Exercises

Clarifying the Concepts

Question 13.1

| 13.1 |

What is a correlation coefficient? |

Question 13.2

| 13.2 |

What is a linear relation? |

Question 13.3

| 13.3 |

Describe a perfect correlation, including its possible coefficients. |

Question 13.4

| 13.4 |

What is the difference between a positive correlation and a negative correlation? |

Question 13.5

| 13.5 |

What magnitude of a correlation coefficient is large enough to be considered important, or worth talking about? |

Question 13.6

| 13.6 |

When we have a straight- |

Question 13.7

| 13.7 |

Explain how the correlation coefficient can be used as a descriptive or an inferential statistic. |

Question 13.8

| 13.8 |

How are deviation scores used in assessing the relation between variables? |

Question 13.9

| 13.9 |

Explain how the sum of the product of deviations determines the sign of the correlation. |

Question 13.10

| 13.10 |

What are the null and research hypotheses for correlations? |

Question 13.11

| 13.11 |

What are the three basic steps to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient? |

Question 13.12

| 13.12 |

Describe the third assumption of hypothesis testing with correlation. |

Question 13.13

| 13.13 |

What is the difference between test– |

Question 13.14

| 13.14 |

Why is a correlation coefficient never greater than 1 (or less than −1)? |

Calculating the Statistics

Question 13.15

| 13.15 |

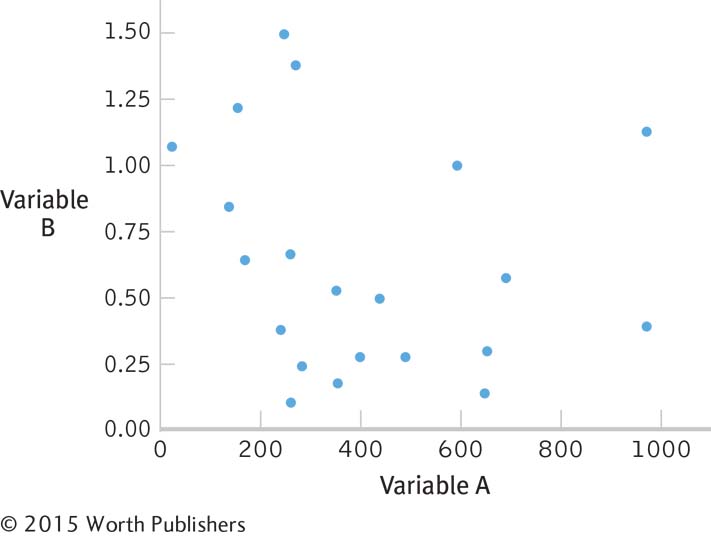

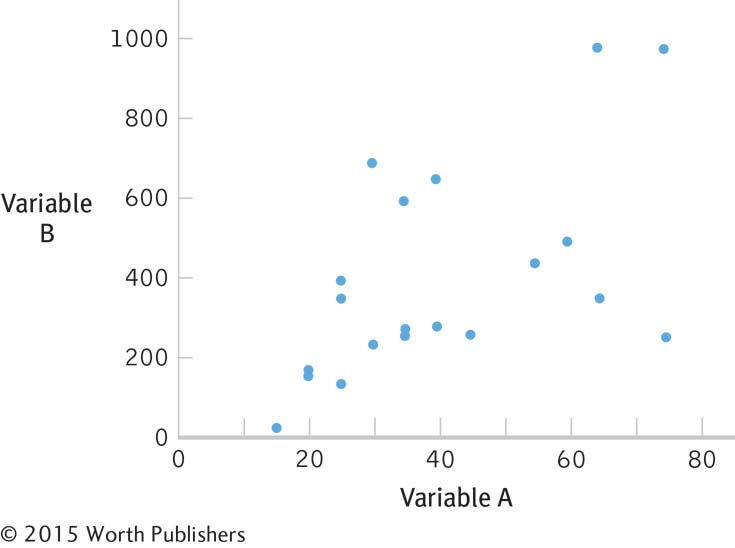

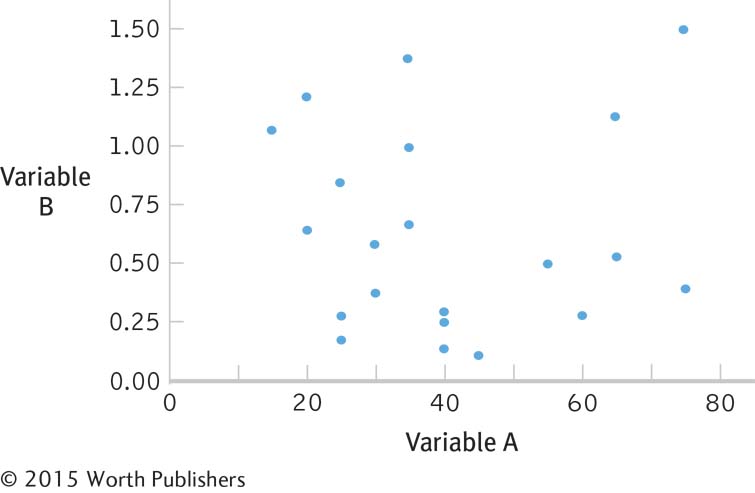

Determine whether the data in each of the graphs provided would result in a negative or positive correlation coefficient.

|

Question 13.16

| 13.16 |

Decide which of the three correlation coefficient values below goes with each of the scatterplots presented in Exercise 13.15.

|

Question 13.17

| 13.17 |

Use Cohen’s guidelines to describe the strength of the following correlation coefficients:

|

Question 13.18

| 13.18 |

For each of the pairs of correlation coefficients provided, determine which one indicates a stronger relation between variables:

|

Question 13.19

| 13.19 |

Using the following data:

|

Question 13.20

| 13.20 |

Using the following data:

|

Question 13.21

| 13.21 |

Using the following data:

|

Question 13.22

| 13.22 |

Calculate the degrees of freedom and the critical values, or cutoffs, assuming a two-

|

Question 13.23

| 13.23 |

Calculate the degrees of freedom and the critical values, or cutoffs, assuming a two-

|

Question 13.24

| 13.24 |

Which of the following is not a possible coefficient alpha: 1.67, 0.12, −0.88? Explain your answer. |

Question 13.25

| 13.25 |

A researcher is deciding among three diagnostic tools. The first has a coefficient alpha of 0.82, the second has one of 0.95, and the third has one of 0.91. Based on this information, which tool would you suggest she use and why? |

Applying the Concepts

Question 13.26

| 13.26 |

Awe and correlation in the news: The New York Times reported on a study that examined the link between positive emotions and health. First citing previous research connecting negative moods with poor health, the reporter said: “Far less is known, however, about the health benefits of specific upbeat moods— If this study were an experiment, how might the researchers have studied the emotion of awe as a medicine?

|

Question 13.27

| 13.27 |

Debunking astrology with correlation: The New York Times reported that an officer of the International Society for Astrological Research, Anne Massey, stated that a certain phase of the planet Mercury, the retrograde phase, leads to breakdowns in areas as wide-

|

Question 13.28

| 13.28 |

Obesity, age at death, and correlation: In a newspaper column, Paul Krugman (2006) mentioned obesity (as measured by body mass index) as a possible correlate of age at death.

|

Question 13.29

| 13.29 |

Exercise, number of friends, and correlation: Does the amount that people exercise correlate with the number of friends they have? The accompanying table contains data collected in some of our statistics classes. The first and third columns show hours exercised per week and the second and fourth columns show the number of close friends reported by each participant.

|

Question 13.30

| 13.30 |

Externalizing behavior, anxiety, and correlation: As part of their study on the relation between rejection and depression in adolescents (Nolan, Flynn, & Garber, 2003), researchers collected data on externalizing behaviors (e.g., acting out in negative ways, such as causing fights) and anxiety. They wondered whether externalizing behaviors were related to feelings of anxiety. Some of the data are presented in the accompanying table.

|

Question 13.31

| 13.31 |

Externalizing behavior, anxiety, and hypothesis testing for correlation: Using the data in the previous exercise, perform all six steps of hypothesis testing to explore the relation between externalizing and anxiety. |

Question 13.32

| 13.32 |

Direction of a correlation: For each of the following pairs of variables, would you expect a positive correlation or a negative correlation between the two variables? Explain your answer.

|

Question 13.33

| 13.33 |

Cats, mental health problems, and the direction of a correlation: You may be aware of the stereotype about the “crazy” person who owns a lot of cats. Have you wondered whether the stereotype is true? As a researcher, you decide to assess 100 people on two variables: (1) the number of cats they own, and (2) their level of mental health problems (a higher score indicates more problems).

|

Question 13.34

| 13.34 |

Cats, mental health problems, and scatterplots: Consider the scenario in the previous exercise again. The two variables under consideration were (1) number of cats owned, and (2) level of mental health problems (with a higher score indicating more problems). Each possible relation between these variables would be represented by a different scatterplot. Using data for approximately 10 participants, draw a scatterplot that depicts a correlation between these variables for each of the following:

|

Question 13.35

| 13.35 |

Trauma, femininity, and correlation: Graduate student Angela Holiday (2007) conducted a study examining perceptions of combat veterans suffering from mental illness. Participants read a description of either a male or female soldier who had recently returned from combat in Iraq and who was suffering from depression. Participants rated the situation (combat in Iraq) with respect to how traumatic they believed it was; they also rated the combat veterans on a range of variables, including scales that assessed how masculine and how feminine they perceived the person to be. Among other analyses, Holiday examined the relation between the perception of the situation as traumatic and the perception of the veteran as being masculine or feminine. When the person was male, the perception of the situation as traumatic was strongly positively correlated with the perception of the man as feminine but was only weakly positively correlated with the perception of the man as masculine. What would you expect when the person was female? The accompanying table presents some of the data for the perception of the situation as traumatic (on a scale of 1– Page 387

|

Question 13.36

| 13.36 |

Trauma, femininity, and hypothesis testing for correlation: Using the data and your work in the previous exercise, perform the remaining five steps of hypothesis testing to explore the relation between trauma and femininity. In step 6, be sure to evaluate the size of the correlation using Cohen’s guidelines. [You completed step 5, the calculation of the correlation coefficient, in 13.35(b).] |

Question 13.37

| 13.37 |

Trauma, masculinity, and correlation: See the description of Holiday’s experiment in Exercise 13.35. We calculated the correlation coefficient for the relation between the perception of a situation as traumatic and the perception of a woman’s femininity. Now let’s look at data to examine the relation between the perception of a situation as traumatic and the perception of a woman’s masculinity (on a scale of 1–

|

Question 13.38

| 13.38 |

Trauma, masculinity, and hypothesis testing for correlation: Using the data and your work in the previous exercise, perform the remaining five steps of hypothesis testing to explore the relation between trauma and masculinity. In step 6, be sure to evaluate the size of the correlation using Cohen’s guidelines. [You completed step 5, the calculation of the correlation coefficient, in 13.37(b).] |

Question 13.39

| 13.39 |

Traffic, running late, and bias: A friend tells you that there is a correlation between how late she’s running and the amount of traffic. Whenever she’s going somewhere and she’s behind schedule, there’s a lot of traffic. And when she has plenty of time, the traffic is sparser. She tells you that this happens no matter what time of day she’s traveling or where she’s going. She concludes that she’s cursed with respect to traffic.

|

Question 13.40

| 13.40 |

IQ- |

Question 13.41

| 13.41 |

Driving a convertible, correlation, and causality: How safe are convertibles? USA Today (Healey, 2006) examined the pros and cons of convertible automobiles. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the newspaper reported, determined that, depending on the model, 52 to 99 drivers of 1 million registered convertibles died in a car crash. The average rate of deaths for all passenger cars was 87. “Counter to conventional wisdom,” the reporter wrote, “convertibles generally aren’t unsafe.” Page 388

|

Question 13.42

| 13.42 |

Standardized tests, correlation, and causality: A New York Times editorial (“Public vs. Private Schools,” 2006) cited a finding by the U.S. Department of Education that standardized test scores were significantly higher among students in private schools than among students in public schools.

|

Question 13.43

| 13.43 |

Arts education, correlation, and causality: The Broadway musical Annie and the Entertainment Industry Foundation teamed up to promote arts education programs for underserved children. In an ad in the New York Times, they said, “Students in arts education programs perform better and stay in school longer.”

|

Question 13.44

| 13.44 |

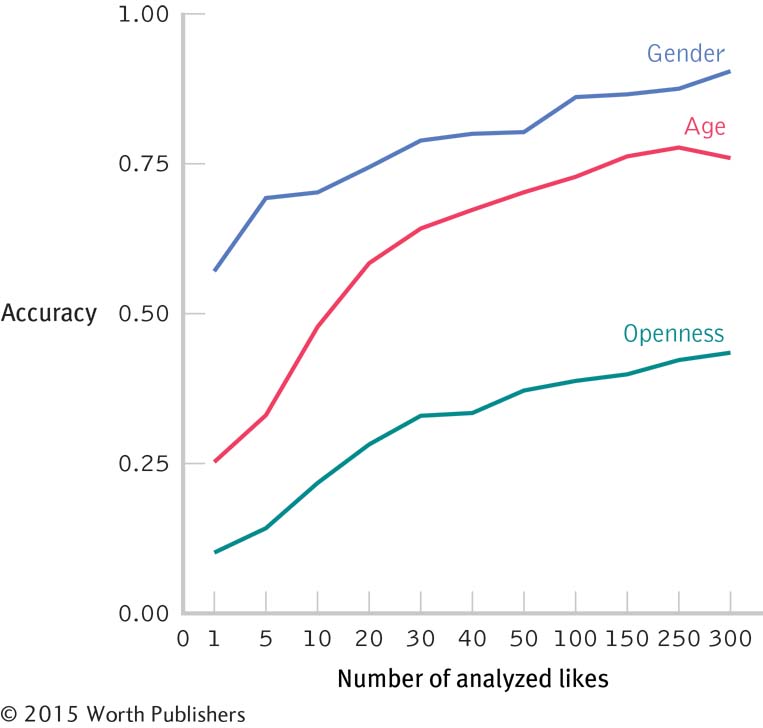

Facebook likes and correlation: Be careful what you “like.” Researchers examined the relations between the number of Facebook “likes” a person has posted and the researchers’ ability to correctly identify various characteristics of the person, including gender, age, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, political beliefs, personality traits, and intelligence (Kosinski, Stillwell, & Graepel, 2013). The graph at top right shows the relations between number of likes and accuracy of identifying gender, age, and the personality characteristic of openness, respectively.

|

Question 13.45

| 13.45 |

Athletes’ grades, scatterplots, and correlation: At the university level, the stereotype of the “dumb jock” might be strong and ever present; however, a fair amount of research shows that athletes maintain decent grades and competitive graduation rates when compared to nonathletes. Let’s play with some data to explore the relation between grade point average (GPA) and participation in athletics. Data are presented here for a hypothetical basketball team, including the GPA on a scale of 0.00 to 4.00 for each athlete and the average number of minutes played per game.

Page 389

|

Question 13.46

| 13.46 |

Romantic love, brain activation, and reliability: Aron and colleagues (2005) found a correlation between intense romantic love [as assessed by the Passionate Love Scale (PLS)] and activation in a specific region of the brain [as assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)]. The PLS (Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986) assessed the intensity of romantic love by asking people in romantic relationships to respond to a series of questions, such as “I want ______ physically, emotionally, and mentally” and “Sometimes I can’t control my thoughts; they are obsessively on ______,” replacing the blanks with the name of their partner.

|

Question 13.47

| 13.47 |

A biased exam question, validity, and correlation: New York State’s fourth-

|

Question 13.48

| 13.48 |

Holiday weight gain, reliability, and validity: The Wall Street Journal reported on a study of holiday weight gain. Researchers assessed weight gain by asking people how much weight they typically gain in the fall and winter (Parker-

|

Putting It All Together

Question 13.49

| 13.49 |

Health care spending, longevity, and correlation: New York Times columnist Paul Krugman (2006) used the idea of correlation in a newspaper column when he asked, “Is being an American bad for your health?” Krugman explained that the United States has higher per capita spending on health care than any country in the world and yet is surpassed by many countries in life expectancy [Krugman cited a study by Banks, Marmot, Oldfield, and Smith (2006), published in the Journal of the American Medical Association]. Page 390

|

Question 13.50

| 13.50 |

Availability of food, amount eaten, and correlation: Did you know that sometimes you eat more just because the food is in front of you? Geier, Rozin, and Doros (2006) studied how portion size affected the amount people consumed. They discovered interesting things such as that people eat more M&M’s when the candies are dispensed using a big spoon as compared with when a small spoon is used. They investigated whether people eat more when more food is available. Hypothetical data are presented below for the amount of candy presented in a bowl for customers to take and the amount of candy taken by the end of each day of the study:

|

Question 13.51

| 13.51 |

High school athletic participation and correlation: Researchers examined longitudinal data to explore the long-

|