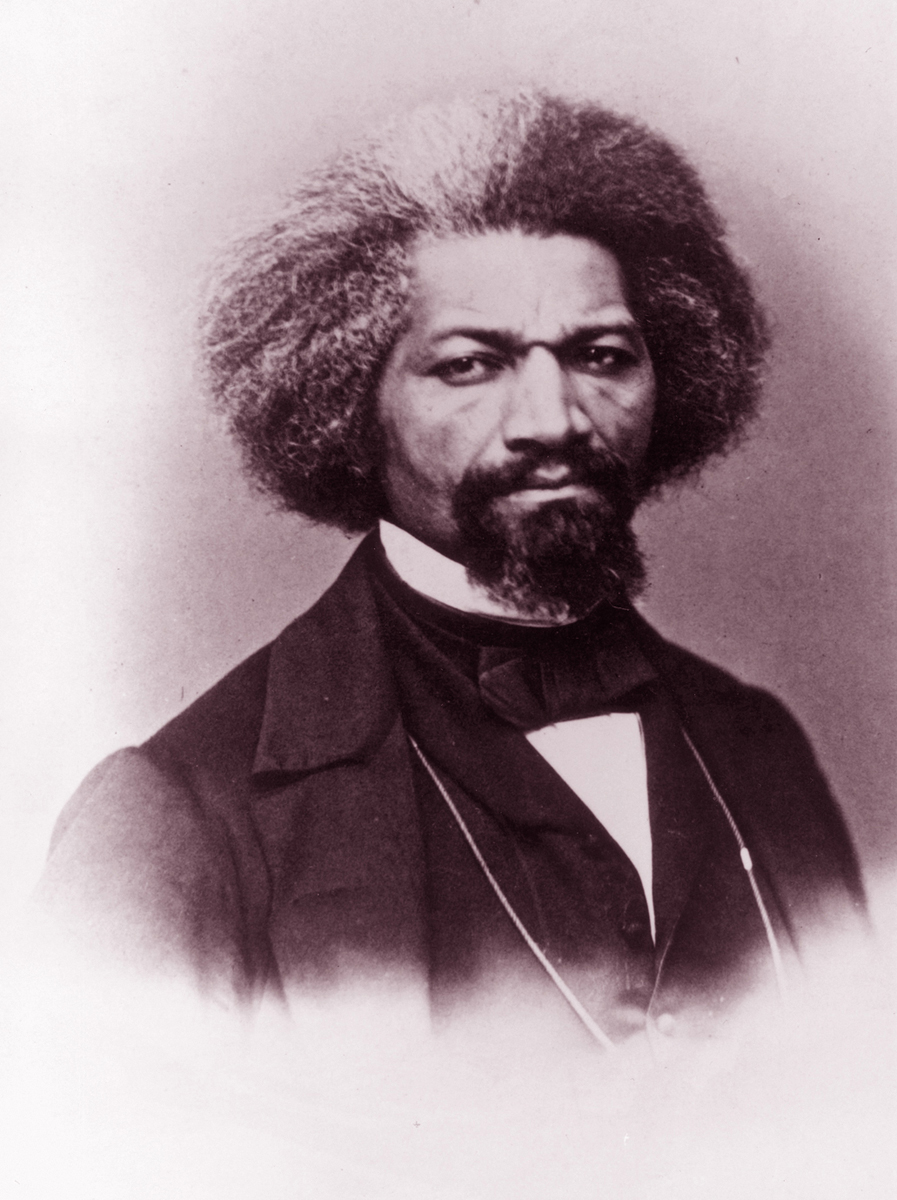

FREDERICK DOUGLASS helped found the North Star in 1847. It was printed in the basement of the Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a gathering spot for abolitionists and “underground” activities in Rochester, New York. At the time, the white-

Throughout the 1990s and into the twenty-

Most of these weekly and monthly newspapers serve some of the same functions for their constituencies—

African American Newspapers

Between 1827 and the end of the Civil War in 1865, forty newspapers directed at black readers and opposed to slavery struggled for survival. These papers faced not only higher rates of illiteracy among potential readers but also hostility from white society and the majority press of the day. The first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, operated from 1827 to 1829 and opposed the racism of many New York newspapers. In addition, it offered a public voice for antislavery societies. Other notable papers included the Alienated American (1852–

Since 1827, 5,500 newspapers have been edited or started by African Americans.25 These papers, with an average life span of nine years, have taken stands against race baiting, lynching, and the Ku Klux Klan. They also promoted racial pride long before the Civil Rights movement. The most widely circulated black-

AFRICAN AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS

This 1936 scene reveals the newsroom of Harlem’s Amsterdam News, one of the nation’s leading African American newspapers. Ironically, the Civil Rights movement and affirmative action policies since the 1960s served to drain talented reporters from the black press by encouraging them to work for larger, mainstream newspapers. © Lucien Aigner/Corbis

The circulation rates of most black papers dropped sharply after the 1960s. The combined circulation of the local and national editions of the Pittsburgh Courier, for instance, dropped from 202,080 in 1944 to 20,000 in 1966, when it was reorganized as the New Pittsburgh Courier. Several factors contributed to these declines. First, television and black radio stations tapped into the limited pool of money that businesses allocated for advertising. Second, some advertisers, to avoid controversy, withdrew their support when the black press started giving favorable coverage to the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s. Third, the loss of industrial urban jobs in the 1970s and 1980s not only diminished readership but also hurt small neighborhood businesses, which could no longer afford to advertise in both the mainstream and the black press. Finally, after the enactment of Civil Rights and affirmative action laws, mainstream papers raided black papers, seeking to integrate their newsrooms with African American journalists. Black papers could seldom match the offers from large white-

While a more integrated mainstream press initially hurt black papers—

According to the ASNE’s 2013 census, of the 38,000 reporters and editors at daily newspapers, “about 4,700 or 12.37 percent [were] racial minorities; the percentage of minority employees has consistently hovered between 12 and 13 percent for more than a decade.” Among the ASNE’s main goals, however, “is to have the percentage of minorities working in newsrooms nationwide reflect the percentage of the nation’s population by 2025.” In 2013, minorities made up about 37 percent of the U.S. population, and the U.S. Census Bureau has reported that the number will increase to more than 42 percent by 2025.28

Spanish-

Bilingual and Spanish-

Asian American Newspapers

THE WORLD JOURNAL is a national daily paper that targets Chinese immigrants by focusing on news from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other Southeast Asian communities. Courtesy of the World Journal

In the 1980s, hundreds of small papers emerged to serve immigrants from Pakistan, Laos, Cambodia, and China. While people of Asian descent made up only about 5.3 percent of the U.S. population in 2013, this percentage is expected to rise to 9 percent by 2050.32 Today, fifty small U.S. papers are printed in Vietnamese. Ethnic papers like these help readers both adjust to foreign surroundings and retain ties to their traditional heritage. In addition, these papers often cover major stories downplayed in the mainstream press. For example, in the aftermath of 9/11, airport security teams detained thousands of Middle Eastern–

A growth area in newspapers is Chinese publications. Even amid a poor economy, a new Chinese newspaper, News for Chinese, started in 2008. The Chinese-

Native American Newspapers

An activist Native American press has provided oppositional voices to mainstream American media since 1828, when the Cherokee Phoenix appeared in Georgia. Another prominent early paper was the Cherokee Rose Bud, founded in 1848 by tribal women in the Oklahoma territory. The Native American Press Association has documented more than 350 Native American papers, most of them printed in English but a few in tribal languages. Currently, two national papers are the Native American Times, which offers perspectives on “sovereign rights, civil rights, and government-

To counter the neglect of Native American culture’s viewpoints by the mainstream press, Native American newspapers have helped educate various tribes about their heritage and have helped build community solidarity. These papers have also reported on both the problems and the progress among tribes that have opened casinos and gambling resorts. Overall, these smaller papers provide a forum for debates on tribal conflicts and concerns, and they often signal the mainstream press on issues—

The Underground Press

The mid to late 1960s saw an explosion of alternative newspapers. Labeled the underground press at the time, these papers questioned mainstream political policies and conventional values, often voicing radical opinions. Generally running on shoestring budgets, they were also erratic in meeting publication schedules. Springing up on college campuses and in major cities, underground papers were inspired by the writings of socialists and intellectuals from the 1930s and 1940s and by a new wave of thinkers and artists. Particularly inspirational were poets and writers (such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, LeRoi Jones, and Eldridge Cleaver) and “protest” musicians (including Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez). In criticizing social institutions, alternative papers questioned the official reports distributed by public relations agents, government spokespeople, and the conventional press (see “Case Study: Alternative Journalism: Dorothy Day and I. F. Stone” on page 292).

During the 1960s, underground papers played a unique role in documenting social tension by including the voices of students, women, African Americans, Native Americans, gay men and lesbians, and others whose opinions were often excluded from the mainstream press. The first and largest underground paper, the Village Voice, was founded in Greenwich Village in 1955. It is still distributed free, surviving through advertising, though its staff has been cut heavily in recent years. But circulation figures for free alternative weeklies are often difficult to pin down. While the Pew Research Center reported the Village Voice circulation at 144,000 in 2013, the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies (AAN) listed the paper’s circulation at 80,000 in both 2013 and 2014.36

Among campus underground papers, the Berkeley Barb was the most influential, developing amid the free-

CASE STUDY

Alternative Journalism: Dorothy Day and I. F. Stone

Over the years, a number of unconventional reporters have struggled against the status quo to find a place for unheard voices and alternative ways to practice their craft. For example, Ida Wells fearlessly investigated violence against blacks for the Memphis Free Speech in the late nineteenth century. Newspaper lore offers a rich history of alternative journalists and their publications, such as Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker and I. F. Stone’s Weekly.

© Bettmann/Corbis

In 1933, Dorothy Day (1897–

AP Images

For more than eighty years, the Worker has consistently advocated personal activism to further social justice, opposing anti-

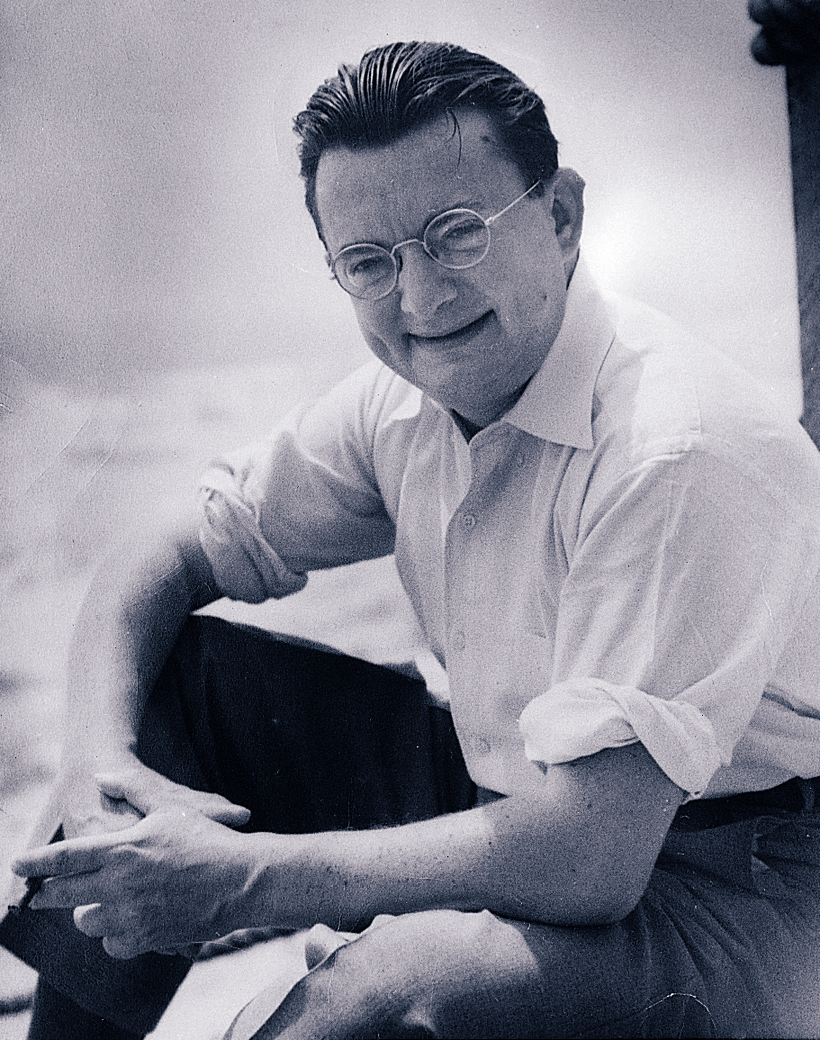

I. F. Stone (1907–

When the Daily Compass failed in 1952, the radical Stone was unable to find a newspaper job and decided to create his own newsletter, I. F. Stone’s Weekly, which he published for nineteen years. Practicing interpretive and investigative reporting, Stone became as adept as any major journalist at tracking down government records to discover contradictions, inaccuracies, and lies. Over the years, Stone questioned decisions by the Supreme Court, investigated the substandard living conditions of many African Americans, and criticized political corruption. He guided the Weekly to a circulation that reached seventy thousand during the 1960s, when he probed American investments of money and military might in Vietnam.

I. F. Stone and Dorothy Day embodied a spirit of independent reporting that has been threatened by first the rise of chain ownership, then the decline in readership. Stone, who believed that alternative ideas were crucial to maintaining a healthy democracy, once wrote that “there must be free play for so-

Newspaper Operations

Today, a weekly paper might employ only two or three people, while a major metro daily might have a staff of more than one thousand, including workers in the newsroom and online operations, and in departments for circulation (distributing the newspaper), advertising (selling ad space), and mechanical operations (assembling and printing the paper). In either situation, however, most newspapers distinguish business operations from editorial or news functions. Journalists’ and readers’ praise or criticism usually rests on the quality of a paper’s news and editorial components, but business and advertising concerns today dictate whether papers will survive.

Most major daily papers would like to devote one-

News and Editorial Responsibilities

The chain of command at most larger papers starts with the publisher and owner at the top and then moves, on the news and editorial side, to the editor in chief and managing editor, who are in charge of the daily news-

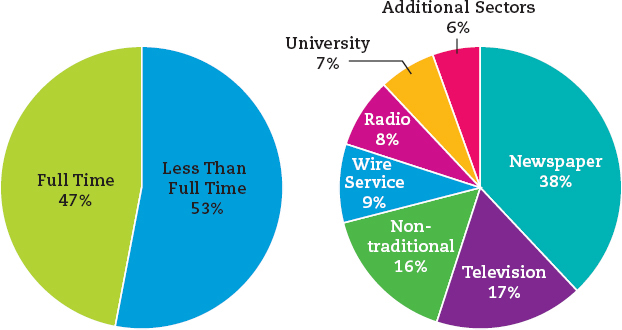

FIGURE 8.1 WHO REPORTS FROM U.S. STATEHOUSES? (PERCENTAGE OF ALL STATEHOUSE REPORTERS) Note: The “less than full-

Reporters work for editors. General assignment reporters handle all sorts of stories that might emerge—

POLITICAL CARTOONS are often syndicated features in newspapers and reflect the issues of the day. by RJ Matson/Politicalcartoons.com

Recent consolidation and cutbacks have led to layoffs and the closing of bureaus outside a paper’s city limits. For example, in 1985, more than 600 newspapers had reporters stationed in Washington, D.C.; in 2013, that number was under 250. The Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the Baltimore Sun—all owned now by Tribune Publishing—

The downside of these money-

Wire Services and Feature Syndication

Major daily papers might have one hundred or so local reporters and writers, but they still cannot cover the world or produce enough material to fill up the newshole each day. Newspapers rely on wire services and syndicated feature services to supplement local coverage. A few major dailies, such as the New York Times, run their own wire services, selling their stories to other papers to reprint. Other agencies, such as the Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI), have hundreds of staffers stationed throughout major U.S. cities and world capitals. They submit stories and photos each day for distribution to newspapers across the country. Some U.S. papers also subscribe to foreign wire services, such as Agence France-

Daily papers generally pay monthly fees for access to all wire stories. Although they use only a fraction of what is available over the wires, editors monitor wire services each day for important stories and ideas for local angles. Wire services have greatly expanded the reach and scope of news, as local editors depend on wire firms when they select statewide, national, or international reports for reprinting.

In addition, traditional feature syndicates, such as United Features (now known as Universal Uclick) and Tribune Media Services (now known as Gracenote), operated historically as commercial outlets that contracted with newspapers to provide work from the nation’s best political writers, editorial cartoonists, comic-

Newspaper Ownership: Chains Lose Their Grip

Edward Wyllis Scripps founded the first newspaper chain—a company that owns several papers throughout the country—

By the 1980s, more than 130 chains owned an average of nine papers each, with the 12 largest chains accounting for 40 percent of total circulation in the United States. By 2001, the top ten chains controlled more than one-

Around 2005, consolidation in newspaper ownership leveled off because the decline in newspaper circulation and ad sales panicked investors, leading to drops in the stock value of newspapers. Many newspaper chains responded by significantly reducing their newsroom staffs and selling off individual papers.

For an example of this cost cutting, consider actions at the Los Angeles Times (then owned by the Chicago-

About the same time, large chains started to break up, selling individual newspapers to private equity firms and big banks (like Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase) that deal in distressed and overleveraged companies with too much debt. For example, in 2006, Knight Ridder—

On a more promising note, in 2012, billionaire philanthropist Warren Buffett, CEO of the investment firm Berkshire Hathaway, spent $344 million and bought more than sixty newspapers (the company planned to retain about thirty). A newspaper junkie and former paperboy, Buffett has owned the Buffalo News in New York since 1977 and has run it profitably. In 2011, he also bought his hometown paper, the Omaha World-

While Warren Buffett concentrated on purchasing smaller regional papers, ownership of one of the nation’s three national newspapers also changed hands. Back in 2007, the Wall Street Journal, held by the Bancroft family for more than one hundred years, accepted a bid of nearly $5.8 billion from News Corp. head Rupert Murdoch (News Corp. also owns the New York Post and many papers in the United Kingdom and Australia). At the time, critics raised serious concerns about takeovers of newspapers by large entertainment conglomerates (Murdoch’s company at the time also owned TV stations, a network, cable channels, and a movie studio). As small subsidiaries in large media empires, newspapers are increasingly treated as just another product line that is expected to perform in the same way that a movie or TV program does. But in 2012, News Corp. decided to split its news and entertainment divisions, leading some critics to hope that Murdoch’s news operations would no longer be subject to the same high-

As chains lose their grip, there are concerns about who will own papers in the future and the effect the papers’ owners will have on content and press freedoms. Recent purchases by private equity groups are alarming, since these companies are usually more interested in turning a profit than supporting journalism. However, ideas exist for how to avoid this fate. For example, more support could be rallied for small independent owners, who could then make decisions based on what’s best for the paper—

Joint Operating Agreements Combat Declining Competition

Although the amount of regulation preventing newspaper monopolies has decreased, the government continues to monitor the declining number of newspapers in various American cities as well as mergers in cities where competition among papers might be endangered. In the mid-

In 1970, Congress passed the Newspaper Preservation Act, which enabled failing papers to continue operating through a joint operating agreement (JOA). Under a JOA, two competing papers keep separate news divisions while merging business and production operations for a period of years. Since the act’s passage, twenty-

For example, Detroit was one of the most competitive newspaper cities in the nation until 1989. The Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press, then owned by Gannett and Knight Ridder, respectively, both ranked among the ten most widely circulated papers in the country and sold their weekday editions for just fifteen cents a copy. Faced with declining revenue and increased costs, the papers’ managers asked for and received a JOA in 1989. But problems continued. Then, in 1995, a prolonged and bitter strike by several unions sharply reduced circulation, as the strikers formed a union-