1.4 Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is the process of drawing conclusions about whether a particular relation between variables is supported by the evidence.

When John Snow suggested that the pump handle be removed from the Broad Street well, he was testing his idea that an independent variable (contaminated well water) led to a dependent variable (deaths from cholera). Behavioral scientists use research to test ideas through a specific statistics-

Determining which breed of dog you most resemble might seem silly; however, adopting a dog is a very important decision. Can an online quiz such as the Animal Planet “Dog Breed Selector” help (http:/

An operational definition specifies the operations or procedures used to measure or manipulate a variable.

An operational definition specifies the operations or procedures used to measure or manipulate a variable. We could operationalize a good outcome with a new dog in several ways. Did you keep the dog for more than a year? On a rating scale of satisfaction with your pet, did you get a high score? Does a veterinarian give a high rating to your dog’s health?

Do you think a quiz would lead you to make a better choice in dogs? You might hypothesize that the quiz would lead to better choices because it makes you think about important factors in dog ownership, such as outdoor space, leisure time, and your tolerance for dog hair. You already carry many hypotheses like these in your head. You just haven’t bothered to test most of them yet, at least not formally. For example, perhaps you believe that North Americans use banking machines (ATMs) faster than Europeans do, or that smokers simply lack the willpower to stop. Maybe you are convinced that the parking problem on your campus is part of a conspiracy by administrators to make your life more difficult.

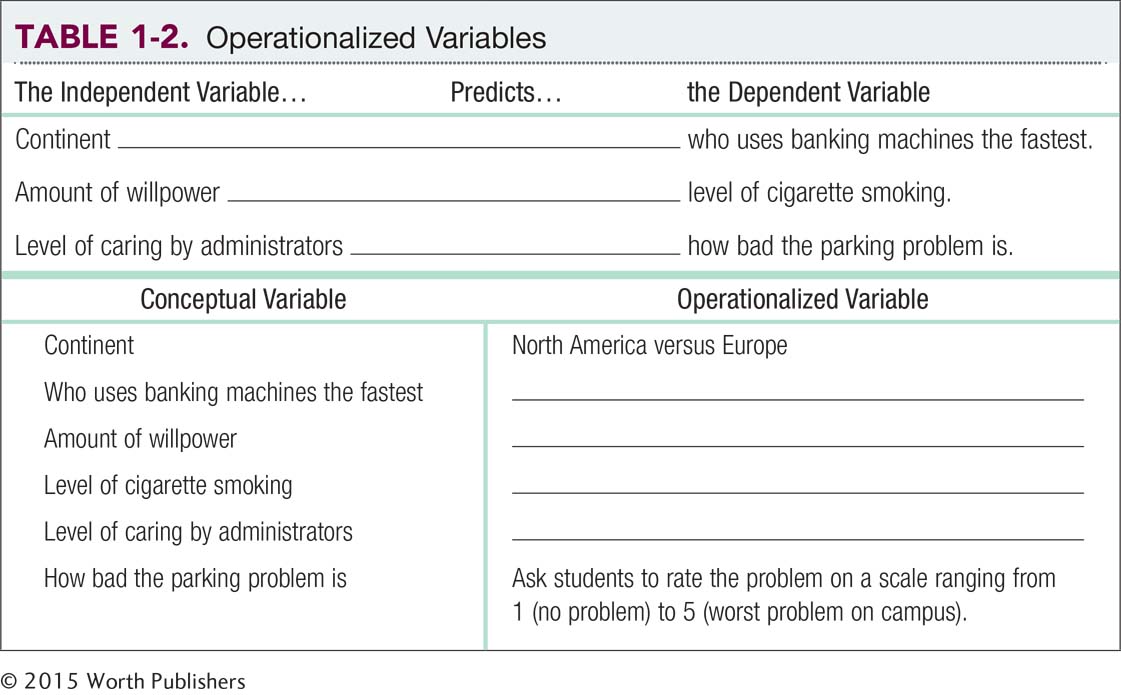

In each of these cases, as shown in the accompanying table, we frame a hypothesis in terms of an independent variable and a dependent variable. The best way to learn about operationalizing a variable is to experience it for yourself. So propose a way to measure each of the variables identified in Table 1-2. We’ve given you a start with “continent”—North America versus Europe (easy to operationalize)—and “how bad the parking problem is” (more difficult to operationalize).

Conducting Experiments to Control for Confounding Variables

A correlation is an association between two or more variables.

Once we have decided how to operationalize the variables, we can conduct a study and collect data. There are several ways to approach research, including experiments and correlational research. A correlation is an association between two or more variables. In Snow’s cholera research, it was the idea of a systematic co-

With random assignment, every participant in a study has an equal chance of being assigned to any of the groups, or experimental conditions, in the study.

An experiment is a study in which participants are randomly assigned to a condition or level of one or more independent variables.

The hallmark of experimental research is random assignment. With random assignment, every participant in the study has an equal chance of being assigned to any of the groups, or experimental conditions, in the study. And an experiment is a study in which participants are randomly assigned to a condition or level of one or more independent variables. Random assignment means that neither the participants nor the researchers get to choose the condition. Experiments are the gold standard of hypothesis testing because they are the best way to control confounding variables. Controlling confounding variables allows researchers to infer a cause–

When researchers conduct experiments, they create approximately equivalent groups by randomly assigning participants to different levels, or conditions, of the independent variable. Random assignment controls the effects of personality traits, life experiences, personal biases, and other potential confounds by distributing them evenly across each condition of the experiment.

EXAMPLE 1.1

It is difficult to control confounding variables, so let’s see how random assignment helps to do that. You might wonder whether the hours you spend playing Angry Birds or Call of Duty are useful. A team of physicians and a psychologist investigated whether video game playing (the independent variable) leads to superior surgical skills (the dependent variable). They reported that surgeons with more video game playing experience were faster and more accurate, on average, when conducting training drills that mimic laparoscopic surgery (a surgical technique that uses a small incision, a small video camera, and a video monitor) than surgeons with no video game playing experience (Rosser et al., 2007).

MASTERING THE CONCEPT

1-

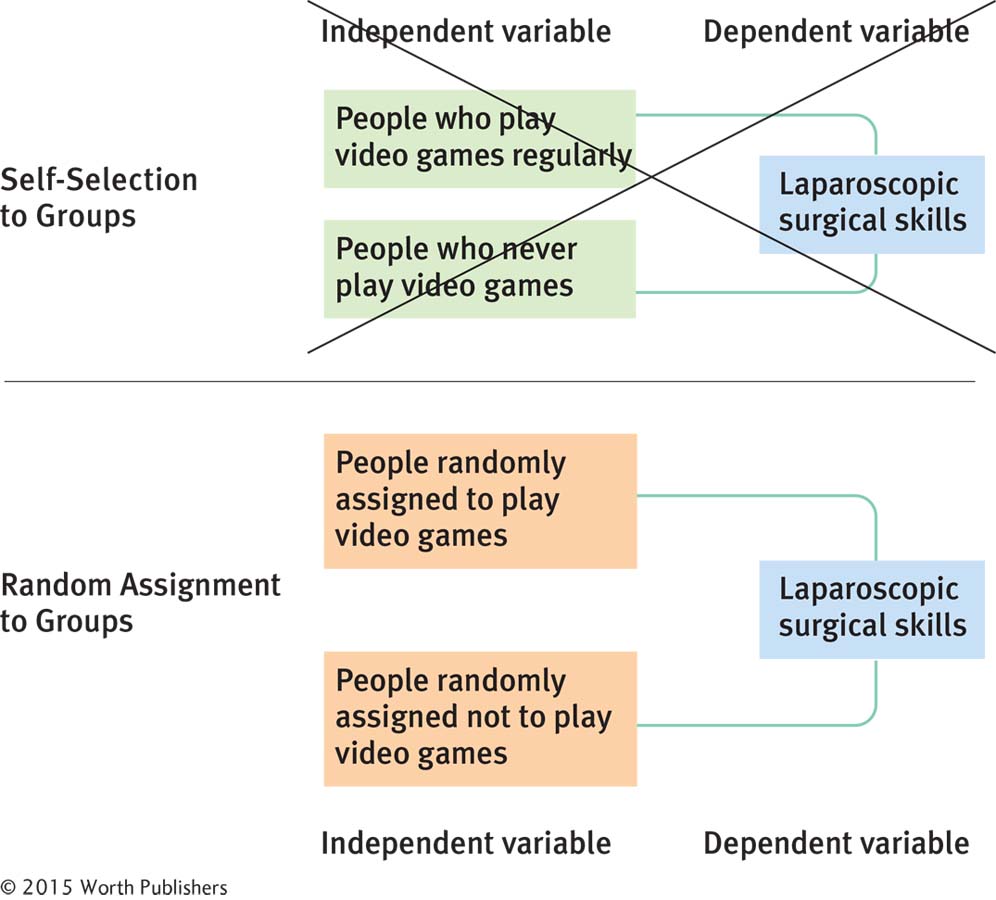

In the video game and surgery study, the researchers did not randomly assign surgeons to play video games or not. Rather, they asked surgeons to report their video game playing histories and then measured their laparoscopic surgical skills. Can you spot the confounding variable? People may choose to play video games because they already have the fine motor skills and eye–

It would be much more useful to set up an experiment that randomly assigns surgeons to one of the two levels of the independent variable: (1) play video games or (2) do not play video games. Random assignment assures us that our two groups are roughly equal, on average, on all the variables that might contribute to excellent surgical skills, such as fine motor skills, eye–

Self-

This figure visually clarifies the difference between self-

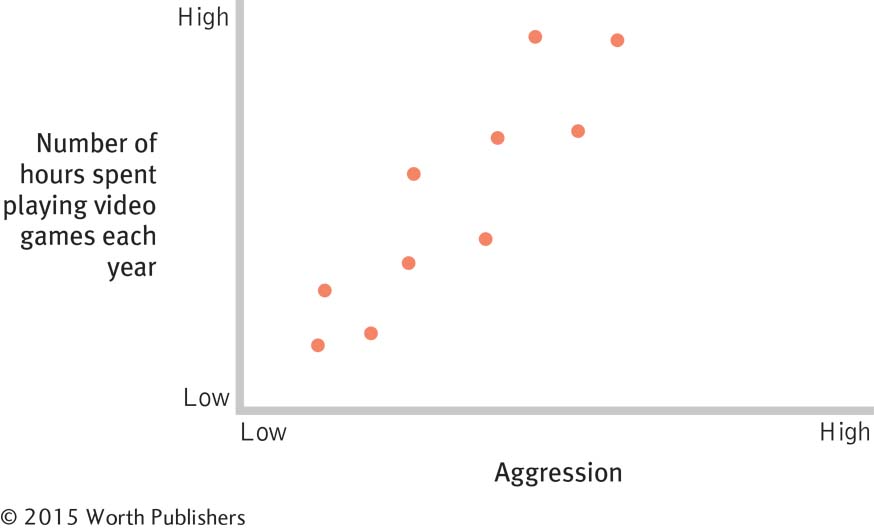

Correlation Between Aggression and Playing Video Games

This graph depicts a relation between aggression and hours spent playing video games for a study of 10 fictional participants. The more one plays video games, the higher one’s level of aggression tends to be.

Indeed, many researchers have used experimental designs to explore the causal effects of video game playing. They have found both positive effects, such as improved spatial skills following action games (Feng, Spence, & Pratt, 2007), and negative effects, such as increased hostility after playing violent games with lots of blood (Figure 1-3) (Bartlett, Harris, & Bruey, 2008).

Between-Groups Design versus Within-Groups Design

Experimenters can create meaningful comparison groups in several ways. However, most studies have either a between-

With a between-

groups research design , participants experience one and only one level of the independent variable.

A between-groups research design is an experiment in which participants experience one and only one level of the independent variable. In some between-

With a within-

groups research design , all participants in the study experience the different levels of the independent variable; also called a repeated-measures design .

A within-groups research design is an experiment in which all participants in the study experience the different levels of the independent variable. An experiment that compares the same group of people before and after they experience a level of an independent variable, such as video game playing, is an example of a within-

Many applied questions in the behavioral sciences are best studied using a within-

Correlational Research

Often, a researcher cannot conduct an experiment because it is unethical or impractical to randomly assign participants to conditions. Snow’s cholera research, for example, did not use random assignment; he could not randomly assign some people to drink water from the Broad Street well. His research design was correlational, not experimental.

In correlational studies, we do not manipulate either variable. We merely assess the two variables as they exist. For example, it would be difficult to randomly assign people to either play or not play video games over several years. However, we could observe people over time to see the effects of their actual video game usage. Möller and Krahé (2009) studied German teenagers over a period of 30 months and found that the amount of video game playing when the study started was related to aggression 30 months later. Although these researchers found that video game playing and aggression are related (as shown in Figure 1-3), they do not have evidence that playing video games causes aggression. As we will discuss in Chapter 13, there are always alternative explanations in a correlational study; don’t be too eager to infer causality just because two variables are correlated.

CHECK YOUR LEARNING

| Reviewing the Concepts |

|

|

| Clarifying the Concepts | 1- |

How do the two types of research discussed in this chapter— |

| 1- |

How does random assignment help to address confounding variables? | |

| Calculating the Statistics | 1- |

College admissions offices use several methods, including standardized test scores (such as those from the SAT in the United States), to operationalize the academic performance of high school students applying to college. Can you think of other ways to operationalize this variable? |

| Applying the Concepts | 1- |

Expectations matter. Researchers examined how expectations based on stereotypes influence women’s math performance (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999). Some women were told that a gender difference was found on a certain math test and that women tended to receive lower scores than men did. Other women were told that no gender differences were evident on the test. Women in the first group performed more poorly than men did, on average, whereas women in the second group did not.

|

Solutions to these Check Your Learning questions can be found in Appendix D.